-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

The 19th-century English poet Walter Savage Landor once said, “Many laws as certainly make bad men, as bad men make many laws.” This holds true in the troubled state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), which is governed by two contentious laws – one Central and the other a State law – both purportedly aimed at maintaining peace and order. Over the years, the Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act (AFSPA) of 1990 has come under severe criticism for being “draconian” and calls for its revocation have been repeatedly made. However, the state’s political leadership as well as the separatists have been strangely silent on the other law, the Jammu & Kashmir Public Safety Act (PSA), 1978, despite it being slammed as a “lawless law”[1] by Amnesty International and labelled by former Kashmir Committee chief and former Union Law Minister Ram Jethmalani as “something we haven’t heard of even in Nazi Germany”.[2]

Over time, the imposition of PSA, a state law, created a situation where the enforcement of AFSPA by the Centre became inevitable. While the misuse of the former had inadvertently led to the growth of Pakistan-backed insurgency and also triggered a wave of increasingly violent homegrown resistance, the latter had to be implemented to contain the insurgency.

In 1989, when insurgency started in the Kashmir Valley, it had both domestic and foreign dimensions. The insurgency was born as an indigenous movement and targeted primarily the corrupt governance and autocratic rule of Sheikh Abdullah.[3] However, mass rigging of the elections to the state legislature in 1987 created a sense of deep resentment among the people who felt that the sham polls had robbed them of their democratic right to express legitimate dissent against the government in power. The sense of frustration was best expressed by Abdul Gani Lone, former opposition leader and candidate of the Muslim United Front (MUF):

“This simply deepened people’s feelings against the Government of India. If people are not allowed to cast their votes where will their venom go except into expression of anti-national feelings?”[4]

Externally, Kashmir has always been a bone of contention between India and Pakistan, over which the two countries have fought four wars.[5] After the end of the Afghan war in the early 1990s, Pakistan used its war-hardened soldiers and home-bred radicalised jihadis to revive its proxy war and insurgency against the Indian state in J&K. With the help of a section of the Kashmiri society, Pakistan succeeded in making the conflict over Kashmir into the seemingly unending phenomenon that it now is.

Over time, these internal and external dynamics have worked to make the “conflict in Kashmir” – a highly nuanced result of the government’s botched up policies – directly proportional to the “conflict over Kashmir”, one that is a consequence of the unresolved legacy issues between India and Pakistan. Whenever the ‘conflict in Kashmir’ has escalated, the ‘conflict over Kashmir’ has also intensified. For example, from 2016, ceasefire violations (CFVs) – used by Pakistan to provide cover to infiltrators into J&K across the Line of Control (LoC) – have increased enormously in tandem with the escalation of insurgency in Kashmir.

In 2017, India reported 860 CFVs by Pakistan, in which 19 Indian armed forces personnel and 12 civilians died. The same year witnessed 515 cases of infiltration from across the border, in which 75 militants were killed, or 130 percent more than the number reported in 2015. In just 22 days – from 1 January to 22 January 2018—CFVs were recorded on 192 occasions, claiming the lives of eight soldiers and eight civilians.[6]

The Public Safety Act, enacted in 1978 by the J&K government to curb timber smuggling, has since evolved as perhaps the most arbitrary tool in the hands of the state police. The law provides for detention for a maximum of two years in case of persons acting in any manner “prejudicial to the security of the state”. Until its amendment in 2012, it also allowed administrative detention of up to one year for “any person acting in any manner prejudicial to the maintenance of public law and order”.[7] The law thus gives the police absolute power to detain thousands of people on mere suspicion, against whom there may not be any chargeable criminal offence, and “keep them out of circulation”[8]. Prem Nath Bazaz wrote about the impact of the PSA at the time of its imposition:

“The educated Muslim youth, whose number multiplied several times in 30 years, realised that Sheikh Abdullah’s inconsistent behaviour had done immense harm to the interests of the Kashmiris; it had thwarted their progress and deprived them of several political and human rights enjoyed by all the other Indians.”[9]

According to Wajahat Habibullah, former chair of the National Commission for Minorities, the PSA, “the most draconian law of its kind” in India, is of “more universal application” than the AFSPA. It is applied “methodically and universally” in Kashmir.[10] Prevalent only in J&K, the law curtails the protection of personal life and liberty guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution of India. Noted jurist A G Noorani has also said that “if the law (PSA) was enacted elsewhere in India, it would have been instantly struck down by the courts as it violates the fundamental rights bestowed by the Constitution.”[11] Sumit Ganguly, Professor of Political Science at Indiana University once said:

“Indian academics, activists and scholars have written about the PSA and some have argued that it is indeed ultra vires … given its sweeping powers, I would not be surprised that it is, in turn, a cause for further unhappiness and discord.”[12]

A 2010 report by Amnesty International (AI), ‘A Lawless Law: Detentions under the Public Safety Act’, has said that up to 20,000 persons were detained under the PSA since it was enacted in 1978.[13] Over 1,000 detentions were made from March 2016 to August 2017.[14] While arrests under the law continue to be made with impunity, official data show that courts in Kashmir have quashed 1,706 detention orders between 2008 and 2017. The highest number – 215 detention orders – were quashed in 2016 alone.[15]

Despite the numerous PSA orders being quashed, however, frivolous detentions have not only continued but have in fact increased. The police have adopted dubious measures to ensure that the detainees continue to remain behind bars even after the quashing of the PSA charges against them. It is seldom, if at all, that a detainee is able to walk out of prison, owing to what is referred to as “revolving door”[16] detentions or serial detentions designed to keep detainees locked up for years under the PSA, in some cases, even decades. Several other criminal cases are slapped by the police against the detainees during the pendency of the first case, so that when one PSA charge is quashed, another preventive detention order is served even before the detainee is released.

The PSA was amended in 2012 following the recommendations of the then Prime Minister’s Working Group on CBMs.[17] The detention period was reduced to six months from one year for first-time offenders, but the option of two-year detention was kept open to the discretion of the police. Minors were kept out of the purview of the law. However, the amendment has seldom been put into practice, if at all.[18]

The PSA has become a tool for corruption, alienation and radicalisation in Kashmir especially since 2010. This is a worrying trend, as today it is the youth, even stone-pelting teenagers and school boys, who, after prolonged detention under the PSA, are being drawn to militancy.

At the national level, preventive detention is exercised under the National Security Act (NSA) of 1980, which is extended across India except in J&K. Under this law, any person can be detained to prevent him or her “from acting in any manner prejudicial to the defence of India, the relations of India with foreign powers, or the security of India” or public order of any state. The detention cannot exceed three months without any review for first-time detainees. However, unlike the PSA, the NSA communicates to detainees in writing “the grounds on which the order has been made”; they are afforded “the earliest opportunity of making a representation against the order to the appropriate Government.”[19] The NSA also mandates both the Central and State governments to constitute one or more advisory boards of three persons under the chairmanship of a sitting or former High Court judge to look into the matter within “three weeks of detention” and the detainee is provided a sort of legal procedure.[20] Still, the NSA too, has come under widespread criticism for arbitrary detentions.

The AFSPA was first imposed in 1958 in the northeastern states of Assam, Manipur, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Nagaland and Tripura, with the aim of restoring normalcy in “disturbed areas” of the country. It was later applied to Punjab and Chandigarh for 14 years from 1983 to 1997 as a measure against the violent Khalistan movement. In Kashmir, it was introduced only in 1990, despite the Valley having been in the grip of terrorism since the late 1980s.

Notably, the AFSPA has worked towards restoring peace in several other conflict zones of the country. AFSPA was revoked in Punjab in 1997, and it has seen gradual revocation and dilution in the northeast. The Act has been repealed in three out of the seven northeastern states –viz. Tripura, Mizoram and Meghalaya – and has been significantly diluted in Manipur.[21] The AFSPA is expected to be revoked in Nagaland too, following the signing of the peace accord in August 2015.[22]

The AFSPA is invoked when the normal functioning of the state government breaks down and the state, or parts of it, are declared as “disturbed”. The invocation of AFSPA in any state, or parts of it, paves the way for the army to be brought in to restore normalcy in a hostile environment caused by militancy, insurgency or proxy war by a neighbouring country. The AFSPA provides for the protection of the armed forces during high-risk operations and, as such, many of its provisions are deemed to be valid and essential. AFSPA is also a “functional requirement” for the army in terror-hit zones, as the armed forces are mandated to save the country’s critical security installations and equipment.[23] In J&K, Indian armed forces are fighting a proxy war. The AFSPA enables them to fight both the external as well as the externally-abetted forces that threaten not only the security of the state, but also of the country.

There have been sustained – and mostly politically motivated – calls for the revocation of the AFSPA in J&K. Since its inception, the Act has largely failed to achieve any of its primary objectives in the state. The Supreme Court’s observation made in July 2016 that indefinite deployment of armed forces in the name of restoring normalcy under AFSPA “would mock at our democratic process”[24] – made in reference to excesses in Manipur – holds true for Kashmir, too. Ordering a probe against fake encounters in Manipur, the Supreme Court, in its landmark judgement delivered in July 2016, remarked that, “ordinarily our armed forces should not be used against our countrymen and women” and that “every person carrying a weapon in a disturbed area cannot be labelled as a terrorist or insurgent.”[25] Today, these observations could well be equated with Kashmir. Indeed, popular sentiment in the rest of the country – fanned by political vested interests and a sense of misplaced nationalism – has come to largely view all Kashmiris, particularly its agitated youth, as misguided stone-pelters and terrorists.

Over the years, while the allegations of human rights violations under the AFSPA have gone down, similar incidents have increased under the PSA. The period 1990-99 saw 1,170 allegations against AFSPA, coming down to 226 from 2000 to 2004. In the period 2005-09, 54 cases were registered. The number came down to six in 2010, and four in 2011.[26] This was primarily a result of the guidelines issued occasionally by the Supreme Court that have been incorporated as part of the army’s standard operation procedures (SOPs).[27]

Meanwhile, in 2003 alone, 80 percent of the human rights violations cases registered with the J&K State Human Rights Commission were against the Special Operations’ Group (SOG), the voluntary anti-insurgency force of the J&K police. These cases ranged from custodial killings, custodial disappearances, arrests, rapes, molestations, harassment and extortion.[28]

The army has also taken cognisance of many cases and meted punishments to its personnel through army tribunals. In the 104 cases registered against the army in the northeast as well as in Kashmir up to 2013, cognisance was taken by the army within one year. More than 104 personnel, including 39 officers, nine Junior Commissioned Officers (JCOs) and 56 other ranks (ORs), were convicted; their punishments varied from 14 years of rigorous imprisonment to dismissal and other penalties prescribed under the Army law.[29]

However, while the outcry against the AFSPA has become louder among the Pakistan-backed separatists, regional political elite and the local media, the PSA has hardly ever been debated. The high-decibel rhetoric has created an anti-AFSPA perception among the people and further widened the gap between the Kashmiris and New Delhi. Various tragic incidents owing to unethical behaviour by armed forces personnel have also added to the resentment. One example is the Machil staged encounter of April 2010, perhaps the biggest sore point for Kashmiris. The tragic episode was not because of excesses committed under the AFSPA, but a criminal act by an officer for his own vested interests that was twisted to portray the armed forces and its tool, the AFSPA, as draconian.

The infamous Machil “encounter”, in which three men were killed, became a tipping point for the Kashmir unrest in 2010; the ensuing violence left 120 people dead.[30] The army personnel who were involved in the incident claimed that the killings were a result of an armed encounter with terrorists in Machil, close to the LoC, in Kupwara district. A police enquiry, however, concluded that Machil was indeed a staged encounter and all three civilians who were killed were innocent labourers from Nadihal, in Rafiabad.[31] The army court, too, confirmed that the encounter had been simply orchestrated. Five personnel, including one with a rank of Colonel, were sentenced to life imprisonment. The memories of Machil resurfaced in July 2017 when the Armed Forces Tribunal in Chandigarh suspended the sentence on dubious grounds and the five convicts walked free. Though the Army laws are harsh and strictly implemented, arbitrary leniency shown toward delinquent officers, as in the case of the convicted personnel in the Machil fake encounter, has further amplified the demand for the revocation of the AFPSA.

The Shimla Accord of 1975 that came under the backdrop of Pakistan’s defeat and the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, was the “ultimate accession” of J&K with the Union of India. Sheikh Abdullah became the chief minister, but internal tussles between the Congress and National Conference (NC) hindered the smooth functioning of government. Mufti Mohammed Syed, the then J&K Congress chief, decided to topple Sheik’s government with the help of Jammat-i-Islami. Congress had 46 seats and the Jammat had five – a combination that left Sheikh without the required strength in the Legislative Assembly.[32] The Governor dissolved the assembly and fresh elections were conducted within three months.

The Congress – still grappling with the aftermath of the national emergency declared by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi – had just been defeated in the general elections, paving the way for the Janata Party to rule at the Centre. The Janata Party opened its own unit in J&K and received support of many prominent local political leaders.[33] In the first ever free and fair elections in the state in 1977, the Sheikh Abdullah-led NC won 47 out of 77 elective seats of the state. The Janata Party won 13, Congress was successful in 11, and Jammat-i-Islami bagged one.[34] Sheikh, who retained his position as chief minister, became an autocrat and muzzled the voices against him and his party on issues such as misgovernance, corruption, nepotism, and human rights violations. He abused his power for his ensconced and parochial ends.[35]

In November 1977, the Sheikh government passed the Jammu and Kashmir Safety Ordinance Act (SOA) to maintain public order and tackle Pakistan-sponsored adverse activities.[36] The Act put severe restrictions on newspapers and publications in the state. The Janata Party government at the Centre chided the state for stifling civil liberties. Sheikh was forced to dilute the Act, but he refused to abandon it. In fact, the SOA was morphed within a few months into the PSA. The PSA was given legal status in 1978 and made applicable across the state. Though the primary objective of the PSA was to curb timber smuggling, it soon became a weapon to supress political dissent.

Media and academic reports have revealed that Sheikh Abdullah’s real intention was to curb the rising peaceful political dissent against him, especially amongst the educated youth who had been exposed to the political views of their counterparts in mainland India. Thousands of those who voiced their opposition to Sheikh’s authoritative regime were detained under the PSA.[37] The first victim of the PSA was Ghulam Nabi Patel, President of Kashmir Motor Drivers Association (KMDA), who had lent support to the Janata Party in the state elections in 1977.[38]

Intolerance towards dissent, and the imprisonment of opposition leaders led to the erosion of faith in democratic institutions. The situation worsened with the corruption, nepotism and fraudulent recruitments that had become normalised alongside the rampant abuse of the PSA. For instance, recruitments to government posts were being done in the homes of ministers without the issuance of mandatory advertisements against bribes paid by the candidates. Most of the recruitments in the education department were dubious. Out of 400 teachers recruited, 60 were found to be lacking in the mandatory qualifications.[39] By 1985, admissions to premier institutions such as the Regional Engineering College in Srinagar and the Medical Colleges in Jammu and Srinagar were designed to serve political and bureaucratic patronage.[40] The lethal concoction of the PSA, misgovernance and corruption, caused severe social crises and unrest.

The disgruntled people of the Valley, especially the youth, adopted democratic means to challenge the system. In 1987, Islamic groups mobilised a broad coalition under the Muslim United Front (MUF) comprising Jammat-i-Islami, the Ummat-e-Islami and Anjunman-e-Ittehad-ul-Musalman. A large number of educated youth born in the 1960s in prosperous business families became MUF workers.[41] However, the blatant rigging at the hustings ensured that the popular will of the people was not to be realised. The outcome of the elections shocked the people of Kashmir, as the MUF, which was expected to sweep the polls, secured only four seats. The NC-Congress alliance got 66 seats, and NC, 40.

During the elections, the police and the administrative machinery resorted to strong-arm tactics to beat, maim and imprison the MUF candidates and their polling agents.[42] This trend continued long after the election. Members of the MUF were detained under the PSA for months without trial, and tortured.[43] Many of these MUF leaders and their cadres chose to embrace militancy rather than seek justice using democratic and constitutional means. Syed Salahuddin, for example, contested the elections in 1987 as an MUF candidate from the Amira Kadal constituency in Srinagar.[44] After being detained under the PSA for many months, he embraced militancy and eventually emerged as the supreme commander of Hizb-ul-Mujahideen. Like him, most of the first-generation militants were born in police stations, jails and police control rooms in the aftermath of the rigged 1987 election.[45]

As the situation worsened, civilian laws weakened in the face of increased violence and widespread deterioration of law and order. Governor’s Rule was imposed in January 1990. The Centre then invoked the Disturbed Areas Act, paving the way for the implementation of AFSPA. After the elections of 1996, the Disturbed Areas Act was formally enacted as a State Act by the legislature led by the NC government.[46] The AFSPA in J&K followed the tried and tested counterinsurgency methods used in the northeastern states and Punjab. In Punjab, and even in the northeast, the implementation of AFSPA had led to the signing of peace accords with some government concessions relating to grievances and new power-sharing mechanisms. However, the AFSPA has failed to achieve any such positive outcome in Kashmir. Instead of restoration of normalcy, the situation has worsened since 2014, and particularly following the killing in 2016 of Burhan Wani, the widely popular commander of the Kashmiri militant group, Hizbul Mujahideen.

Since the past decade, there has been a lot of debate about the continued enforcement of AFSPA in J&K. Regional parties such as the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) and NC have fought elections promising its revocation. The calls for the law’s annulment have also come from several NGOs following allegations of massive human rights violations. This position has also been taken by Christof Heyns, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions. He said: “AFSPA allows the state to override rights. Such a law has no role in a democracy and should be scrapped.”[47]

At the same time, voices for the retention of AFSPA have been raised by the armed forces, officials of the Ministry of Defence, and some political parties across the country. They argue that AFSPA is needed as peace has not been restored. The armed forces argue that, to begin with, only some special categories of officers are allowed to exercise AFSPA and there are strong internal checks and balances to ensure that the law is not misused.[48] The government has also held many consultations since 2010; however, a final decision on discontinuance of the law has yet to be made.[49]

Between September to November 2017, one of the authors of this paper, Ajyaz Wani, conducted extensive field visits and surveys in the Kashmir Valley. The survey questionnaire was prepared based on deliberations between experts representing the political leadership of Kashmir, local business people and journalists, former diplomats and senior army personnel and academic experts at the ORF conference, ‘Kashmir – A dialogue for peace and integration’ held in Mumbai in July 2017 (see Annexure for the list of participants).

Field surveys were conducted using snowball sampling[50] in different colleges and universities of Kashmir (University of Kashmir, Islamic University of Science & Technology, Awantipora, and Central University, Nowgam) involving a cross-section[51] of students and faculty. Besides students and faculty, the survey included randomly chosen members of the business community, traders, women, local politicians, two senior members of the All-party Hurriyat Conference and members of the J&K People’s League. All 2,300 respondents were asked to answer brief objective-type questions (see Annexure for a sample questionnaire). The primary objective of the survey was to elicit free and frank responses from the youth who constitute an overwhelming majority of the Valley’s population and are stakeholders in the conflict.

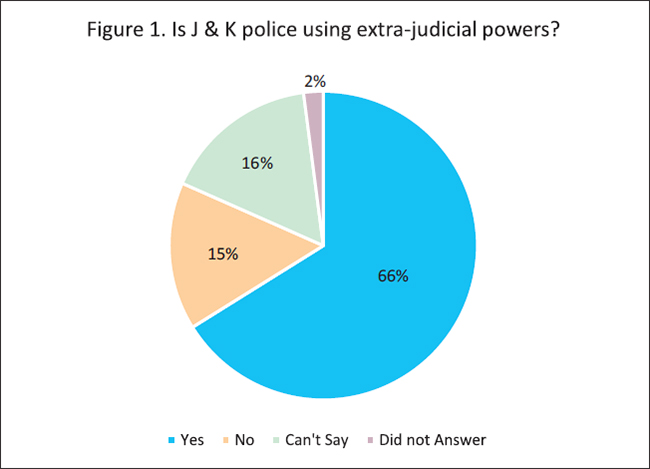

One set of survey questions referred to the roles of the military and the police apparatus in the state – particularly after the unrest of 2016. The question whether J&K police is using extrajudicial powers drew 66.1 percent answers in the affirmative, while 15.5 percent said ‘no’. ‘Cannot say’ was the answer given by 16.3 percent of respondents, while 2.1 percent did not answer the question (See Figure 1). It is not too difficult to ascertain that the ‘extrajudicial powers’ wielded by the police come from the blatant misuse of the PSA. According to respondent Tawseef, a PhD scholar of Political Science in Kashmir University, “people are detained everywhere in India, but Kashmiris are considered second class citizens by government in New Delhi. That is why the PSA was never sent for judicial review to the Supreme Court by the Centre. It is a tool in the hands of state officials and police to extort money.”

Despite Section 23 of the J&K PSA empowering the state government to make rules and standard operating procedures (SOPs) to implement the law, they have not been framed even after 40 years of the Act. This has been admitted by the state home department in response to an RTI.[52] District magistrates and divisional commissioners issue hundreds – sometimes thousands – of detention orders every year under the PSA, merely on the basis of reports and dossiers prepared by the state police, as there are no rules framed under the law for the courts to rely upon.[53]

What journalist Luv Puri wrote in 2010 while arguing for local self-governance in Kashmir as the key to conflict resolution, aptly surmises the “lawlessness” of this law:

“Democracy is not merely about electing the people who man the top echelons of power… J&K is a classic case of institutional failure as several institutions of democratic structure simply do not exist or have ceased to function in the way they are supposed to. In the state of J&K there is a yawning gap between the government and the governed.”[54]

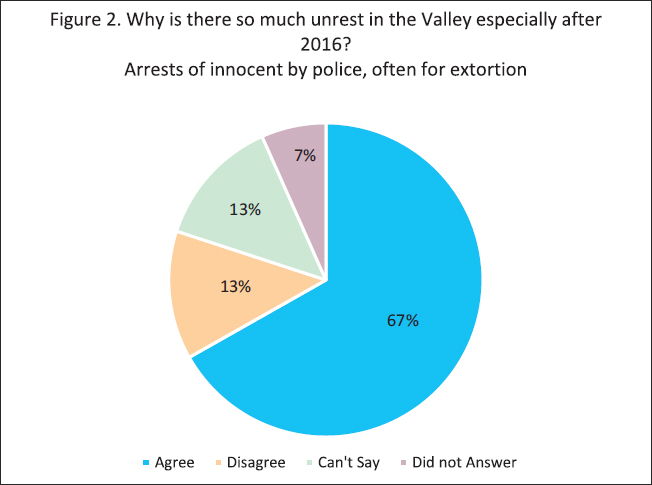

When ORF’s respondents were asked the question of whether the escalation in violence since 2016 was due to arrests of innocent people, often for extortion, more than 66 percent of the respondents agreed, while only 13.2 percent disagreed. ‘Can’t say’ came as a response from 13.6 percent respondents, while 6.7 percent did not answer the question (see Figure 2).

Extortion by the police through numerous detentions under the PSA has virtually become an industry in rural areas of South Kashmir.[55] Interacting with one of the authors of this paper, the residents of Pulwama and Shopian districts claimed that once the police arrest or detain any youth or minor, his father’s contact number is given to brokers who swarm around in the vicinity of police stations. The broker facilitates their access to their ward in the police station. He then demands ransom, which if not paid, would result in slapping of the PSA against the detainee. These young detainees, some in their teens, are then subjected to inhuman treatment and kept with hardline radicals in the police stations including agents of the separatists and even the arrested radicalised Pakistani terrorists, who indoctrinate them with fundamentalist ideology. They are beaten, humiliated and brutalised, until their parents pay the ransom money – typically about INR 20,000 – for their release.[56] Often, the poor parents are left with no resort but to approach the separatists’ camps to seek loans. They do get the money, but on the condition that the youth, once released, will participate in committing violence against the state. Such situations create a soft corner for the separatists among the restive youth, which in turn engenders new problems for New Delhi. The most recent case of extortion was reported from Qazigund. The locals complained that Muhammad Sadiq, a head constable, demanded a ransom of INR 50,000 from the parents of a boy detained for alleged stone-pelting in exchange for his release.[57]

Excesses by security forces, especially by the J&K police abusing their powers under the PSA, have driven many local boys to despair. Physically abused and mentally scarred, some of them have emerged as Kashmir’s second-generation militants, seeking recourse in violent revolt and uprising by joining Pakistan-backed terror groups.

Most of the respondents in ORF’s survey highlighted the examples of Zubair Turray, Sameer Ahmad and Reyaz Naikoo, who joined militancy after 2012. They alleged that Zubair Turray was continuously harassed and a number of false PSA charges were registered against him since 2008.[58] In 2016, he was “charged with instigating people to protest even when he was in custody”.[59] Zubair became a classic example of the ‘revolving door’ method of detention under the PSA and was kept “out of circulation” continuously for four years after his arrest in 2013. He escaped from the Keegam police station on 1 May 2017 and joined militant ranks. While the reason for Syed Salahuddin to embrace violence may have been different,[60] for many other boys like Zubair, the trigger was their arbitrary detention under the PSA and the ensuing torture in lockups. In a video available on the internet, Zubair has clearly said he joined militancy because of “tyranny” and “illegal detention” under the PSA.[61] According to Yasin Malik, Chief of Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), “the state is responsible for Zubair Turray. He was kept under illegal detention for four years and his family was abused in police stations… the police and the PSA are responsible for pushing Kashmiri youth to wall.”[62]

Zubair was killed along with 13 other militants in a joint operation at Dragad and Kachidoor villages of Shopian and Dialgam of Anantnag on 1 April 2018. [63] This operation was hailed by India as one of its most successful anti-insurgency operations in the past decade. Meanwhile, thousands joined in Zubair’s funeral procession, a trend that has become an everyday phenomenon following the 2016 killing of Burhan Wani. Indeed it might be said that funeral processions have become the new recruitment grounds for the Valley’s militants.[64]

Reyaz Naikoo, a close associate to Burhan Wani, was also detained under PSA and joined militancy after his release in 2012.[65] He was named the head of Hizbul Mujadeen after the killing of Burhan’s successor, Sabzar Bhat. He is wanted in several killings including of high-ranking police officers. He carries a bounty of INR 12 lakh on his head.

The other example of radicalisation through detention was Sameer Ahmad Bhat alias Sameer Tiger, who was eliminated by security forces in his hometown Drabgam in Pulwama district on 30 April 2018. He joined militancy in July 2016, a day after his release. He became the main recruiter of militants in Kashmir. According to reports, Sameer Tiger inspired more than 80 local boys to join the ranks.[66] According to his friends, Tiger was frequently asked to report to the police station even when there was not a single criminal charge against him except some cases of stone pelting. One of his friends, a law student at Kashmir University, said it was the police who were responsible for Sameer becoming a militant and not any other security agency. His only fault was that he pelted stones, but he was subjected to inhuman treatment in the police station. Even his father was beaten up by the police on many occasions, his friend said.

Such an “eye for an eye” approach under ‘Operation All-out,’ seeking to weaken the basis of militancy by eliminating the leadership, seems to have been a miscalculated strategy by the Centre. From January to mid-April 2018, 55 militants were killed, of which 27 were local boys.[67] During the same period, more than 45 local youth joined the militant ranks. The new recruits include Junaid Ashraf Sehrai, 26, an MBA degree holder from Kashmir University, and son of Mohammed Ashraf Sehrai, chairman of Tehrek-e-Hurriyat, and Manan Wani, a PhD scholar from Aligarh Muslim University. Most of them are believed to hail from South Kashmir. However, a steep rise in insurgency has also been witnessed in North Kashmir during this period.[68]

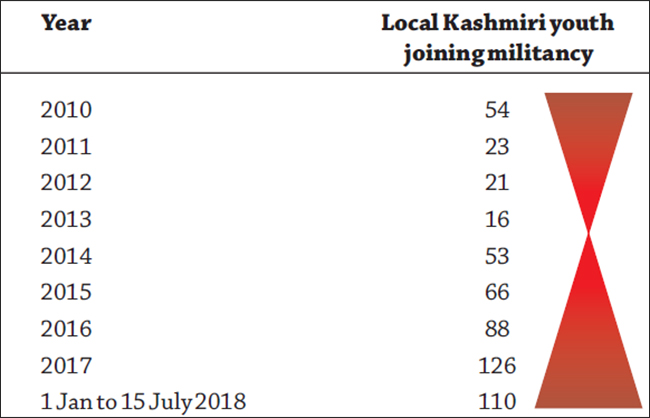

The number of militants joining the rebel ranks has increased enormously in the post-Burhan era. In 2010, 54 youths joined militancy, while the number dipped to 23 in 2011, 21 in 2012 and 16 in 2013. After 2014, the number of local youth joining militancy increased to 53, went up to 66 in 2015 and reached 88 in 2016.[69]

In the past four years, more than 680 militants were killed by armed forces in counterinsurgency operations including 72 in the first four months of 2018. During the same period, 291 security personnel have died in militancy-related incidents.[70] The reasons have been captured by the following media report in 2010:

“Kashmiris have lost the protection of their rights to speech, assembly and travel; they have lost all guarantees of their freedom from violence, harassment and unlawful detention. They have seen every single substantive attribute of democracy give way under the pressure of militarisation and the attitudes of those who administer Kashmir. The rule of law, the independence of the judiciary, and the civic responsibilities of elected politicians: as each of these protective pillars has been hollowed out, all that remains of democracy is the thin patina of elections”.[71]

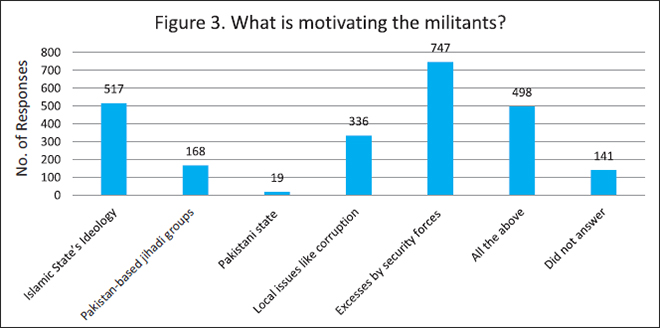

During the ORF survey, respondents were asked to rank prevailing factors that they thought were most instrumental in motivating local boys to join militancy (see Figure 3). The responses were multiple, and included factors such as corruption at local level, Islamic State’s ideology, and Pakistan-based jihadi groups. Two factors are most crucial. One is the influence of Islamic State’s ideology that has spread at an alarming rate because of the provocations of different religious groups omnipresent in the Valley. Indeed, data from Victor Force, Awantipora, in February 2018, shows that of the 117 youth who embraced militancy in South Kashmir in 2017, 18 were radicalised by Islamic State’s ideology in Madrassas, while 47 came under the influence of Islamic State’s ideology during the funeral processions through Pakistan-based jihadi groups. The data did not document the issues of highhandedness by the police under the PSA. However, a vast majority of the respondents in ORF’s survey clearly blamed “excesses by security forces” as the top motivational factor. The other drivers are the Islamic State ideology, and unrestrained behaviour by security forces. It is pertinent to mention that in the same ORF survey, respondents were asked another question: “Who is most ruthless among all security agencies?” Evaluation of the responses reveals an overall “positive” feeling about the role of the Army than the other security agencies, including the J&K police. More than 90 percent of the respondents are of the view that the Army follows SOPs more diligently than any other security agencies.[72]

According to noted criminal lawyer, Mir Shafqat Hussian who has handled hundreds of PSA cases, the divisional commissioners and district magistrates who have to pass the PSA order act largely as rubber stamps. He said that in his entire career, he has come across only two officials who scrutinised the documents carefully before accepting the PSA charges.[73]

Notably, since 2002, all the government interlocutors have recommended the immediate release of all political detainees in the state, as well as comprehensive amendments to the PSA or its abolition.

In September 2010, the Indian government announced the appointment of a group of interlocutors to “begin the process of a sustained dialogue with all sections of the people of Jammu & Kashmir”. The interlocutors advised to the state government that the arrested or detained youth should be freed and all charges should be withdrawn. According to their report, “attention was also drawn to the continuing arrest of youth and the indiscriminate use of PSA against them”. They remarked that “the wide use of the PSA by the state government was criticised by most of the delegations that we met”.[74] However, neither New Delhi was able to do away with draconian law nor the state government did anything to stop the alienation of youth. It remains unclear how many detainees were released on the recommendation of the group of interlocutors.[75]

Former Union Law Minister Ram Jethmalani, a member of the “Kashmir Committee” started by Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee in 2002, said while addressing a press conference in Kashmir on 6 June 2011 that the random arrests, without any charge or trial was not only disgraceful, it was something akin to Nazi Germany. Advocating for the abolition of the PSA, he remarked:

“the need of the hour is to restore democracy, which is nowhere prevailing in Kashmir … maladministration and mis-governance are making people angry and if this is not stopped, Kashmir will boil again.”[76],

His predictions came true in 2016 as rural areas, especially in South Kashmir, which were earlier unaffected by violence, also became the hotbed of uprising. A report published in December 2016 by the Concerned Citizens’ Group led by former External Affairs Minister Yashwant Sinha, after its second visit to the Kashmir Valley, said:

“… There is a deep sense of anger and betrayal against India among the youngsters. Most do not see much of a future for themselves if the Kashmir situation does not settle down. Those arrested for stone-pelting and jailed with adult criminals for lack of juvenile homes are likely to come out as hardened radicals once they are released.”[77]

Dineshwar Sharma, the Centre’s special representative to Kashmir in November 2017, has also urged the quashing of cases against all detainees who have been wrongly apprehended.[78]

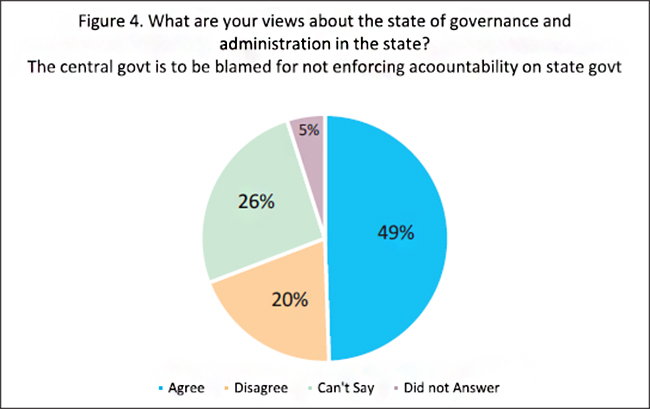

The people of Kashmir largely blame New Delhi for not influencing its power on the state government to make it accountable for its serious omissions. Nearly half of ORF’s respondents (49.5 percent) agree with this view. Only 19.7 percent disagree, 25.9 percent have no opinion to offer, and 4.9 percent did not answer the question (see Figure 4).

The faith of the Kashmiris, especially those born in the midst of conflict since the early 1990s, in democratic institutions and, indeed, in democracy itself, has eroded. The negligible voter turnout in several key constituencies in a series of elections in recent years bears testimony to this fact. The volatile situation has also led to the indefinite postponement of the process of elections, the fundamental prerequisite of any democracy. The by-elections for the Srinagar constituency held in April 2017 were marred by widespread violence and the constituency recorded the lowest-ever voter turnout of 7.13 percent. Not even a single voter turned up in 18 polling stations.[79] Eight persons died and scores were injured, including security forces, on the day of the election. The elections to Anantnag Lok Sabha constituency, scheduled in April 2017, have been postponed indefinitely by the election commission as “the situation is not conducive for conducting polls in the valley as the region is witnessing a spike in violence and protests”.[80] The Panchayat elections, scheduled to be held from 15 February 2018, have also been put on hold.

Things had been different in the past. Notwithstanding the calls for boycott by the separatists, J&K witnessed impressive voter turnouts in all elections held in the past four decades. Even in the contentious elections of 1987 that tarnished the democratic landscape and pushed the Valley into the grip of militancy, voter turnout was between 74.9 percent and 78.6 percent for men, and around 70 percent for women.[81]

It is becoming increasingly clear that the fabric of democracy in Jammu and Kashmir is in tatters. Today the situation is much graver than in the 1990s, as resistance has become totally indigenous. Most of the boys who continue to join militant ranks do not come from across the border. One of the big factors for such widespread alienation is “democracy without rights”, as written by Prem Nath Bazaz in 1978, after the enactment of the PSA. This statement holds true even today and to an even greater degree. Today, if the AFSPA is a necessity of time to control the situation, its rampant abuse has been fundamentally responsible for creating precisely the situation that it wants to control. Most scholars, jurists, government interlocutors, and the youth of Kashmir consider PSA as ultra vires or beyond legal authority. The PSA, as much as the AFSPA, is a strong reason for the negative perception generated among common Kashmiris toward India, the largest democracy in the world; this was not the case till 1980. It is worth noting that it was the common Kashmiris who helped Indian forces defeat the Pakistani raiders and its army in 1947 as well as in the 1965 and 1971 wars.

Digging deep into the recent causes of an unprecedented escalation of the “conflict in Kashmir” through surveys that covered the common Kashmiri people, the authors of this paper have found that the primary reason for a rise in homegrown insurgency is the rampant abuse and misuse of the draconian PSA by the J&K police. It is the PSA and not AFSPA – especially in the past couple of decades – that has driven the youth of the Valley towards radicalisation and alienated them from India and its mainstream sociopolitical framework. With the increasing number of local boys joining militancy because of the misuse of the PSA – and thereby changing the nature of violence in the state with such rise in homegrown insurgency – the state has inadvertently, but certainly, also played into the hands of Pakistan.

The manner in which the PSA has been enforced has served only the vested interests of both the separatists and mainstream politicians of Kashmir. It has thrown the youth against New Delhi. The people of Kashmir consider the law – a brainchild of the Centre, to begin with – as their biggest oppressor; this is evident in the repeated calls for the scrapping of the law. However, after the AFPSA’s review by the Supreme Court, the number of cases of human rights violations by the Army under the Act has declined considerably. On the contrary, despite the amendments, the blatant and arbitrary application of the PSA has witnessed a phenomenal increase and so have the complaints of human rights abuse of the PSA detainees.

There is an imperative to revive the so-called “Vajpayee magic” in the troubled state. Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee, in power from 1998 to 2004, not only discussed with Pakistan the “conflict over Kashmir”, but also took important steps to de-escalate the “conflict in Kashmir”. That strategy worked as a crucial confidence building measure between the two countries. He forced the then Chief Minister Mufti Syed to disband the Special Operations’ Groups (SOGs).[82] Vajpayee’s approach was called “humanistic”, and because of this he is still revered in Kashmir, even in the separatist camps. Over a decade since Vajpayee’s prime ministership, the current situation has become even more volatile as India continues to rise as a global power, and politics in New Delhi has gone through a transformation in the last four years in an environment of increased polarisation and jingoism. Adding to the creation of such an environment is the Centre’s hardline approach on Kashmir, as well as its perceived silence on incidents of majoritarian violence.

It is time that the Centre make the state of J&K accountable once again. New Delhi must urgently refer the PSA to the Supreme Court for a judicial review. Unless the Act is amended, or better still, revoked, it is nearly impossible for either New Delhi or Kashmir to establish any sustainable CBMs and work towards the resolution of the “conflict in Kashmir”. The abolition of the PSA is an inevitable step to create an atmosphere for New Delhi to engage meaningfully with different stakeholders in the state. The interlocutors appointed by government after the uprising in 2010 have suggested that, “In cases of serious charges, the period under which people can be held under the PSA should be limited to one week and after this, due process of law should prevail.”[83] Such major dilution of the PSA, or its total abolition, will give a taste of democracy, and indeed a taste of “freedom” as citizens of India, to those who were born under the dark shadow of conflict, lived through conflict, and have now became victims of both – the “conflict over Kashmir” and the “conflict in Kashmir”.

The revocation of the PSA will help New Delhi prepare a firm timeline for the eventual annulment of the AFSPA. Reassessing the efficacy of both the laws and their eventual revocation must be regarded as inevitable to establish lasting peace and normalcy in the Kashmir Valley and for the real integration of Kashmiris with the rest of India.

Even as the AFPSA is being subjected to review, there is a need to make it more humane in present conditions prevailing in the Valley. For one, the Ministry of Defence should establish armed forces tribunals at the level of the General Officer Commanding (GOC) in South, North and Central Kashmir. A hotline should be set up at each of these GOC headquarters for the people to highlight the grievances against the armed forces in their respective areas. This will help in reducing the trust deficit between the people and work as a new CBM. The establishment of armed forces tribunals at the local level will lend greater transparency in dealing with the complaints of human rights violations. The Army’s proactive feedback to society and petitioners will improve the relations between society and armed forces in general. Furthermore, this law should be made compliant with international and national norms of human rights and humanitarian laws.

Furthermore, as ORF analyst Manoj Joshi has written, “the Army’s law can be harsh but going soft can make things worse.”[84] The Army law should not be softened when it comes to dealing with errant armed forces personnel. There are many examples in Kashmir where Army law was softened to save the armed forces officials – this has provoked resentment among the Kashmiris. Such a softened attitude can be misused by some military personnel to commit gross excesses without any fear of being punished, as happened in the Machil encounter.

All the “Dos and Don’ts” formalised by the Supreme Court should be incorporated in the AFSPA while taking into account the changing nature of counterinsurgency operations. Although the AFSPA has already been suitably amended to conform to the Supreme Court’s guidelines, the amendments should be strictly and honestly put into practice.

Ayjaz Ahmad Wani is a Research Fellow at ORF Mumbai. He is currently working on the project, ‘Kashmir Conflict: Managing Perceptions and Prospects for Peace’. Ayjaz also tracks the minorities of China (the Uyghurs), and issues related to radicalisation in Pakistan and greater Central Asia. He is widely published in national and international peer-reviewed journals. He obtained his PhD from Kashmir University with a dissertation on ‘The State of Uyghur Minority in Xinjiang, China’s Conflict Zone’. He has a Master’s degree from EUCAIS, Germany, where he studied ‘The EU and Central Asia in the International System’, and a second Master’s degree from Kashmir University. He has received fellowships from the UGC as well as the Xinjiang Social Science Academy, Urumchi.

Dhaval D Desai is Senior Fellow and Vice President of ORF Mumbai. His work covers a range of subjects, from urban renewal to international relations. He currently heads research and administration at ORF Mumbai. Dhaval started his career in Mumbai as a journalist, spending 13 years in both print and electronic media. He worked with The Daily and The Indian Express before moving to television news, working in senior editorial positions in Zee News and Sahara Samay. He left journalism in 2006 as the Chief of Bureau of Sahara Samay. He later did a two–year stint with Hanmer & Partners (now Hanmer MSL), a public relations and communications consultancy, where he was part of a World Bank consortium handling communications for a consultant appointed by the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) to study and recommend ways to improve the city’s water distribution.

Q1. Which, according to you, is the most ruthless security agency?

Q2. What is your view about the SOGs?

Q3. Is J & K police using extra-judicial powers?

Q4. Arrests of innocents by police – often for extortion?

Q5. What is motivating the militants?

Q6. Would you blame the central government for not enforcing accountability on state government?

1) Amb T C A Raghavan, Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

2) Lt Gen (Retd) Ata Hasnain, former General Officer Commanding, 15th Corps

3) Dr Shujaat Bukhari, Editor, Rising Kashmir

4) Mr Saifuddin Soz, Congress

5) Mr Nasir Aslam Wani, National Conference

6) Mr Sushil Pandit, Kashmiri activist

7) Mr Ashok Behuria, Fellow and Coordinator of the South Asia Centre, IDSA

8) Dr Sagar Doifode (IAS), Block Development Officer, Bandipora, J&K

9) Mr Jaydeva Ranade, Former Addl. Secretary, Cabinet Secretariat, Government of India

10) Mr Sanjay Nahar, Founder & Director, Sarhad International

11) Mr Mushtaq Ahmad Wani, President, Kashmir Chamber of Commerce & Industry

12) Mr Gowhar Geelani, Journalist, Srinagar

13) Dr Saima Farhad, Assistant Professor, University of Kashmir

14) Dr Prabha Rao, Senior Fellow, IDSA

[1] “A Lawless Law” Detention under Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act (London, United Kingdom Amnesty International Ltd, Peter Benenson House, 2011).

[2] Illegal detentions in Kashmir unheard of even in Nazi Germany, June 7, 2011.

[3] Sumantra Bose, Kashmir, Roots of Conflict Paths to Peace (London; Harvard University Press, 2003): Navnita Chadha Behera, Demystifying Kashmir (Washington D.C: Brookings Institution Press,2006), 41.

[4] Inderjit Badhwar, Jammu & Kashmir; A Tranished Triumph, India Today, 15 April 1987, 41.

[5] Sumit Ganguly and Kanti Bajpai, “India and the Crisis in Kashmir”, Asian Survey, Vol. 34 (5), May 1994, 403.

[6] Happymon Jacob, Giving ‘complete autonomy’ to military not good for either India or Pakistan, Observer Research Foundation, March 10, 2018.

[7] Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act, 1978, Act No. VI of 1978.

[8] Freny Maneksha, The Public Safety Act Is a Political Weapon For the Government in Kashmir, The Wire, December 28, 2016.

[9] Prem Nath Bazaz, Democracy through Intimidation and terror, (New Delhi: Heritage, 1978) 161.

[10] Vivek Chadha, Armed Forces Special Power Act: The Debate (New Delhi: Lancer Books 2013).

[11] A. G Noorani, The Menace of PSA, Greater Kashmir, November 11, 2016.

[12] Email conversation with Prof. Sumit Ganguly on May 21, 2018.

[13] A Lawless law, op. cit.

[14] Gaurav Vivek Bhatnagar, No Rules, Standard Operating Procedures Under J&K Public Safety Act, Reveals RTI, The Wire. January 3, 2018.

[15] Majid Maqbool, Detained Under Public Safety Act, 80-Year-Old Kashmiri Political Activist Completes a Year in Jail, The Wire, October 18, 2017.

[16] Rights group says PSA against Masarat ‘continued violation of rule of law’, Kashmir Reader, November 24, 2017.

[17] Radha Kumar, M.M. Ansari, Dileep Padgaonkar, A New Compact with the People of Jammu and Kashmir, Group of Interlocutors for J&K, Final Report.

[18] Ibid.

[19] The National Security Act, Ministry of Law, Justice and Company Affairs, The Gazette of India, Extraordinary Part II, 27/10/1980.

[20] Ibid.

[21] AFSPA off in Meghalaya, diluted in Arunachal Pradesh, The Indian Express, April 24, 2018.

[22] Sushant Singh, Naga accord is nearly final: No change in state boundary, removal of AFSPA, flag last hurdle, The Indian Express, April 26, 2018.

[23] Vivek Chadha, op.cit.

[24] Utkarsh Anand, Manipur probe: Indefinite AFSPA is failure of Army, Govt, says SC, The Indian Express, July 11, 2017.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Vivek Chadha, op.cit.

[27] Vivek Chadha, op.cit.

[28] Masood Hussain, Mufti disbands SOG, merges force with police; The Economic Times. February 25, 2003.

[29] Vivek Chadha, op.cit

[30] Amit Sing, If the Soldiers Who Killed My Son in Machil Are Let Off, Then Please Just Hang Us Instead’; The Wire. August 9, 2017.

[31] Vivek Chadha, op.cit

[32] Sumit Ganguly, The Crisis in Kashmir, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997) 68-69.

[33] Prem Nath Bazaz, op.cit. 38-39.

[34] Vivek Chadha, op.cit.

[35] Prem Nath Bazaz, op.cit. 152-54.

[36] Prem Nath Bazaz, op. cit. 152-54.

[37] Ruchika Bhaskar & Juhi Srivastava, An Unpublished War: A Critical Analysis of The Public Safety Act and Its Aftermath on the Detainees of Jammu and Kashmir, The World Journal on Juristic Policy, 2016, 7.

[38] Ruchika Bhaskar & Juhi Srivastava op. cit.

[39] Suman Dubey, Congress withdraws support from G.M. Shah Govt, Paves way for governors rule in J&K, India Today, March 31, 1986: Prabhu Chawla, J&K CM Ghulam Mohammed Shah faces charges of large scale nepotism and Corruption, India Today, December 12, 2013.

[40] Wajahat Habibullah, My Kashmir; the Dying of the Light, (New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2014)70.

[41] P.S.Verma, “Muslim United Front”, in Regional Political Parties in India ed. S. Bhatnagar and Pradeep Kumar, (New Delhi: Ess Ess, 1988) 192-95.

[42] Inderjit Badhwar, op. cit.76-8.

[43] Ruchika Bhaskar & Juhi Srivastava op. cit. 73.

[44] I am not Product of 1987 Elections: Greater Kashmir.

[45] Navnita Chadha Behera, op.cit. 47.

[46] Jammu and Kashmir Disturbed Areas Act, 1992 (Act No. 4 of 1992)

[47] Vivek Chadha, op.cit.

[48] The Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act, 1990 No. 21 of 1990, Ministry of Law and Justice (Legislative Department), New Delhi, the September 11, 1990/Bhadra 20, 1912 (Saka).

[49] Vivek Chadha, op.cit.

[50] In conflict environments, the population is marginalised to some degree, making it ‘hidden’ from and ‘hard to reach’ for the researcher. The marginalisation explains why it is difficult to locate, access and enlist the cooperation of the research populations, which, in a non-conflict context, would not have been difficult to do. The Snowball Sampling Method (SSM) is used to address the fears and mistrust common to the conflict environment and increases the facilitates an atmosphere of trust as the researcher is introduced through a reliable social network. For this study, the social network was provided by teachers of different colleges, Universities and academic institutions that helped the researcher generate a friendly and trustworthy environment. In some cases, SSM marks the difference between research conducted under constrained conditions and research not conducted at all.

[51] The age group of the respondents was between 16-30 years, both male and female. Besides, the survey also covered women, business community and young protesters (some of them may have been stone-pelters) in Pulwama district.

[52] Gaurav Vivek Bhatnagar op.cit.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Puri, Luv. Kashmir: Local Self-Governance as the Key to a Solution, Economic and Political Weekly, 45 (32), 2010, 17–18.

[55] David Devadas, Extortion, a major cause for youth alienation in Kashmir, rears its ugly head again, First Post, August 23, 2016.

[56] Ibid.

[57] J&K Cop suspended for allegedly demanding money from families of alleged stone-pelters. Dailyhunt, May 13, 2018.

[58] Abhishek Saha, Kashmiri man joins militants, he was ‘victimised’ under security law, Hundustan Times, May 16, 2017.

[59] Khalid Gul, How the fear of one more PSA turned Zubair into a militant, Greater Kashmir, May 18, 2017.

[60] Hilal Ahmad, I am not Product of 1987 Elections, Greater Kashmir, April 14, 2018.

[61] Abhishek Saha, Kashmiri man joins militants, he was ‘victimised’ under security law, Hundustan Times, May 16, 2017.

[62] Interview with Yasin Malik. April 04, 2018.

[63] Hakeem Irfan, 13 militants, three soldiers among 19 killed in Kashmir, The Economic Times, April 02, 2018.

[64] Harinder Baweja, Kashmirs Disturbing New Reality, Hindustan Times.

[65] M. Saleem Pandit, The New Hizbul Commander In Kashmir, Riyaz Naikoo, Is A Tech-Savvy Terrorist, Indian Times, May 29, 2017.

[66] Sameer Tiger, a stone-pelter who became Hizbul militant, killed in Kashmir encounter: Hundustan times, April 30, 2018,

[67] At least 45 youths from Kashmir Valley join militancy in 2018; security establishment taken by surprise; Financial Express, May 30, 2018.

[68] Ibid.

[69] ‘88 youth took to militancy in 2016’, The Hindu, March 22, 2017.: 2017 saw 126 local youths joining militancy: Mehbooba Mufti, The Times of India, February 6, 2018.

[70] Army can’t be blamed for Kashmiri youth joining militants: Defence minister, Greater Kashmir, May 2, 2018.

[71] Sanjay Kak, ‘What are Kashmir’s Stone Pelters Saying to Us?’ Economic and Political Weekly, 2010, 45 (37): 12–16.

[72] Ayjaz Wani, ‘Human shield’ T-shirts harming Army’s reputation in Kashmir, Observer Research Foundation, April 03, 2018.

[73] Freny Manecksha, The Public Safety Act Is a Political Weapon For the Government in Kashmir; The Wire, December 28, 2016.

[74] Radha Kumar, M.M. Ansari, Dileep Padgaonkar op cit.

[75] Decisions Taken by CCS Regarding Jammu & Kashmir on Saturday, Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, September 25, 2010.

[76] Kashmir reminds of Nazi Germany: Jethmalani, Kashmir Global – News and Research on Kashmir, June 08, 2011.

[77] Report by Concerned Citizens Group’s second visit to Kashmir, December 2016,

[78] Naveed Iqbal, Demands before J&K interlocutor Dineshwar Sharma: From land for house to release of political prisoners, The Indian Express, November 27, 2017.

[79] Shiekh Zaffer Iqbal, Srinagar By-Election: Farooq Abdullah Beats PDP Candidate In Key Contest, NDTV, April 15, 2017.

[80] Smriti Kak Ramachandran, EC cancels Anantnag Lok Sabha bypoll, says situation not conducive, Hindustan Times, May 03, 2017.

[81] Violent bye-polls in Srinagar saw lower turnouts than even the militancy-hit 1990s, Scroll in, August 08, 2018.

[82] Masood Hussain, op.cit.

[83] Radha Kumar, M.M. Ansari, Dileep Padgaonkar op cit.

[84] Manoj Joshi, The Army’s law can be harsh, but going soft can make things worse, Observer Research Foundation, May 30, 2018.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ayjaz Wani (Phd) is a Fellow in the Strategic Studies Programme at ORF. Based out of Mumbai, he tracks China’s relations with Central Asia, Pakistan and ...

Read More +

Dhaval is Senior Fellow and Vice President at Observer Research Foundation, Mumbai. His spectrum of work covers diverse topics ranging from urban renewal to international ...

Read More +