-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Debosmita Sarkar and Sunaina Kumar, “Women-centric Approaches under MUDRA Yojana: Setting G20 Priorities for the Indian Presidency,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 375, October 2022, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction: Women’s Entrepreneurship and the Indian G20 Presidency

The World Economic Forum estimates that it would take at least 268 years to close the gender gaps in economic participation and opportunities across the world.[1] The imperatives include promoting gender parity in economic participation through education, digital and financial inclusion, and legal protection, among others.[2] Incentivising structural changes to segmented labour markets is a long-term resolution. In the near term, women need to be provided a platform with equitable economic opportunities for further growth and development. Advancing women’s entrepreneurship through digital and financial inclusion can create this platform. The Global Gender Gap Report 2021 also shows that despite improvements towards skill development and wage equality—albeit slow—the lack of women in leadership positions remains persistent, limiting progress in parity.[3] Moreover, establishing a thriving ecosystem of female entrepreneurs can help other unemployed women overcome societal biases against women-led ventures.

The G20 economies are attempting initiatives that hold promise in advancing women’s entrepreneurship through financial assistance, knowledge creation, and governance for nurturing entrepreneurial conditions. The United States, for example, allocated more than US$ 100 million in 2020 for bringing innovative women-led ideas to the forefront of the business world.[4] For its part, Italy made US$ 47 million in financing available for women-led businesses in high-technology sectors.[5] Other G20 countries like Germany, Turkey and those in the European Union have embarked on awareness campaigns and supported women’s cooperatives through trainings and research to promote women’s entrepreneurship.[6] Despite such attempts, however, the G20 Ministerial Conference on Women’s Empowerment (MCWE) held in August 2022 unanimously acknowledged that persistent gender inequalities continue to restrict commercial opportunities of the MSME sector across these economies, and the rest of the world.[7]

India could show the way. The country has nearly half-a-million working-age women and 15 million women-owned micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) that directly or indirectly provide employment to almost 27 million people.[8] Identifying women as pillars of change, India has introduced a number of government schemes to support women-led enterprises. These include comprehensive schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), Pradhan Mantri MUDRA Yojana (PMMY), Startup India, and Stand-Up India—all of which together take an integrated approach to addressing the most critical constraints faced by micro enterprises, especially those led by vulnerable groups such as women and social minorities. By 2030, an estimated 30 million women-owned MSMEs are expected to flourish in India, providing employment to nearly 150 million people.[9]

The PMJDY and PMMY initiatives seek to empower women through financial inclusion. Indeed, studies have revealed that higher rates of exclusion exist among women than men in India. The PMJDY, launched in 2014, was backed by efforts from the government to help women obtain basic bank accounts. Building on the PMJDY, the PMMY was launched in 2015 to formalise microfinance lending, through the last-mile delivery of credit for the underserved, with a focus on women, and to encourage female entrepreneurship.

The two schemes have played a key role in promoting women’s economic participation in the country and will be crucial to enabling a sustainable economic recovery in the post-pandemic world. This paper analyses the impact of the Jan Dhan Yojana and the MUDRA Yojana on women’s financial inclusion in India and, thereby, the prospects for sustainable development. It highlights the priorities for the G20 in this domain.

I. Financial Inclusion, Women’s Entrepreneurship, and Inclusive Development

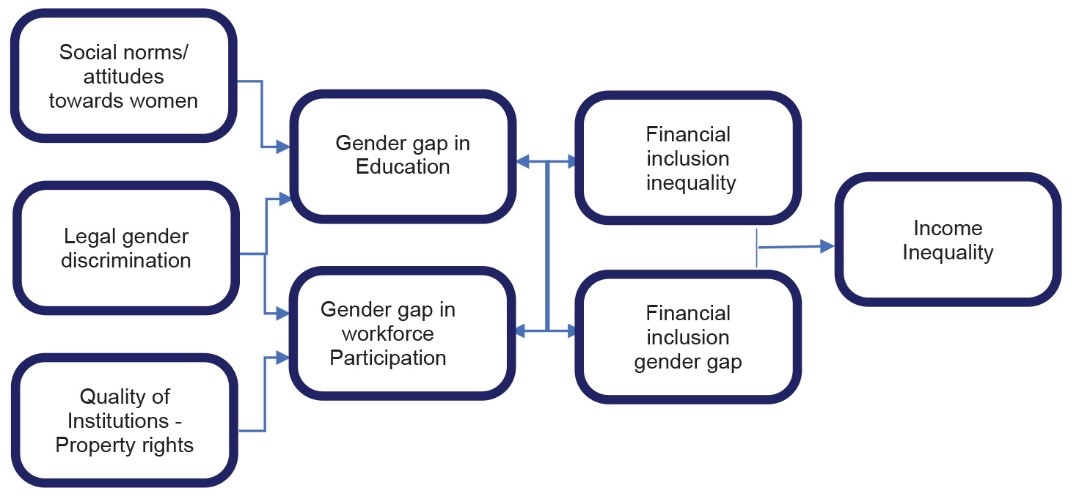

Financial inclusion, women’s entrepreneurship, and sustainable livelihoods are intricately linked to one other. Persistent gender inequalities in access and utilisation of financial products perpetuate economic inequalities, limit access to productive assets, lower opportunities for business expansion, impact education and healthcare access, and reduce labour force participation (see Figure 1). Women’s financial inclusion can provide them with efficient tools and knowledge, leading to improved engagement in income-generating livelihood activities, economic empowerment, and social mobility. Financial inclusion can therefore be a key driver of women’s economic empowerment—in turn essential to achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 on gender equality, which lies at the heart of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Research has shown that women tend to invest savings returns on their families and communities—this has potentially broad economic benefits.[10] Leveraging the various interlinkages within the SDG framework, financial inclusion also directly or indirectly impacts various targets under seven other SDGs all related to people and prosperity. There is also an implicit focus on financial inclusion in SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) for promotion of savings, investments, and increasing consumption rates to spur economic growth.[11]

Figure 1: Gender Gaps in Financial Inclusion and Economic Inequalities

Source: Aslan et. al. (2017) [12]

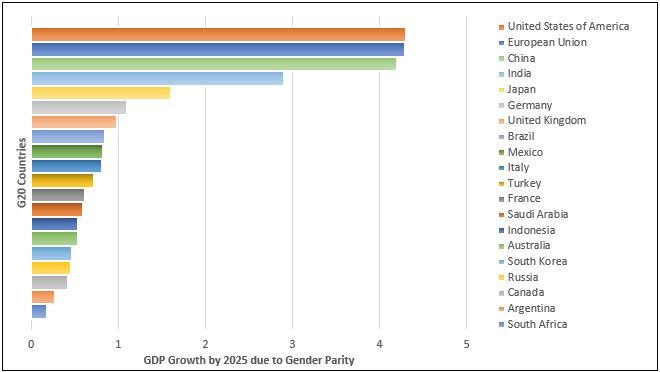

Spurring women-led enterprise will be a key in the global economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic,[13] which disproportionately affected women-led businesses compared to those by men.[14] The task will not be easy. After all, of 190 economies studied by the World Bank Group, at least one gender-based legal restriction exists on women’s employment and entrepreneurship in 86 of them.[15] The result is the feminisation of poverty, and pervasive gender disparities in wealth and income from work.[16] A 2015 McKinsey Global Institute study estimated that alleviating the gender gap in economic participation alone can boost global GDP by as much as US$ 28 trillion by 2025.[17] Among the G20 countries, the United States shows the greatest potential for boosting economic growth through advancements in gender parity. Of the estimated US$ 28-trillion increase in global GDP assuming declining gender disparities, India alone can add US$ 2.9 trillion.

Figure 2: Projected GDP Growth in G20 Countries by 2025, Assuming Absolute Gender Parity[18]

Source: Mckinsey Global Institute[19]

India is among those countries where entrepreneurship among women can provide a solution to the decline in female labour force participation rates, which stood at 25.1 percent in 2020-21.[20] Women’s domestic obligations often lead to time poverty – restricting their participation in formal labour markets and often leaving them less likely to get employed, or else face a wage penalty.[21] Entrepreneurship or self-employment can provide women with the equal opportunity to participate in the economy, while also providing flexibility in time use.

The Mastercard Index of Women Entrepreneurs 2021, which looks at the progress of women in business, ranked India at 57th position among 65 countries.[22] India has 13.5–15.7 million women-owned enterprises, representing 20 percent of all enterprises. These enterprises comprise mostly single-person enterprises, which provide direct employment for an estimated 22 to 27 million people. Women entrepreneurs make up roughly 10 percent of all business owners in India, whose growth is hampered by the lack of supportive conditions for entrepreneurship.[23] The potential for female entrepreneurship, however, is huge: If female entrepreneurship is accelerated in the country, it could create 150–170 million jobs until 2030, according to at least one study.[24]

II. India’s Vision: MUDRA and Jan-Dhan, and Their Impact on Gender Equity

The Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency Limited (MUDRA) must be considered as part of the financial inclusion framework created under PMJDY, which utilises the JAM (Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, Mobile) trinity for digital financial inclusion. The JAM trinity integrates Jan Dhan bank accounts, direct biometric identification under Aadhaar, and mobile phones to enable direct transfers of funds. The success of PMJDY has demonstrated that financial services, when accessed and delivered through digital technologies, have the potential to lower costs, increase speed, and promote greater transparency.[25]

PMJDY has provisions that have enabled the inclusion of women. It dispenses with cumbersome paperwork, allowing the mission to reach out to those who do not have functional literacy. Attempting to ameliorate the overall transaction costs for entry of women-led businesses into the market, these provisions create ground for greater economic participation among women. It offers an overdraft facility of INR 10,000 to the woman of the household for operating the savings account satisfactorily, without asking for security or how she will spend the money.[26] Between 2014 and 2017, the gender gap in account access in India fell from 20 to 6 percentage points. Figures from this year show that more than 55 percent of accounts under PMJDY are held by women.[27]

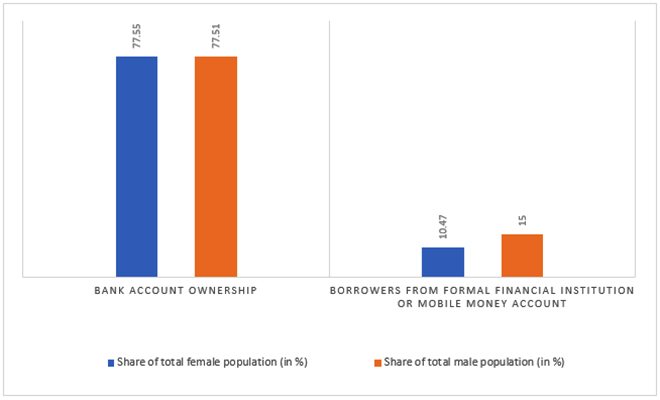

Data from the Global Findex Database 2021 shows that India has closed the gender gap in bank account ownership: 77.6 percent of women have individual bank accounts, compared to 77.5 percent of men. In 2011, only 22 percent of women in India had their own bank accounts.

Figure 3: Population-Level Shares in Account Ownership and Borrowings in India (2021)

Source: Global Findex Report 2021 [28]

Ownership of a bank account alone, however, does not translate to financial inclusion. There are other fundamental elements, including equipping women with tools to save money and access credit—in these aspects, glaring gaps persist. The Findex found that 32.3 percent of women in India have inactive bank accounts. These women’s bank accounts remain dormant primarily because they do not have access to mobile phones and the internet, or else they are unable to operate the accounts because of lack of digital literacy; there is also no regular inflow of cash, and they are often uncomfortable dealing with male bank or business agents.[29] Of the women who do have accounts, less than one-fifth save formally with the bank and for many, usage is limited to withdrawal for emergencies, withdrawing salary, or availing government benefits.

An even greater gap is found in women’s access to credit. According to the National Family Health Survey 2019–21, only 11 percent of women had ever taken a microcredit loan. This could increase in the future, however, as women’s knowledge of microcredit programmes has seen a marginal improvement from 41 percent in NFHS-4 (2015-16) to 51 percent in NFHS-5 (2019–21).

Over the past decade, while the total bank credit to both women and men has increased, the rate of growth for women has been far slower. The total amount disbursed to women still remains abysmally low in absolute terms, according to a 2020 study by the Reserve Bank of India.[30] In 2017, individual women accounted for only 7 percent of total bank credit compared to 30 percent for men.[31] The lack of collateral, due to women’s limited access to assets and property, often hinders them from availing credit from formal sources. The MUDRA Yojana attempts to respond to this gap, by providing collateral-free loans up to INR 1 million for small and micro enterprises. Indeed, women's record at repaying collateral-free micro-loans is found to be better than that of men.[32] The India Delinquency Report[a] found that late payments by male borrowers were at 82 percent, while those by women borrowers were at a far lower 18 percent.[33]

MUDRA was set up with the mandate of “funding the unfunded” micro enterprises in the country. It aims to strengthen last-mile financial institutions by extending refinance and other development assistance to expand their outreach to support micro businesses. The programme seeks to develop the micro enterprise sector into a viable economic sector through financial and business literacy programmes that promote entrepreneurial skills in the rural districts.

PMMY loans are extended by all banks, Regional Rural Banks, Cooperative Banks, Private Sector Banks, Foreign Banks, Micro Finance Institutions and Non-Banking Finance Companies for micro/small business activity in manufacturing, processing, trading, or services sector. The loans are available in three categories: for small businesses, loans upto INR 50,000 are available under the ‘Shishu’ category; loans up to half a million are available under ‘Kishor’; and loans up to a million under ‘Tarun’.

Since most of the beneficiaries under PMMY do not have any credit history, to mitigate the issue of collateral and to support the lending institutions, all eligible micro-loans are covered under a guarantee through the “Credit Guarantee Fund for Micro Units”. The fund is an intervention for facilitating ease of access to institutional credit for the end beneficiary to improve her creditworthiness.

Among the key objectives of the programme is digitisation: emphasising on digital loans, borrowers can apply online through a portal where they can track their credit history and which creates transparency. The State Bank of India, for example, was able to stabilise its PMMY portfolio by introducing end-to-end digitisation, reducing the non-performing asset (NPA) ratio from 15 percent to below 10 percent in new loans.[34]

The inclusion of women is an integral vision of the programme. PMMY encourages women to start their own businesses, potentially shifting traditional mindsets about what women can or cannot do.[35] The Women Enterprise Programme under MUDRA is designed to encourage women entrepreneurs to actively take up loans. Under this programme, financial institutions have been offered an interest rate reduction of 25 basis points (bps) for providing loans to women, incentivising the provision of credit to women entrepreneurs. Data shows that this has worked, and 68 percent of the loans extended under the scheme in 2021 were disbursed to women entrepreneurs.

Since these loans are collateral-free, they require minimum documentation, especially for loans under the ‘Shishu’ category. This has helped in its uptake by rural women, who can often find paperwork to be a difficulty. Nearly 90 percent of women-owned businesses in India are microenterprises, and they are disproportionately smaller in size than other businesses.

To be sure, barriers to financial access exist for both male and female entrepreneurs. However, the level of financial exclusion among women is higher than that among men because of a number of demand- and supply-side obstacles that are particular to women entrepreneurs' access to capital.[36] On the demand side, lack of knowledge about inheritance and property ownership rights, as well as social limitations and a lack of financial literacy force female entrepreneurs to seek financing from informal sources. As a result, on the supply side, it is uncommon for women in India to own property that may be used as collateral for start-up capital loans. About 58 percent of female entrepreneurs in India who start businesses between the ages of 20 and 30 rely on self-financing, largely from their own savings, or else inherited assets or physical property that can be mortgaged.[37]

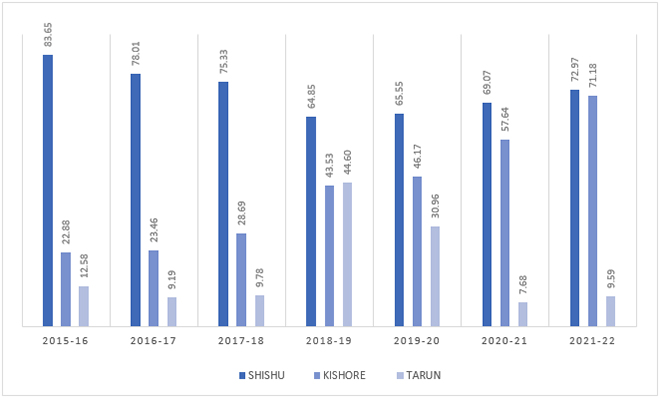

Although PMMY has prioritised lending to women, who depend on higher-interest informal lending more than men, there is a persistent question on how these loans are mostly small-ticket. Of the 68 percent of loans disbursed to women entrepreneurs in 2021, 88 percent were under the ‘Shishu’ category (covering loans up to INR 50,000).[38] The credit needs of women have historically been equated with microfinance.[39] In India, the share of PMMY loans extended under the ‘Kishore’ category (covering loans up to INR 5,00,000) has grown over the years, indicating a gradual transition in women’s credit needs (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Share of MUDRA Loans to Women Entrepreneurs, by Category

Source: PMMY Annual Reports [40][/caption]

Therefore, there is an enduring gender gap in access to credit. According to RBI data, credit received by women is only 27 percent of the deposits they contribute, while the credit received by men is 52 percent of their deposits.[41]

There are no independent evaluations of PMMY’s impact in spurring female entrepreneurship in India. However, the PMMY Annual Performance Reports show that PMMY has facilitated the creation and expansion of businesses owned by women.[42]

There is enough evidence to show that women’s ownership and control of savings accelerate their development, reduce poverty and inequalities, and improve children’s nutrition, health, and academic performance.[43] Women are more likely than men to invest a higher proportion of earnings in their families and communities. Even when the pandemic caused women's monthly household income (MHI) to drop dramatically from INR 12,000 pre-COVID-19 to INR 9,000 after, women who signed up for the programme continued to save because the overdraft feature made the programme an alluring offer. Such propensity to save can ultimately help fulfil the country’s bigger economic goals. To begin with, women comprise a vast consumer segment for banks: as of August 2021, 23.76 crore (237.6 million) of the 42.89 crore (428.9 million) beneficiaries of PMJDY were women. Encouraging these women to save via Jan Dhan Plus accounts can offer a strategic advantage for Public Sector Banks (PSBs), in turn spurring economic resilience.

Like in previous years, the figures for 2022 are likely to reflect a high percentage of women’s participation in PMMY. To help micro businesses recover from the pandemic, there is a renewed focus on PMMY this year. The disbursal of small business loans under PMMY logged a record 30-percent growth in the first half of the current financial year ended September, compared to the same period last year.[44]

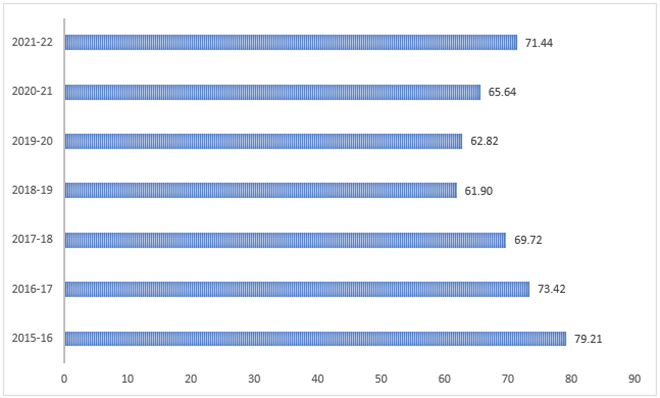

Figure 5: Share of PMMY Accounts Held by Women Entrepreneurs (All Categories)

Source: PMMY Annual Reports [45]

An impact assessment study based on a primary survey, conducted by the Public Policy Research Centre (PPRC) in Delhi-NCR, highlights how PMMY has been able to provide impetus to formal credit access among the marginalised populations.[46] This has led to progressive outcomes with respect to entrepreneurship and job generation. More than one-third (37 percent) of beneficiaries in the sample created new jobs. Loans have also acted as a key instrument to expand the already existing businesses for 78 percent of the beneficiaries in the survey.

Among the challenges that have been highlighted is that the scheme is implementation-intensive and requires high state capability as it involves disbursement of loans to beneficiaries with limited credit histories. It also involves high transaction costs for banks, and the close monitoring of approved smaller loans is administratively difficult. The risk of rising non-performing assets (NPAs) has reduced banks’ appetite to lend unsecured loans to customers with limited credit histories. NPAs, as a cumulative percentage of total MUDRA loans disbursed in FY22, decreased to 3.17 percent from 3.61 percent in FY21, though still higher than the 2.53 percent in FY20.[47]

Financial inclusion can lead to economic inclusion, and vice versa, and yet, gender dynamics exclude women from both.[48] The experience is not unique to India. Women, accounting for nearly one-half of the global population, contribute only 37 percent to the global gross domestic product (GDP).[49] This does not reflect the economic value subsidised by women through the vast amounts of unpaid work they perform for domestic and care activities. Globally, the number of hours that women spend on unpaid care work is three times (3X) that of men; in India, this difference is 8X.[50] The disproportionate burden of unpaid domestic work directly reduces female labour force participation rates; financial inclusion is therefore an indispensable goal.

Financial inclusion of women, through its various interlinkages, can act as an enabler for eight of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals outlined in the 2030 Agenda.[51] While India has made notable progress in women’s financial inclusion along certain measures, it is important to assess whether these improvements have been leveraged to further progress along the various SDGs. While highlighting the gaps that persist in India’s SDG achievements, this will provide indicative evidence for the scope of India’s financial inclusion programmes and strategies in advancing such goals.

Table 1: India’s Progress in Women’s Financial Inclusion-linked SDG Targets

| Sustainable Development Goals | Women’s Financial Inclusion-linked Targets | India’s Indicative Progress |

| SDG 1 (No poverty) | These include: reduce the proportion of women and children living in poverty; creation of sound policy frameworks based on gender-sensitive strategies for poverty eradication actions; ensure equal rights to economic resources for all, including access to basic services and property. | As of 2022, 5.9 percent of the population in India live in extreme poverty. The proportion of employed females living under extreme poverty in 2020 was 9.5 percent, compared to 8.2 percent for men. While poverty rates in the country have declined significantly compared to 2015 levels, the scope remains for addressing persistent gender gaps in poverty alleviation. |

| SDG 2 (Zero hunger) | Related targets include ending all forms of malnutrition in children and addressing the nutritional needs of women and the elderly; double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women. | India continues to face severe challenges to addressing food and nutritional security, with declining or stagnating performance across all related indicators; while cereal yield and productivity has increased (and is on-track to meet 2030 targets), significant challenges remain to sustainable nitrogen management in fertiliser use, increasing costs and impacting profit levels. |

| SDG 3 (Good health and well-being) | These include: reduce the global maternal, infant and under-five mortality ratio; ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services; achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential healthcare services. | The maternal mortality rate has declined to 145 per 100,000 live births with 81.4 percent of births attended by skilled health personnel in 2020; there is no observable gender gap in infant mortality rate but the under-five mortality rate among girls is 35 percent – one-percentage point higher than among boys. Share of women of reproductive age who have their need for family planning met with modern methods has steadily increased to 72.8 percent till 2020, indicating improvements in allied healthcare services. |

| SDG 4 (Quality education) | Related targets include: access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education, and complete free, equitable and quality education for all; access for all to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university; eliminate gender disparities in education, literacy and numeracy. | Sex-disaggregated data for proficiency in reading and mathematics indicate there have been improvements over the years across all levels – progress among females have been markedly higher; Share of female teachers receiving quality technical, vocational and tertiary education is higher than male teachers but exhibits declining trend, bearing implications for women’s employment opportunities and threatening the reversal of progress made in alleviating gender disparities. |

| SDG 5 (Gender equality) | All targets envisaged under goal 5 are directly impacted by improvements in women’s financial inclusion. | In India, the ratio of female-to-male labour force participation rate has been declining since 2015 despite reduction in gender disparities across other development indicators witnessing major challenges – further highlighting the need for women-led small businesses to ensure women’s economic empowerment; share of female population having secure rights over agricultural land has also declined to 35 percent; Proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments stood at 14.4 percent and proportion of women in managerial positions stood at 14.6 percent in 2020, showing slight improvements. |

| SDG 8 (Decent work and economic growth) | These include: sustain a certain level of per capita economic growth; achieve higher levels of productivity through diversification, technological upgrading and innovation; promote decent job creation and entrepreneurship, encourage formalisation and growth of micro-, small- and medium-size enterprises; achieve equal pay for work of equal value for all; protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants. | Proportion of female youth not in education, employment or training is significantly high at 47 percent (but declining) compared to only 13.5 percent among men; the gender gap in informal employment in non-agriculture sector and unemployment rate is biased towards women (primarily due to high concentration of women in agriculture sector as contributing family workers and low labour force participation rates), exhibiting declining trends; Proportion of adult females (15 years and older) with an account at a financial institution or mobile-money-service provider increased to 76.64 percent, showing notable improvements in closing the gender gap in access to financial services. |

| SDG 9 (Industry, innovation and infrastructure) | Related targets are promotion of inclusive and sustainable industrialisation; increase the access of small-scale industrial and other enterprises to financial services; significantly increase access to information and communications technology and strive to provide universal and affordable access to the internet. | India’s progress along SDG 9 has been moderately improving, but crucial challenges remain, hindering its achievement by 2030; The proportion of total population using mobile and internet services have improved significantly – but a 19-percent gender gap in mobile ownership still persists. This has also translated into a 17-percent gender gap in use of digital payments, bearing implications for women’s economic empowerment. |

| SDG 10 (Reduced inequalities) | These include: empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status; ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by discriminatory laws, policies and practices. | Women in India earn only 18 percent of the total labour income compared to 82 percent for men. While gender budgeting can ensure better access to socio-economic benefits among women, promotion of inclusive financing of women-led businesses can create scope for sustainable improvements in economic equality.[52] |

Source: Authors’ own, compiled from: UN Sustainable Development Report, 2022 and UN Women [53], [54]

The gender dimensions of economic issues are largely considered as an equity concern. Yet, they have a direct impact on the efficiency and sustainability of socio-economic systems; there is an economic case to it, in other words. The marginalisation of women and other vulnerable communities, no doubt, leads to normative development challenges such as deprivation from material benefits like food, health, and education. Most importantly, however, it reduces the productivity of the different forms of capital—human, physical, social, and natural—thereby restricting the scope for national development.[55]

Tapping the potentials embodied in women’s economic participation can create opportunities for India to reconcile the “irreconcilable trinity” for its achievement of sustainable economic growth.[56] With women increasingly becoming prominent stakeholders in the Indian MSME sector, collateralised credit and related financial flows within this sector becomes critical to exploring such potentials. It has been observed that the need for ensuring collaterals for credit access has often contradicted the infusion of equity capital needed for business expansion, sometimes leading to undercapitalisation of these businesses, impacting both their efficiency and sustainability and the prospects for Indian economy as a whole.[57] Schemes like MUDRA are a significant step in minimising or resolving these existing contradictions.

III. Learnings from India for the G20 and the Global South

India’s experiences with the Jan Dhan Yojana and the MUDRA Yojana can be made replicable across countries.

The following points summarise the approaches that India has undertaken that have led to improved financial inclusion for women:

IV. The G20 Priorities for Supporting Women’s Economic Empowerment

Women’s financial inclusion is critical to entrepreneurship, economic growth, and sustainable development. The G20 countries have instituted various policies for financial education and inclusion including the G20/OECD INFE core competencies framework on financial literacy for adults.[58] Brazil, for example, has various supporting programs in place such as the “Women in action” program of the São Paulo Stock Exchange that provides women close guidance in learning about formulating business plans. India has identified that educating women about financial principles is key to breaking the cycles of debt, and the Financial Literacy and Women Empowerment (FLWE) program aims to achieve the same. Along with the existing programs, the G20 Employment Working Group (EWG) must focus on a few areas to improve outcomes related to financial inclusivity and economic empowerment of women. These include the following:

Conclusion

India is poised to take the helm of the G20 in December 2022, and has identified advancing women’s economic empowerment and entrepreneurship as one of its priority areas. The country’s experience in promoting financial inclusion in credit uptake by women entrepreneurs can offer important scalable lessons for the developing world and for the G20 economies as well. MUDRA is a reliable alternative to local money lenders and its strength lies in its collateral-free loans and easy documentation.[64] The scheme’s focus on women entrepreneurs has also helped in a higher share of loan disbursements to women—leading to increased monthly household incomes and savings. Most importantly, the financial inclusion of informal women-led businesses has helped push the process of formalisation, thereby making women’s contribution to the economy more tangible and measurable. What remains untapped, however, is the greater deployment of fintech to finance micro loans and bring down operational costs and create greater flexibility and transparency.

Through the G20’s deliberations, India can identify strategies to further advance its efforts towards achieving gender equity in all economic domains, in turn creating scope for social mobility. The G20, as the largest agglomeration of developed and emerging economies of the world, can provide the right platform to promote thought-leadership, delivery of financial and technical assistance, and knowledge sharing among its members and for the rest of the world to advance women’s economic and social empowerment.

Endnotes

[a] The survey was conducted by CreditMate, a SaaS-based debt collection platform by Paytm.

[1] World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Report 2021, March 2021.

[2] Norberto Pignatti, “Encouraging women’s labor force participation in transition countries”, IZA World of Labor, June 2016.

[3] World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Report 2021

[4] “Women at Work in G20 countries: Policy action since 2020”, International Labour Organization and The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, June 2021.

[5] “Women at Work in G20 countries: Policy action since 2020”

[6] “Women at Work in G20 countries: Policy action since 2020”

[7] Salinatri, “G20 MCWE Delegates Acknowledge the Need for Gender Disaggregated Data and Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships for a Better Women’s Entrepreneurial Ecosystem”, G20 Indonesia 2022 News, August 25, 2022.

[8] “Women Entrepreneurs Shaping the Future of India”, India Brand Equity Foundation, January 04, 2022.

[9] “Genesis and Role of MUDRA”, PMMY Portal.

[10] “Investing in Women and Girls”, The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

[11] “Financial Inclusion and the SDGs”, United Nations Capital Development Fund.

[12] Goksu Aslan, Ms. Corinne C Delechat, Ms. Monique Newiak, and Mr. Fan Yang, “Inequality in Financial Inclusion and Income Inequality”, IMF Working Papers, Volume 2017, Issue: 236, November 2017.

[13] The Mastercard Index of Women Entrepreneurs, March 2022.

[14] The Mastercard Index of Women Entrepreneurs

[15] Women, Business and the Law 2022, The World Bank Group, Washington DC,

[16] “Women entrepreneurs can drive economic growth”, remarks by UN Women Deputy Executive Director Lakshmi Puri at the SHE·ERA: 2017 Global Conference on Women and Entrepreneurship, in Hangzhou, China, UN Women, July 17, 2017.

[17] “Growing Economies Through Gender Parity”, Council on Foreign Relations,

[18] The estimate for European Union does not include Bulgaria, Republic of Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, and Slovenia.

[19] “Growing Economies Through Gender Parity”, Council on Foreign Relations

[20] Periodic Labour Force Survey (July 2020-June 2021),

[21] “Facts and Figures: Economic Empowerment”, UN Women, accessed on October 14, 2022,

[22] The Mastercard Index of Women Entrepreneurs

[23] Roshika Singh and Pratibha Chhabra, “Financial Inclusion for Women-owned MSMEs in India”, International Finance Corporation.

[24] Powering the Economy With Her: Women Entrepreneurship in India, Google and Bain & Company, 2019.

[25] Shamika Ravi, “Accelerating financial inclusion in India”, Brookings Report, March 05, 2019,

[26] The Power of Jan Dhan: Making Finance Work for Women in India, August 2021, Women’s World Banking.

[27] “Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) - National Mission for Financial Inclusion, completes eight years of successful implementation,” Ministry of Finance,

[28] The Global Findex Database 2021, The World Bank Group,

[29] The real story of women’s financial inclusion in India, Research Report, MicroSave Consulting, November 2019.

[30] Gender and Finance in India, RBIH White Paper, Reserve Bank Innovation Hub, February 2022, https://rbihub.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Swanari_Whitepaper_small.pdf

[31] Pallavi Chavan, Women’s Access to Banking in India: Policy Context, Trends, and Predictors, Review of Agrarian Studies, January-June 2020,

[32] Abu Zafar M. Shahriar, Luisa A. Unda and Quamrul Alam, “Gender differences in the repayment of microcredit: The mediating role of trustworthiness”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Volume 110, January 2020,

[33] “Women fare better than men in loan repayment”, The Economic Times, December 10, 2019.

[34] Shayan Ghosh, “SBI’s Mudra NPA at 15%, loan book stabilized, says Rajnish Kumar,” June 18, 2020.

[35] Women’s Economic Empowerment in India: Policy Landscape on Financial Inclusion, IWWAGE, LEAD KREA University, March 2020,

[36] Christian Gonzales, Sonali Jain-Chandra, Kalpana Kochhar, Monique Newiak, and Tlek Zeinullayev, “Catalyst for Change: Empowering Women and Tackling Income Inequality”, IMF Staff Discussion Note, SDN/15/20, October 2015, International Monetary Fund,

[37] Women’s Economic Empowerment in India: Policy Landscape on Financial Inclusion

[38] “More than 28.68 crore loans for an amount of Rs 14.96 lakh crore sanctioned by Banks, NBFCs and MFIs since launch of the PMMY”, Ministry of Finance, April 07, 2021.

[39] Elissa McCarter, “Women and Microfinance: Why We Should Do More”, University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class, Volume 6, Issue 2, 2006.

[40] PMMY Performance Reports, PMMY Portal,

[41] Pallavi Chavan, Women’s Access to Banking in India: Policy Context, Trends, and Predictors, Review of Agrarian Studies, January-June 2020,

[42] Annual Report 2020-21, Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency Limited, 2021,

[43] “Investing in Women and Girls”, The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

[44] G Naga Sridhar, “Mudra loans log a record 30% growth in H1 FY23”, October 03, 2022.

[45] PMMY Performance Reports

[46] Pradhan Mantri MUDRA Yojana: An Impact Assessment Study in Delhi NCT, June 2018,

[47] Sandeep Soni, “Mudra NPAs moderate in FY22, though still above pre-Covid levels,” July 19, 2022,

[48] Gender and Financial Inclusion, International Labour Organization.

[49] “Trade & Gender”, World bank Brief, The World Bank Group, March 08, 2019.

[50] Mitali Nikore, “Building India’s Economy on the Backs of Women’s Unpaid Work: A Gendered Analysis of Time-Use Data,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 372, October 2022, Observer Research Foundation.

[51] “Financial Inclusion and the SDGs”, UNCDF

[52] “Why is gender gap widening in India?”, The Hindu Business Line, July 17, 2022.

[53] “SDG Index Country Profile: India”, Sustainable Development Report 2021,

[54] “India”, Women Count, UN Women,

[55]Nilanjan Ghosh and Sangita Dutta Gupta, “The gender lens in development discourse”, Expert Speak, June 12, 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

[56] Nilanjan Ghosh, “How women can change the world”, Commentaries, March 16, 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

[57] Harsh Vardhan, “The low productivity trap of collateralised lending for MSMEs”, IDEAS for India, International Growth Centre, October 07, 2022.

[58] G20/OECD INFE Core competencies framework on financial literacy for adults, The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2016.

[59] Ratna Sahay, Martin Cihak, Papa M N'Diaye, Adolfo Barajas, Annette J Kyobe, Srobona Mitra, Yen N Mooi and Reza Yousefi, “Banking on Women Leaders: A Case for More?”, IMF Working Paper No. 2017/199, International monetary Fund, September 2017.

[60] “Advancing National Strategies for Financial Education”, Russia’s G20 Presidency and The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, September 2013.

[61] Giuseppina Maria Cardella, Brizeida Raquel Hernández-Sánchez and José Carlos Sánchez-García, “Women Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Review to Outline the Boundaries of Scientific Literature”, Frontiers in Psychology, July 2020.

[62] Diana Hechavarria, Amanda Bullough, Candida Brush and Linda Edelman, “High‐Growth Women’s Entrepreneurship: Fueling Social and Economic Development”, Journal of Small Business Management, Volume 57, Issue No. 1, pp. 5-13.

[63] Debasree Das Gupta, “The Effect of Gender on Women-led Small Enterprises: The Case of India”, South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases, Volume 2, Issue No. 1, pp. 61-75, June 2013.

[64] “Pradhan Mantri MUDRA Yojana: An Impact Assessment Study in Delhi NCT”, Public Policy Research Centre, June 2018.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Debosmita Sarkar is an Associate Fellow with the SDGs and Inclusive Growth programme at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at Observer Research Foundation, India. Her ...

Read More +

Sunaina Kumar is a Senior Fellow at ORF and Executive Director at Think20 India Secretariat. At ORF, she works with the Centre for New Economic ...

Read More +