-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Shoba Suri and Sajusha Ashok, “The Role of Women’s Nutrition Literacy in Food Security in South Asia,” ORF Issue Brief No. 601, December 2022, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

The world is currently far from achieving the second of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), zero hunger (which subsumes the issue of access to safe, nutritious, and sufficient food), by 2030. The United Nations estimates that 8.9 percent of the present global population suffers from hunger.[1] Certain marginalised groups—for instance, based on gender, religion, class, caste, and region—experience food insecurity more acutely than others, thereby highlighting the link between the second SDG and other goals, such as SDG-5 (gender equality). The gender gap in food insecurity, which was already stark before the COVID-19 pandemic, has only worsened. In 2021, the gender gap was 4.3 percent, and 31.9 percent of all women in the world were moderately or severely food insecure, compared to 27.6 percent of all men.[2]

Even as South Asia has experienced economic growth in recent decades, nutrition and food security outcomes continue to be inadequate in the region.[3] In 2020, 19.9 percent of the population suffered from severe food insecurity,[4] rising from 13.5 percent in 2017.[5] Regional and gender considerations intersect to impose a double burden on South Asian women. While the global average rate of poverty is 104 women for every 100 men, in South Asia, it is 109 women for every 100 men. Among the working population in South and Southwest Asia, 30.9 percent of women and 25.4 percent of men live in poverty, the highest rates in the Asia-Pacific region.[6]

These statistics raise pertinent questions about the link between gender, and food and nutrition insecurity in South Asia, which this brief attempts to explore. To view these issues in isolation would be naïve and pernicious. This brief examines how factors such as nutrition illiteracy and unemployment determine food security outcomes among women. It also presents certain policy recommendations to overcome these issues in South Asia.

Food Insecurity in South Asia

Despite its strong economic growth in recent years, South Asia fares poorly in the Global Hunger Index (GHI), recording the world’s highest regional hunger level of 27.4 in 2022.[7] According to GHI 2022, South Asian countries reported the highest levels of stunting and wasting. These trends are worrying for a region that is home to 600 million children and where over 33 percent of the population faces extreme poverty, a situation exacerbated by the pandemic. Of the 136 countries assessed, Afghanistan in the worst-ranked (109), followed by India (107), Pakistan (99), Bangladesh (84), Nepal (81), and Sri Lanka (64). Both Afghanistan and India face serious levels of hunger, with scores of 29.9 and 29.1, respectively. Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka also face moderate levels of hunger.

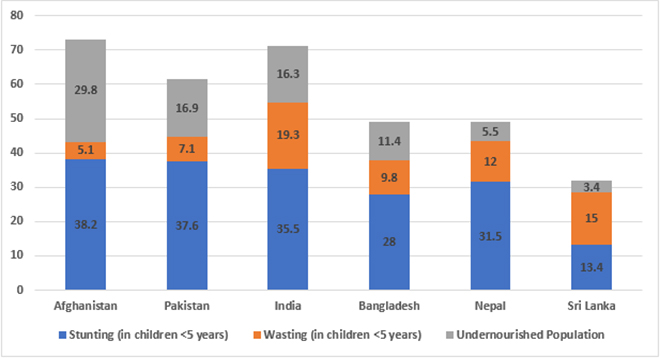

Stunting is the highest in Afghanistan (38.2 percent), followed by Pakistan (37.6 percent), and India (35.5 percent), while wasting among children under five years of age is the highest in India (19.3 percent) and Sri Lanka (15 percent), and the lowest in Afghanistan (5.1 percent) (see Figure 1). In 2022, Afghanistan recorded an estimated 1.1 million malnourished children due to natural calamities such as droughts, political and economic instability, and food and fuel price increases in the aftermath of the Russia-Ukraine war.[8] Afghanistan is also home to the world’s largest undernourished population (29.8 percent). Indeed, the poor nutritional status of mothers and low levels of education have been identified as crucial factors for high stunting in children under five years in South Asian countries.[9]

Figure 1: Global Hunger Index Indicators in South Asian Countries

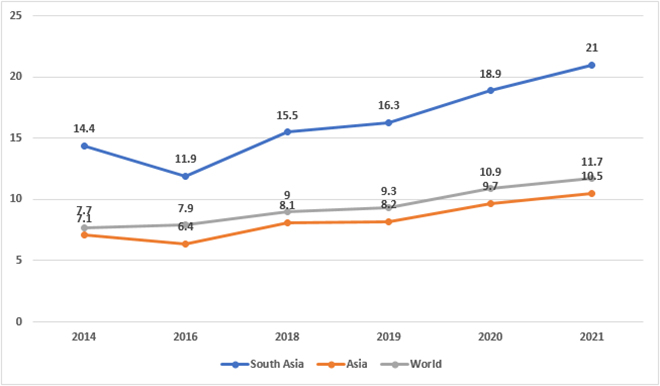

The Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Insecurity Experience Scale indicates an increase in severe food insecurity in South Asian countries, from 14.4 percent to 21 percent, between 2014 and 2021.[10] South Asian countries account for 45 percent of food insecurity globally and 84 percent in Asia (see Figure 2). The data also shows a 4.3-percent gender gap in food insecurity, with 31.9 percent women in South Asia experiencing food insecurity compared to 27.6 percent men.[11]

Figure 2: Food Insecurity Levels* in South Asia, Asia, and Globally

Women, Food and Nutrition Literacy, and Food Security

Food literacy can be defined as “the ability to make appropriate food decisions to support individual health and a sustainable food system, considering environmental, social, economic, cultural, and political contexts”.[12] Nutrition literacy, on the other hand, is the ability to procure, process, and comprehend basic nutritional information necessary to make suitable nutrition decisions.[13] Food literacy subsumes a larger set of skills and knowledge, whereas nutrition literacy is a prerequisite to attain the former. Both terms are complementary in nature and fall within the umbrella term of ‘health literacy.’[14]

The relationship between food and nutrition literacy and food security is twofold: insufficiency in the former can lead to an exacerbation of the latter; and being food insecure can thwart an individual’s ability to use food literacy behaviours to achieve good diet quality. However, even as food literacy can enhance food security through knowledge and skills that can help increase income, food insecurity issues are complex and multidimensional, of which food and nutrition illiteracy is but one dimension.[15]

The role of women in various dimensions of food security cannot be overemphasised. Women play a vital role in sustaining the four dimensions (availability, access, utilisation, and stability) of food security—as food producers, farmers and entrepreneurs; as ‘gatekeepers’ who invest time and income and make crucial decisions that ensure the food and nutrition security of their households and communities; and as managers of food resources in instances of economic crises.[16] Nutrition security—i.e., ensuring sufficient protein, minerals, energy, and micronutrients for all members of a household—remains primarily the domain of women, especially in developing countries. There is an element of care or affective labour involved in ensuring that household members’ nutritional, social and psychological needs are met, which then affects nutrition security through feeding practices and health and hygiene measures. Further, a woman’s nutrition status also determines her child’s post-partum nutrition status. Household food security is also contingent on who earns the income that is spent on food; research has shown that a greater proportion of women’s earnings than men’s are spent on food for the family.[17] Gender inequality and discrimination can thus severely affect the nutrition and food outcomes of individuals worldwide.

A 2020 scoping paper on ‘Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in the Context of Food Security and Nutrition’ details the significant connection between gender equality and female empowerment, and countries’ economic growth and ability to mitigate food insecurity.[18] For instance, Bangladesh deployed a rights-based, livelihood approach to mitigate gender inequalities in nutrition. Research found links between women’s empowerment policies and reduced low birth weight, mortality, infant stunting, and child malnutrition. Evidence also points to a positive correlation between women’s empowerment and enhanced diversity of production. This illustrates that focusing on the role of women during food production and providing them with the agency to make decisions can lead to significant improvements in nutrition outcomes.

Another case in point is EKATA, a project implemented in Burundi to understand how women’s autonomy changes food outcomes. It found that when women took charge of decision making, those assessed experienced lesser food deficit during lean seasons.[19]

Another study conducted in farm households in Tunisia indicated that, although 30 percent of women residing in smallholder households feel ‘disempowered’ (as measured by the Women Empowerment in Agriculture Index, and which includes decisions about agricultural production and over productive resources, and control over income, leadership and time use[20]), there was a positive association between women’s empowerment and dietary diversity, even when factors such as household standards, education, and production diversity were controlled.[21] A study undertaken in the Gedarif and Rahad localities in Sudan also found that households where women engaged in income-generating and farm activities had a greater potential to improve household food security.[22]

There is also a link between women’s empowerment and food access and availability. For instance, the Agrifood Support Program implemented in Nicaragua focused specifically on livestock transfer by providing a livestock package and other specialised assistance in management, commercialisation, and financial literacy. Beneficiaries of the programme, of which 90 percent were women, were given the freedom to choose livestock packages as per the size of their farms and other requirements via non-reimbursable vouchers. The results indicate that food availability increased through improvements in agricultural productivity and livestock production, food access through higher income from the sale of livestock and consumption, and food consumption through o increased protein intake. Additionally, the initiative promoted the creation of farmer groups for training, and women organised and assimilated into communities even after the programme ended.[23]

However, empowering women in the context of food and nutrition security is not without its challenges. Gender inequality is ultimately born of ingrained social norms and biases. To understand and undo entrenched belief systems such as patriarchy by way of policy changes is no easy task. Additionally, cultural considerations aside, patriarchy and gender biases manifest in social institutions, structures, and processes, which are difficult to modify in a short span of time. Further, there is an absence of data capturing, availability, and publications on the impact of gender gaps and discrimination on food security. Formulating policy requires robust information upon which it can be premised, and in the absence of such information it is difficult to enable female empowerment.[24]

Assessing Existing Food Security Policies in South Asia

The South Asia Food and Nutrition Security Initiative (SAFANSI), which aims to confront the ‘South Asian enigma’ of high chronic malnutrition rates despite economic growth, is the most significant food security policy in the region. SAFANSI was implemented in two phases—first, between 2010 and 2015, to push the nutrition and food security agenda in South Asia; and second, beginning in December 2014, which focused on capacity building and driving behavioral changes to improve food security outcomes.[25] The initiative included community-based nutrition programmes that enabled people to control their own nutritional choices and habits rather than relying on centralised actions.[26]

Many South Asian countries also have policies that are geared to improve women’s nutrition and the food security of their families, but there are still many gaps to overcome. In India, for instance, although women constitute almost half of the population (48 percent) as per 2011 Census,[27] they contribute only 18 percent to the GDP as of 2018,[28] indicating the need for significant measures to address the challenges faced by women. Although several policies and programmes exist to tackle food insecurity and malnutrition, these remain gender blind. Thus, the contribution of women to food security and agriculture remains unacknowledged.[29] To illustrate, even though the Hindu Succession Act of 1956 was amended in 2005, it still excludes women from inheriting agricultural land. Further, although women can also be farmers, they are not recognised as such, due to their disadvantaged position with respect to human capital (skill, education, and so on) and bargaining power.[30] The state presently takes a rights-based approach towards food security policy through initiatives such as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, Right to Food Campaign, and the Right to Information Act. An exception to this gender blindness is the 2013 National Food Security Act, a watershed legislation aimed at providing minimum food entitlements to every citizen and contains provisions for providing subsidised food to particular groups, such as lactating or pregnant women. The Act further recognises women as heads of the household in the context of food entitlements. However, it falls short on considering production, procurement, storage, and distribution, and provides only cereals and cooked meals, while neglecting millets and pulses (which are rich in nutrients and more environmentally sustainable, and thus can contribute more to food security.[31]

The Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) programme is Bangladesh’s flagship social security initiative for marginalised groups. The VGD began in the 1970s as a relief programme for the poor and other vulnerable groups, but now also includes initiatives to empower women (for instance, by augmenting their capacity to earn an income). The programme aims to provide women a cash grant to invest, train, and earn a sufficient income to enable an escape from extreme poverty and ensure food and nutrition security over a two-year period.[32] Currently, around 750,000 women are part of the VGD initiative.

Pakistan, which has 37.6 percent stunting and 7 percent wasting in children under five (as of 2017/18), launched its first ever National Food Security Policy framework in 2018.[33] The programme aims to improve food availability, accessibility, and sustainability by supporting households in procuring better-quality agriculture inputs, reducing the cost of loans, improving livestock production, enacting new laws for food safety and marketing, forming a national zero-hunger programme and adopting climate-smart agriculture.[34] However, the country does not have any robust framework for the protection or empowerment of marginalised groups, specifically women.

Bhutan’s Food and Nutrition Security Policy, adopted in 2014, has several goals, including augmenting social access to adequate and safe food, and enabling universal food provision. Similarly, Sri Lanka’s National Agricultural Policy and Nepal’s Agriculture and Food Security Country Investment Plan address issues such as agricultural productivity, livelihoods of farmer communities, and food distribution.[35]

Conclusion

An appraisal of existing food and nutrition security policies in the South Asian countries indicates that there is a need for a more pragmatic and concerted approach towards mitigating gender inequalities and providing women with sufficient agency. However, this must be attempted while acknowledging that such gender biases are ingrained in societal institutions and processes, and thus need to be worked into legislations effectively.

Most existing food security policies in South Asia have gendered inadequacies. To overcome this, the countries must first acknowledge the gender gap in food and nutrition security outcomes, as well as the potential of women’s empowerment in improving these outcomes. This necessitates robust data collection and policy formulation. Several pilot projects aimed at women’s empowerment have already shown potential in countries around the world (such as in Sub-Saharan Africa).[36] It is important that similar initiatives are undertaken in South Asian countries and, more importantly, upscaled to national or regional legislation to help mitigate food insecurity in the area. However, it is equally important to note that women’s empowerment in this region must not be treated as a means to the end of improving food security outcomes. To do so would be to reduce the role of women to a mere economic or social benefit. Instead, the ultimate aim is to eradicate patriarchal norms and the institutions that facilitate such gender gaps in the first place, and enable egalitarianism.

Endnotes

[1] Sustainable Development Goals, “Goal 2-Zero Hunger”, United Nations.

[2] FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO,. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, 2022.

[3] C. Zhou, “Gender Equality and Food Security in Rural South Asia: A Holistic Approach to the SDGs’” NEWSECURITY BEAT, January 4, 2021.

[4] Statista, “Prevalence of Food Insecurity in South Asia 2014 to 2021”.

[6] M. Manjula, “Gender Gap in Agriculture and the ‘South Asian Enigma’,” ORF Issue Brief No. 498, October 2021, Observer Research Foundation.

[7] Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe, “Global Hunger Index”, 2022.

[9] N. Wali et al., “Factors associated with stunting among children under 5 years in five South Asian countries (2014–2018): Analysis of demographic health surveys,” Nutrients 12, no. 12 (2020): 3875.

[10] FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022

[11] FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022.

[12] H. Mohsen et al., “Nutrition and Food Literacy in the MENA Region: A Review to Inform Nutrition Research and Policy Makers.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16 (2022): 10190.

[13] V. Vettori, et al., “Towards the implementation of a conceptual framework of food and nutrition literacy: Providing healthy eating for the population.” International journal of environmental research and public health 16, no. 24 (2019): 5041.

[14] H. Mohsen et al., “Nutrition and Food Literacy in the MENA Region: A Review to Inform Nutrition Research and Policy Makers”

[15] A. Begley et al., “Examining the association between food literacy and food insecurity.” Nutrients 11, no. 2 (2019): 445.

[16] UN Women Watch, “Overview-Food Security”.

[17] IFPRI Food Policy Statement, ‘Women: The key to food security’.

[18] Care, “Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in the context of Food Security and Nutrition- a scoping paper,” September 2020.

[19] Care, “Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in the context of Food Security and Nutrition- a scoping paper”

[20] Lina Salazar and Jossie Fahsbender, ‘Improving Food Security through Women’s Empowerment’, IDB Improving Lives, February 8, 2019.

[21] Marco Kruse, “Assessing the Role of Women Empowerment for Food Security and Nutrition: Empirical Evidence from Tunisia and India,” Dissertation submitted to Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Georg-August-University Goettingen, Germany, May 2019.

[22] FAO, “Proceedings: 1st International conference on food and agricultural economics: assessing the socio-cultural factors that affect women’s contribution to household food security among small scale farmers in Gedarif and Rahad localities of Eastern Sudan“, 2019.

[23] Lina Salazar and Jossie Fahsbender, “Improving Food Security through Women’s Empowerment”

[24] Care, “Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in the context of Food Security and Nutrition- a scoping paper”

[25] The World Bank, “South Asia Food and Nutrition Security Initiative (SAFANSI)”.

[26] The Borgen Project, “The South Asian Food and Security Initiative”.

[27] Census India 2011-Population of India.

[28] McKinsey Global Institute, “The power of parity: Advancing women’s equality in Asia Pacific,” April 2018.

[29] Care, “Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in the context of Food Security and Nutrition- a scoping paper”

[30] Terri Raney, et al., “The role of women in agriculture,”.ESA Working Papers 289018, . Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Agricultural Development Economics Division (ESA), 2011.

[31] Nitya Rao et al., “Gender justice and food security in India: a review.” IFPRI Discussion Papers, 2017.

[32] SR Osmani et al., “Strategic Review of Food Security and Nutrition in Bangladesh,” World Food Programme, 2016.

[33] Pakistan’s Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development-Voluntary National Review, Government of Pakistan, 2019.

[34] Riaz Ul Haq, “New food security policy aims high,” The Express Tribune, April 6, 2018.

[35] United Nations ESCAP, “Realizing sustainable food security in the post-2015 development era,” August 2014.

[36] Hana Brixi and Martien Van Nieuwkoop, “Empower HER to address food and nutrition security in Africa“, October 13, 2022.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr. Shoba Suri is a Senior Fellow with ORFs Health Initiative. Shoba is a nutritionist with experience in community and clinical research. She has worked on nutrition, ...

Read More +

Sajusha Ashok is Masters student in Development Studies at IIT Madras and a former intern with ORFs Health Initiative.

Read More +