-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Lotsmart Fonjong, “The Role of Women’s Nutrition Literacy in Food Security: The Case of Africa,” ORF Issue Brief No. 572, August 2022, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

Africa still lags behind much of the world in food security, which is vital to ending all forms of hunger and malnutrition by 2030—an ambition embodied in the second of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). A March 2022 report from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) noted that of the 44 countries in the world most in need of external food assistance, 33 were in Africa.[1] An analysis by the Global Hunger Index (GHI) in 2021 also revealed that eight of the 10 countries worst hit by severe food insecurity in the world that year were in Africa.[2] Current global supply chain issues and the war in Ukraine have compounded the challenges. In West and Central Africa for example, the number of people suffering from food and nutrition insecurity has risen from 10.7 million in 2019 to 41 million in 2022.[3]

Food security exists when all people at all times have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.[4] The FAO identifies food availability, economic and physical access, stability, and nutritional utilisation as the four pillars of food security.[5] Although it does not explicitly mention nutrition literacy, the FAO recognises that knowledge of nutrition and childcare, in conjunction with access to sanitation and healthcare, are indispensable to food security.

National food sufficiency and food security should be central to Africa’s development agenda. Food sufficiency will help reduce the continent’s dependence on food aid and food imports and prevent social and political instability. Nutritional security is key to children’s development: a well-fed child is likely to be better educated. Africa needs to mobilise its entire population and adopt a multi-sectoral approach to realise its food security goals. Key to this ambition is the role of women. For example, the UN-Women has noted that child nutrition and health, among others, improve when women are financially empowered.[6] Their empowerment also includes nutrition literacy, and the acquisition of other skills that they require to be able to fully participate in all sectors of society.

As the FAO has pointed out, a balanced diet and nutrition utilisation require nutritional intake, good food preparation, and proper feeding habits. In Africa, it is mostly the women who grow, buy, prepare, and serve food to their children and the family.[7] Unfortunately, nutritional information on what an average household consumes is not readily available. Thus, investment in nutrition literacy for women is critical to reducing any gaps in balanced diet and nutritional utilisation. This brief is a desktop study of how food policies and programmes across the continent are addressing the issue of nutrition literacy among women.

Food Insecurity in Africa: An Overview

Food security is under threat globally due to disruptions caused by conflicts, the COVID-19 pandemic, and climate change. The situation in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) might be more alarming. While less than 10 percent of the global population faced severe food insecurity in 2018, the figure for the SSA was over 25 percent. Seven of the 10 countries ranked worst on the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2021 were in SSA.[8] The region has the biggest numbers of malnourished people and stunted children, as well as the highest under-five mortality rates in the world. Even prior to the pandemic, in 2019, Africa’s[a] undernourishment rate was 19.1 percent, while 31 percent of its under-five children were stunted.

Studies have warned that Africa will not be able to achieve the SDG-2 of zero hunger by 2030. The chances of the SSA nations doing so are even lower, considering that people’s diets in the subregion are largely inadequate in proper nutrition. In West Africa, increase in adult obesity, hypertension and diabetes rates are also worrisome, the first having risen by 115 percent in 15 years since 2004. In the same period, the incidence of hypertension spiked to 38.7 percent in Cape Verde and 17.6 percent in Burkina Faso, while diabetes went up to 17.9 percent in Dakar, the capital of Senegal.[9]

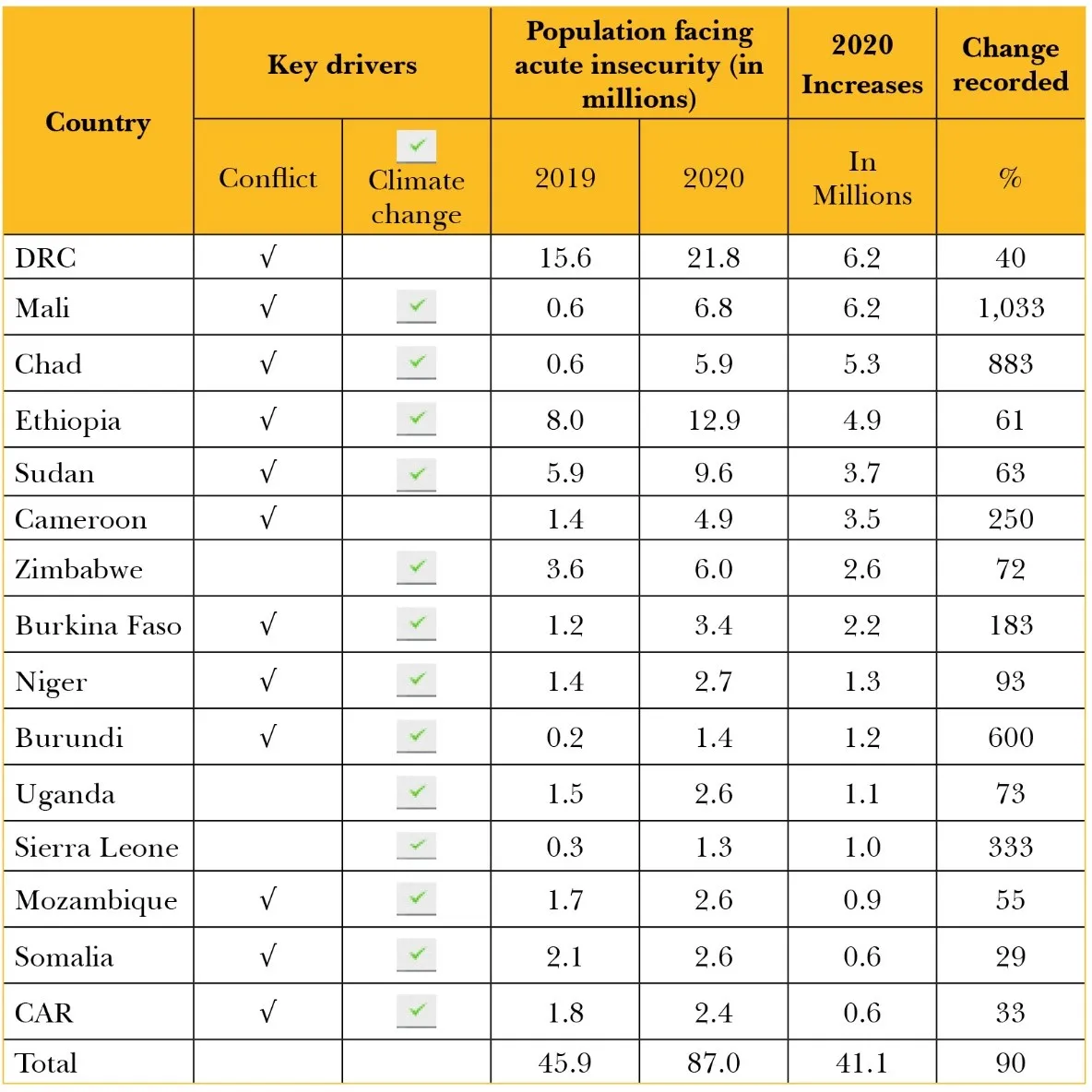

Table 1: African Countries Suffering Heightened Food Insecurity

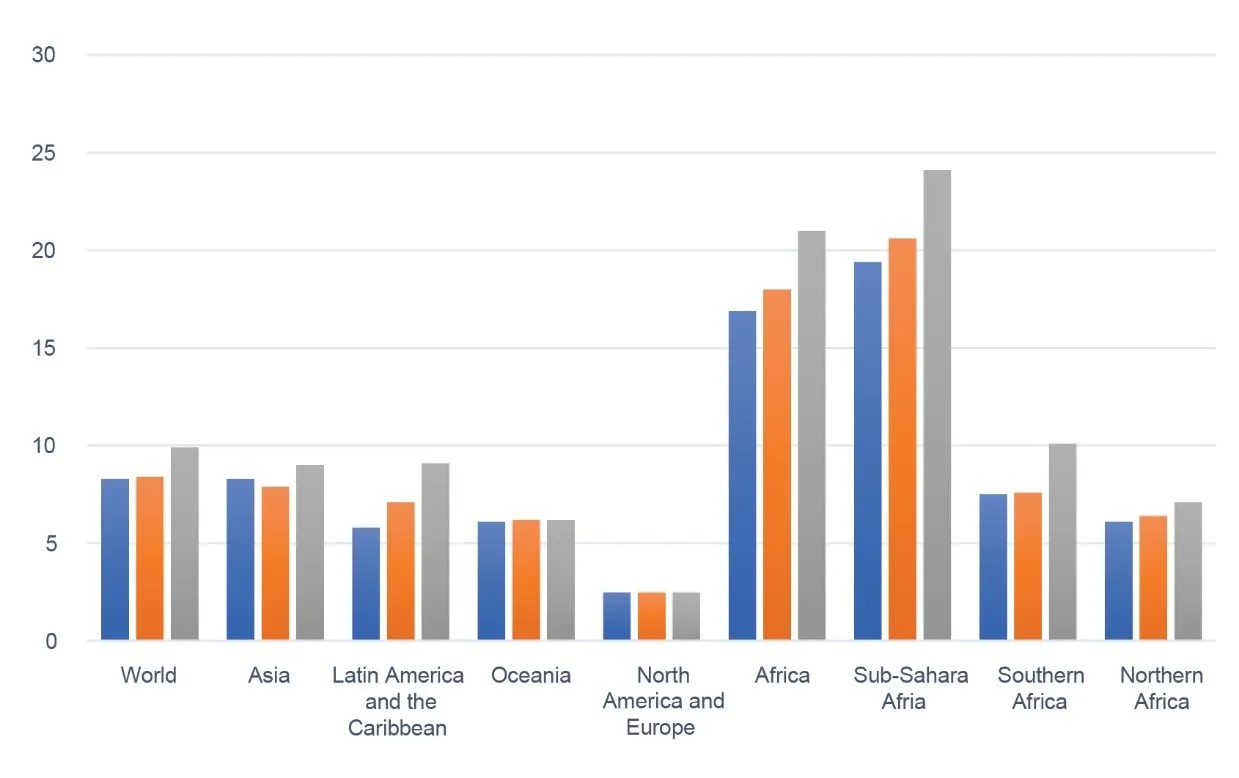

Table 1 shows that in just one year, 2020, the population facing acute food insecurity across 15 SSA countries rose by 41.1 million (or 90 percent). The situation was particularly alarming in Chad, Mali, and Burundi, where the number has gone up by over 500 percent. The increased insecurity in turn has caused even more undernourishment (see Fig. 1) and impacted children’s health. The Global Hunger Index 2021 reported that the under-5 mortality rate was 11.7 percent in Somalia, 11.4 percent in Chad, and 11 percent in Central African Republic, against the global average of less than 4 percent. At the same time, 32 percent, 35.1 percent and 40 percent of children, respectively, from these countries were stunted, compared to the global average of 22 percent. In 2017, more than one-third of stunted children in the world were in Africa, with SSA countries having a shade-higher prevalence rate of 33.9 percent.[10] In the 16 West African countries, the proportion was 30.9 percent. The incidence of ‘wasting’ among West African children was 6.9 percent, 2 percent higher than the global figure.[11]

The causes of this precarious food situation are similar – conflict and climate change. Somalia has experienced conflict for over 30 years and Sierra Leone for 11. Mali, Chad, and the countries in the Horn of Africa have all suffered from weather extremes (droughts and cyclones) due to climate change. They tell the story of the food security situation of Africa – a story of poor governance that fuels conflicts, and sometimes neglects the role of women.

Fig. 1. Undernourishment Rates, Africa and the World (2015-2020, in %)

In the wake of COVID-19, the FAO has pushed for national investments across the globe to start social protection programmes, maintain global food trade, sustain domestic supply chains, and help smallholder farmers raise food production.[12] Other agencies have advocated synergies that integrate peace-building into food systems, especially in regions like Africa. However, it is known that food availability and access do not necessarily assure food security; as the World Bank has noted, the relationship between availability and access, and nutrition outcomes, is complex.[13]

Achieving food security requires a holistic approach that also integrates women and nutrition literacy. Nutrition is an integral part of food security, and nutrition literacy can be a useful predictor of adherence to healthy diet patterns;[14] women are important vectors in this domain.[15]

Nutrition Literacy and Food Security Policies in Africa

For long, efforts to fight malnutrition in poor countries have focused on improving food availability and affordability.[16] Only recently have they begun looking at other aspects including nutrition literacy and dietary diversity. Newer studies indicate that nutritional education improves nutritional outcomes.[b],[17] While everyone in Africa needs nutrition literacy, women need it most, given their position as food providers and caregivers in their households.

The goal of nutrition literacy is either to reinforce existing nutritional practices and habits, or advocate changes in behaviours and habits that adversely impact health.[18] Knowledge about how food is produced, processed, handled, sold, prepared, shared, and eaten, and what happens to it in the body—how it is digested, absorbed, and used[19] —should be widely disseminated. The West Africa Brief—a body of eminent experts of the region and backed by leading development finance institutions—argues that in Nigeria, for example, more than income poverty, poor food choices are responsible for nutritional disorders and malnutrition.[20] Nutritional disorders can translate into various health concerns. In West Africa, for example, in 2021, while 15.2 percent of infants were underweight, 5.6 percent of men and 15.6 percent of women were found obese.[21] When women are educated about good nutrition and how to prepare healthy food, the dietary habits,[22] health, and capacity for food preservation of their families, are likely to improve.

The FAO believes that as caregivers, women influence nutritional security through feeding practices (breastfeeding and food preparation), and health and hygiene practices.[23] In some instances, households that can afford quality food still suffer from undernourishment because of poor nutritional knowledge. Women’s nutritional knowledge is important to avoiding vitamin deficiency as it will enable them to provide their families with the right foods even with limited resources. Pre-pregnancy nutrition, and nutrition during the lactation period, affects the quality of breast milk, and the weight of the newborn and their chances of survival.[24]

A study of 300 children under five years in Northeast Nigeria shows the importance of literacy to child nutritional status. It found that with 65 percent of the mothers/caregivers lacking formal education, 67 percent of the children were underweight, wasted or stunted.[25] Another study from Liberia reported that when mothers had better income and literacy, and breastfed their babies exclusively for the first six months, the latter were unlikely to suffer from severe malnutrition.[26] In South Africa too, it has been observed that socio-economic status, nutritional knowledge, and attitude of caregivers all have an influence on dietary style.[27]

Global gender inequality in food security is well-documented. During COVID-19, for example, food insecurity among women was 10-percent higher than among men,[28] and even more so in developing countries. Nutritional problems in Africa result from insufficient intake relative to nutritional needs.[29] Much of the food consumed in SSA are produced by small farmers[30] who themselves are highly vulnerable to food insecurity and poverty,[31] and who are also largely women. Another factor is that thousands of African rural women have been displaced from their farms by corporate investors, largely from the global North.[32]

The 1996 Rome Declaration on food security[33] underscored the role of women in achieving the goals. A much-cited 2000 study by Lisa C. Smith and Lawrence J. Haddad on child nutrition[34] attributed the decrease in hunger between 1970 and 1995 in developing countries to improvements in women’s status. Yet gender food discrimination has persisted. In some rural households, girls are more vulnerable to food insecurity than boys because of norms and practices that restrict their access to certain foods. Where food is scarce, women eat last or eat leftovers, and may not eat some types of food at all because of gender food taboos. Such bias in food allocation between boys and girls has been reported from other countries such as India.[35] It is common to find rural areas in Africa where girls are given less to eat than boys, or are denied nutritious foods such as legumes, eggs, chicken, and meat.

A survey of 25 African countries showed that those with low gender inequality, such as South Africa and Tanzania, also have low food insecurity, while such insecurity is high in countries with high inequality such as Burkina Faso, Mali, and Chad. In Ethiopia, in households with severe food insecurity, girls were found to be more food insecure than boys.[36] In Kenya, girls had lower energy consumption.[37] And even in low-inequality South Africa, boys were likely to be more food secure than girls in poorer families. However, in families with adequate economic resources,[38] girls were found less food insecure than boys. Similarly, a study in Northeast Nigeria showed that where gender occupational differentials existed, male children were more prone to malnutrition in rural female-headed homes.[39]

The Impact of Women’s Nutrition Literacy

It is important to understand the correlation between women’s literacy—which determines their access to agricultural information—and food security.[40] Women’s illiteracy limits their ability to access and implement agricultural information effectively. Lack of education and agricultural training, poor farming methods and poor post-harvest management impact food security, among other factors. The success of food security projects is influenced by women’s nutrition literacy alongside supply of inputs, improved seeds, credit, and land availability.[41]

The following points explain how female nutrition literacy can affect food security in Sub-Saharan Africa:

Fostering Women’s Nutrition Literacy in Africa

Investments in agricultural technology, food production and availability do not necessarily lead to enhanced nutrition, particularly that of women, because gender power dynamics define who has access to, and control of, their benefits. Thus, rights, power, and access to land resources are crucial to food security in Africa.[49] Women’s empowerment is central to the convergence between agriculture and household nutrition security.[50] But how well women make strategic decisions will depend on their education, their access to information and control over resources, among other factors.

Women often desire to make household diets more nutritious, particularly for the vulnerable, but fall short because of lack of empowerment[51] and lack of information.[52]

The FAO has noted that as caregivers, women influence nutritional security through feeding (breastfeeding and food preparation) practices, and health and hygiene practices.[53] As caregivers, women’s nutrition knowledge helps avoid vitamin deficiency by providing the family with the right kind of food rich in minerals and vitamins, even with limited resources. It also depends, however, on the woman’s age. In Cote d’Ivoire, for example, older mothers are believed to have more experience and better knowledge of food and the nutritional needs of the family than their younger counterparts.[54]

In 2012, then UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon launched the Zero Hunger Challenge (ZHC) to promote an integrated response among UN agencies to the interconnected problems of hunger and malnutrition.[55] There are many examples in Africa where UN agencies are collaborating with the government under the ZHC initiative to develop guidelines on healthy, nutritious, and sustainable diets for children, provide humanitarian food assistance, promote nutrition sensitive agriculture, and build skills for small rural farmers.[56] These collaborations should be gender-inclusive at all levels. Projects such as those by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) to finance rural women or UNDP’s Rain4Sahara to promote agricultural diversity[57] should be encouraged and replicated. However, these should also provide women the means to increase production by focusing on nutrition literacy, helping them make crop and food choices that are nutritious.

In Ghana and Kenya, education at the primary and secondary levels includes basic nutrition education. Government sectors, non-government and civil society organisations should design and implement broader initiatives to improve women/caregivers’ literacy on diet diversity and food production and utilisation.

A study in Ghana showed that nutrition literacy programmes have a positive correlation with diet choices and dietary behaviour.[58] Another in Kenya carried out by the FAO between 2016 and 2020 that combined nutritional education with rural livelihood support, showed that over 80 percent of female participants were able to improve on the quality of their diets.[59] Studies of this nature should be encouraged in other countries and at regional and continental levels. They can provide vital information on how investing in women’s nutrition literacy leads to increased consumption of nutritious food.

Ultimately, female nutrition literacy in Africa is only one part of a comprehensive solution that will enable women’s equal access to resources and women’s empowerment. This in turn will:

Conclusion

As women-headed households grow in number, lack of women’s nutrition literacy—and the absence of empowerment, overall—makes their families more vulnerable to natural and socio-economic adversities. The future of food security in Africa depends on various factors that are intricately linked to good governance and effective policies. Good governance can reduce instability and conflict in the continent and focus public attention on combating climate change, overcoming poverty, and developing social and economic infrastructure that are required to improve living standards.

Nutrition literacy is part of social capital development that can only be achieved through inclusive, broad-based programmes and strategies to promote dietary diversification, positive changes in feeding habits, and balanced diets. Such literacy for women is non-negotiable for a region like Africa where there are food taboos, cultural beliefs and practices that decrease women’s intake of certain nutrient-rich foods and affect the nutritional status of pregnant women.

Sound food policies alone do not always translate into food security for individuals or households. Economic policies pursued by many African countries in the 1970s and 1980s brought about food security at the national level but not at individual households. The effectiveness of national food security policies requires interventions at the household level. This is where the empowerment of women who are both home managers and caregivers, has a crucial role to play. The success of food security policies will depend upon the extent to which local communities are involved in them. Women should be tasked with the leadership of community nutrition programmes, and they must be empowered to do so.

Endnotes

[a] Refers to the entire continent, including the North African states which are not part of Sub-Saharan Africa.

[b] ‘Nutrition literacy’ is defined as the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand nutrition information and skills needed in order to make appropriate nutrition decisions. Food literacy and nutrition literacy go together: they describe the set of knowledge and skills which enable people to make appropriate nutrition decisions and plan, manage, select, prepare, and eat foods.

[2] C. Delgado and D. Smith, 2021 Global Hunger Index: Hunger and Food Systems in Conflict Settings, 2021 Global Hunger Index: Hunger and Food Systems in Conflict Settings.

[3] World Food Program, “Hunger in West Africa Reaches Record High in a Decade as the Region Faces an Unprecedented Crisis Exacerbated by Russia-Ukraine Conflict”.

[4] FAO, Report of the World Food Summit, 13-17 November 1996.

[5] FAO, “The Four Dimensions of Food Security”.

[6] UN-Women, “Facts and Figures”.

[7] Lotsmart Fonjong, “Left Out But Not Backing Down: Exploring Women’s Voices Against Large-Scale Agro-Plantations in Cameroon,” in Development in Practice, (2017)27:8, 1114-112

[8] https://www.globalhungerindex.org/ranking.html

[9] William K. Bosu, “An Overview of the Nutrition Transition in West Africa: Implications for Non-Communicable Diseases,” in Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, vol. 74, no. 4, 2015, pp. 466–477

[10] Africa Development Bank, “Nutrition Facts for Africa”.

[11] Global Nutrition Report | Country Nutrition Profiles – Global Nutrition Report

[12] FAO, “A Battle Plan for Ensuring Global Food Supplies During the COVID-19 Crisis, 2020”.

[13] World Bank, 2007, From Agriculture to Nutrition: Pathways, Synergies and Outcomes. Washington, DC: World Bank.

[14] M. Taylor, et al., “Nutrition Literacy Predicts Adherence to Healthy/Unhealthy Diet Patterns in Adults with a Nutrition-Related Chronic Condition,” in Public Health Nutrition 22, no. 12 (2019): 2157-2169.

[15] FAO, “Agriculture Food and Nutrition for Africa – A Resource Book for Teachers of Agriculture”.

[16] Mequanint B. Melesse, “The Effect of Women’s Nutrition Knowledge and Empowerment on Child Nutrition Outcomes in Rural Ethiopia,” in Agricultural Economics 52, no. 6 (2021): 883-899; Per Pinstrup‐Andersen, “Agricultural Research and Policy for Better Health and Nutrition in Developing Countries: A Food Systems Approach,” in Agricultural Economics 37(2007): 187-198.

[17] Kalle Hirvonen, et al., “Children’s Diets, Nutrition Knowledge, and Access to Markets,” in World Development 95 (2017): 303-315.

[18] FAO, “Agriculture Food and Nutrition for Africa – A Resource Book for Teachers of Agriculture”

[19] F. Savage King, et al., Nutrition for Developing Countries (London: Oxford University Press, 2015) pp. 400

[20] West Africa Brief: Nutrition and Food Security in Nigeria.

[21] Global Nutrition Report | Country Nutrition Profiles – Global Nutrition Report

[22] Katenga-Kaunda, et al., “Enhancing Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Diversity Among Rural Pregnant Women in Malawi: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” in BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 21, no. 1 (2021): 1-11.

[23] Agnes R. Quisumbing, et al., “Women: The Key to Food Security,” Food and Nutrition Bulletin 17, no. 1 (1996): 1-2.

[24] Food and Nutrition Bulletin, vol. 17, no. 1, 1996, The United Nations University

[25] MB Sufiyan, SS Bashir, and AA Umar, “Effect of Maternal Literacy on Nutritional Status of Children Under 5 Years of Age in the Babban Dodo Community, Zaria city, Northwest Nigeria,” in Ann Nigerian Med (2012) 6:61-4

[26] OW Kumeh, et al., “Literacy is Power: Structural Drivers of Child Malnutrition in Rural Liberia,” in BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health 2020; bmjnph-2020-000140.

[27] Risuna Mathye, “Nutrition Knowledge Attitudes and Behaviour as well as Perceptions of Hunger and Food Security of Caregivers in a Resource Limited Community (Bronkhorstspruit) Gauteng Republic of South Africa,” PhD dissertation, University of Pretoria, 2015.

[28] FAO, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World.

[29] FAO, “Agriculture Food and Nutrition for Africa – A Resource Book for Teachers of Agriculture”

[30] Mario Herrero, et al., “Farming and the Geography of Nutrient Production for Human Use: A Transdisciplinary Analysis,” in The Lancet Planetary Health 1, no. 1 (2017): e33-e42.

[31] Kibrom T. Sibhatu and Matin Qaim, “Rural Food Security, Subsistence Agriculture, and Seasonality,” in PloS one 12, no. 10 (2017): e0186406.

[32] Lotsmart N. Fonjong and Adwoa Y. Gyapong, “Plantations, Women, and Food Security in Africa: Interrogating the Investment Pathway Towards Zero Hunger in Cameroon and Ghana,” in World Development 138 (2021): 105293.

[33] FAO, “Report of the World Food Summit, “13-17 November 1996.

[34] Risuna Mathye, “Nutrition Knowledge Attitudes and Behaviour as well as Perceptions of Hunger and Food Security of Caregivers in a Resource Limited Community (Bronkhorstspruit) Gauteng Republic of South Africa”

[35] Elisabetta Aurino, “Do Boys Eat Better Than Girls in India? Longitudinal Evidence on Dietary Diversity and Food Consumption Disparities Among Children and Adolescents,” in Economics & Human Biology 25 (2017): 99-111.

[36] Hadley Craig, et al., “Gender Bias in the Food Insecurity Experience of Ethiopian Adolescents,” in Social Science & Medicine 66, no. 2 (2008): 427-438.

[37] M. Ndiku, et al., “Gender Inequality in Food Intake and Nutritional Status of Children Under 5 Years Old in Rural Eastern Kenya,” in European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 65, no. 1 (2011): 26-31.

[38] Rainier Masa, Zoheb Khan, and Gina Chowa, “Youth Food Insecurity in Ghana and South Africa: Prevalence, Socioeconomic Correlates, and Moderation Effect of Gender,” 2020,105180, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105180

[39]Ashagidigbi, et al., “Gender and Occupation of Household Head as Major Determinants of Malnutrition Among Children in Nigeria,” in Scientific African 16 (2022): e01159

[40] Kevin John McGarry, Literacy, Communication and Libraries: A Study Guide. London: Library Association Publishing, 1991.

[41] Moira Gundu, “The Effect of Literacy on Access to and Utilization of Agricultural Information for Household Food Security at Chirau Communal Lands in Zimbabwe.” (PhD dissertation, University of Fort Hare, 2009).

[42] Isobel R. Contento and Pamela A. Koch, Nutrition Education: Linking Research, Theory, and Practice (Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2020).

[43] Sheryl L. Hendriks, Suresh C. Babu, and Steven Haggblade, What Drives Nutrition Policy Reform in Africa? Applying the Kaleidoscope Model of Food Security Policy Change (2017)

[44] Katenga-Kaunda, et al., “Enhancing Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Diversity Among Rural Pregnant Women in Malawi: A Randomized Controlled Trial”

[45] M Giguère-Johnson M, et al., “Dietary Intake and Food Behaviours of Senegalese Adolescent Girls,” in BMC Nutr. 2021 Jul 22;7(1):41

[46] Melesse, “The Effect of Women’s Nutrition Knowledge and Empowerment on Child Nutrition Outcomes in Rural Ethiopia”

[47] Katenga-Kaunda, et al., “Enhancing Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Diversity Among Rural Pregnant Women in Malawi: A Randomized Controlled Trial”

[48] FAO, 2021, Data: Suite of Food Security Indicators.

[49] Fonjong and Gyapong, “Plantations, Women, and Food Security in Africa: Interrogating the Investment Pathway Towards Zero Hunger in Cameroon and Ghana”

[50] Building Technical Innovation in Nutrition-Sensitive and Gender-Integrated Agriculture.

[51] FAO, “Agriculture Food and Nutrition for Africa – A Resource Book for Teachers of Agriculture”

[52] FAO, “Agriculture Food and Nutrition for Africa – A Resource Book for Teachers of Agriculture”

[53] Lawrence James Haddad, et al., “Food Security and Nutrition: Implications of Intrahousehold Bias – A Review of Literature” (1996)

[54] N. Jonathan, 2021, Explaining the Gender Gap in Food Security in Côte d’Ivoire.

[55] UN, “Pathways to Zero Hunger”.

[56] Prudence Atukunda, et al., “Unlocking the Potential for Achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goal 2 ‘Zero Hunger’ in Africa: Targets, Strategies, Synergies and Challenges,” in Food & Nutrition Research 65 (2021).

[57] Marian Amaka Odenigbo, Patience Elabor-Idemudia, and Nigatu Regassa Geda, “Influence of Nutrition-Sensitive Interventions on Dietary Profiles of Smallholder Farming Households in East and Southern Africa,” in San Francisco: IFAD Research Series. Academia. edu (2018): 1-26.

[58] Janet Agyarkwaa Oti, “Food Literacy and Dietary Behaviour among Day Students of Senior High Schools in Winneba, Central Region of Ghana,” in Journal of Food and Nutrition Research. 2020; 8(1):39-49

[59] F FAO, 2021, Data: Suite of Food Security Indicators

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr. Lotsmart Fonjong is a multidisciplinary scholar and consultant whose work focuses on natural resources gender food security and development issues in Africa.

Read More +