-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The latest attack in Pathankot on the night of January 1 and 2 is one more terror incident in a long series where every attempt by India to improve relations has evoked this kind of a response.

Everyone knows the list -- The Lahore Bus Yatra followed/accompanied by Kargil in 1999.

When the Agra Summit failed in 2001, we had the Parliament attack in December. When Indian forces were deployed in response, we had the attack on Kalu Chak in May 2002 and the two countries almost went to war.

After the Musharraf-Manmohan talks ran into rough weather and Musharraf concluded he was not going to get what he wanted, we had the Mumbai serial train bombings and again Mumbai 2008.

The prime ministers met in Ufa last July and the response was a terrorist attack in Gurdaspur.

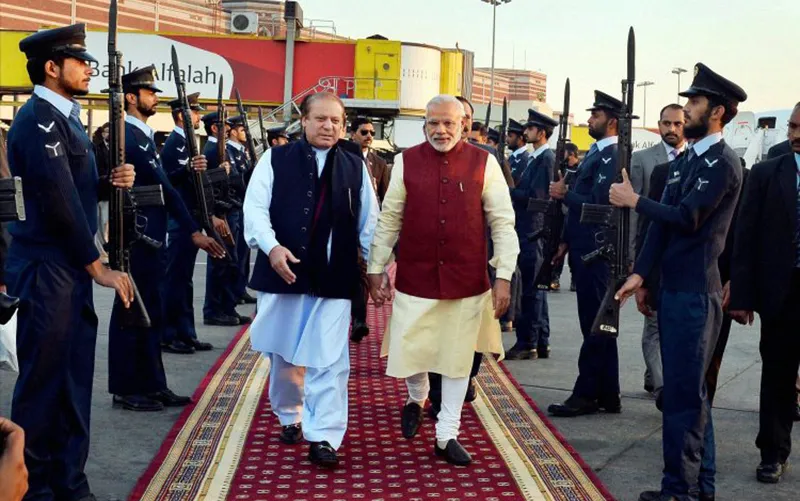

The Pathankot attack was less than a week after Prime Minister Narendra Modi met his counterpart in Lahore. Terrorists were able to penetrate the outer perimeter despite advance intelligence and massive security deployed in anticipation.

This prevented a massive attack on the main base although the ease with which they reached the target despite the warning is disturbing. They commandeered a vehicle and knew exactly where to go.

This means they had reconnoitered the airbase, worked out entry and exit points and they had local assistance. Some resident sleepers would have helped them to get to their target 30 kilometres away from the border in the middle of the night.

Punjab has been the target in recent months and the latest penetration at the Bhatinda air base, a classic intelligence operation, indicates heightened espionage efforts. There may be other similar operations and it remains to be seen if the Indian Air Force is being specially targeted.

Plus ca change, plus c'est la meme chose -- the more things change, the more they remain the same. This is what describes Pakistan's attitude towards India.

Yet there are many in India and some in Pakistan who are unable or unwilling to see the reality of India-Pakistan relations.

This category in India has unrealistic hopes that peace and normalcy is round the corner while there are many in Pakistan that their policy of terror and forcing India to talk under duress is succeeding. The formula is 'terror till you talk' and 'terror again if you stop talking.'

Meanwhile, the strategy is to frighten the West of a low Pakistani nuclear threshold where the nuclear weapon is not just a deterrent against, but actually usable against India while indulging in terror in India.

The game is to spread terror periodically in India and scare the rest of the world that a nuclear war is a distinct possibility if India reacts with force if Pakistan were to cross red lines.

From time to time, we in India go through this great melodrama after Indian and Pakistani leaders meet, by accident, design or surprise. It then becomes a given amongst strategists and, of course, the media and the Candlelight Brigade to collectively exult about the peace that they think is about to break out.

Now that Modiji has gone and surprised half the world with his lunch in Lahore and some have either cheered enthusiastically or others condemned this giving their own spin, it is time to sit back and reflect a little on what this latest high drama means.

First, the obvious observation is that the visit was carefully choreographed and every aspect worked out. Final touches were presumably given to all this when the two NSAs met in Bangkok, which meant that the Pakistan army was on board with this.

Modi and Nawaz Sharif are not exactly buddies that one could call the other at the last minute, and ask if the other was free for an impromptu lunch. Surely, Modi would not run the risk of being snubbed by Nawaz nor could have Sharif have invited Modi to drop by without a say so from GHQ Rawalpindi.

Tentative preparations for such a meeting may have begun in Kathmandu, but official disclosure would have got the political opposition and the media in India ablaze with similar reactions in Pakistan.

The disclosure by an Indian industrialist, who is said to have arranged a one-hour secret meeting between Sharif and Modi during the last SAARC meeting in Kathmandu, was the better way of testing the waters.

There was hardly any reaction to this in both capitals, and if at all, it was positive. There was no reprimand to the industrialist who then showed up when the two PMs met in Lahore. Was this a coincidence? Probably not.

Modi had probably set the red lines after extending the hand of friendship in May 2014 at the time of his swearing-in; this was that India would respond with massive force to any cross-LoC firing or infiltration by terrorists. Also, that past policies notwithstanding, India would frown at any high-profile meeting with the Hurriyat by Pakistanis prior to any bilateral talks.

Ufa was seen by the Indians as having scored over Nawaz as we got him to say yes to talks on terror without a reference to Kashmir. This was followed by exaggerated triumphalism in India and the Pakistan army must have been livid and Nawaz embarrassed.

Presumably Nawaz and Modi realised that any forward movement would need below the radar meetings and the Pakistan army has to be involved.

An army general as Pakistan's NSA instead of a civilian representing the Pakistan army chief was the answer. Modi and Nawaz would do the optics while the hard grind would be handled by the two NSAs.

There have been excited comparisons between the two PMs meeting preceded by the two NSAs meeting with the several Kissinger-Huang Hua meetings that had led to the famous Nixon-Mao meeting in Beijing in 1972. These comparisons are false. Nixon and Mao met after considerable details about the way forward had been worked out by Kissinger and Huang.

Both Nixon and Mao saw the Soviet Union as their enemy and they were looking for an understanding on this. This arrangement worked out admirably during the Afghan jihad, even though both Mao and Zhou en Lai were no longer alive. They had a common interest in handling a common adversary despite acute mutual differences.

Both leaders were powerful and could take decisions on their own. They knew they both would need to modify or move away from long-held positions and strategy. In any case, a road map had been worked out on contentious issues like dealing with the future of Taiwan.

This is not so between India and Pakistan. We do not have a common strategic interest, we have no mutual trade or economic interest, we have opposing views on regional issues, notably Afghanistan.

There is no evidence that Pakistan has changed its position on the territory occupied by it illegally and which it is now palming out to China.

Pakistan has used terrorism as a strategic foreign policy weapon against India and Afghanistan. It has given no evidence that it has given up its policy of a proxy war against India.

Writing in 2005 (external link), I had said it would be folly to fall for Pakistan's charm offensive. Acquisition of Kashmir remained the goal of the jihadis, the army and the politicians. This has not changed. I had also feared that if Musharraf's charm offensive failed 'one can expect jihadi hordes to be unleashed.' Well, we did have terror in Mumbai in 2006 and 2008 after the talks floundered.

Having to carry one albatross around one's neck is a burden enough, but Pakistan has two. One is the desire to wrest Kashmir from India and related to that is to be the suzerain in Afghanistan.

Either the present Pakistan leadership knows this and may be willing to accept that neither is possible, in which case Pakistan can be helped by its friends.

Or, and this is more likely, that they know this, but cannot politically or militarily accept this. In which case no one can help them, not even their friends and Pakistan will learn the hard way.

Today, the US wants out from Afghanistan, Pakistan wants India out of Afghanistan, while China is staying on in Pakistan, raising its profile in Afghanistan. As India gets closer to the US, Russia wants to have a closer look at Pakistan.

Pakistan wants peace on its eastern border as it tries to establish suzerainty in Afghanistan. The Pakistan-backed Taliban and its associates remain active there amidst talk of ISIS gaining a foothold there.

In this churning, it is necessary for the two countries to at least have some minimal contacts to see if there can be any benefit from this.

The surprise meeting was the relatively easy part; if the nature of relationship has to alter, then the steps ahead are going to be the more difficult ones. Which kind and how much rhetoric will be abandoned? How much will these promises translate into reality? How much is the Pakistan army on board? Given this attitude, is TAPI a serious proposition?

A great deal would depend on the ability and willingness of Pakistan to destroy its terror apparatus and function, as I wrote in December 2014 (external link), like a normal State.

For this to happen, Pakistan's military leaders have to accept that the policy of proxy wars and maintenance of an expensive war like countenance against an enemy of their own creation has damaged Pakistan more than it has damaged the enemy.

The Pathankot terror attack, however, indicates 'someone' is not happy with the talks. These are the gambles both leaders are going to take.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Vikram Sood is Advisor at Observer Research Foundation. Mr. Sood is the former head of the Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW) — India’s foreign intelligence agency. ...

Read More +