-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Health policy is becoming a prominent poll issue perhaps for the first time in India.

In March 2019, the government released the much-delayed National Indicator Framework (NIF) as well as a provisional version of the official baseline report of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). The progress India makes towards the ambitious SDGs by the 2030 deadline will now be tracked based on the indicators in the baseline report, which is for the year 2015.

This gives India its largest-ever monitoring framework including 306 statistical indicators for SDGs 1 to 16 -- Goal 17 is not considered so far -- covering economic development, social inclusion and environmental protection.

Better measurement, greater evidence and more informed reporting can improve the tracking of the social sector’s performance, and inform voter choice. In fact, more evidence is available to inform the conversation ahead of the impending elections in the form of survey data, and some initiatives involving the NITI Aayog and agencies such as the United Nations.

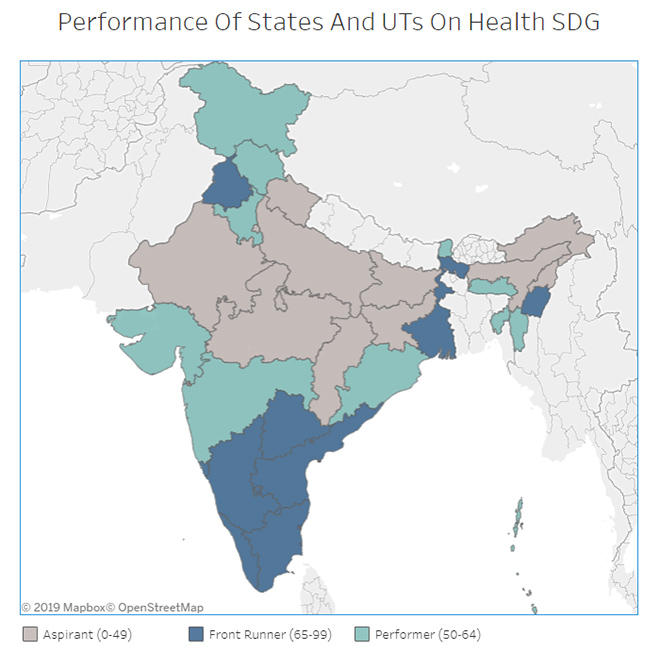

The SDG baseline report by the Niti Aayog highlighted the inequitable nature of the development of healthcare services across the country. Among the top 10 performers within the health SDG, only two states are ruled by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its allies. Three are ruled by the Congress and allies, and five by regional parties.

On the other hand, of the bottom 10 performers, seven are ruled by the BJP and allies, one by Congress and allies, and two are union territories (federally governed areas).

The 2018 Health Index initiative spearheaded by the government’s policy think-tank, the NITI Aayog, and the ministry of health and family welfare, had provided disaggregated scores and rankings to Indian states and union territories according to their health sector performance. The dataset enable an in-depth analysis of state-level performance.

Among the larger states, Kerala (ruled by a coalition led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), or CPIM+), Punjab (Congress+), and Tamil Nadu (All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK)) ranked on top in terms of overall performance.

Uttar Pradesh (BJP+), Rajasthan (Congress), and Bihar(BJP+) fared the worst.

Among smaller states, Mizoram (Mizo National Front-led coalition, or MNF+), Manipur (BJP+) and Meghalaya (BJP+) fared the best, while Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura and Nagaland (all BJP+) fared the worst.

Various component scores of the Health Index throw up interesting state-level patterns. Kerala (CPIM+), Punjab (Congress+), Tamil Nadu (AIADMK) and Maharashtra (BJP+) have already attained the National Health Policy (NHP) 2017 neonatal mortality rate target of 16 per 1,000 live births for 2025, while Kerala(CPIM+) has achieved the SDG 2030 target of 12 per 1,000 live births.

However, Odisha (Biju Janata Dal, or BJD), Madhya Pradesh (Congress+), Uttar Pradesh(BJP+), Rajasthan (Congress+) and Bihar (BJP+) have very high neonatal mortality rates still.

Numbers are not yet available for smaller states and UTs.

Bihar (BJP+), Madhya Pradesh(Congress+), Jharkhand (BJP+), Chhattisgarh(Congress+) and Manipur (BJP+) are shown to have the worst proportion of vacancies of doctors at primary health centres. Manipur (BJP+), however, is one of the best performers within the overall index.

Disaggregated data also show that Arunachal Pradesh (BJP+), Chhattisgarh (Congress+), Haryana (BJP+), Assam (BJP+) and Nagaland (BJP+), who have a low overall score, have nevertheless achieved 100% birth registration.

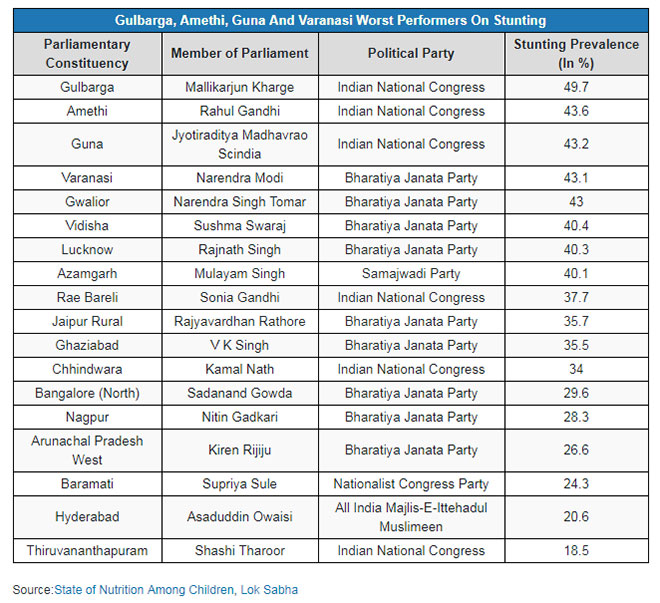

A recent constituency-level analysis of malnutrition has shown how health indicators can enable greater accountability from an electoral perspective, as reported by IndiaSpend on March 22, 2019.

The constituencies of senior national leaders across the political spectrum have high prevalence of various types of undernutrition, the analysis showed. Partly a reflection of its dominant presence in the Lok Sabha (268 against the Congress’ 45), the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and allies represented all but two of the 10 constituencies that performed the worst in stunting.

Health policy is becoming a prominent poll issue perhaps for the first time in India, with the ruling National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government deciding to aggressively publicise the impact of Ayushman Bharat, and Congress president Rahul Gandhi coming out with an announcement that if elected, his party will see to it that 3% GDP is spent on ensuring a right to healthcare for all citizens of India.

In the impending parliamentary elections, with both big national parties already pledging support to substantial efforts towards universal health care, offers India a historic opportunity to open up the conversation.

At the same time, unprecedented access to health information can help track schemes, evaluate impact, and take governments to task, although the quality of the overall health information system in India is not quite up to par.

However, policy discussions remain low and uninformed by evidence and relevant numbers, increasing the risk of fake news derailing otherwise meaningful policy conversations.

The Niti Health Index database covering 24 indicators allowing for state-level ranking across variables, themes, as well as a composite health index remains an underutilised resource. The coming elections are a great opportunity for stakeholders including the media to effectively use it and contribute to a data-informed policy debate.

Over three successive stories by IndiaSpend and the Observer Research Foundation, based on the Niti Health Index database as well as other sources, we will examine states’ health performance across different health domains.

The first in the series will present state-level data and rankings on morbidity, mortality and health service delivery, and present evidence that suggests that a shift away from family planning could free up more resources for health in India.

The next piece would focus on governance issues, some determinants of health and on how centre-state as well as inter-ministry relations play out in health. The final story will look at the key inputs and processes, particularly in terms of human resources, and suggest a way forward.

This commentary originally appeared in India Spend.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Oommen C. Kurian is Senior Fellow and Head of Health Initiative at ORF. He studies Indias health sector reforms within the broad context of the ...

Read More +