-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

This is the fourteenth paper in National Security series

Read all the papers here.

The state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) has witnessed various phases of conflict since 1989, when massive violations of civil liberties, and a sense of both deprivation and being abandoned by New Delhi, gave birth to militancy in the Valley. Pakistan then seized the opportunity to wage a proxy war against India, which is still going on. The second phase of unrest was ignited in 2008 over the Amarnath Land row,[i] and the third in 2010, by the Machil encounter[ii] and the killing by the police of Tufail Ashraf Mattoo, an innocent teenager.

Following the killing in July 2016 of Burhan Wani—the widely popular commander of the Kashmiri militant group, Hizbul Mujahideen—the conflict seemed to have entered a new phase. Radicalisation has made deep inroads into society, eroding the communal and social harmony that for a long time characterised the Valley’s Kashmiriyat (or ‘identity’). As this brief will show, today, the youth in the Valley are overwhelmed by a deep sense of alienation.

This brief presents the findings of a survey conducted by the author among the youth of J&K. The survey tried to quantify the reasons for the aggravated “Conflict in Kashmir”,[iii] and involved freewheeling discussions with the respondents to get a better understanding of the perceptions of the youth about the worsening situation in the Valley in the past three years.

It was in these last three years that Pakistan-supported insurgency in J&K assumed an ‘autonomy’, driven by more emotive issues that are different from those that had given birth to the secessionist movement. This new form of insurgency departs from the secessionist politics of the Hurriyat and veering in a more dangerous direction, primarily because of the failure of the government to comprehend and respond effectively to two recent phenomena: the lowering of the age profile of the new generation of militants; and the lack of control of the older generation of secessionist leaders over them.

Indeed, policymakers in New Delhi appear unwilling to shed their old paradigms; they continue to regard the current wave of violence in the Valley as being caused primarily by Pakistan’s proxy war and meddling in Kashmir. While it is undeniable that Pakistan will continue to take advantage of the turmoil in Kashmir to stoke the insurgency, New Delhi will have to look beyond the ‘proxy war’ to understand why boys – in ever larger numbers – are taking to violence.

Seeing the Kashmir conflict only through the Pakistani lens has failed to lead policymakers to a proper understanding of the issues, much less to a resolution. For Kashmiris, New Delhi’s approach to their woes has always focused on personalities rather than people. The interventions that New Delhi has made have been through either appeasement of the local political elite or else, the use of excessive force. The policy of unconditional appeasement of regional political leaders by a succession of governments at the Centre has created vested interests, trapping the Valley in an unending cycle of bad governance and corruption. New Delhi’s perceptible silence and apathy towards the people of the state, especially when the J&K has earned a dubious distinction of being the most corrupt state in India,[iv] has further eroded the confidence of the Valley’s youth in New Delhi.

As this brief will show, the gulf between (mainland) India and the people of Kashmir, especially the young and educated, is now wider than ever before. The problem is not only that of stone-pelting protesters. The problem is deeper: of perceptions and ideologies that have been heavily influenced by radical forces. The threat perception among the Kashmiris has increased as they feel that New Delhi has been nonchalant, especially after the shelving of the interlocutor’s report of 2010.[v] The looming threat of erosion of Article 35A and the Article 370 coming under severe criticism from the right-wing fringe has also dented the confidence of the people.[vi]

The growing radicalisation reminds us of the great Kalhana who wrote in Rajatarangni, “Kashmir can be won by Power of Sprit (love) … but not by power of Sword (force)”. Kalhana’s philosophy, written in Sanskrit verse in the 12th century, begs to be understood in its true sense today, more than ever before.

In July 2017, ORF organised “Kashmir a Dialogue for Peace and Integration”, a multi-stakeholder conference in Mumbai. The conference was attended by experts from Kashmir and across India including bureaucrats, former armed forces officials, regional political leaders, scholars, Kashmiri Pandits, leaders of Kashmir’s traders’ associations, and journalists. The participants discussed the Kashmir problem and covered a wide range of issues including Kashmiriyat, radicalisation, governance, socio-economics, the role of the media, and Article 370. The conference did not aim to reach a consensus on any of the issues that have radically transformed the nature of the ‘Conflict in Kashmir’. These issues are significant as they have changed – and continue to change – the perceptions of the Kashmiri people towards India. These perceptions are exploited by the political elites both within the state and in the rest of India, further escalating the problem.

To assess the feedback gained from the conference and build on these variables, this author undertook a comprehensive survey covering the most disturbed areas in the Valley. The questionnaire was developed in close consultation with some of the experts who participated in the conference. The survey, carried out from September to November 2017, used snowball sampling[vii] in different colleges and universities of Kashmir (University of Kashmir, Islamic University of Science and Technology, Awantipora, and Central University, Nowgam) involving a cross-section of the students and the faculty. The respondents comprised both male and female, and were between the ages of 16 and 30.

Nearly 2,300 responses were recorded. To obtain in-depth baseline data for the study, the questionnaire covered political, social, economic, cultural and religious dimensions of the following core topics:

The responses to the questions were tabulated and analysed with great care. The following sections discuss the findings of the survey.

For centuries, Muslims and pandits (Hindus living in Kashmir) shared a common culture and co-existed peacefully in the Valley. The common cultural milieu, which is called Kashmiriyat, defined the unique confluence of Hinduism and Islam—a weaving of their rich cultural and religious practices that brought to life a uniquely syncretic devotional and philosophical “Kashmiri” way of life.

After 1989, the radicalisation of a section of Muslims resulted in the selective killings of pandits, especially of those working for the government, forcing those who survived the violence to flee the Valley. The exodus shattered the centuries-old harmony between the two communities. Since then, most Kashmiri Muslims have not opposed the idea of a return of the pandits to their homeland, even as the issue is caught up in the crosshairs of debates on the history and politics of their forced migration. The last four years of amplified discourse on Kashmiriyat—set against the backdrop of increased communalisation in the Valley—has vitiated the socio-political environment that earlier seemed to open up to inter-communal reconciliation. The very essence of Kashmiriyat is under threat.

The young generation of Kashmiris who grew up in an era of violence is largely ignorant of the true meaning of Kashmiriyat, having been raised instead in the binary ideology of “Us versus Them”. Secondly, a dominant and vocal section of the pandits, after migration, came to be identified with ultra-right-wing organisations that similarly de-emphasised the Kashmiriyat component of their identity. For their part, the Kashmiri Muslims stressed more on their “Islamic” identity rather than on their “Kashmiri” identity; they saw themselves as part of a global Islamic community.

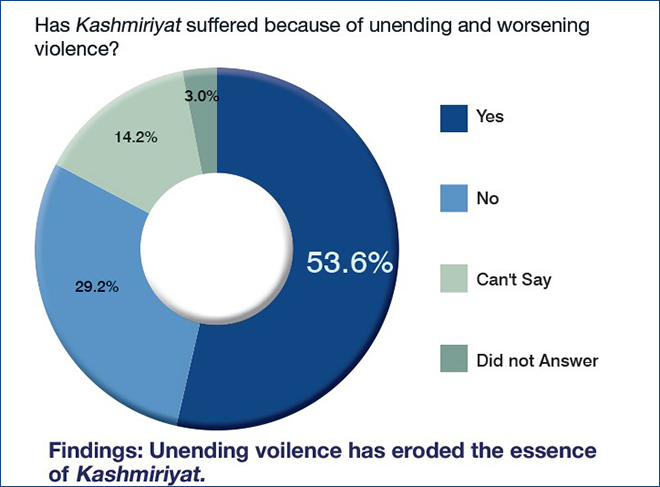

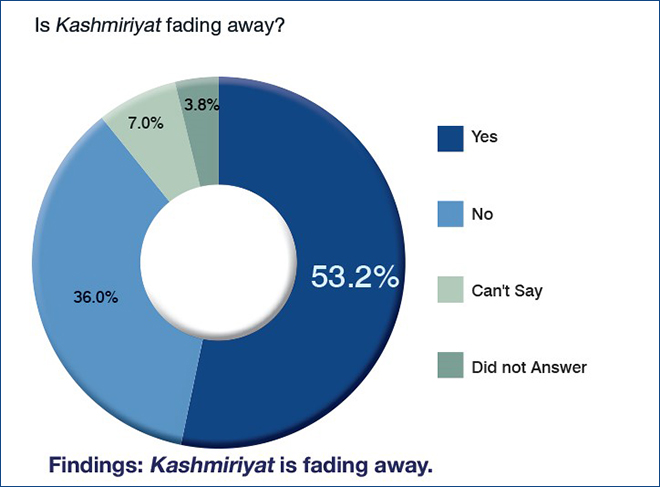

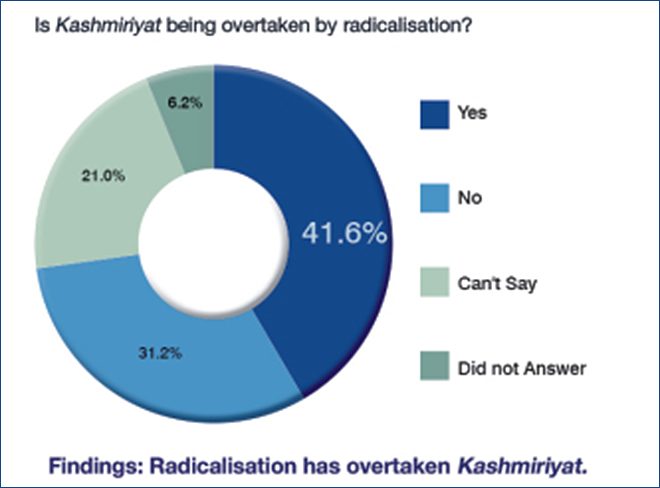

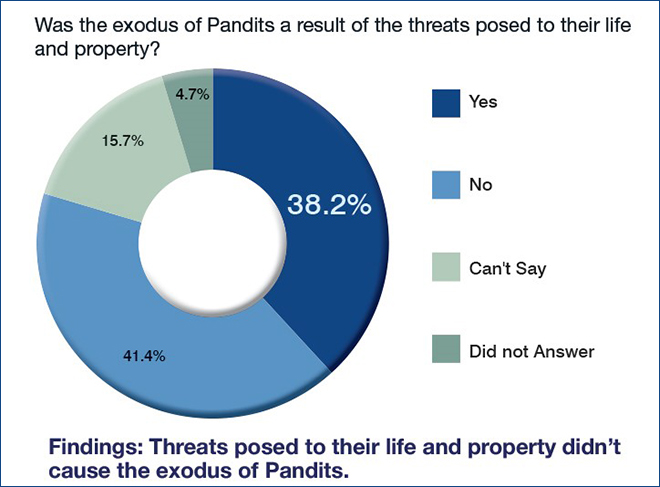

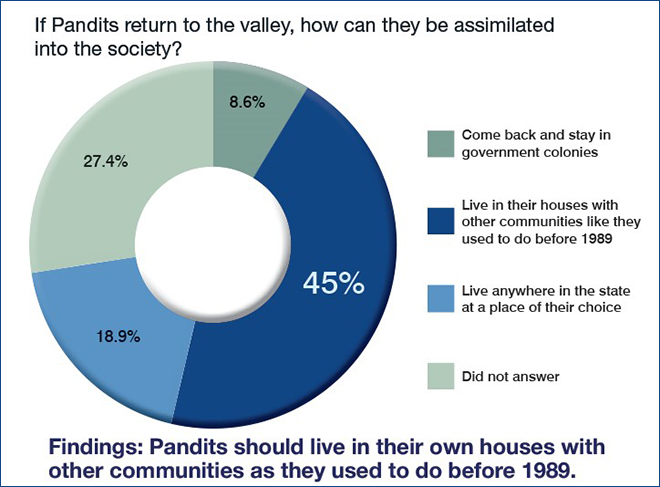

Figures 1a, b, c, d, e: Graphical representation of ORF survey results on the essence of Kashmiriyat, as well as other related questions.

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1c

Fig. 1d

Fig. 1e

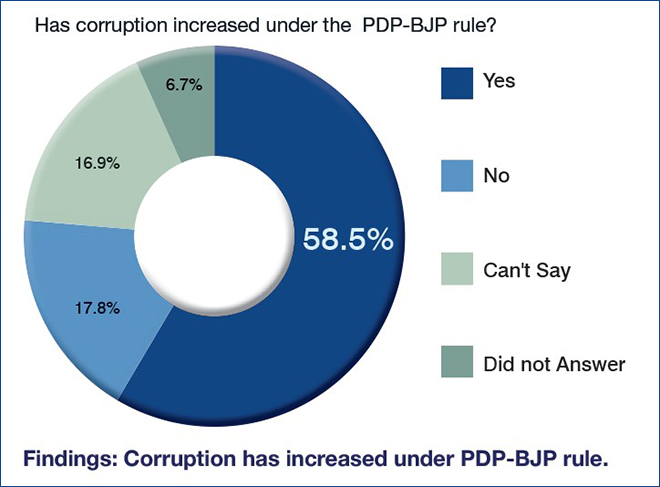

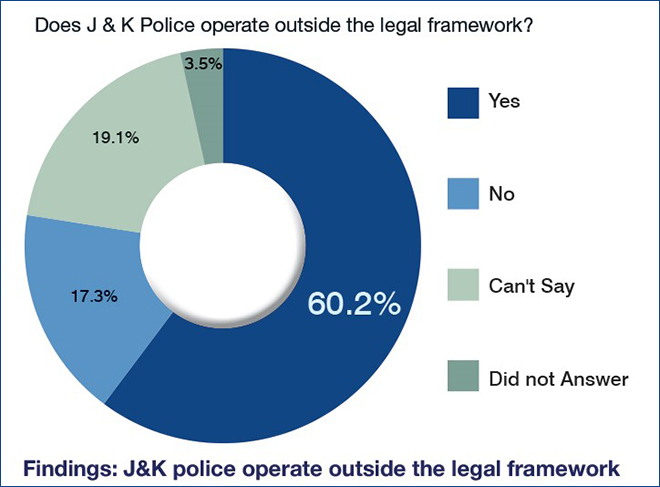

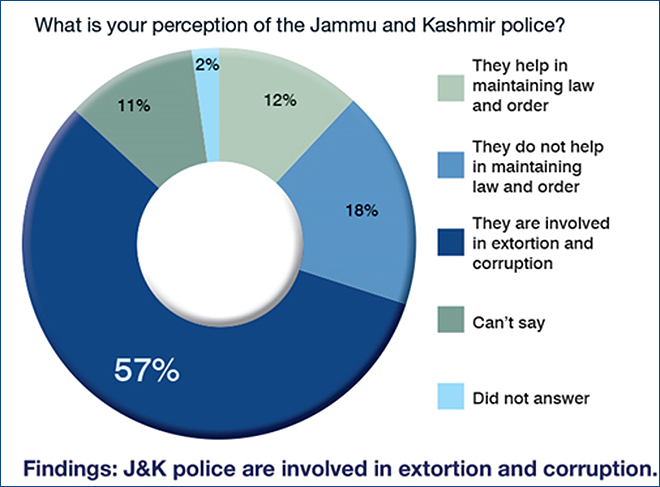

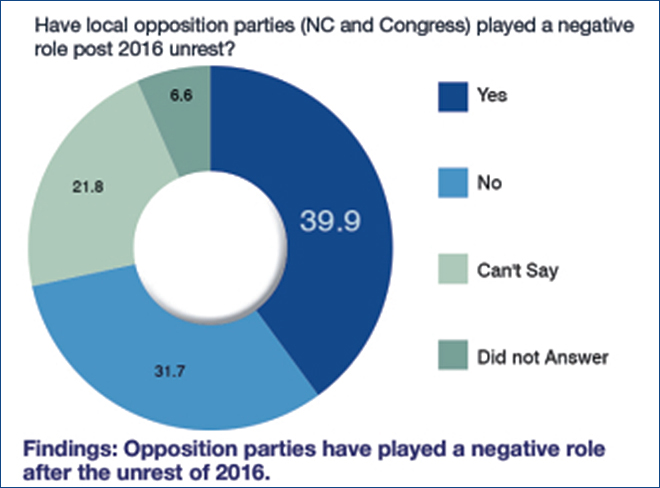

Since 1947, misgovernance and poor administration have been the biggest problems of the state of J&K, fuelling the alienation of the youth from the government at the Centre and pushing them to the side of radical elements. The youth of Kashmir are no longer willing to tolerate corruption, inequality and nepotism.

Three decades ago, the insurgency was indigenous and primarily targeted the corrupt governance and autocratic rule of Sheikh Abdullah. Pakistan, with the help of some local vested interests, used the situation to further agitate the youth who were already being denied their civil liberties, to begin with. New Delhi’s policy of appeasement is also to be blamed. The Centre has turned a blind eye to the misdeeds of the state, denying the people of the Valley their right to an accountable government. Some analysts say that “rampant corruption, with officials looting the exchequer at will; and Mafia-style authoritarianism, marked by the use of police and gangs of professional thugs against any sign of opposition” became the norm in the state.[viii]

The CMS-India Corruption Study 2017 ranked J&K among the most corrupt states in India. It revealed that 84 percent of the people surveyed perceived increased corruption in public services. The state has for long been also accused of financial irregularities, including misusing grants from the centre. J&K received INR 1.14 lakh crore (10 percent) of all Central grants given to states over the period 2000-2016, despite having only one percent of the country’s population. That means Jammu and Kashmir, with a population of 12.55 million according to the 2011 Census, received INR 91,300 per person, while Uttar Pradesh, the country’s most populous state (with 190 million), received INR 4,300 per person over the same period. The government has also been repeatedly criticised by CAG for "serious financial irregularities".[ix]

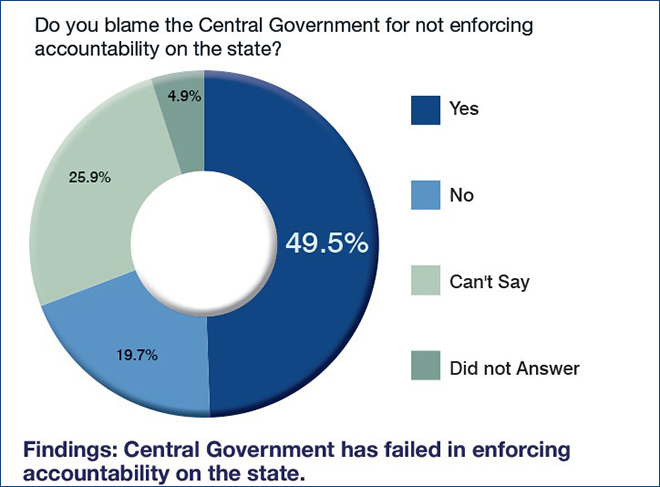

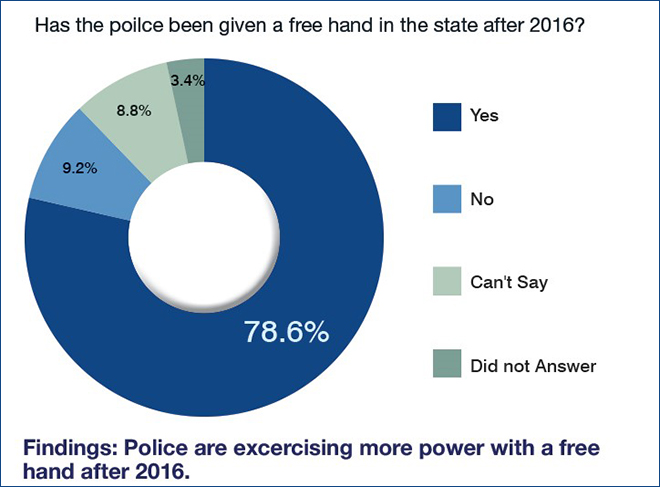

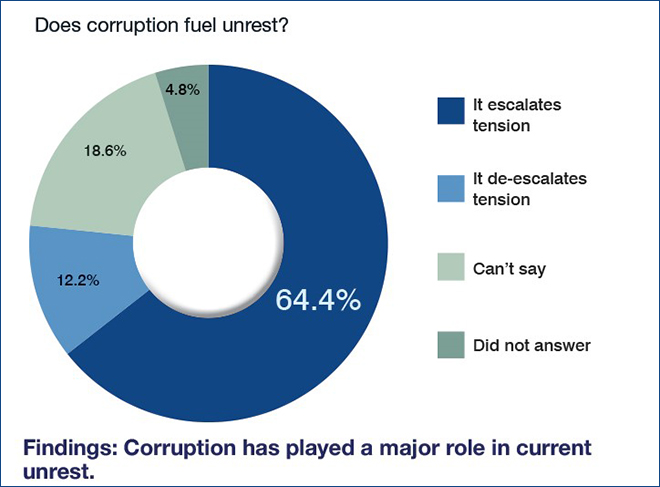

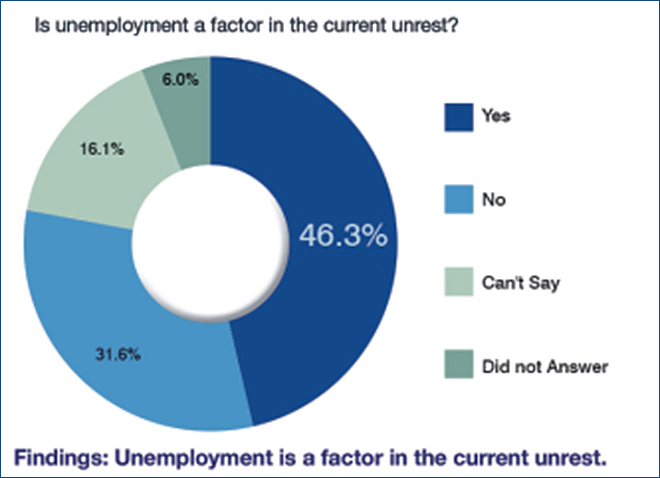

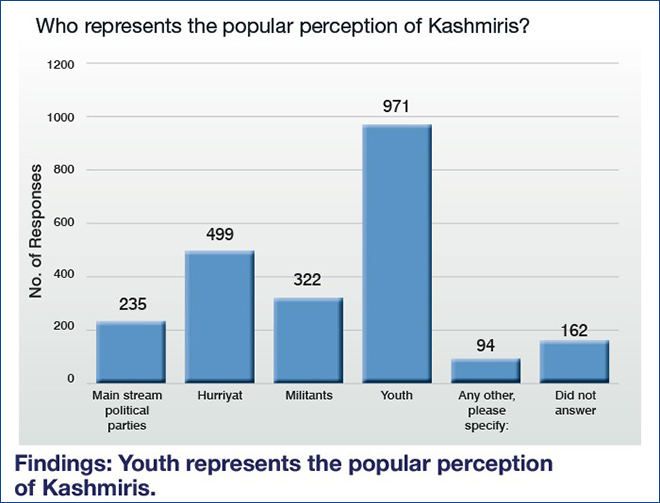

Figures 2a, b, c, d, e, f: Graphical representation of ORF survey results on misgovernance, nepotism, corruption, and rule of law.

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2b

Fig. 2c

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2e

Fig. 2f

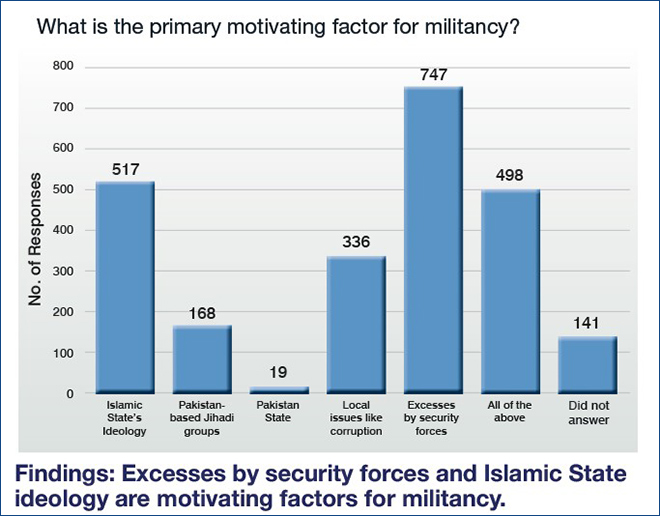

Following the unrest of 2016, the number of local boys joining militancy has increased at an alarming pace: the number reached 88 in 2016, and further increased to 126 in 2017. According to official data, more than 300 militants are active in Kashmir for the first time in 10 years.[x] The Deccan Herald has also reported that in the first six months of 2018 alone, 82 boys joined militancy. Support for the militant groups has also been expanding.[xi]

The number of civilians getting killed in the conflict is also rising. According to official data, in the last 18 months alone, 106 civilians were killed at encounter sites during Cordon and Search Operations (CASO) of the security forces as protesters tried to get closer to where militants were holed up by resorting to stone pelting.

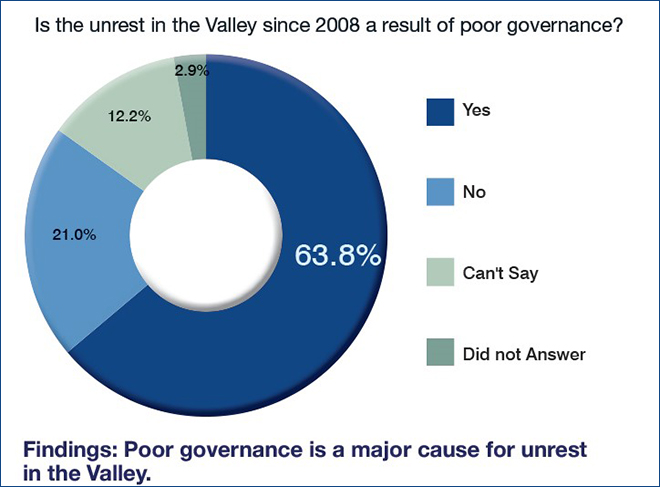

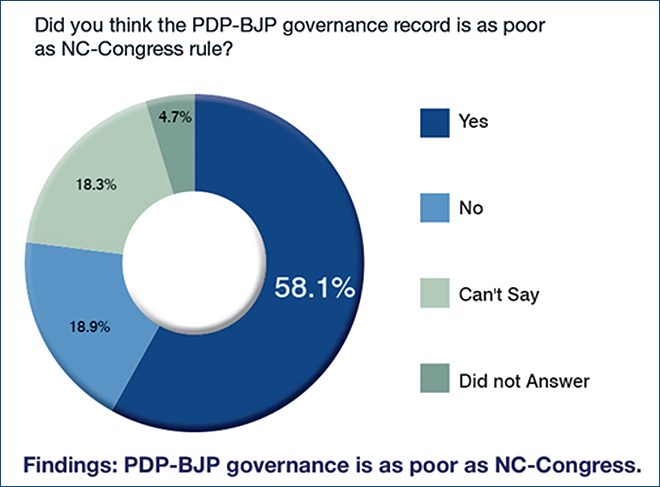

Figures 3a, b, c,d, e, f: Graphical representation of ORF survey results on the growing unrest and violent militancy.

Fig. 3a

Fig. 3b

Fig. 3c

Fig. 3d

Fig. 3e

Fig. 3f

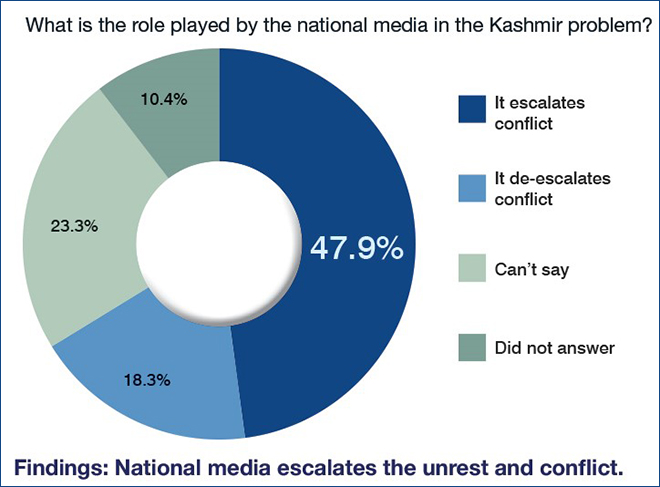

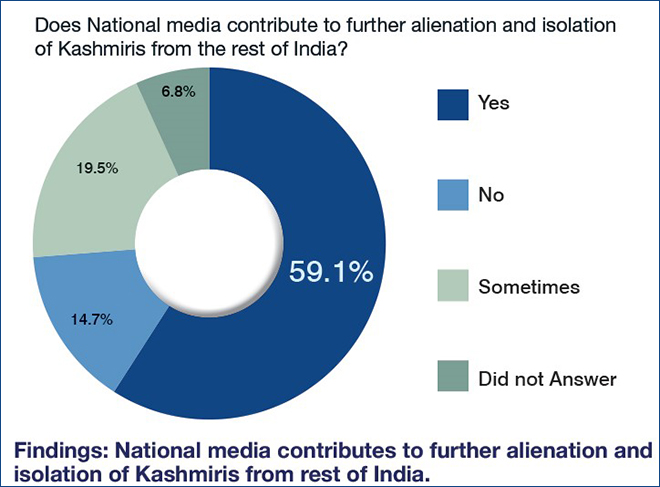

The media, whether electronic, print or social—and at the national as well as local level—have played a crucial role in managing the people’s perceptions both within the Valley and across the country. Constant high-decibel media rhetoric and the spread of radicalisation through social media have further fuelled unrest in Kashmir.[xii] The national media has demonised Kashmiris by labelling them as “Pakistani agents” or “terrorists”. They have failed to adequately highlight issues such as the excessive use of force by the state forces. For TRPs, the media have widened the rift between the Kashmiri youth and the rest of the Indian people, in the process inadvertently playing into the hands of Pakistan: the more anti-Kashmiri stories are published, the more pro-Pakistan sentiments are fuelled, and the stronger is the sense of alienation from the rest of India.[xiii]

The mainstream media both at national and regional levels have failed to accord serious attention to the core issues involving the denial of basic rights to Kashmiris, which have long been taken for granted by Indians in other parts of the country. Irresponsible 24x7 media coverage has created a gulf not only between New Delhi and common Kashmiris, but also between the people of Kashmir and the masses of India. The perception created by the media has made young Kashmiris studying or working outside the Valley vulnerable to livid name-calling—”terrorists”, “Pakistanis”; in some instances, they have fallen victim to violence.[xiv]

Figures 4a, b: Graphical representation of ORF survey results on the role of the media in Kashmir’s unrest.

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4b

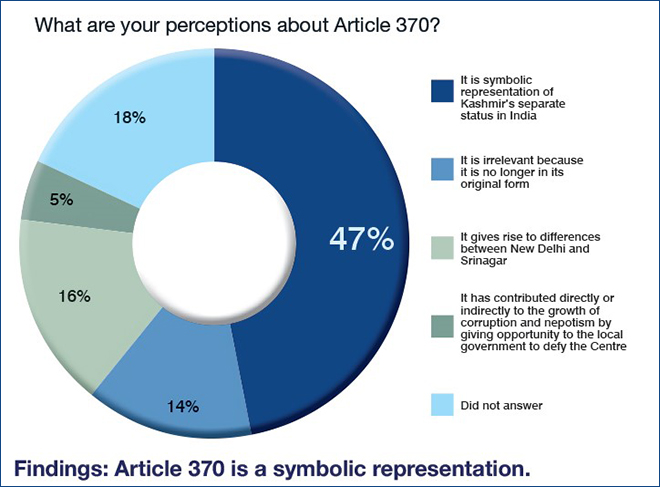

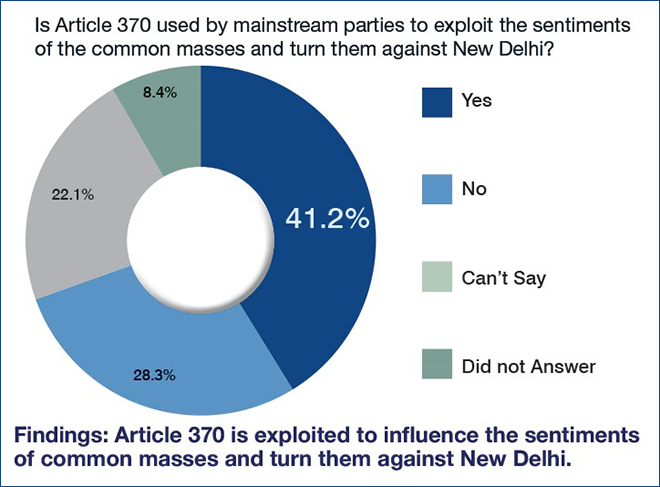

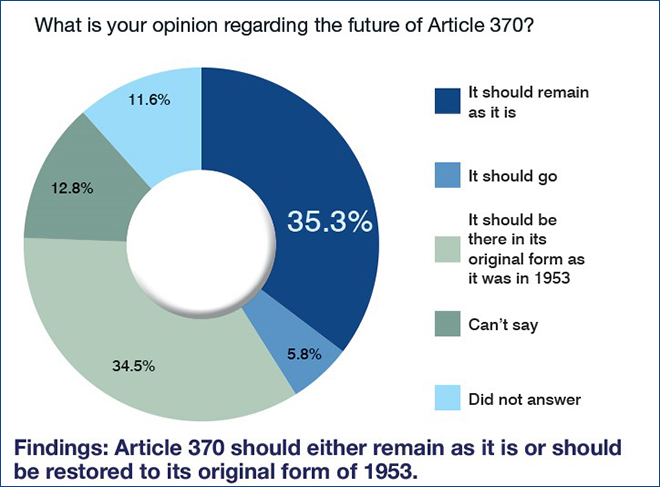

Article 370 of the Constitution of India gives autonomy to the state of J&K within the Union of India. Autonomy or self-rule empowers the state government to address governance and administrative challenges and weaknesses with a greater degree of self-determination. The spirit of autonomy dictates that since decision-making is a local process, there is a greater probability that the locally-formulated government programmes will cater to the particular needs of the local community. Autonomy also gives the local community the opportunity to make their leaders accountable.

Most of this author’s respondents think of autonomy as the main mechanism to resolve tensions and redistributive issues between the Central Government and spatially-concentrated, culturally-distinct groups of Kashmir and Ladakh”. On the other hand, most politicians at the centre, as well as scholars, are of the opinion that autonomy whets secessionist appetites and inflames the relations between the Centre and local government as the Kashmiris desire for separatism. On various occasions, Article 370 (granting autonomy to J&K) was eroded by the Centre with the consent of local politicians for the purpose of national integration and assimilation of the country’s only Muslim-dominated state with the rest of India. In recent years, Article 370 has once again become the centre of acrimonious discussions across India. The manifesto of the BJP in the 2014 Lok Sabha election stated that it remained committed to the “abrogation” of Article 370.[xv] However, once BJP formed its alliance with the PDP (regional party) in 2015 to rule J&K and signed the ‘Agenda of Alliance’ “whilst recognising the different positions of the parties [on Article 370], all the constitutional provisions pertaining to Kashmir including the special status” were kept intact. Furthermore, there was a petition filed by ‘We the Citizens,’ a Delhi-based NGO in 2014 in the Supreme Court against Article 35A of the Indian Constitution. Article 35A empowers the state legislature to define “Permanent Residents” of the state.

Figures 5a, b, c: Graphical representation of ORF survey results on the contentious issues of Article 370 and Article 35A.

Fig. 5a

Fig. 5b

Fig. 5c

ORF expresses its gratitude to the participants in the day-long roundtable held on 7 July 2017 in Mumbai. Their insights have helped in this research. The author would also like to pay tribute to Shujaat Bukhari, editor of Rising Kashmir, who was recently killed by terrorists for his involvement in peace efforts.

The author is grateful to the people of Kashmir who helped ORF during the field surveys in conflict-hit districts. The teachers, professors, students, business people and shopkeepers, who patiently responded to the questionnaires and gave their precious time for interviews. The questionnaire took more than two hours to complete, but the devotion of the respondents showed their desire for peace and normalcy in their lives.

The author also thanks Sufia Nadeem, Pravin C and Aditya Thorat, interns at ORF Mumbai, who segregated and compiled the data from 2,300 respondents for nearly two months and cross-checked each other’s data to ensure that the findings were unbiased. A special thanks to Ameya Pimpalkhare, Associate Fellow at ORF in Mumbai, not only for his help in the data-crunching, but also his suggestions on the research.

Sushant Sareen (Senior Fellow, ORF) and Dr Ashok K. Behuria (Coordinator, South Asia Centre, IDSA, New Delhi), constantly gave encouragement, and Dhaval D Desai (Vice President, ORF Mumbai), not only took special interest in the project, but gave precious time to encourage this author. This project would not have been completed without his help.

[i] On 26 May 2008, J&K state government and Government of India signed an agreement diverting land (39.88 hectares) to Shri Amarnath Shrine Board (SASB) via order number 184-FST of 2008. The land was to be used to make temporary shelters and other facilities for Amaranth pilgrims. However, the people of Kashmir protested, and within days, the action snowballed into one of the biggest pro-independence demonstrations in Muslim-majority Kashmir since insurgency broke out in 1989. More than 38 people were killed and 1,000 injured in the protests over 64 days, forcing the government to backtrack. However, the situation took a communal turn and ripped through the old secular relations between Jammu and Kashmir provinces of the state. Hindus in Jammu, angered by the government’s U-turn, attacked lorries carrying supplies to the Kashmir Valley and blocked the region’s highway. Challenging the blockade, Muslims took to the streets in Kashmir and clashed with police as separatists united to launch some of the biggest pro-independence demonstrations in Kashmir;

[ii] The infamous Machil “encounter” in 2010, in which three men were killed, was a tipping point for the Kashmir unrest; the ensuing violence left 120 people dead. The army personnel who were involved in the incident claimed that the killings were a result of an armed encounter with terrorists in Machil, close to the LoC, in Kupwara district. A police enquiry, however, concluded that Machil was a staged encounter and all three civilians who were killed were innocent labourers from Nadihal, in Rafiabad. The army court, too, confirmed that the encounter had been simply orchestrated. Five personnel, including one with a rank of Colonel, were sentenced to life imprisonment. The memories of Machil resurfaced in July 2017 when the Armed Forces Tribunal in Chandigarh suspended the sentence on dubious grounds and the five convicts walked free. Though the Army laws are harsh and strictly implemented, arbitrary leniency shown toward delinquent officers, as in the case of the convicted personnel in the Machil fake encounter, has further amplified the demand for the revocation of the AFPSA. The tragic episode was not because of excesses committed under the AFSPA, but a criminal act by an officer for his own vested interests that was twisted to portray the armed forces and its tool, the AFSPA, as draconian: Ayjaz Wani & Dhaval D. Desai, “The road to peace in Kashmir: Public perception of the contentious AFSPA and PSA”, Observer Research Foundation, Occasional Paper 164, Aug 16, 2018.

[iii] This brief defines “conflict in Kashmir” as the growing alienation, corruption, alleged human rights violations and other unsettling events that trigger unrest in Kashmir in form of protests, stone pelting, and the rising number of homegrown insurgents. The parties in the “conflict in Kashmir” are the people of Kashmir and New Delhi who can together resolve the issues within the ambit of the Constitution of India. With the help of a section of the Kashmiri society, Pakistan succeeded in making the conflict in Kashmir into the seemingly unending phenomenon that it now is. Over time, these internal dynamics have worked to make the “conflict in Kashmir” – a highly nuanced result of the government’s botched up policies – directly proportional to the “conflict over Kashmir”, one that is a consequence of the unresolved legacy issues between India and Pakistan. The “conflict over Kashmir” is between India and Pakistan over the disputed area of Kashmir that started after the invasion of Pakistani army in October 1947. Whenever the ‘conflict in Kashmir’ has escalated, the ‘conflict over Kashmir’ has also intensified. For example, from 2016, ceasefire violations (CFVs) – used by Pakistan to provide cover to infiltrators into J&K across the Line of Control (LoC) – have increased enormously in tandem with the escalation of insurgency in Kashmir.

[iv] CMS-India Corruption Study 2017, Perception and Experience with Public Services & Snapshot View for 2005-17, (CMC Research house, Saket Community Centre, New Delhi, 2017)

[v] The central government appointed the J&K Interlocutors Group on October 13, 2010 after the revolt. The members of the group were Radha Kumar, M.M. Ansari and Dileep Padgaonkar (chairman). The contents of this report were primarily the outcome of the Group’s interactions with more than 700 delegations held in all the 22 districts of J & K and the three roundtable conferences organised by the State and Union government since October 2010. Furthermore, the members met several thousand ordinary citizens who turned up during the three mass meetings to express their views on a wide range of issues. The members of the team also met militants and stone-pelters lodged in the Central Jail in Srinagar, and the families of the victims of alleged human rights abuses. The Group submitted its report to the Home Ministry and was made public by on 24 May 2012. However, no progress was made on the recommendations and comments by the government. Radha Kumar, M.M. Ansari, Dileep Padgaonkar, “A New Compact with the People of Jammu and Kashmir, Group of Interlocutors for J&K, Final Report”

[vi] A writ petition filed by NGO “We the Citizens challenges” the validity of both Article 35A and Article 370 with an argument that Article 370 was only a ‘temporary provision’ to help bring normalcy in State and strengthen democracy in that State, it contends. The Constitution-makers did not intend Article 370 to be a tool to bring permanent amendments, like Article 35A, in the Constitution. According to the petition, Article 35A is against the “very spirit of oneness of India” as it creates a “class within a class of Indian citizens”. Restricting citizens from other States from getting employment or buying property within Jammu and Kashmir is a violation of fundamental rights under Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution. Most of the respondents argue that the petition in Supreme Court is nothing but the agenda of RSS-based ideologies and has dented the aspirations of the people in Kashmir.

[vii] In conflict environments, the population is marginalised to some degree, making it ‘hidden’ from and ‘hard to reach’ for the researcher. The marginalisation explains why it is difficult to locate, access and enlist the cooperation of the research populations, which, in a nonconflict context, would not have been difficult to do. The Snowball Sampling Method (SSM) is used to address the fears and mistrust common to the conflict environment and increases the facilitates an atmosphere of trust as the researcher is introduced through a reliable social network. For this study, the social network was provided by teachers of different colleges, Universities and academic institutions that helped the researcher generate a friendly and trustworthy environment. In some cases, SSM marks the difference between research conducted under constrained conditions and research not conducted at all.

[viii] Sumantra Bose, Kashmir: Roots of Conflict Paths to Peace (London; Harvard University Press, 2003); Navnita Chadha Behera, Demystifying Kashmir (Washington D.C: Brookings Institution Press,2006). During the field visits to Kashmir, even a layman asks the question of what New Delhi has done for the betterment of administration in the state.

[ix] Ayjaz Wani , Dhaval Desai, “Centre must step in to end corruption in Kashmir”, Observer Research Foundation, March 9, 2018

[x] Number of listed militants crosses 300 in Kashmir for first time in 10 years: Report: Greater Kashmir, September 29, 2018.

[xi] Most of the respondents argued, giving different reasons. The insurgents or homegrown terrorists are seen as heroes. Most of the homegrown insurgents use social media platforms to express their views, and these pages are being viewed thousands of times by local youth. An article written by scholar-turned-militant/terrorist Manan Wani was published by a local news agency on July 16, 2018, “Why did he choose Gun over Pen?”. The article was circulated on social media thousands of times. Wani would accuse New Delhi of “saffronising” every inch of India. The influence of militants/terrorists has also increased manifold on society in general and youth in particular. For example, in South Kashmir’s Pulwama district, most of the drug-peddlers were recently tortured by the militants and their pictures were circulated on social media. Most of the youth interviewed by the researcher asked, “When the work of the state is being done by the militants, why should they not be revered?” For example, Rashid Billa, a wanted pro-government gunman, was killed by militants in 2017. He was wanted in many cases and was evading arrest. The respondents held that the people “have lost faith in the state apparatus and are more inclined towards militants and insurgents.”

[xii] The respondents, during the survey, always argued that the social media and national news channels helped in the alienation of Kashmiris from mainland India. Kashmiris have a sense of fear and mistrust in their interaction with Indians in other parts of the country, which has inhibited the steady and free movement of Kashmiris for study or employment. Vitriolic media reports have created an anti-Kashmiri perception in the rest of India. The pervasive sense of alienation in Kashmir and the deep sense of mistrust about Kashmiris in the rest of India feed off each other.

[xiii] Discussions with the respondents.

[xiv] Most of the respondents, especially students, when asked if they would like to go to school or find jobs in other places in India, said that as Kashmiris, it is difficult for them to find a job, or even find accommodation. They said that the general perception about them that they are “terrorists” or “Pakistan agents”.

[xv] BJP Election Manifesto 2014 highlights

[xvi] Arguments of teachers and students of Law department, University of Kashmir.

[xvii] Behra op.cit. The 2014 elections were directly contested on these lines and has now brought a setback in the relations between Jammu province and Kashmir province.

[xviii] Ayjaz Wani op. cit.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ayjaz Wani (Phd) is a Fellow in the Strategic Studies Programme at ORF. Based out of Mumbai, he tracks China’s relations with Central Asia, Pakistan and ...

Read More +