Introduction

A truly representative democracy seeks adequate representation of women in politics.[1] Though representative governments have increased across the world in the last few decades, the participation of women has remained low. According to UN Women, as of September 2022, there were 30 women serving as elected heads of state and/or of government in 28 countries (out of a total of 193 UN member states).[2] This is despite concerted multi-prolonged efforts in recent times to promote women’s empowerment and improve gender equality.

Legislative representation is fundamental to political empowerment, enabling participation in the law-making process. Legislatures play a vital role in raising debates and discussions on various aspects of governance and in exacting accountability from the government. Women’s representation in the national parliament is a key indicator of the extent of gender equality in parliamentary politics. India is the largest and one of the most resilient parliamentary democracies in the world with a female population of 662.9 million.[3] This makes India an important case study of parliamentary representation of women. This paper looks at how women’s representation in India’s Parliament has improved since independence, if at all.

The paper opens by underlining the imperative of gender equality in political representation and outlining the international and national constitutional and legal obligations to achieve it. It then discusses the change in women’s representation in India’s Parliament since Independence and compares it to their share of seats in state legislatures and local self-government bodies. It notes the dichotomy between the rapid increase of women’s participation as voters in elections and other political activities, and the slow rise of female representation in Parliament. The third section examines the intersections in institutional and socio-cultural factors that impede greater women’s representation in Parliament. The paper closes with an outline of certain institutional reforms that could improve the representation of women in parliamentary politics

I. The Imperative for Representation

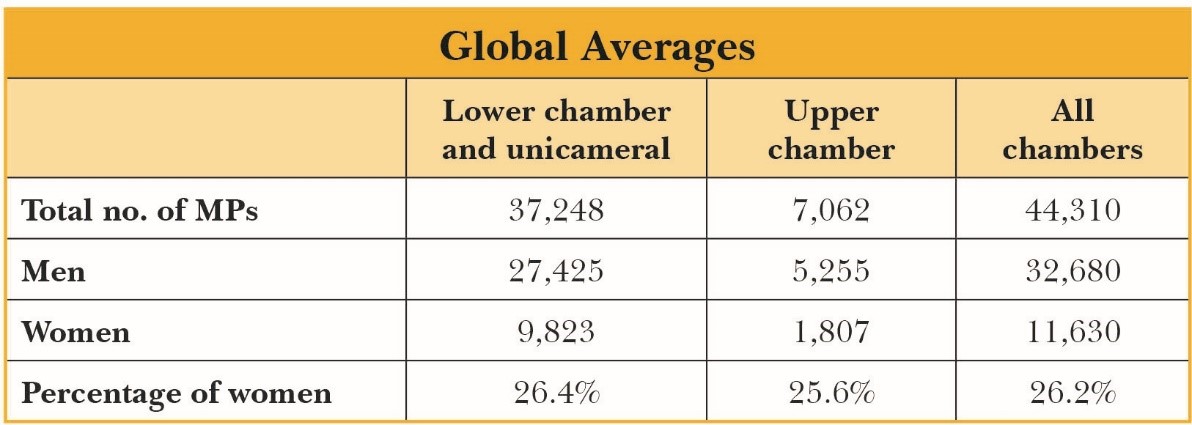

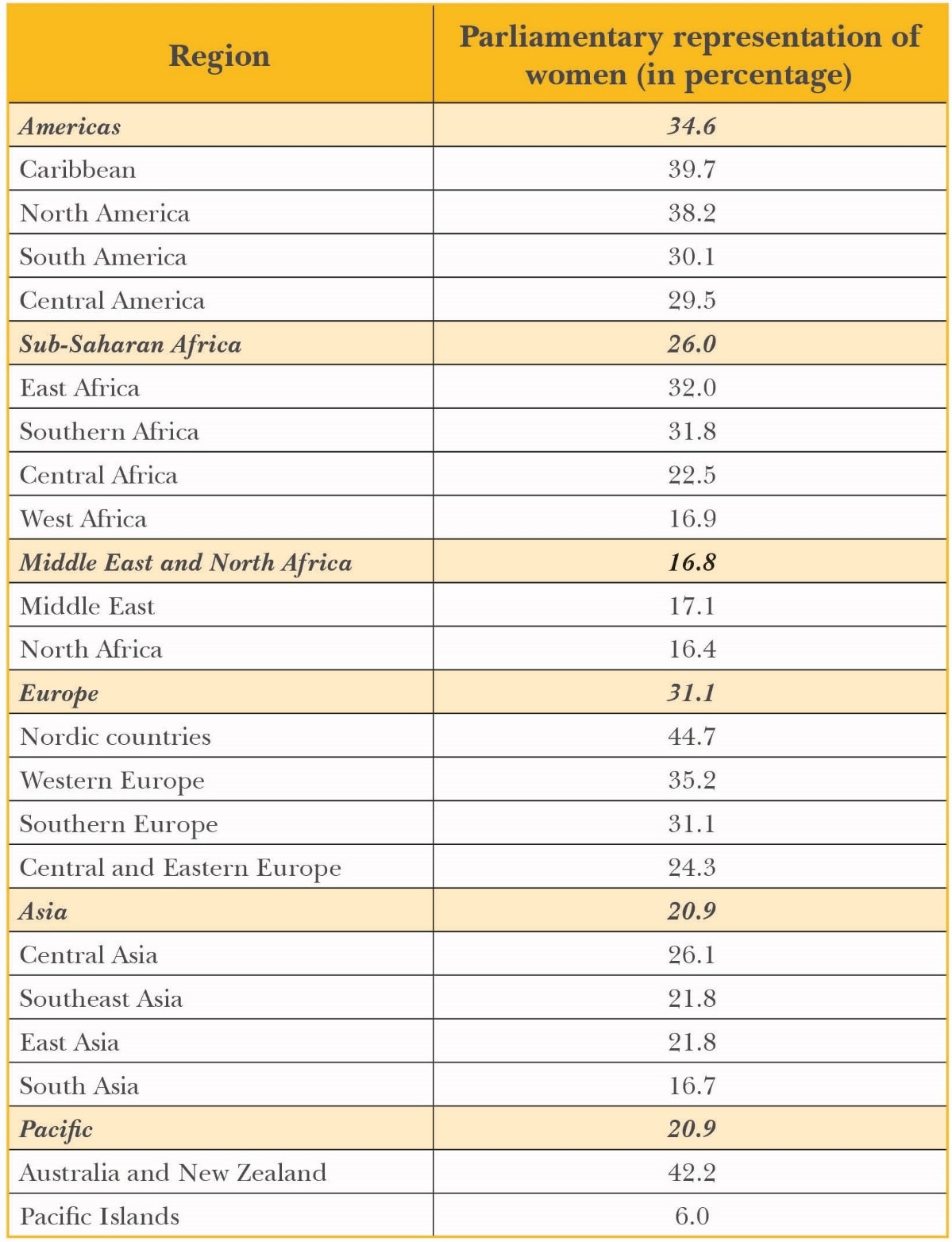

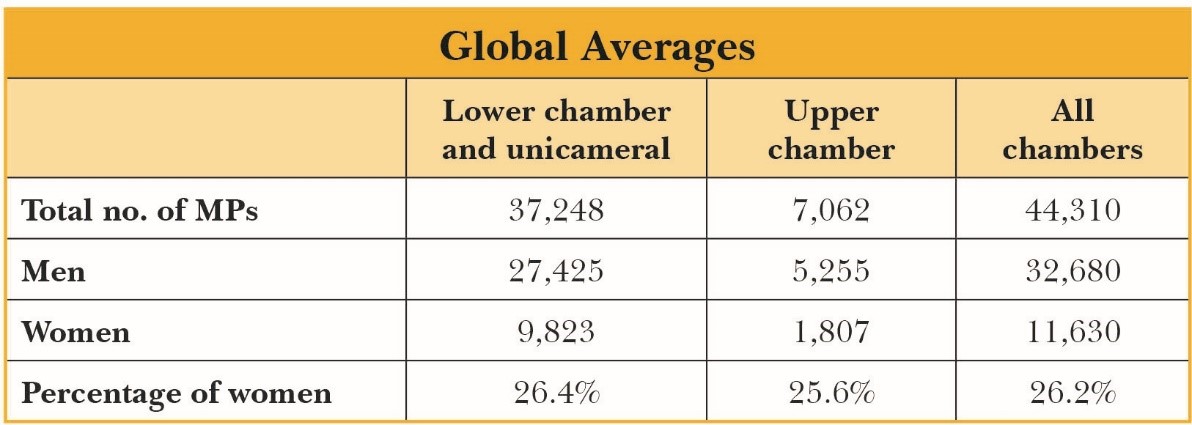

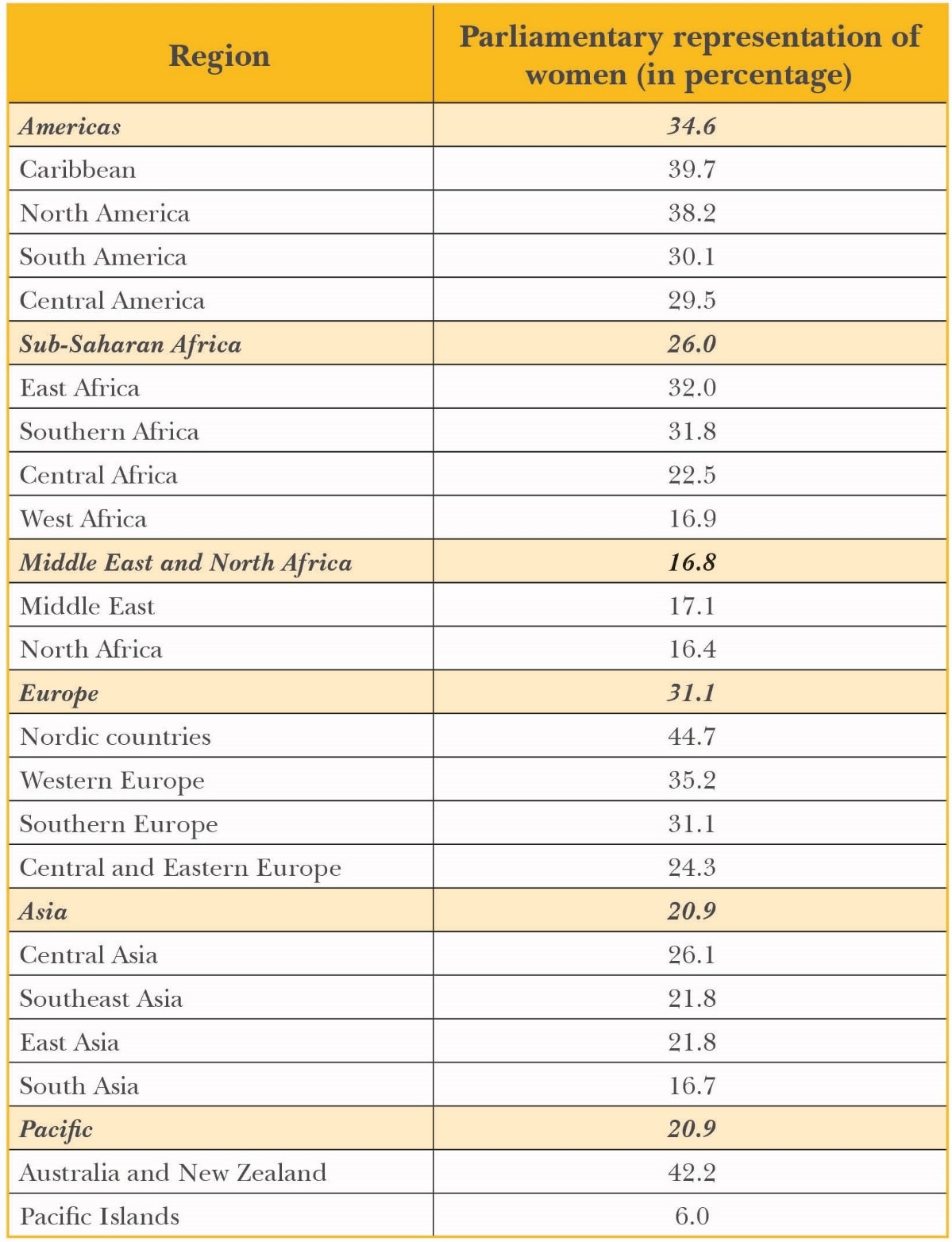

As of May 2022, the global average of female representation in national parliaments was 26.2 percent (see Table 1). The Americas, Europe, and Sub-Saharan Africa have women’s representation above the global average; and Asia, the Pacific region, and the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) region, are below average[4] (see Table 2).

Women’s representation within Asia also varies, with the South Asian countries faring worse than the others (see Table 2). IPU data of May 2022 showed that women’s representation[a] in Nepal, for example, was 34 percent, in Bangladesh 21 percent, in Pakistan 20 percent, in Bhutan 17 percent and in Sri Lanka 5 percent.[5] For India, women’s representation in the Lok Sabha (the Lower House)[b] has remained slightly below 15 percent. The study does not include Afghanistan, but World Bank data of 2021 stated that female representation in the country’s last parliament was 27 percent.[c],[6]

Table 1: Global Average of Women’s Representation in Parliament

Source: IPU Parline: Global Data on National Parliament (as of May 2022)

Table 2: Women’s Representation in Parliament, By Geographical Region

Source: IPU Parline: Global Data on National Parliament (as of May 2022)

Historical Gender Inequality in Politics

Proportionate political representation of all populations is a fundamental ethos of modern constitutional democracy. Women, who constitute almost one-half of the world’s population[7] (49.58 percent), have historically been politically marginalised in both developed and developing nations. From the mid-19th century onwards, however, social movements have succeeded in effecting widespread reforms. The charter of the United Nations Organization (UNO, started in 1945) supported women’s rights. Buttressed by the feminist movements of the 1960s and ‘70s, the UN General Assembly in 1979 adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), often considered as an International Bill of Rights for women. In the Convention, Article 7 upholds women’s right to hold political and public office.

Years later, in 2000, UN member states adopted the Millennium Declaration and outlined eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), to be achieved by 2015, which included promoting gender equality. In January 2016 the initiative was extended to pursue 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of which Goal 5 seeks to “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”, ensuring “women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life.”[8]

Political scientists have expounded on the benefits of increased participation of women in representative institutions. Anne Phillips (2017) has noted that “women bring different skills to politics and provide role models for future generations;”[9] they “appeal to justice between sexes;” and their inclusion in politics facilitates representation of the specific interests of women in state policy[10] and creates conditions for a “a revitalised democracy that bridges the gap between representation and participation.”[11] Many years earlier, Hannah Pitkin (1967) had discussed two forms of political representation— ‘descriptive’ and ‘substantive’, where ‘descriptive’ entails ‘accurate’ representation of all communities forming part of the polity, and ‘substantive’ refers to tangible policy outcomes from such representation. Emanuela Lombardo and Petra Meier (2014) have argued that there is a third form of representation—i.e., ‘symbolic’, which constitutes not only the “visual dimension, expressed through symbols, but also a discursive dimension found in metaphors and stereotypes often expressed in policy discourses.”[12] A combination of all three dimensions of political representation is crucial to ensure democratic participation and transformation, most importantly by, and for, women.

II. Women’s Political Participation in India

India has a history of marginalisation and exploitation of women framed by patriarchal social structures and mindsets. Beginning in the 19th century, social reform movements succeeded in pushing for women’s well-being and empowerment. The Indian freedom movement, starting with the swadeshi in Bengal (1905-08) also witnessed the impressive participation of women,[13] who organised political demonstrations and mobilised resources, as well as occupied leadership positions in those movements.[14]

After India attained independence, its Constitution guaranteed equal status for men and women in all political, social and economic spheres. Part III of the Constitution guarantees the fundamental rights of men and women.[d] The Directive Principles of State Policy ensure economic empowerment by providing for equal pay for equal work by both men and women, humane conditions of work, and maternity relief. Any Indian citizen who is registered as a voter and is over 25, can contest elections to the lower house of Parliament (Lok Sabha) or the state legislative assemblies; for the upper house (Rajya Sabha) the minimum age is 30.[15] Articles 325 and 326 of the Constitution guarantee political equality and the right to vote.[16]

There are constitutional provisions for reservation of seats for the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes in Parliament and in legislative assemblies. A proposal to provide a similar reserved quota for women was discarded at the time of drafting the Constitution. It was opposed by leading Indian women’s associations[17] and by the ruling party, the Congress, who were of the view that women should be able to get elected on an equal footing as men.[18] Later, in 1974, the report of the Committee on the Status of Women in India argued for greater representation of women in political institutions and again brought the issue of reservation of seats for women to the fore.[19]

Subsequently, in 1992, the 73rd and 74th amendments to the Constitution provided for reservation of one-third of the total number of seats for women in Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) and municipal bodies. The amendment intended to improve women’s participation in decision-making at the grassroots.[20] Proposals to legislate the reservation of seats for women in parliament and state assemblies first emerged in 1997, but they have met with much opposition, and no such law has yet been passed.[21]

At the same time, India has taken a number of steps towards women’s empowerment in other domains, such as marriage and employment. For example, the Supreme Court has conferred daughters the equal status of a coparcener in Hindu families, providing them inheritance rights. It has also ruled that “women officers in the army should be entitled to permanent commission and command postings in all services other than combat, and they have to be considered for it irrespective of their service length.”[22] Recently, the minimum age of marriage for girls was raised from 18 to 21 years.[23]

Taking Stock of Progress

There are three main parameters to assess the state of women’s participation in politics in India: how many of them vote; how many of them contest elections; and how many of them get elected to legislative bodies at the national, state and local levels. A fourth parameter is the participation of women in election-related and other political activities as party workers and supporters.

Women as Voters

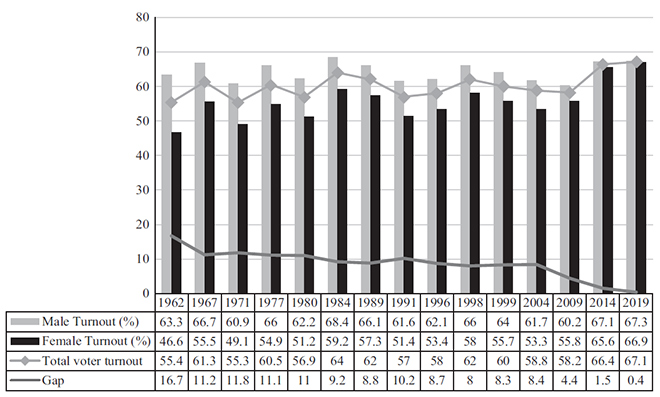

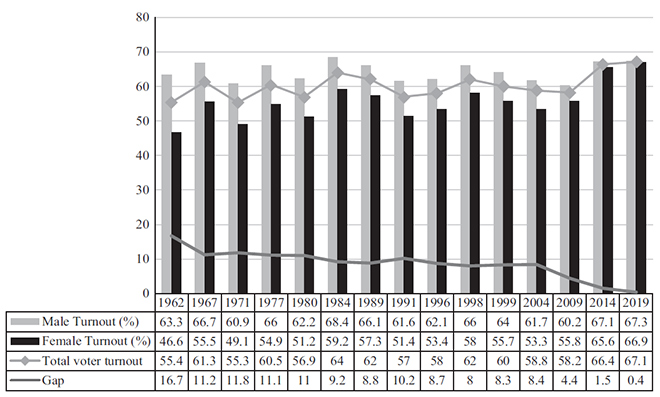

Following Independence, women’s participation as voters was not immediately enthusiastic. It increased gradually, however; in the last Lok Sabha election of 2019, almost as many women voted as men—a watershed in India’s progress towards gender equality in politics which has been called a “silent revolution of self-empowerment”[24] (see Figure 1). The increased participation, especially since the 1990s, is attributed to a number of factors.

First, higher levels of literacy among women and their greater participation in the workforce have contributed to increasing their political awareness and confidence to cast their vote.[25] Second, the growth of the electronic media and the digital revolution have expanded the reach of awareness campaigns about voting rights, conducted both by Election Commission of India and other organisations. Third, the Election Commission has adopted institutional measures to encourage women to vote, such as ensuring safety by guarding against intimidation, and providing separate queues for women at polling booths. Women-friendly ‘pink booths’ are set up where the entire staff including election officials, police and security personnel, are female.[26] With heightened security measures during elections over the years, violence and intimidation of voters on polling day has largely declined, encouraging more people to participate, and not only the women.[27] Fourth, reservations for women in panchayats and municipalities have also helped enhance female inclusion in the structures of power at the local level.[28] Fifth, political reforms, technological transformation, and notions of women’s rights are gaining momentum and encouraging more women to vote.[29]

Figure 1: Voter Turnout in Lok Sabha Elections: 1962-2019 (%)

Source: Sanjay Kumar (eds.) Women Voters in Indian Elections: Changing Trends and Emerging Patterns, Routledge, 2022, 20. (Data Source: Election Commission of India)

Women as Candidates

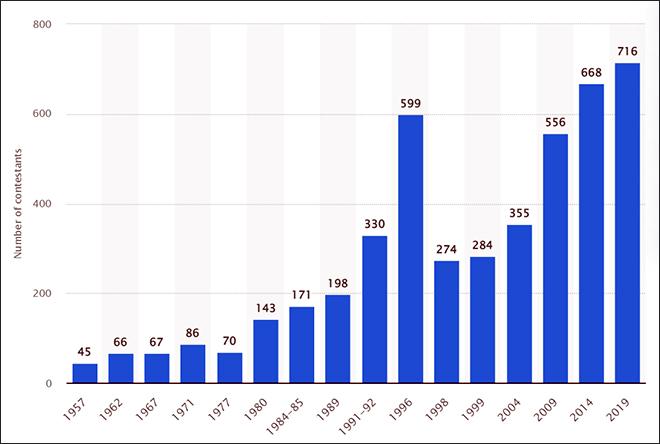

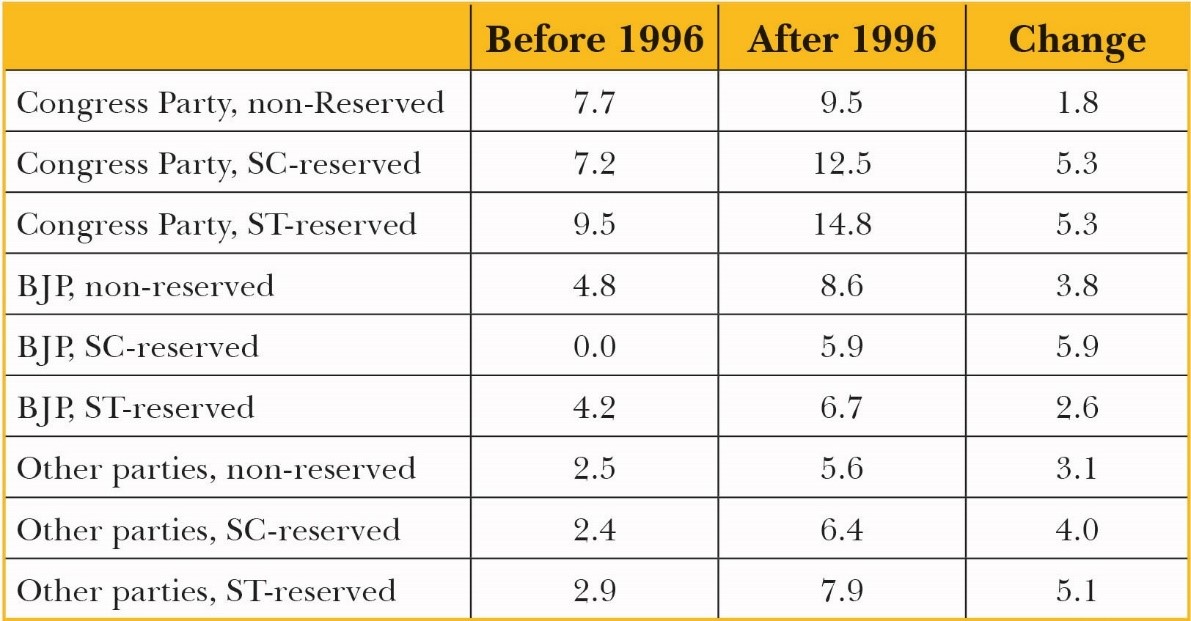

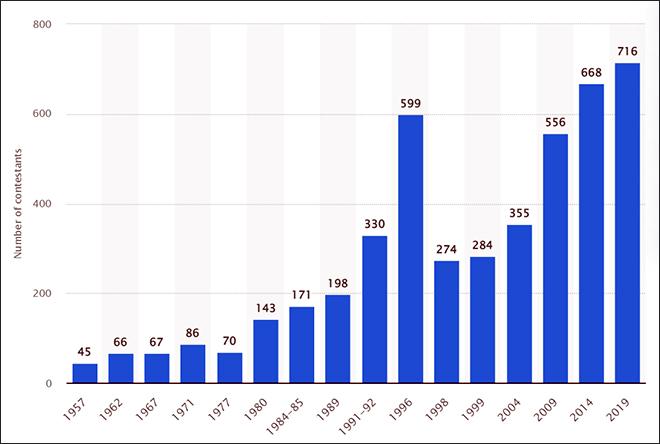

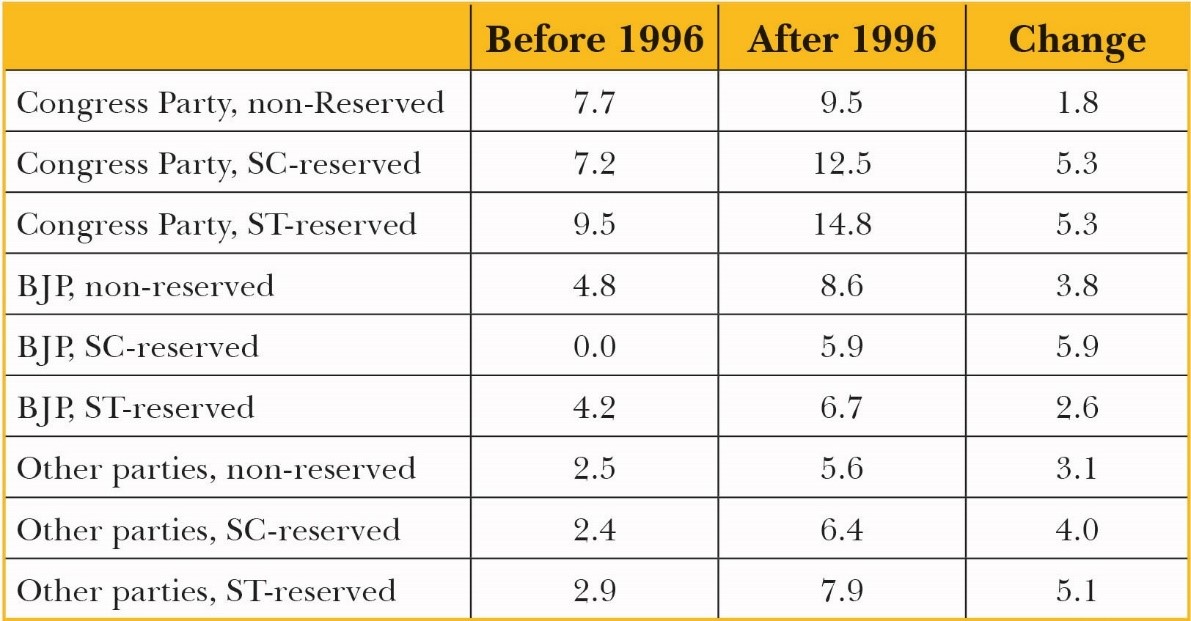

The number of women candidates fielded by major political parties in both the parliamentary and state assembly elections remained fairly low till the early 1990s, before rising in the mid-1990s[30] (see Figure 2). Political scientist Francesca R. Jensenius has argued that reservations for women at the local level beginning in 1992 increased their representation in those seats. The proposal to also reserve seats for women in Parliament and the state assemblies was introduced after the 1996 general elections. Francesca’s study noted that after 1996, all the major political parties have nominated many more women candidates than before (see Table 3).

Women in India run in two types of constituencies.[31] First, as argued in a paper by economists Mudit Kapoor and Shamika Ravi, women candidates are more likely to contest in constituencies that have a relatively higher proportion of men.[32] Second, Francesca’s study revealed, women tend to contest more for seats reserved for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes.[33] A possible explanation for the first pattern could be that women prefer to contest in constituencies where their numbers are lower because winning such seats will be crucial in making themselves heard.[34] A reason for the second phenomenon could be the increasing pressure on parties to nominate more women candidates. Parties find it easier to remove male incumbents from reserved seats and replace them with women as the male politicians from the SC and ST communities are perceived to be more “dispensable than other male incumbents.”[35]

Overall, however, while women candidates in parliamentary elections have increased over time (Figure 2), their proportion compared to male candidates remains low. In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, of the total of 8,049 candidates in the fray, less than 9 percent were women.[36]

Figure 2: Number of Women Candidates in the Lok Sabha Elections (1957-2019)

Table 3: Female Candidates in General Seats and Reserved Seats, Before and After 1996 (%)

Source: Francesca R Jensenius, “Competing Inequalities? On the Intersection of Gender and Ethnicity in Candidate Nominations in Indian Elections”, Government and Opposition , Volume 51 , Issue 3: Candidate Selection: Parties and Legislatures in a New Era , July 2016 , pp. 440 – 463

Women’s Representation in Parliament

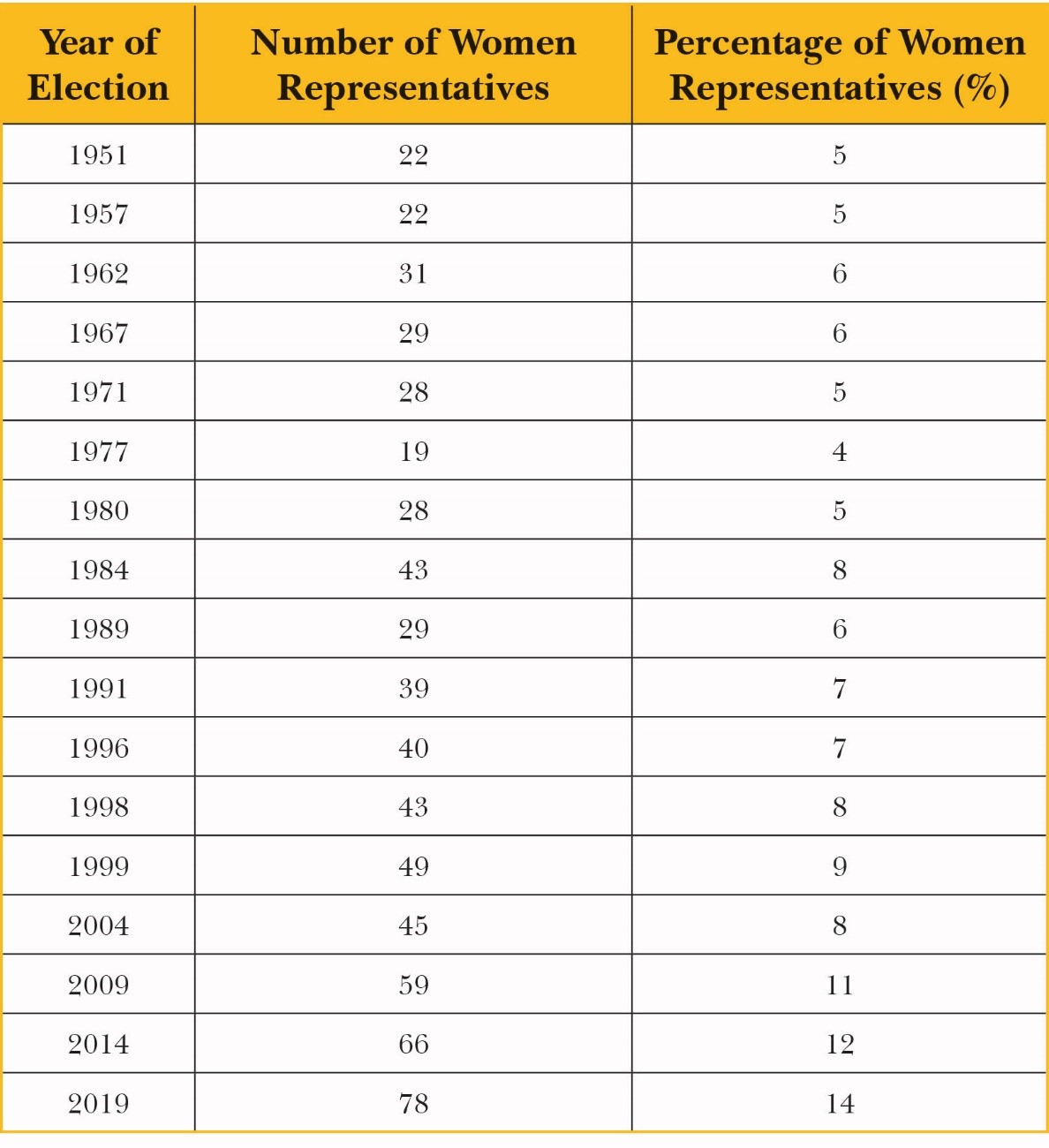

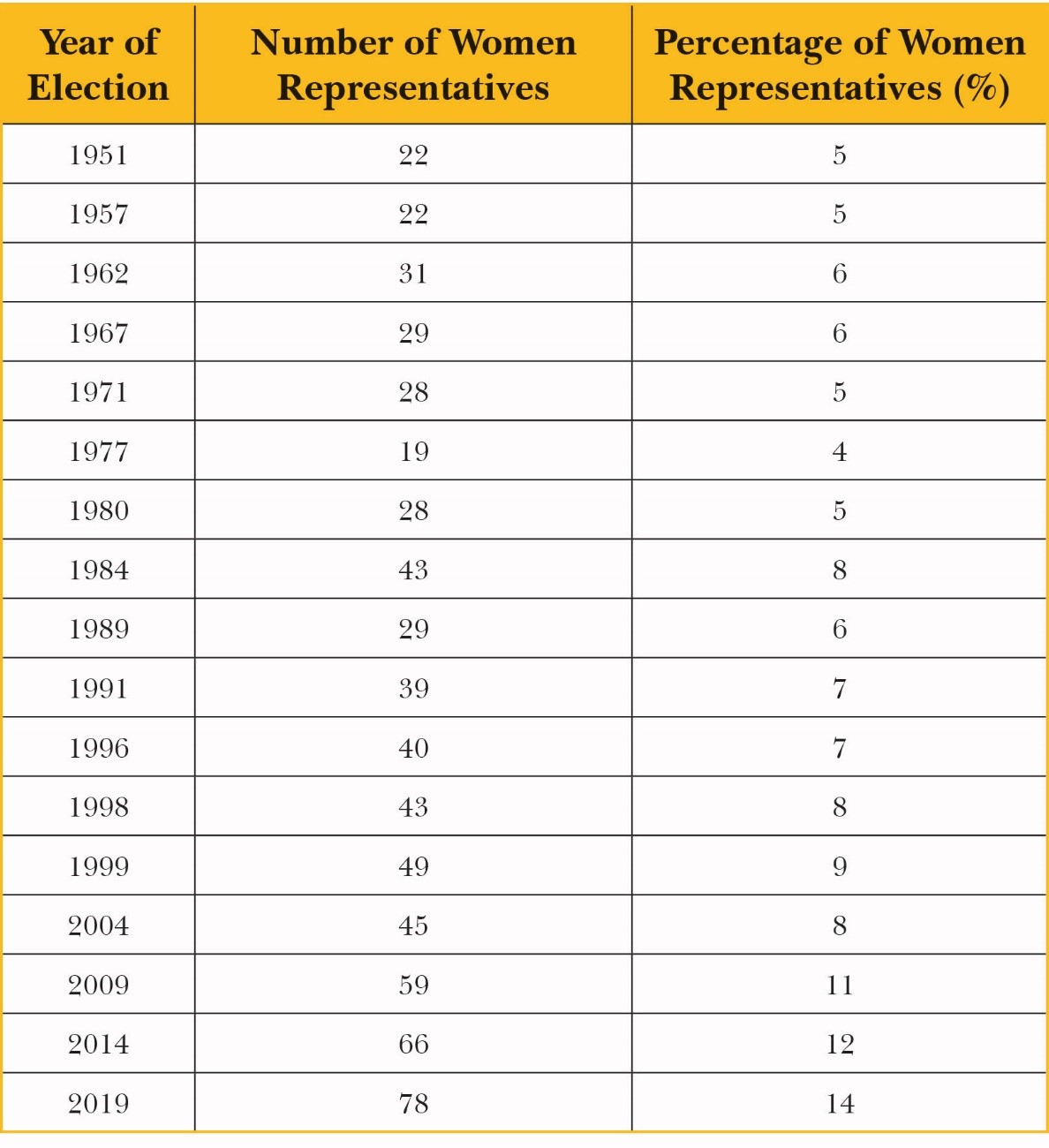

Parliaments and state legislatures “not only make laws and hold the executive accountable but also make a ‘representative claim’[37] to represent different constituencies, identity groups, and interests.”[38] In parliamentary democracies like India, membership to Parliament is also a prerequisite for participating in the government as a minister. Although women’s participation as voters in elections has increased significantly, the data on women’s representation in both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha suggests that the proportion of women representatives has remained low in comparison to their male counterparts (see Tables 4 and 5). The highest proportion of women representatives elected to the Lok Sabha so far was in the 2019 elections, and it was less than 15 percent of total membership.

The number of women candidates and MPs varies greatly across states and parties. In the present Lok Sabha (17th), Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal have the highest numbers of women MPs. In terms of proportion, 14 percent of total Lok Sabha MPs in UP are women, and the share is 26 percent in Bengal.[39] As for political parties, Congress fielded 54 women candidates in 2019 (12.9 percent of all candidates it fielded that year); and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) fielded 53 women (12.6 percent).[40],[41] Overall, the states of UP, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal and Bihar saw a considerable number of women being fielded that year.[42] In terms of percentage, Goa and Manipur had fielded the highest proportion of women candidates, which is 17 percent of total candidates in each of the two states.[43] In the same year, parties like the Biju Janata Dal (BJD) in Odisha and the TMC in West Bengal fielded more women in the Lok Sabha polls: BJD nominated 33 percent of women candidates in Odisha,[44] and TMC, 41 percent in Bengal.[45]

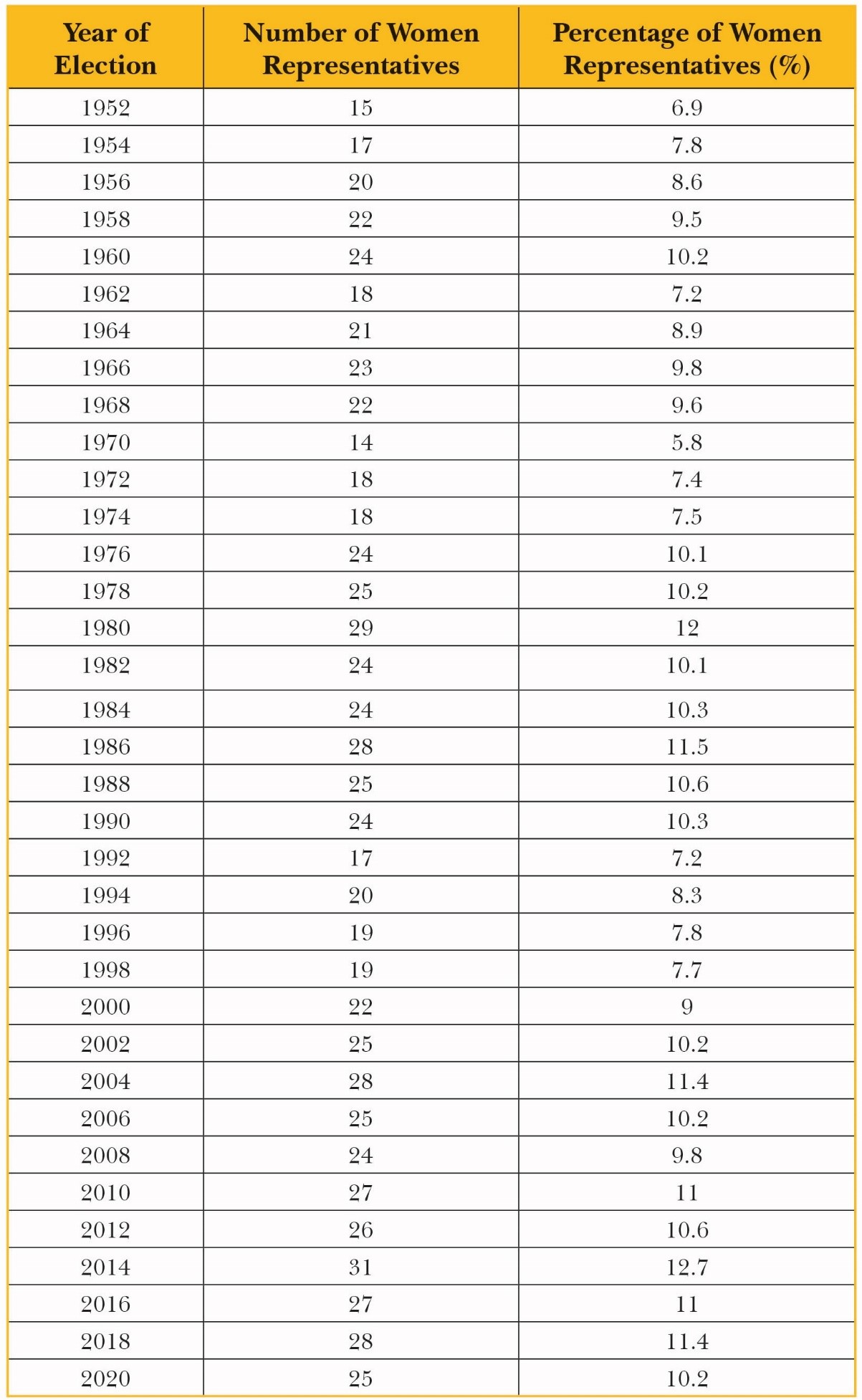

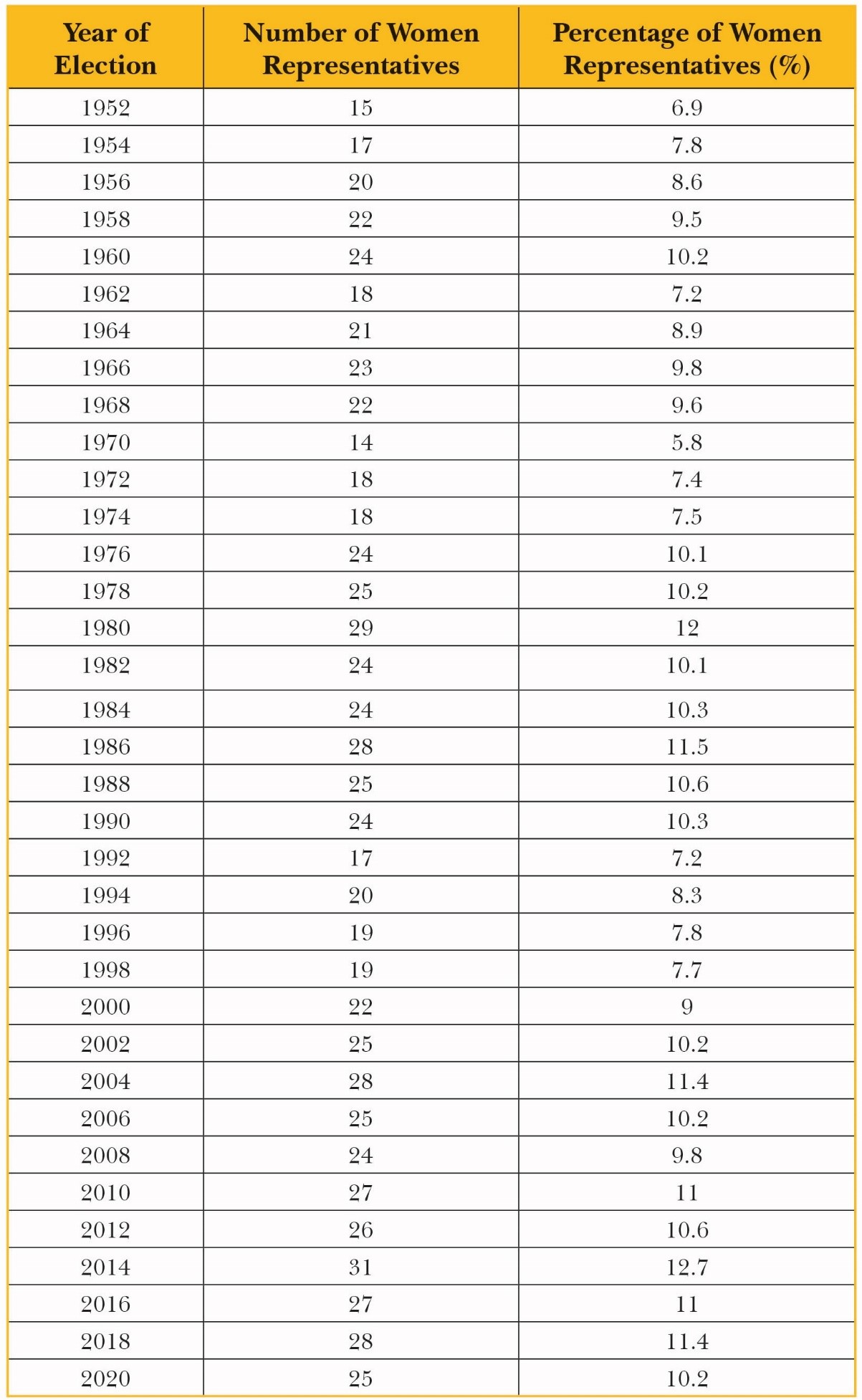

Women’s representation in the Rajya Sabha has been slightly lower than in the Lok Sabha, not yet crossing 13 percent of the total membership of the house according to 2020 data. In state legislative assemblies or Vidhan Sabhas, meanwhile, average representation is even lower, mostly below 10 percent.[46]

Table 4: Women’s Representation in the Lok Sabha

Source: Election Commission of India

Table 5: Women’s Representation in the Rajya Sabha

Source: Election Commission of India

Women as Political Workers

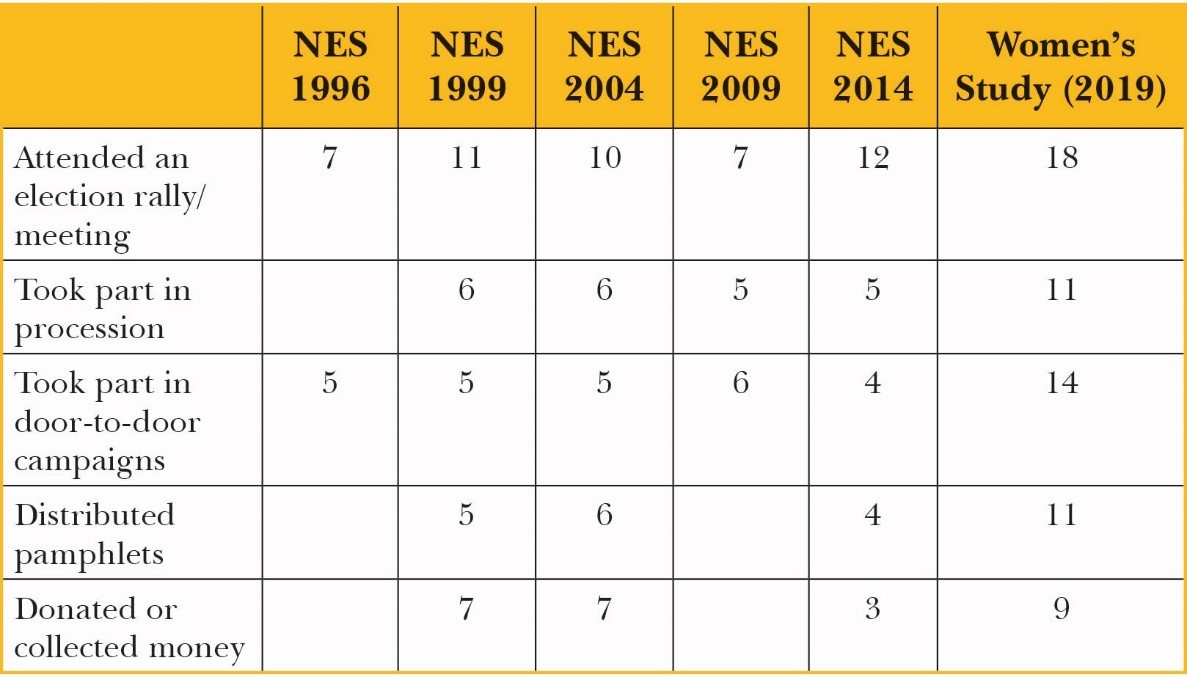

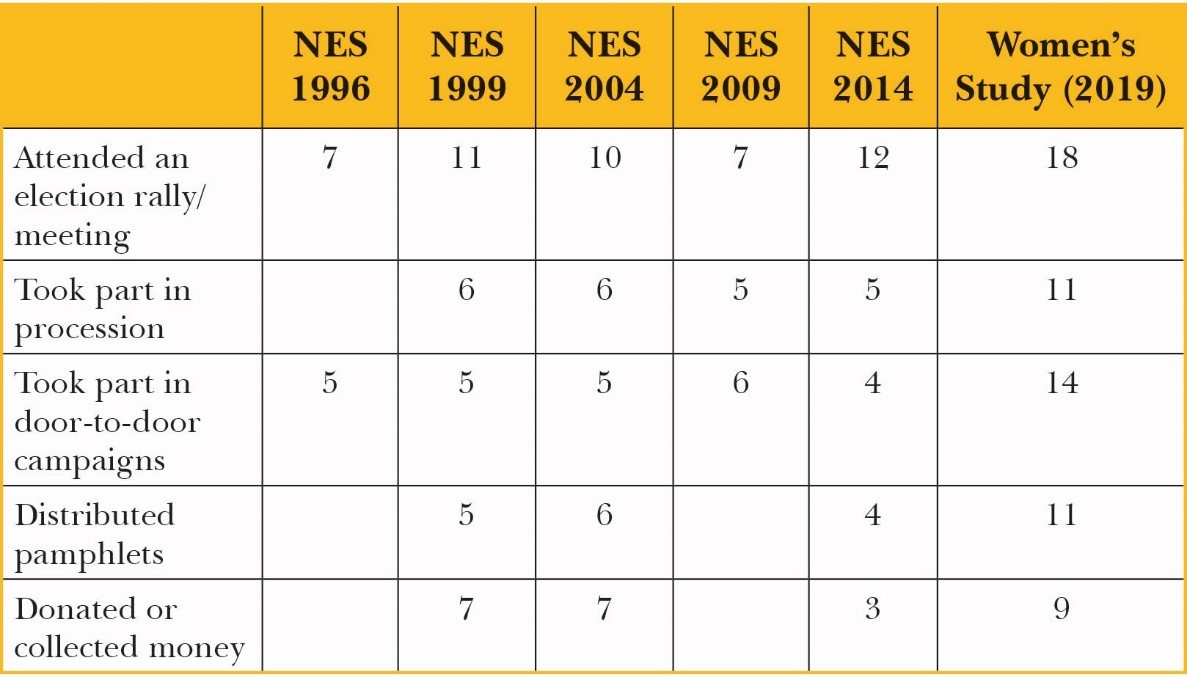

Surveys by the Centre for Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) show that women’s participation in political activities—such as joining election rallies, conducting door-to-door campaigns, distributing election pamphlets, and collecting election funds—has increased in the last three decades (see Table 6). However, such participation remains low, overall. This suggests that higher levels of education, political awareness, and exposure to public life has led to greater political mobilisation of women as voters, but various institutional and structural challenges continue to deter them from fully participating in the many other aspects of electoral politics.

Table 6: Women’s Participation in Political Activities: 1996-2019 (%)

Note: This table is based on responses in the surveys conducted by CSDS from 1996-2019. For purposes of comparison, the study extracted the data linked to women respondents and looked at their engagement in electoral activities.

Source: Sanjay Kumar (eds.) Women Voters in Indian Elections: Changing Trends and Emerging Patterns, Routledge, 2022

Successes in Women’s Participation in Local Politics

India has a third tier of government at the local level in the form of municipalities or municipal corporations in cities and towns as well as PRIs in rural areas. The 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments were introduced in 1992 to provide “new opportunities for local level planning, effective implementation and monitoring of various social and economic development programmes in the country.”[47] One of the most important and transformational aspects of these amendments was their provision of reservation of one-third of the total seats of local body elections for women.[48] Studies have shown that the policy led to a phenomenal rise in the political participation of women at the local level.[49] Since then, 20 of India’s 28 states[e] have raised[50] the reservation to 50 percent.[51]

The challenge of ‘proxy representation’ has also declined—where women elected to office were being largely “controlled” by their male family members.[52] A large number of skills development programmes and leadership training sessions for women at the grassroots, conducted by both government and non-government organisations (NGOs), have helped improve the performance of elected women political leaders.[53]

III. Challenges in Women’s Representation in National and State Legislatures

Once reserved seats were constitutionally mandated for women, they participated more in representative politics at the local level. Why then has female representation in Parliament and state legislatures remained low? The reasons are many and correlated, and their intersections need to be studied properly.[54],[55] Societal prejudices, a male-dominated political party structure, family obligations, resource scarcity, and various structural hindrances[56] all impede greater participation among women as contestants and winners in parliamentary or state assembly elections.[57]

Inaccessibility of Institutions

Political parties remain the fundamental political vehicle through which parliamentary and state legislative elections in India are fought and won,[58] and the electoral prospects of independent candidates remain weak.[59] Getting a party ticket to contest a suitable parliamentary seat remains the key prerequisite for all aspiring candidates. Ticket distribution is mostly a centralised process[60] in political parties in India, although this is not unique to the country.[61] Election records show that most political parties, though pledging in their constitutions to provide adequate representation to women,[62] in practice give far too few party tickets to women candidates.[63] To be sure, the performance is uneven, and some parties fare better than others.[64]

A study by political scientist Kanchan Chandra found that a large section of women who do get party tickets and win parliamentary seats have family political connections, or are ‘dynastic’ politicians. With normal routes of accessibility limited, such connections are often an entry point for women.[65] An analysis has shown that 41 percent of all women candidates in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections were ‘dynasts’, and 30 percent of those elected were.[66]

It is still widely held in political circles that women candidates are less likely to win elections than men,[67] which leads to political parties giving them fewer tickets. Even the women from political dynasties are more likely to be given ‘safe’ seats—those previously occupied by a male family member—where their win is mostly assured.[68] Recent data, however, belies this notion: certain election results show that women candidates have equal, if not higher chances of winning in comparison to male candidates.[69]

In their paper, Thushyanthan Baskaran et al. have shown that women legislators perform better in their constituencies on economic indicators than their male counterparts. The same study found that women legislators “are less likely to be criminal and corrupt, more efficacious, and less vulnerable to political opportunism.”[70] And yet, some successful women politicians have lamented being an ‘ineffective minority’ within their parties, unable to facilitate gender inclusiveness.[71] The male-dominated party structures in India are vitiated by patriarchal mindsets that make it difficult for women politicians to obtain party nominations to fight parliamentary elections.

Non-congenial Structural Conditions

Contesting and winning parliamentary and state elections also remains difficult for women owing to several inherent structural disadvantages. Election campaigns in India are extremely demanding and time-consuming. Women politicians, with family commitments and the responsibilities of child care, often find it difficult to fully participate. Indeed, studies reveal that a supportive family is central to women leaders’ capacity to engage in a full-fledged political career.[72] The political arena in India is also a rough terrain that is marred by calumny, violence, and mudslinging. Women politicians have been constantly subjected to humiliation, inappropriate comments, abuse and threats of abuse, making participation and contesting elections extremely challenging.[73] Financing is also an obstacle as many women are financially dependent on their families. Fighting parliamentary elections can be extremely expensive, and massive financial resources are required to be able to put up a formidable contest. Absent adequate support from their parties, women candidates are compelled to arrange for their own campaign financing—this is a huge challenge that deters their participation.[74]

There is also the threat of criminalised politics, where the role of muscle power becomes paramount.[75] Women are therefore more likely to contest reserved seats which are known to be less competitive and hence less under the sway of money and muscle power.[76] Lastly, as women themselves can be influenced by patriarchal societal norms—a phenomenon known as ‘internalised patriarchy’—many women consider it their duty to prioritise family and household over political ambitions. Thus, both structural inequalities and resilient patriarchal mindsets deter women from perceiving themselves as potentially active, full-fledged political actors who can contest parliamentary or assembly polls.[77]

IV. The Case for Institutional Reforms

This analysis has revealed two crucial aspects of women’s participation in electoral politics in India. First, despite strong patriarchal norms, the country is seeing an increase in women’s political participation, parallel to higher levels of education and growing financial independence.[78] Second, the number of women contesting parliamentary and state legislative elections remains limited. Where constitutionally mandated reservation of seats for women has been provided at the local self-government level, women’s representation has increased and women are steadily exercising greater political agency. However, political parties—the primary vehicle of electoral politics—remain largely inaccessible for women to contest parliamentary and legislative elections even after 75 years of Indian independence.

Two institutional reforms are crucial at this juncture. First, it should be made legally obligatory for every registered political party to give one-third of the total number of party tickets it distributes at every election to women. The Representation of People Act, 1950, will have to be amended to enable this strategy. There are challenges to this aim, however. One is that it will require political consensus, which in itself is replete with structural challenges. Moreover, it is possible that reserved tickets may be disproportionately allotted to women from established political families, dominant castes, and financially affluent groups, given the highly centralised nature of ticket distribution in most political parties—this would undermine the very aim of promoting inclusive politics.

Second, if the party-level reform proves difficult, the Women’s Reservation Bill 2008—which mandated reservation of one-third of parliamentary and state assembly seats for women—will have to be revived. This also needs a consensus among the political parties. The bill was passed in the Rajya Sabha in 2010 but got stalled in the Lok Sabha after certain parties objected strongly, claiming the bill violates the equality principle and that it distorts the logic of representation.[79] There was also strong disagreement on the issue of having sub-quotas for socially and educationally backward castes within this quota for women.[80] Though all major political parties agreed to the bill on principle, no concerted effort was made to overcome the smaller differences and pass the bill into law.

Conclusion

The organic shift to opening up spaces for women in Indian parliamentary politics has been slow. Given the deep structural constraints that impede progress in women’s political participation, institutional transformation can usher in inclusive politics, albeit only to a certain degree. Another imperative is social transformation. As noted in this paper, better educational opportunities for women, their financial stability, the relative erosion of social prejudices, coupled with greater media awareness have compelled political parties to create spaces for women’s participation. With the number of women voters increasing, political parties have in recent years designed pro-women welfare policies seeking their electoral support.[81]

As the movement for women’s political emancipation gathers momentum, women’s organisations and networks within political parties and civil society must continue to help them assert their presence within the larger political and social landscape. Women’s political mobilisation can be ramped up to compel urgent institutional reform towards greater representation of women in India’s Parliament and state assemblies. More women are needed in these platforms to transform the discourse on governance and policy-making, and bring India closer to becoming a truly inclusive and representative democracy.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV