-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Bradley Hiller et al., “Rethinking Development Finance in Response to 21st-Century Challenges: Islamic Climate Finance and Post-Conflict Recovery,” T20 Policy Brief, November 2023.

The Challenge

Task Force 5: Purpose and Performance: Reassessing the Global Financial Order

Global challenges are becoming increasingly complex and interconnected, from the escalating impact of climate change, to the swelling numbers of refugees, to rising food insecurity. Traditional development financing mechanisms are proving insufficient to address these challenges. Therefore, there is a need to introduce new financing models and prepare existing models to unlock resources and tackle underlying causes. New collaborations must be developed with non-traditional partners, such as the private sector, to ensure that funds flow to where they are needed most.

This policy brief explores new thinking in development finance through two examples—Islamic financing for climate action and development assistance in post-conflict and fragile contexts. The brief argues that it is possible to mobilise new development finance quickly in order to address these interconnected global challenges. However, donor countries, including the G20 countries, must explore new approaches that build upon existing global structures in new and innovative ways.

The international community is falling short of the Paris Agreement goals, with the 1.5°C global warming target likely to be exceeded within the next two decades. Urgent system-wide transformation, including an overhaul of the global financial system, is therefore required to avoid a global climate disaster.[1]

Despite annual climate finance almost doubling from 2011 to 2020, finance flows need to increase at least seven-fold (to US$4.3 trillion) by 2030 in order to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.[2] Climate finance from public and private sectors as well as from conventional and innovative sources needs to be mobilised.

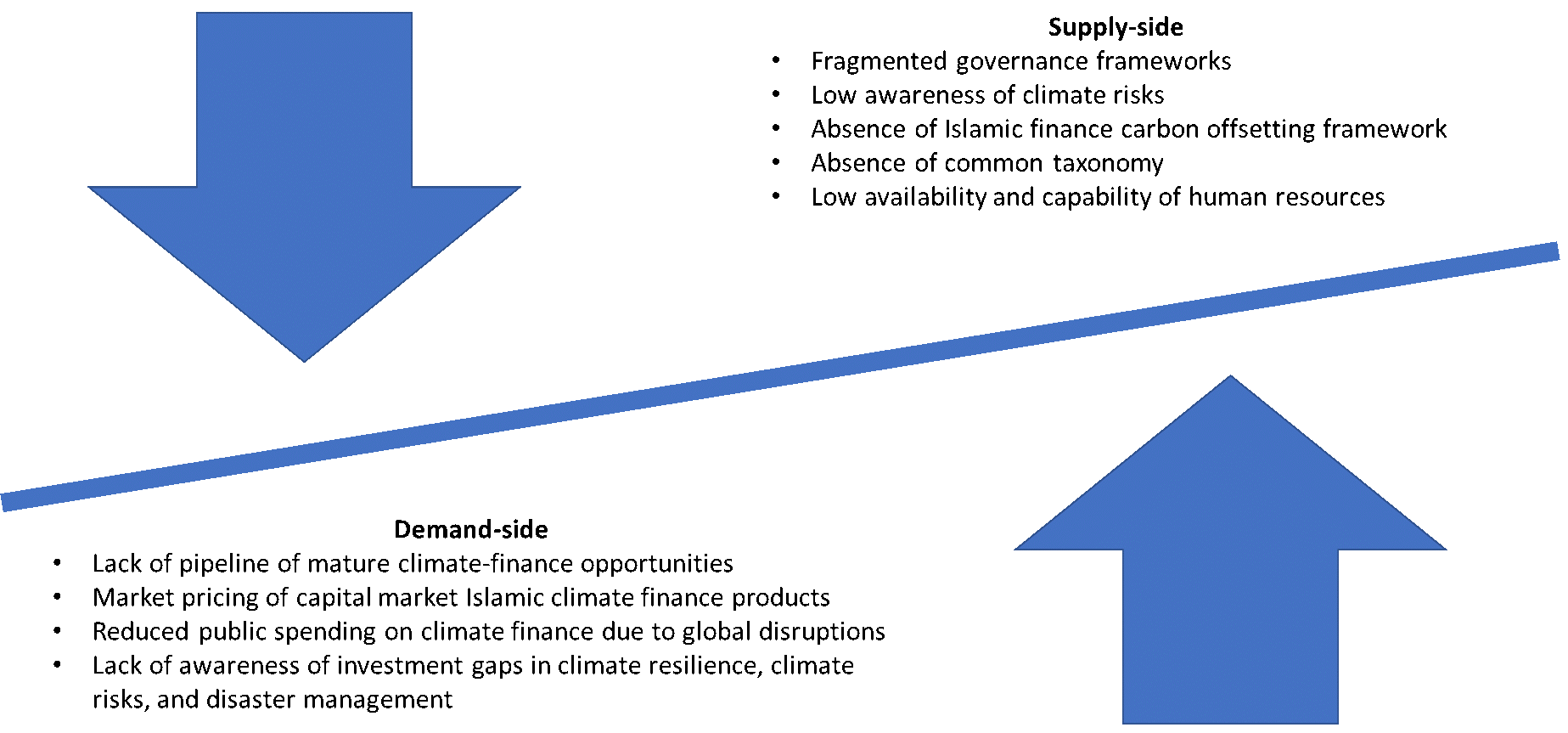

One modality that has the potential to support the global climate agenda is Islamic finance. Islamic finance emerged in the 1970s and refers to the provision of financial services in accordance with Islamic jurisprudence (Shari’ah). Today, it is an almost US$3 trillion industry[3] that is present in over 80 countries.[4] With its asset-backing and risk-sharing, Islamic finance can diversify the funding and risk exposures of conventional investors and contribute to the stabilisation of the global financial system against factors such as over-leverage and short-termism. Islamic finance principles support the protection of the environment, fair distribution of wealth, avoidance of harm, and equal opportunities for all,[5] which are well aligned with the Paris Agreement, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the 2015 Islamic Declaration on Global Climate Change.[6] However, demand- and supply-side barriers (Figure 1) have limited Islamic climate finance to less than 2 percent of the broader Islamic finance services industry.[7] Therefore, Islamic climate finance has significant potential to support enhanced global climate action.

Figure 1: Barriers to Enhanced Islamic Climate Finance

Source: Adapted from ADB and IsDB (2022)[8]

This brief draws upon the findings of a joint Asian Development Bank and Islamic Development Bank 2022 study[9] to unlock Islamic climate finance around four areas of policy support:

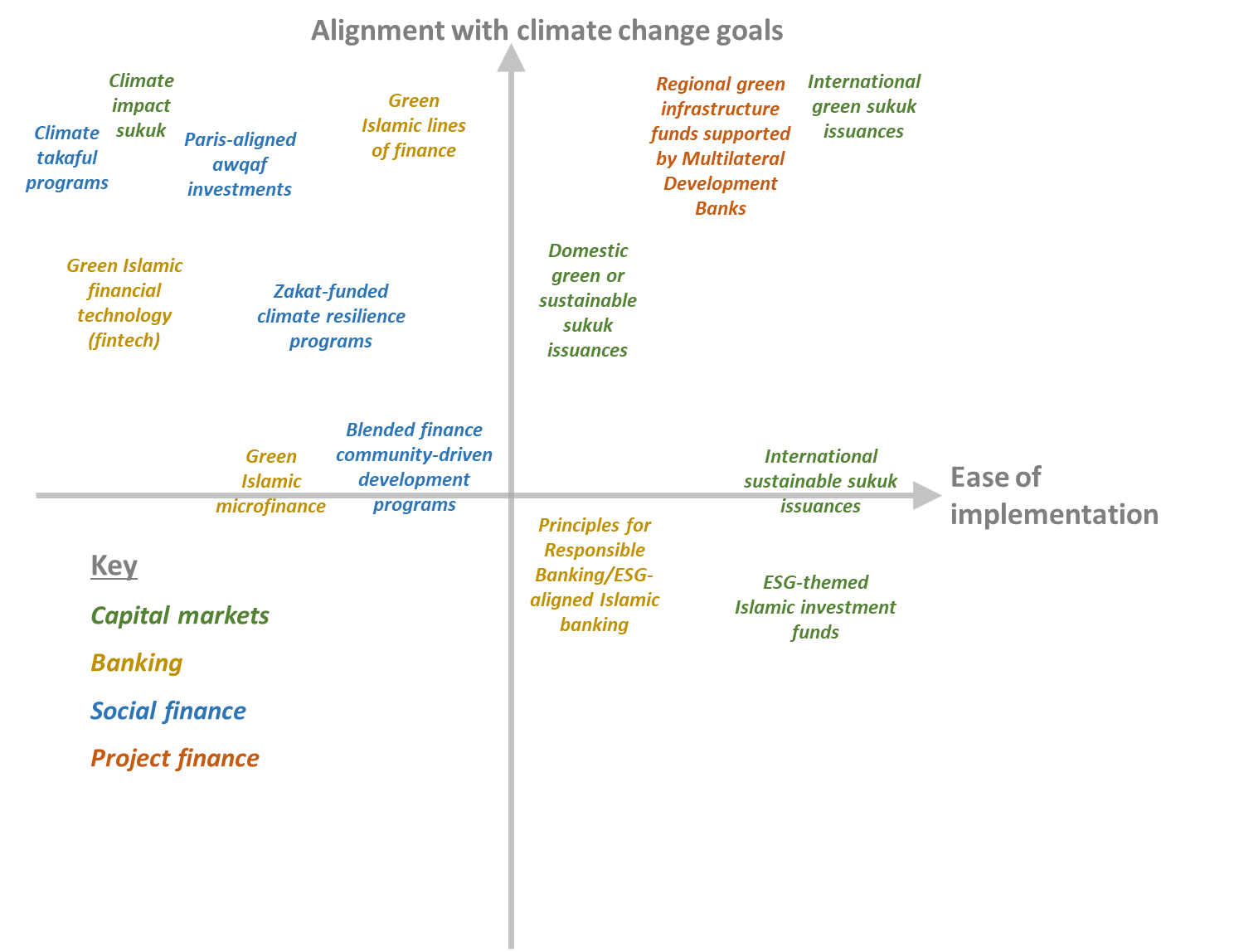

Figure 2 outlines growth opportunities for the Islamic climate finance market in the categories outlined above.

Figure 2: Islamic Climate Finance Market Growth Opportunities (Based on Alignment with Climate Goals and Ease of Implementation)

Note: Opportunities presented in the upper-right segment represent the most aligned and readily actionable.

Source: Adapted from ADB and IsDB (2022)[13]

By building upon the existing principles, structures, and networks of the broader Islamic finance industry, Islamic climate finance holds significant latent potential as an efficient and effective way to address the global climate finance shortfall. Macro-level policy support from the G20 could help activate this currently underutilised financial resource.

The past decade has witnessed a proliferation in global conflicts. As a result, the number of people displaced by conflict has more than doubled, from 42 million in 2012 to 89 million in 2021.[14] The Russia-Ukraine war, which escalated in 2022, has exacerbated these humanitarian pressures and brought conflict proliferation to Europe’s doorstep. Bilateral donors, multilateral organisations, and private-aid groups are struggling to meet the growing needs, and global appeals for support are falling far short of targets. Disruptive global trends such as climate change will likely lead to further propagation of conflict and migration.

In this context, funding for post-conflict recovery and reconstruction is receiving increased attention. Failure to support recovery efforts at the right time can undermine a country’s long-term stability and security, increase chances of conflict relapse, and prolong the plight of refugees and displaced persons.

The World Bank currently lists 35 countries and over one billion people[15] as being in fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCSs).[16] They face a variety of protracted challenges, from low institutional capacity, to limited public service delivery, to forced displacement and war.[17] Effective development assistance is critical when FCSs are attempting to transition out of conflict or fragility.

However, multilateral development organisations find it difficult to engage in post-conflict contexts, as these situations are complex, unstable, and ill-suited for the usual development financing instruments. The countries are not creditworthy. The fiscal institutions meant to oversee financial flows have atrophied and in need of rebuilding, and funding can easily end up in the “wrong” hands. Conflicts can restart, risking investments made in recovery and reconstruction. The failure of post-conflict efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq raises questions on the best ways to deploy development aid in fragile post-conflict environments.

Therefore, there is a need to focus on financing options that provide sustainable alternatives to long-term humanitarian assistance while rebuilding the capacities of local institutions and ensuring that the funds reach the right people and projects while minimising waste, misallocation, and misappropriation and navigating political pitfalls, bottlenecks, and landmines.

In 2020, the World Bank released a new strategy for engaging with fragile and conflict-affected states. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) followed with its own strategy.[18] Both strategies seek to expand available funding to fragile and conflict-affected areas. They also recognise the need for different priorities during different phases of a conflict, with more effort directed towards preventing conflicts and remaining engaged during conflicts by working to preserve and expand institutional capacity and human capital, both of which are critical for recovery efforts.[19]

The strategies are less clear about what can be done to support post-conflict recovery, which is often complex, fragile, and fraught with moral compromises. The underlying causes of the initial conflict are rarely resolved and likely to be lingering below the surface. About half of all conflicts relapse within a decade.[20] Old grievances are overlaid by new ones. Parties to human rights violations are often rehabilitated as part of political settlements, reducing the likelihood of justice and accountability. However, the strategies do emphasise the importance of rethinking what long-term success looks like, tailoring interventions to contexts, and supporting vulnerable populations.[21],[22] Four key elements include:

The G20’s Role

New and innovative thinking in development finance is required to address the complex, interconnected challenges of the 21st century. This brief calls for G20 leadership to explore and experiment with the broadening of current development financing paradigms. There is a need to introduce new institutional frameworks to mobilise additional resources and direct them more effectively towards achieving impactful development outcomes. In this regard, the G20’s role at the forefront of global development finance mobilisation can extend to support Islamic climate finance and finance for fragile post-conflict environments by building upon the following:

Recommendations to the G20

To catalyse Islamic climate finance at scale, the G20 could promote the establishment of Islamic climate finance windows in existing global climate institutions, such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF). This could elevate the profile of Islamic climate finance by leveraging existing global climate finance frameworks. This could also activate significant latent climate finance for markets and countries where climate finance is most needed. Globally recognised multilateral Islamic finance institutions could help channel public and private resources towards enhanced climate action. The establishment of a dedicated International Islamic Climate Finance Agency (and associated Global Islamic Climate Fund) could be considered subject to the success of such avenues.

Priority policy actions to mobilise Islamic climate finance under the umbrella of such initiatives include:[24]

International organisations, while trying to improve their approach,[25] are hampered by internal rules that have evolved over time to avoid risk. Even new approaches are not likely to wander far from the purview of rigorous financial oversight. In this context, the G20 can consider several innovative strategies to unlock financing in post-conflict contexts and improve the effectiveness of aid delivery:

Endnotes

[1] United Nations Environment Programme, Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window — Climate Crisis Calls for Rapid Transformation of Societies, Nairobi, UNEP, 2022.

[2] Baysa Naran et al., Global Landscape of Climate Finance: A Decade of Data, San Francisco, Climate Policy Initiative, 2022.

[3] Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), Unlocking Islamic Climate Finance, Manila, 2022.

[4] Chloe Domat, “Islamic Finance: Just For Muslim-Majority Nations?” Global Finance Magazine, November 5, 2020.

[5] Unlocking Islamic Climate Finance, 2022

[6] Bradely Hiller and Michael Rattinger, Islamic Finance and Climate Change – A Brief ADB Review, Manila, Asian Development Bank, 2019.

[7] Unlocking Islamic Climate Finance, 2022

[8] Unlocking Islamic Climate Finance, 2022

[9] Unlocking Islamic Climate Finance, 2022

[10] Zainulbahar Noor and Francine Pickup, The Role of Zakat in Supporting the Sustainable Development Goals, UNDP, 2017.

[11] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment,” June 29, 2019.

[12] Unlocking Islamic Climate Finance, 2022

[13] Unlocking Islamic Climate Finance, 2022

[14] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2021, Copenhagen, UNHCR, 2022.

[15] World Bank, “DataBank: Population, Total, Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations,” accessed April 4, 2023.

[16] World Bank, “Classification of Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations,” accessed April 4, 2023.

[17] International Monetary Fund, The IMF Strategy for Fragile and Conflict-Affected States, Washington, D.C., IMF, 2022.

[18] The IMF Strategy for Fragile and Conflict-Affected States, 2022

[19] United Nations and World Bank, Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict, Washington, D.C., World Bank, 2018.

[20] Paul Collier, “Development and Conflict,” Centre for the Study of African Economies, Department of Economics, Oxford University, October 1, 2004.

[21] Independent Evaluation Group, World Bank Engagement in Situations of Conflict: An Evaluation of FY10–20 Experience, Washington, D.C., World Bank, 2021.

[22] Independent Evaluation Group, Group Assistance to Low-Income Fragile and Conflicted-Affected States: An Independent Evaluation, Washington, D.C., World Bank, 2014.

[23] G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group, accessed June 15, 2023.

[24] Unlocking Islamic Climate Finance, 2022

[25] World Bank, Building for Peace: Reconstruction for Security, Equity, and Sustainable Peace in MENA, Washington, D.C., World Bank, 2020.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Bradley Hiller, Lead Climate Change Specialist, Islamic Development Bank; Collaborator, Centre for Sustainable Development, University of Cambridge ...

Read More +

Nader Kabbani, Senior Fellow and Director of Research, Middle East Council on Global Affairs; Research Fellow, Economic Research Forum ...

Read More +

Anders Olofsgård, Deputy Director, Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics; Associate Professor, Stockholm School of Economics ...

Read More +

Raj M. Desai, Professor of International Development, Walsh School of Foreign Service and the Department of Government, Georgetown University; Nonresident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution ...

Read More +

Daouda Ndiaye, Manager, Climate Change and Environment Division, Islamic Development Bank ...

Read More +