How strong is an Indian case for getting back the Kohinoor diamond from Britain? It depends on whether one considers this in terms of law, politics, history or morality. The issue is not as simple as it appears and the complexities have only been magnified by the Supreme Court's quixotic decision to entertain a petition that asks whether the government is bringing home the Kohinoor.

The word "home" is itself a decidedly contentious question here. The Kohinoor is believed to have originated in the mines of Golconda, its original home. In subsequent centuries, it adorned the Mughal court. Next it was grabbed by Nadir Shah, the Persian plunderer, when he ransacked Delhi in 1739. Subsequently, it went into the hands of Ahmed Shah Abdali, villain to generations of Indians, and Father of the Nation to generations of Afghans.

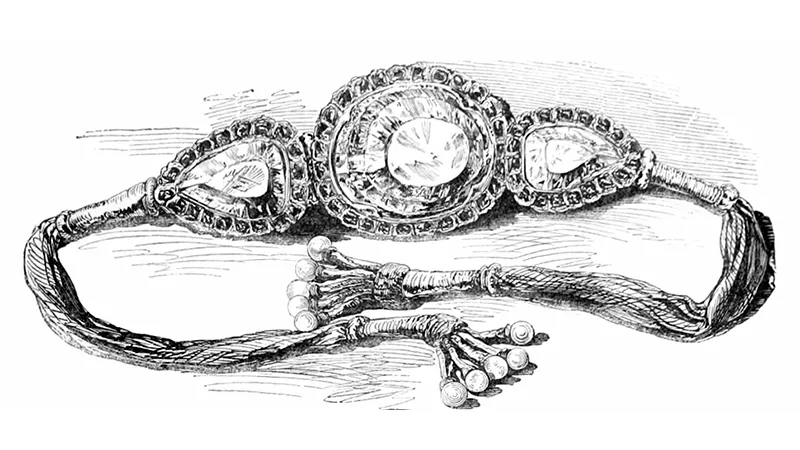

Abdali's descendant, Shah Shuja, was forced to surrender it to Ranjit Singh in the early 19th century. The Afghan had taken refuge in Lahore and bowed to the rising power, the Sikh Empire. Ranjit Singh died in 1839. In the following decade, the Sikhs fought two compelling wars with the East India Company army. The Second Anglo–Sikh War ended in 1849 with defeat for Duleep Singh, the minor son of Ranjit Singh and the then Maharaja in Lahore.

At this point, the victors, the British, forced the minor king to sign the Treaty of Lahore and surrender his kingdom and treasury. Thus Punjab was annexed by the British and the Kohinoor, as part of the treasury, was given to the British. The Company subsequently presented the diamond to Queen Victoria.

What is the legal status of this transaction? It was a treaty (or an instrument of surrender, if you prefer) negotiated between the Sikh Empire, a state represented by the boy–emperor and his advisors, and the East India Company, performing a quasi–state role. The East India Company was a private corporation, the Indian territories of which were recognised as falling under the sovereignty of the British Crown as per the Charter Act of 1813, passed by the British Parliament.

This is the legal position. Obviously, as Indians and as human beings, our sympathies will lie with the innocent Duleep Singh, a young boy, barely 10, deprived of his kingdom by a conquering alien power and soon to become one of the tragic figures of history. Nevertheless, when he signed away his kingdom and his treasures and his precious diamond, the fact is he was within his rights to do so. Just as, one may add, Shah Shuja was within his rights to give away the Kohinoor. Of course, neither did it willingly, but that is a different question from whether they had the right to do it.

As such, the Kohinoor diamond was neither "stolen" nor "gifted". Its transfer to the British could perhaps be termed war reparations, unfairly imposed on the loser, but legally validated by a treaty nevertheless. If a petition is heard in the Supreme Court on such a matter, do consider the theoretical possibility of an Afghan organisation moving a petition in the Lahore High Court, asking the Pakistan government to secure the Kohinoor, in its capacity as current sovereign of Lahore, to return it to the government in Kabul. Sounds ridiculous, doesn't it? It does, because history is not always justifiable in a contemporary legal battle.

It is true that other Indian artefacts have been returned to India by foreign governments. As has been pointed out by the Narendra Modi government, in the past two years, antique sculptures have been restored to India from Australia, Germany and Canada, in each case after intervention at the Prime Ministerial level. Are these precedents for the Kohinoor?

There are two points here. If an artefact is proven to have been stolen by the antique smuggling industry, a case for its return by the government in the jurisdiction of which the antique has been found is easy to make. Otherwise, it comes down to a political gesture from the other government, which may decide it is morally obligated to giving back an item that was historically acquired (perhaps by war) but not stolen by a non–state actor in recent times.

As such, the Kohinoor can be returned to India (or given to India, since the word "return" will see the Pakistani government filing a counter–petition) if the British government so decides. A legal case against historical war booty is very difficult to sustain. It also leads to three tantalising questions:

(1) The Kohinoor was part of war booty that is now in the control of the British government. Much of Indian war booty is in the private homes of descendants of servants of the Company and the Raj in Britain. Is a quest then for return going to stop at just the Kohinoor? How does one explain that to a court of law?

(2) Years ago, this writer visited the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul. Among the first artefacts he saw at the museum was an "Indian throne" given to the Ottomans as a gift by Nadir Shah of Persia. If a case can be filed against the British government, why are we sparing the Turkish and Iranian governments and many others too?

(3) While the Supreme Court may believe that "this country has never colonised other nations" and while Indian military expeditions were nowhere as ferocious and rapacious as those of European powers of the past three or four centuries, the fact is that India too is home to artefacts of other countries. What does it do with them?

The Central Asian section of the Indian Museum in Delhi was built using hundreds of pieces liberally picked up, pulled out of walls and determinedly removed by Sir Aurel Stein, the British–Hungarian archaeologist, during his visits to Chinese Turkestan, now the province of Xinjiang. Peter Hopkirk's Foreign Devils on the Silk Road has an elaborate description of the efforts of Stein and his peers.

Should the Indian government really get down to returning these artefacts to China? It would be better to let history, including the Kohinoor, be as it is.

This commentary originally appeared in NDTV.com.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV