-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the ever-present need for a unified approach to global health governance. Despite global efforts, immunity to COVID-19 in the developing world is more a result of prior infection than it is the combined efforts of pharmaceutical companies, governments, and global health bodies, pointing to a governance vacuum. Consequently, confidence in the global solidarity rhetoric at international platforms hit an all-time low. To address this gap, at a Special Session of the World Health Assembly (WHASS) in 2021, member states agreed by consensus to establish an intergovernmental negotiating body (INB) to draft a convention, agreement, or other international instrument for pandemic preparedness and response by the World Health Organization (WHO).[1] The ‘pandemic treaty’, first proposed by Chile and the European Union (EU), has subsequently gained public endorsement by multiple world leaders and the WHO.[2] The treaty aims to improve preparedness for future pandemics and enhance global cooperation in responding to them. Negotiations to establish the treaty, led by the INB, are ongoing, building on a zero draft of the treaty presented in February 2023. These negotiations are taking place against the backdrop of stark inequalities in COVID-19 infection and mortality rates, and deepening social and economic disparities arising from the ‘syndemic’ of COVID-19 with chronic diseases and social determinants of health. There are high hopes for the treaty, and it has been termed the ‘Bretton Woods moment’ for health.[3] Still, there are some challenges that must be overcome:

A key challenge is the lack of inclusivity and diversity in global health governance. Historically, decision-making in global health has been dominated by a few powerful countries, and the voices of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and marginalised populations have been neglected.[4] This has fostered mistrust towards the global health system and compromised the effectiveness and equitability of the pandemic response. While the ‘one state, one vote’ system of the WHO is intended to deliver equity in decision-making, high-income countries have tended to wield disproportionate influence, particularly relative to smaller countries whose delegations have historically been marginalised in negotiations. Despite this, in recent years, the countries of the Global South, and particularly African countries, are becoming more effective at coordinating their efforts in order to increase their effectiveness in negotiations.[5] Whether or not the pandemic treaty ultimately reflects the interests of the populations most exposed to pandemic risks (for example, by including legally binding provisions for ensuring equitable access to medical countermeasures) will be a key measure of its success in overcoming historical shortcomings that were so evident in the global response to COVID-19. This will depend critically on the commitment of the G20.

Effective implementation of and compliance with a pandemic treaty are crucial in tackling the multifaceted challenges that pandemics present. Without robust mechanisms in place to ensure adherence, the provisions of such a treaty may not be universally upheld, compromising its overall effectiveness. This risk is underscored by past experiences with international health regulations (IHRs). The IHRs, in theory, require countries to establish and sustain certain core health system capacities. However, many LMICs have struggled to fulfill these obligations due to resource constraints and infrastructural limitations.[6] The IHRs' efficacy also hinges on the goodwill and voluntary cooperation of states in reporting outbreaks, which cannot be assumed. The COVAX facility, another significant global health initiative, provides a different yet equally instructive case. COVAX aimed to guarantee equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines worldwide, with wealthier nations pooling resources to support lower-income countries. However, from the outset, it faced significant hurdles with funding and supply. Many high-income countries prioritised vaccine acquisition for their own populations, effectively hoarding vaccines and thus undermining COVAX's principle of shared risk and benefit.[7] Both cases underscore the paramount importance of robust, adequately financed, and enforceable international health agreements underpinned by equitable distribution of resources and steadfast international cooperation.

The pandemic treaty aims to address the lack of a comprehensive and integrated approach to pandemic response. However, the legal form of the treaty is yet to be determined. If it takes the form of a framework convention, parties to the treaty may not automatically be bound by it in its entirety, which can result in a patchwork of obligations.[8] Although some governments argue that a legally binding agreement is essential to ensure that all countries take the necessary actions to prevent and respond to future pandemics, others believe that a non-binding agreement will be more effective, as it will allow for greater flexibility and collaboration among countries. Despite these differing opinions, there is a consensus that corrective action needs to be taken to address the gaps and weaknesses in the current global health system, and to ensure that the world is better prepared for future pandemics. The discussions are aimed at identifying key areas for improvement, such as better data sharing, early warning systems, and capacity building in developing countries, among others.

Whatever the treaty’s ultimate legal form, it is critical that all member states agree to its provisions and protocols, and subsequently adhere to and implement them. Given the nature of the challenges the pandemic treaty seeks to counter, any other outcome will represent a profound failure of global governance. The G20 countries must be aware of the consequences of a fragmented and siloed global health governance structure and unite in pressing for a more comprehensive instrument. The pandemic treaty must include clear and specific guidelines for implementation, as well as a system for monitoring and reporting on compliance, to ensure its effectiveness in addressing the complex and multifaceted challenges of pandemics.

Among a variety of possible framings, Regime Complex theory provides a valuable lens through which to view these challenges. It suggests that international governance challenges can be addressed by promoting coordination and cooperation among multiple international institutions and actors.[9] The theory argues that no single institution or actor can effectively address complex global challenges such as pandemics. Instead, a network of international institutions and actors can work together to create a more comprehensive and integrated approach to pandemic response. In the context of the pandemic treaty, the theory suggests that implementation and compliance issues can be addressed by creating a network of international institutions and actors that work together to oversee the implementation and compliance of the treaty. This network will include international organisations such as the WHO, as well as national governments, civil society organisations, and other stakeholders. Applying this lens to questions of implementations highlights the importance of mechanisms to foster collaboration, such as by promoting information sharing, capacity-building, and the creation of norms and standards across the network of international institutions and actors. This could involve creating mechanisms for sharing best practices and lessons learned, building capacity in low-income countries, and promoting a culture of compliance and transparency. These efforts could be significantly bolstered by the commitment of the G20, and their ability to foster such a collaborative network.

The inclusiveness and participatory nature of the treaty’s development and negotiation will be paramount to its success. The INB that has been formed to take the work forward, which includes representatives from 194 WHO member states, is a good start. It is vital that this process engages diverse stakeholders from different sectors and backgrounds, and prioritises the perspectives and needs of vulnerable populations, including women, children, refugees, and people living in poverty, who are disproportionately affected by pandemics.[10] From inequalities in mortality and morbidity rates when comparing high-income countries and LMICs, to gender-based inequality experienced as long-term social impacts of the disease, the discriminatory nature of the impacts of the pandemic should be fully acknowledged.[11] While these principals are embodied in the zero draft of the treaty, how far the finally agreed instrument goes in addressing the underlying and embedded causes of health inequities remains to be seen. Groups such as the G20 should make explicit their commitment to this principle, which will rely upon purposeful collaboration and coordination across sectors and actors, including governments, civil society organizations, and the private sector.

The social position of countries, such as their level of economic development, political power, and influence in the international community, will have a significant impact on the development and implementation of a pandemic treaty. Countries with greater political power and influence may be more likely to drive the negotiation and adoption of the treaty, while smaller or less powerful countries may have less of a voice in the process. Correspondingly, high-income countries may have a greater capacity to implement and comply with the provisions of the treaty due to their greater access to resources and infrastructure. This is concerning, given that it has become increasingly clear that LMICs have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic and have limited access to essential resources such as vaccines, medical equipment, and financial support. The pandemic also showed the might of the global scientific establishment; following the successful development of several COVID 19 vaccines, there are around 200 MRNA-based medicines for different conditions under clinical trial across the world. However, the experience of the pandemic makes it doubtful if the benefits of these scientific breakthroughs will be equitably available to populations across the world. The negotiation around the pandemic treaty provides a narrow window of opportunity to address these disparities.

A multifaceted approach is needed to understand and address the diversity and complexity of challenges in global health governance. Three theoretical frameworks—the Kingdon Model,[12] Diderichsen Model,[13] and Dahlgren-Whitehead Model[14]—provide valuable contributions to an understanding of differential vulnerability in the context of the pandemic treaty:

By making use of these established theoretical frameworks in their deliberations, those involved in the development of the pandemic treaty can ensure that they are attentive to the needs of all countries, regardless of their social or economic position, in pursuing a treaty that prioritises equity.

The treaty negotiations include an explicit aim to build on and synergise with existing frameworks for global health governance such as the IHRs, incorporating lessons learned from the failures and inadequacies, rather than replicating them.[15],[16] The successful alignment of the treaty negotiation process with the ongoing process to revise IHRs is thus paramount. In addition, the pandemic treaty should adopt a comprehensive and integrated approach to pandemic response. Alignment with WHO’s Universal Health and Preparedness Reviews (UHPRs) should ensure that the treaty goes beyond a narrow focus on medical aspects of pandemics, to take full account of the social, economic, and political factors that contribute to their spread and impact.[17] Similarly, investments made by the Pandemic Fund should be aligned to address critical gaps in capabilities needed to fully implement the treaty. The G20 should take account of this in wielding its significant influence in the processes that shape these mechanisms and how they work together.

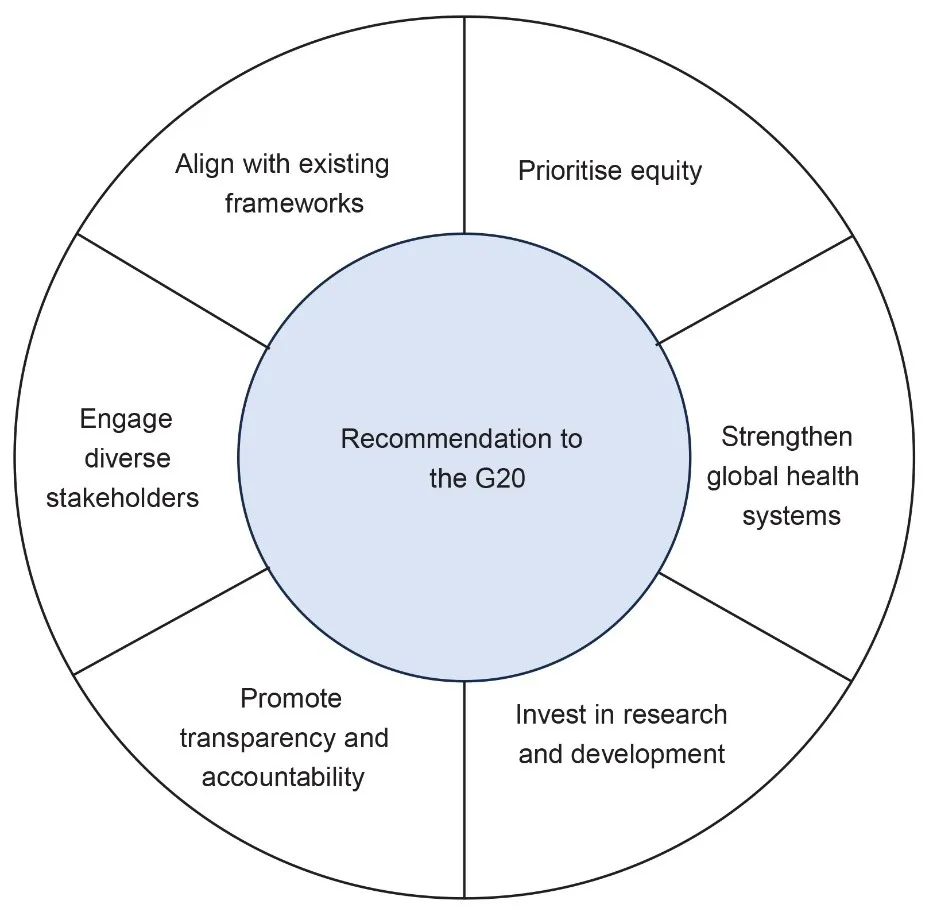

Based on the challenges and solutions outlined above, this policy brief recommends the G20 countries embrace the following principles for enhancing inclusivity, diversity, and vulnerability analysis in global health governance in their contribution to the ongoing negotiation of the pandemic treaty, individually and collectively (see Figure 1). The G20 has a key role to play in ensuring that these principles are made concrete and operationalisable in the treaty negotiations, which represent a unique window of opportunity to establish a unified approach to global health governance.

Figure 1: Recommendations to the G20

Source: Authors’ own

The G20 countries, as key players in global health governance, have an essential role to play in ensuring the success of the pandemic treaty. The effectiveness of the pandemic treaty will be determined by its ability to address past shortcomings, promote equity, and foster collaboration among nations. It is vital that all member states agree to the treaty's provisions and protocols, with the G20 taking a leading role in advocating for a more comprehensive instrument. By embracing the recommendations outlined in this brief, the G20 can contribute to a stronger and more equitable global health governance system, enhancing global preparedness for future pandemics and upholding principles of solidarity and cooperation.

[a] The authors thank Rebecca Forman and Clare Wenham from LSE for their contributions.

[1] “World Health Assembly Agrees to Launch Process to Develop Historic Global Accord on Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response,” World Health Organization, accessed May 14, 2023.

[2] “Global Leaders Unite in Urgent Call for International Pandemic Treaty,” World Health Organization, March 30, 2021.

[3] Kristalina Georgieva, “A New Bretton Woods Moment,” International Monetary Fund, October 15, 2020.

[4] Bambra Clare, Ryan Riordan, John Ford, and Fiona Matthews, “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Inequalities,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 74, (2020): 964.

[5] “Today’s Challenges Require More Effective and Inclusive Global Cooperation, Secretary-General Tells Security Council Debate on Multilateralism,” United Nations, December 14, 2022.

[6] Preben Aavitsland, Ximena Aguilera, Seif Salem Al-Abri, Vincent Amani, Carmen C Aramburu, Thouraya A Attia, Lucille H Blumberg, et al., “Functioning of the International Health Regulations during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” The Lancet 398, no. 10308 (2021): 1283–87.

[7] Victoria Pilkington, Sarai Mirjam Keestra, and Andrew Hill, “Global Covid-19 Vaccine Inequity: Failures in the First Year of Distribution and Potential Solutions for the Future,” Frontiers in Public Health 10 (2022).

[8] “Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response Accord,” World Health Organization, 24 February 2023.

[9] Laura Gómez-Mera, “International Regime Complexity,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies, August 31, 2021.

[10] “Explainer: How COVID-19 Impacts Women and Girls,” UN Women, 17 March, 2021.

[11] Bambra Clare, Ryan Riordan, John Ford, and Fiona Matthews, “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Inequalities,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 74 (2020): 964.

[12] John W. Kingdon, “Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies,” Boston :Little, Brown, 1984.

[13] Diderichsen Finn, Timothy Evans, and Margaret Whitehead, “The Social Basis of Disparities in Health,” Challenging Inequities in Health: From Ethics to Action, September.

[14] Margaret Whitehead, and Göran Dahlgren, "Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health," Stockholm: Institute for Future Studies (1991).

[15] Sridhar Venkatapuram, and Rajat Khosla, “The Pandemic Treaty – One Ring to Rule Them All,” Observer Research Foundation, 4 March 2023.

[16] Clare Wenham, Mark Eccleston-Turner, and Maike Voss, “The Futility of the Pandemic Treaty: Caught between Globalism and Statism,” International Affairs 98 (3): 837–52.

[17] “Universal Health & Preparedness Review,” World Health Organization, accessed May 14, 2023.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Miss. Viola Savy Dsouza is a PhD Scholar at Department of Health Policy Prasanna School of Public Health. She holds a Master of Science degree ...

Read More +

Dr. Sanjay M Pattanshetty is Head of theDepartment of Global Health Governance Prasanna School of Public Health Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) Manipal Karnataka ...

Read More +

George Wharton Senior Lecturer Department of Health Policy London School of Economies and Political Science (LSE)

Read More +

Prof. Dr.Helmut Brand is the founding director of Prasanna School of Public Health Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) Manipal Karnataka India. He is alsoJean ...

Read More +

Oommen C. Kurian is Senior Fellow and Head of the Health Initiative at the Inclusive Growth and SDGs Programme, Observer Research Foundation. Trained in economics and ...

Read More +