The ongoing crisis in Ukraine has ushered in the worst phase of West-Russia relations since the end of the Cold War. While Washington and Brussels have been clear in their stance (criticism) for Russia, no such transparency can be discerned from Beijing’s response. Confronted with an increasingly unsympathetic West, Russia is visibly turning towards Asia (read China) in order to allay the adverse effects of Western sanctions. In this geopolitical gamble, the biggest beneficiary of Moscow’s reorientation has been Beijing as it now has increased access to Russia’s natural resources.

Putin’s visit in May 2014 to Shanghai came at a time when the West was vehemently criticising Russian actions in Crimea. As if in a mood to retaliate, Russian gas giant Gazprom signed a 30-year gas contract worth $400 billion with the China National Petroleum Corporation. In the same month, Moscow and Beijing jointly carried out naval exercises in the East China Sea, the disputed site between China and Japan. This was obviously not taken well by Japan, but caused greater anxiety in Washington. Both these events have been beneficial for China. In the first instance, Gazprom had to resort to the demand for lower prices by China. The second instance sent a strong message to Washington as the US pivot to Asia also uses Japan and the South China Sea issue to contain China. As Andrew Kuchins from the Centre for Strategic and International Studies puts it "the single biggest benefit is that for China" as this "distracts the United States from carrying out the rebalance to the East" (Eckel 2014).

Moscow’s turn towards Beijing

One needs to ponder why a "declining" power like Russia poses such a serious threat to the West. There are two ways to interpret Russia’s actions in Crimea. First, as the West views it, Putin wants to rebuild the Soviet empire. Second, European Union’s eastward expansion is not taken well by Russia, which Russia believes translates into North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) membership. Probably what E H Carr says is true after all, "Past authenticates the present." Russian insecurity dates back to early 2000s, when NATO expanded itself farther than it had initially promised.

In the face of Western sanctions, Russia needs more strategic partners. China is perhaps the most suitable ally for the former considering its rising influence in global affairs. As Shi Yinjhong from Renming University in Beijing puts it, "Xi is important for Putin, for Russia’s face" (Perlez 2015). When Russian president Vladimir Putin on 7 April 2015 met Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Li in Moscow, he was quick to note that Sino-Russian relations "have reached an unprecedented high and the possibility for bilateral cooperation is completely in line with the reality and long term needs of the two nations" (Embassy 2015). A month later, Xi Jinping was the chief guest at Moscow’s victory parade to celebrate 70 years of victory over Nazi Germany. On the eve of the parade, the two sides also signed 32 bilateral agreements including a pact on cyber security. On the day of the parade itself the presence of a Chinese guard of honour for the first time was also symbolic of growing Sino-Russian ties. Similarly, Putin’s scheduled visit to Beijing on 3 September 2015 to commemorate the Chinese victory over Japan will reinvigorate their growing ties.

While Russia and China may not be the best of friends, what brings the two powers together at this time is mutual need and prospects of gain. Russia is in search of new markets post the Western sanctions against it. As an expanding economy, China has a great demand for natural resources. The simple demand-supply mechanism thus brings the two countries together. Hence, a sort of partnership of convenience between the two can be seen which is beneficial for both. So, while China may not be interested in the developments in Ukraine, it definitely is interested in acquiring resources for its large population.

China is already Russia’s biggest trading partner. Trade between the countries was worth over $88 bn in 2013 and $95.3 bn in 2014. It is likely to grow further as Russia’s trade with Europe contracts. China’s Foreign Minister Wang Li has shown optimism for the current year too, expecting close to $100 bn bilateral trade in 2015 (Porter 2015). Moscow and Beijing have even vowed to take their bilateral trade to $200 bn by 2020. Thus, it may not be an exaggeration to say that Sino-Russian relations have entered a new phase ever since the West levied sanctions on Russia.

Why Is China likely to play safe?

While Sino-Russian friendship stands out in the open, China’s non-committed position on the Russian annexation of Crimea betrays the supreme love for sovereignty that China holds. This goes against the very tenet of China’s foreign policy. Positive response from China can be explained from the fact that China has a poor record of alliances. The post-Crimean annexation scenario has turned in China’s favour by creating a strong support base in Russia. Hence, while it has not been vocal in supporting Russia within the international community, it has not opposed the latter either.

Playing a smart diplomatic card, Beijing has sought to maintain a restrained position with respect to the Ukraine crisis in the international forum. It abstained from voting in the United Nations Security Council, signalling its neutral position on the issue. During his visit to Germany in March 2014, Xi Jinping cleared the air while expressing that "China does not have any private interests in the Ukraine question," and that "all parties involved should work for a political and diplomatic solution to the conflict" (Brown and Breidthardt 2014).

China is a growing Asian giant that has stakes in different regions of the world. In December 2012, the then recently appointed President of the People’s Republic of China Xi Jinping talked of the "Chinese dream" while delivering a speech at the National Museum of History in Beijing. The notion of "Chinese dream" is viewed as a new principle guiding China’s own development and its relations with the rest of the world. It thrives on the twin concepts of "harmonious society" and "harmonious world" (Lim 2013). Of particular interest to China are the "belt and road initiatives" that were first announced in 2013 during his visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia.

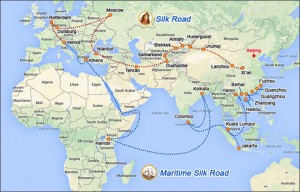

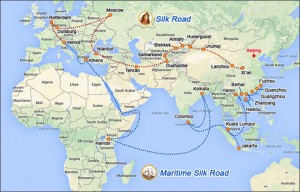

Cordial relations with Europe are a necessity to fulfil Xi’s Chinese dream. As conceptualised, the Silk Road Economic Belt is bound to cover Kazakhstan, Russia and Belarus, ultimately ending in Europe. The following figure outlines China’s ambitious project which, if materialised can result in a complete positive facelift of its geopolitical might.

Source: http://en.xinfinance.com/html/OBAOR/

Source: http://en.xinfinance.com/html/OBAOR/

The orange dots in the figure depict the land route while the blue dots denote sea route. The land route, as evident is very inclusive. Beginning from China, crossing Central Asia, Russia and entering Eastern Europe, it finally finds its way to core Europe. Thus, it is but natural that China is likely to play safe while dealing with Europe and Russia.

That Xi Jinping is very serious about realising his Chinese dream is also clear from the efforts China has been making lately in reaching out to Europe. To take the latest example, soon after victory day celebrations in Moscow, Xi Jinping travelled to Belarus where he and his Belarus counterpart, President Alexander Lukashenko signed a treaty of friendship and cooperation with both sides agreeing to cooperate "to preserve and strengthen peace and stability in Eurasia, to turn the region into a zone of peace, security and sustainable development, joint well-being, and harmony"("Belarus China Sign Treaty" 2015). Eastern Europe being the gateway to mainland Europe, Xi Jinping has begun to show greater visibility in the region.

The current geopolitical scenario has worked in China’s favour, considering the pace at which Beijing is carrying out its projects. The creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank(AIIB) is important in this regard as it is seen as an avenue to finance the infrastructure projects that will make up the "belt and road." Things have largely turned in Beijing’s favour as evident from the support it has received for the AIIB.

Conclusion

Xi Jinping’s foreign policy gives acute emphasis to the development of silk roads. Hence, it is not surprising that China has an upper hand in influencing economic and political might in the Central Asian region. The closer Moscow and Beijing get, the more Russia will have to adjust to China’s interests. It is important to understand that while Moscow depends heavily on Beijing, the situation is not true in the reverse. Russia’s renewed thrust to China is driven by its desire to diversify its economy. However, in the process of diversification, it is increasingly adhering to the latter’s needs.

One cannot ignore the fact that profound disparities in bilateral economic cooperation exist between China and Russia which is highly unfavourable for the latter. Russia’s exports to China largely comprise primary material (oil, coal, wood and gold). On the other hand, it imports manufacturing products (machinery and transport equipment). This arrangement is reminiscent of the colonial set-up that characterised the 20th century. This set-up, if continued, will expand China’s influence in the Russian market and turn Russia into a junior ally. This again is very ironical because Moscow has refused a subordinate relationship with Washington, but is moving in the same direction with China.

References

"Belarus, China Sign Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation" (2015): Belarusian News, 10 May, http://eng.belta.by/all_news/president/Belarus-China-sign-treaty-of-friendship-and-cooperation_i_81632.html.

Brown, Stephen and Ankita Breidthardt (2014): "China Takes No Sides on Ukraine Crisis, Xi Tells Europe," Reuters, 28 March, http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/28/us-ukraine-china-germany-idUSBREA2R1HC20140328.

Eckel, Mike (2014): "China May Be Biggest Winner from Ukraine Crisis," Voice of America, 1 September, http://www.voanews.com/content/china-ukraine-russia-benefits/2432373.html.

Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of India (2015): "President Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin of Russia Meets with Wang Yi," 8 April, http://in.china-embassy.org/eng/zgxw/t1253304.htm.

Lim, Louisa (2013): "Chasing the Chinese Dream - If You Can Define It," National Public Radio, 29 April, http://www.npr.org/2013/04/29/179838801/chasing-the-chinese-dream-if-you-can-define-it?sc=tw&cc=share.

Perlez, Jane (2015): "As Russia Remembers War in Europe, Guest of Honor Is From China," New York Times, 8 May, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/09/world/asia/as-russia-remembers-war-in-europe-guest-of-honor-is-from-china.html.

Porter, Tom (2015): "Russia and China Strengthen Ties, as Putin Looks East in Wake of Western Sanctions,"International Business Times, 8 March, http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/russia-china-strengthen-ties-putin-looks-east-wake-western-sanctions-1490985.

(The writer is a Research Assistant with Observer Research Foundation, Delhi)

Courtesy: Economic and Political Weekly

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV