-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan and Pulkit Mohan, “PLA Joint Exercises in Tibet: Implications for India,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 238, February 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

Since President Xi Jinping’s ascendency to power in 2012, China has had a more assertive foreign policy, aiming to increase its influence in the Indo-Pacific and beyond. Speaking at a press conference in March 2018, Xi highlighted China’s shift towards “rejuvenation”[1] as a world power. Xi also attached great importance to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and under his watch, the military has undergone changes in its doctrine and force modernisation.

Indeed, Xi has partly bolstered China’s rise in the region through these military reforms, beginning in 2015. Since then, there have been major changes in the operational structure of the PLA, with the modernisation and optimisation of the military to “achieve enhanced jointness and efficiency.”[2] China’s inclination towards building an improved operational force is driven by its need to safeguard its national interests amidst the changing dynamics of power.

According to the US Department of Defense’s 2018 China Power report, China’s military has introduced reforms to the operations of the PLA with the “most comprehensive restructuring of forces in its history.”[3] The PLA’s ultimate focus is to improve its ability to conduct joint operations in an effective manner. Its most recent defence White Paper 2019 highlighted maintaining combat readiness, emphasising the need “to improve the capabilities of joint operations command to exercise reliable and efficient command over emergency responses, and to effectively accomplish urgent, tough and dangerous tasks.” According to the White Paper, the PLA, since 2012, have conducted extensive mission-oriented training including 80 joint exercises at and above brigade/division level.[4]

This White Paper is a significant departure from its predecessor, published in 2015. In 2015, China maintained that its intentions in force modernisation were defensive and in the interest of safeguarding national security and development interests. On the other hand, the 2019 White Paper emphasises the impact of competition in the military sphere with the US and how China’s growing military is being developed and modernised to face such a challenge. China, according to the document, will pursue national defence goals which include safeguarding national sovereignty, unity, territorial integrity and security as well as its maritime interests.

Although China’s primary objective is to compete with the US, the strategic consequences of a more modern PLA will be felt in India as well as in its neighbourhood. China argues that seeking hegemony or expansion in its areas of influence are not part of its strategy; yet, the reality is different. Maintaining its position in the power hierarchy in the region and beyond, remains at the core of China’s goals with regard to both military modernisation and its foreign policy strategy. This has been evident in the last several years in its various policy statements. At the 6th Xiangshan forum in October 2015, for instance, vice-minister for foreign affairs Liu Zhenmin detailed some of what he called the “injustice” to China in its relations with other countries. While this is nothing new, the problem comes from the deep contradictions between China’s rhetoric and the reality. For instance, Liu called on the big powers to not seek spheres of influence, and of the small and medium countries to not take sides between big powers. The flaw in this formulation is that China looks at the world through a divided prism that categorises countries into big, medium and small, highlighting China’s hierarchical approach in international politics and the differentiated response that Beijing assumes these countries to play. Clearly, India needs to be mindful of such Chinese inclinations and work with like-minded partners in shaping an inclusive agenda in the Asian strategic space.[5]

This paper examines a particular aspect of the PLA reforms as they pertain to training and jointness in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) and the Sino-Indian border areas. No previous work has comprehensively listed or examined China’s military exercises in the Tibet region. The paper starts with an examination of the Chinese military reforms as they apply to these areas, in terms of the military restructuring and the new commands responsible for them. The paper then narrates the increasing number of military exercises being undertaken by China in these areas. The paper also examines the Sino-Indian border landscape and weighs China’s state-of-the-art infrastructure against India’s own. The paper concludes with the strategic consequences and tactical implications of these for India.

Background: PLA Military Reforms and Reorganisation

President Xi Jinping has overseen the PLA’s most comprehensive and thorough reforms in recent decades. Prior to this, the last major restructuring of the PLA was undertaken under Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s and the 1980s. A major difference under Xi’s leadership is PLA’s overall ambitious agenda to stay competitive with the global powers. A 2018 study by the American think tank RAND, noted that the military restructuring and modernisation are being undertaken primarily to ensure the absolute loyalty of the PLA to the Community Party of China (CPC), and to Xi personally as the CPC’s supreme leader. The study observed that a successful completion of the restructuring could address many of the problems that have ailed the PLA, such as its lacunae in command and control, as well as in operations.[6] This fits within the “Chinese Dream” concept articulated by Xi in November 2012, which essentially calls for a strong and prosperous country, the rejuvenation of the nation, and the well-being of its people by 2049, the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Xi had said, “The renaissance of the Chinese nation is the greatest dream for the Chinese nation in modern history.”[7]

China’s extensive military modernisation and reforms in and around the Sino-Indian border areas as well as in the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) are of particular concern to India. China’s strengthened physical border infrastructure along with the military hardware and forces in this region enhances its overall capabilities in the event of a war with India. For more than a decade now, it has been known that the Chinese PLA have erected several military camps close to the border areas, which means that their forces have grown relatively acclimatised to the region’s prevalent high-altitude conditions. On the Indian side, meanwhile, the armed forces that are responsible for the border are located in the plains of Assam, except for a few of the divisions which are close to the border. These forces are at sea level and are therefore not getting acclimatised when they should be, given that the border stands at anywhere from 9,000 feet above sea level (asl) and above. Some of these places along the border that require acclimatisation include North Sikkim and East Sikkim, Doklam, Chushul, Chumur, Demchok, Daulat Beg Oldi, Mana and Niti passes on Uttarakhand borders with China as well as most posts on the Arunachal Pradesh border with China. Under such a scenario, if the Indian military is to respond to a crisis on the border areas, they would have to clear several stages of acclimatisation before they can be deployed.

While the physical infrastructure remains a key challenge for India as it prepares its defence along the Sino-Indian border areas, a more worrying aspect has been the increasing number of Chinese military exercises, both service-specific and joint ones, in TAR. The 2017 Doklam standoff between India and China should be taken as an important reminder of the scenarios that India might need to face from a more aggressive China in the coming years.[8] The surge in PLA military exercises can no longer be ignored by India. Chinese state-run press and military media have been increasingly sharing reports of the exercises in the Tibetan plateau, possibly as a signal to India in a display of its supremacy in the military domain.[9]

While the Wuhan spirit has thawed tensions between India and China to an extent, New Delhi needs to be mindful of the increasing Chinese military deployments and capabilities in the border region.[10] For more than a decade, China has been reorganising its missile facilities, for instance, those in Delingha. Analysts using satellite imagery had pointed out more than a decade earlier that the launch sites for the older Dong Feng-4 (DF-4) ICBMs were upgraded to accommodate medium-range ballistic missiles such as DF-21.[11],[12] The PLA is reported to have two versions of it – the DF-21 with 1750 km range and DF-21A with 2150 km range, including some that carry conventional warheads.[13] Reports have also indicated the possibility that there could be longer-range missiles deployed here such as the DF-31 or the even more advanced DF-31A, which has a range of about 12,000 km.[14] All of these have been part of China’s efforts to transition from the older, liquid-fuel missiles to longer-range, road-mobile, solid-fuel missiles that are quicker to launch.[15] India’s concerns about these missiles are understandable because those positioned in Delingha can target almost all of the urban centres in northern India, including New Delhi. Any move closer to the border increases their coverage of India.

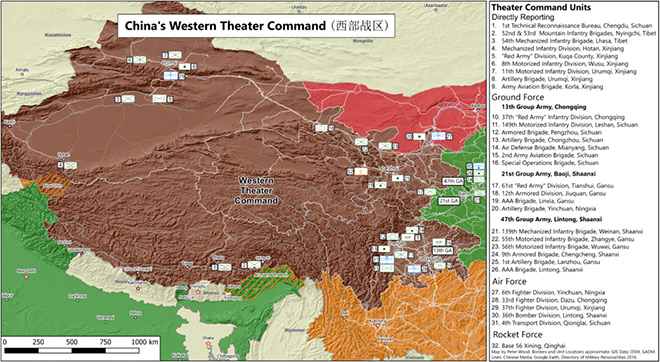

China’s major military reorganisation, announced in November 2015 at a plenary session of the Central Military Commission (CMC), too has various implications for India.[16] Senior PLA officers had suggested possible plans to reduce the number of military regions (MR) from seven to five Theatre Commands, in order to produce a more joint command with ground, naval, air and rocket forces: the Western Command, the Northern Command, the Eastern Command, the Southern Command and the Central Command, all reporting directly to the CMC.[17] (See Map 1) This plan would entail moving away from a primary focus on ground forces to mobile and coordinated movement of all services.[18]

Map 1. PLA Theater Commands

The old MR structure was seen as a hurdle in bringing about true jointness among the different wings of the Chinese military. This was seen as inefficient since the MRs had both administrative and operational obligations, and the commanders enjoyed reasonable independence, making it difficult for true integration and jointness to materialise.[19],[20]

In addition to facilitating the integration of military units, the reforms were also meant to consolidate the role of the CMC in China’s military matters. Xi had mentioned in 2015 that the CMC will have a “central and unified leadership” and will also “directly administer and command all military departments (including the PLA as well as the Chinese People’s Armed Police and China’s militia and reserve forces).”[21] Xi’s statement that these reforms were meant to ensure that “Communist Party of China has absolute leadership of the armed forces” is also noteworthy.[22] Indeed, this remains the guiding principle and philosophy of China under Xi.

One of the most striking features of the reorganisation is the creation of a new Western zone comprising more than half the country, and a Northern zone focusing on Mongolia, Russian Far East and the Korean peninsula. The new Western zone, with focus on Xinjiang and Tibet, will be important from an Indian perspective. The 2015 reorganisation brings together Chengdu (which had responsibility for most of the Sino-Indian border) and Lanzhou (which oversaw Aksai-Chin) into the Western Theatre Command. (See Map 2) This reorganisation, with enormous military resources at its command, will have important consequences in case of a border conflict between India and China.

Map 2. China’s Western Theater Command

It is noteworthy that all the military commands have been integrated with the National Defence Mobilisation Department of the CMC whereas the Tibet Military District has been put under the responsibility of the PLA.[23],[24] The establishment of the PLA Strategic Support Force (PLASSF) to conduct electronic, cyber warfare and psychological operations, and the Joint Logistics Support Force are two other significant additions that will help in improving jointness on the one hand, and strengthening the combat proficiencies on the other, by giving information support to military operations and engaging in information operations against hostile forces.[25] Many China-watchers suggest that the formation of the PLASSF reflects the importance attached to information warfare and information superiority as well as the dominance of cyber space and outer space in China’s military strategy.[26] At the leadership level, the establishment of the PLASSF has brought about an integration of the PLA strategic support forces across the services and the CMC organs. The PLASSF’s potency comes from the fact that it involves the “supporting forces for battlefield environment, information, communications, information security, and new technology testing”.[27] Additionally, China has also invested in an Advanced Info-Optical Network (CAINONET) project that seeks to link up TAR with the mainland through a widespread optical fibre cable network. Reports have noted that China also has Very Small Aperture Terminal (VSAT) satellite stations, which feed into an effective command and control network in Tibet. Furthermore, it has established comprehensive broadband connections and secure communication channels in the region.[28]

China’s growing number of military exercises in Tibet increases the threat that India faces. Xi’s emphasis on battlefield readiness and gaining more operational experience, especially in high-altitude areas, raises the possibility of even inadvertent conflicts. A cursory look at the career advancements of PLA officers who have served in the TAR shows that China is placing greater emphasis on the India-China dynamics, in general, and Tibet in particular.[29] China analyst Jayadev Ranade lists the different border defence regiments deployed by China under the Tibet Military District, near the Sino-Indian border areas. These include:

Map 3: Chinese Provinces Closer to the Border

With PLA’s growing focus on Tibet, there has been an attempt over the past decade at creating jointness amongst the different branches of the PLA. The number of exercises and overall military activities in the Lanzhou and Chengdu military regions have been noteworthy. In one of the early instances, in October 2011, the PLA was reported to have carried out two joint exercises in the Chengdu and Lanzhou military regions. These exercises were reported to be at the group army level aimed at practicing a division-size force in a truly integrated manner, involving armour, artillery and the PLAAF’s units of the TAR. It is further reported that network-centric operations in a high-intensity electromagnetic environment were also practiced.[31] Since 2013, the operational tempo of PLAAF aircrafts and helicopters also appear to have increased. In 2013, helicopters were sighted being engaged in regular patrolling of the border areas across the Ladakh sector. Reports note that in December 2013, there were new recruits who were flying for the first time in chartered civilian aircraft from Kashgar to areas opposite the Ladakh sector, and officials have reportedly said that troops travelling to this region from then on would only use air and not the roads.[32] Since August 2014, PLAAF aircraft of the Lanzhou Military Region were seen to be increasingly engaged in combat confrontation exercises, including in low-meteorological conditions.

From April 2015, J-11 and Su-27 aircraft of the PLAAF from the Lanzhou Military Region have been increasingly sighted engaging in regular exercises. That year saw the beginning of the PLAAF’s increased presence and exercises in the TAR. A regiment of the J-11 of PLAAF was also reported to be engaged in night-combat training in Tibet in early August 2015. Chinese official media had reportedly gone on to publicise J-11 heavy fighters taking off from Lhasa Gonggar’s airfield at twilight, in order to engage in a “confrontation drill.”[33]

It is reported that the PLA has begun to emphasise “the training of air battle at night” which is now part of PLA’s routine training programme.[34] China’s Z-18 (White Heron) military transport aircraft is also an important addition as far as flying in the high-altitude Tibetan plateau is concerned. There have also been regular training and live-fire exercises conducted by the regiments of the 2nd Artillery, Rocket Artillery and Army Brigade in the TAR. From mid-2015, the PLA is known to have simulated more realistic, war-like situations and environments in order to understand the problems associated with mechanical failures and battle damage repair, but more importantly to strengthen the PLA’s ability in battle command and practice the use of equipment in war-like conditions. China’s official news agency reported in August 2015 that the PLA Chengdu Military Area Command started a joint military drill, “joint action- 2015 D” that demonstrated live-fire drills.[35] The report added that this was the first of the five drills involving more than 140,000 soldiers from over 140 PLA regiments. With a growing emphasis on joint operations, the PLA had planned more than 100 joint integrated operations, all geared towards preparedness for rapid deployment along the border areas. During the second half of 2016, China’s J-20 heavy stealth fighter was seen participating in military exercises in Tibet.[36] Neither the Chinese state media nor military press have reported further details on these exercises.

As India and China were dealing with the Doklam crisis in mid-2017, the PLA was involved in a joint military exercise on the Tibetan plateau. The exercise was reported to have involved a live-fire drill with a ground combat brigade of the PLA Tibet Regional Command and was meant to demonstrate the agility of the local PLA forces and validate their combat capabilities such as assault on enemy positions and destruction of targets like bunkers.[37] A PLA press release added that “the exercise effectively tested brigade’s joint strike capabilities on plateaus”[38]. A China Daily report stated that the brigade was able to mobilise the forces along with the equipment, taking six hours to transport them from the barracks to the drill zone at an altitude of 16,400 feet asl. According to another PLA news release, the July 2017 exercise included practice sessions on rapid deployment, multi-unit joint strike and anti-aircraft defence, a reflection of the growing comfort in jointness and integration of functions.[39] Commenting on the exercise, military analyst Zhou Chenming said that while India may have more troops present in disputed areas, “China has a clear advantage in terms of speed of movement, fire power and logistics.”[40]

According to another PLA Daily article, there was a second exercise involving a live-fire war game conducted by a combat brigade of the Tibet Regional Command. The venue of the exercise was not disclosed. The reports talk about the overall upgrade of the PLA forces in Tibet. The combat brigade reportedly has acquired new types of weapons including Type-96 main battle tanks, earlier in the year.[41] A Chinese military analyst commented that these exercises suggest that the PLA has developed strong combat capability for warfare in the Tibetan plateau. He added that China has also developed a number of lightweight weapons including a wheeled infantry fighting vehicle and a new light tank for mountain warfare. Senior Colonel Wu Qian, a Chinese Ministry of Defence spokesperson, earlier in June 2017 confirmed that the PLA was testing a new type of tank on the plateaus in Tibet. Chinese media highlighted the fact that the light tank comes with a hydro-pneumatic suspension system which provides for better maneouvrability and survivability in mountainous areas.[42]

A detailed February 2018 report from a well-known Indian satellite imagery expert noted a sharp increase in PLAAF activity in Tibet, including the building of airports and helipads.[43] The report noted two- to four-fold traffic increase in some of the dual-use airports with fighter jets and the more regular deployment of early warning aircraft. Citing flight radar data, the report suggested an increase in air traffic in Tibet in December 2017 and January 2018. Flights that earlier touched only the periphery of Tibet can now reportedly reach up to Lhasa beginning in late 2017. The air infrastructure in Tibet has also been upgraded, including the Shigatse airbase; and the Lhasa Gonggar, Qamdo Bamda, and Nyingchi airports. New heliports were also built in 2017, including at Lhasa and Ngari. There has also been some construction reportedly taking place at the Cona Township in Tibet.

At the Lhasa Gonggar airport, satellite imagery showed the permanent deployment of two KJ-500 AEW aircraft. Separately, satellite imagery from late 2017 confirmed the presence of 20 J-11s, eight J-10s, and eight Mi17-IVs. The configuration of weapon platforms indicate that the Lhasa Gonggar airport may be more of a military facility than a civilian one. The February report also suggested the possible construction of a heavy military-grade third airstrip at Lhasa Gonggar airport. An underground facility is also being constructed possibly for storing ammunition. The Shigatse airbase reportedly operates UAVs that have been sighted in August 2017. Civilian flights out of Shigatse airport have also been suspended, indicating that it has become a full military facility. China is also constructing an additional airstrip in Shigatse, possibly for UAV operations. Satellite imagery indicates nine new aprons and eight new helipads constructed on this airbase. The Qamdo Bamda airport also reportedly went through an upgrade with the establishment of a longer runway in 2017 and another airstrip has been created on the Eastern side after the Doklam standoff. Developments at the Nyingchi airport suggest possible heavier traffic in the coming years. The airport has seen an upgrade with provision for additional aviation fuel, with the construction of two large storage tanks.[44]

According to other media reports, in February 2018, China’s J-10 and J-11 fighters were seen in Tibet as part of the PLA Army Western Theatre Command exercises. Chinese military leadership has said that with India importing new combat aircrafts, China will have to upgrade its air power in the Western Theatre Command, which is reported to have received far less attention until now. The PLA also conducted an exercise involving the PLA 78th Group Army, testing combat readiness in full battle gear, in February 2018.[45]

The PLA also reportedly conducted “civilian-military” integration mock exercises in Tibet in June 2018. A Global Times report had noted that these drills were meant to “test their logistics and armament support capabilities”. Zhang Wenlong, head of the PLA command logistics support department, spoke to the Xinhua news agency and highlighted the “military-civilian integration strategy and constantly advanced logistics support capabilities” at play in Tibet. He added that this approach has been executed to “solve the difficulties in personnel survival, delivery, material supply, rescue, emergency maintenance and road safety”. The report cited an example of how a local petroleum company in Lhasa was able to supply fuel to the PLA when they ran out. Reportedly, the city government of Lhasa was also actively involved in ensuring a steady supply of food for the PLA after a day of these drills. According to military analyst Song Zhongping, a major challenge in high-altitude warfare is ensuring “sustainable logistics and armament support”, and China today believes that the drill demonstrated that a military-civilian integration strategy is an appropriate one.[46]

An article released through a WeChat account of the PLA Ground Force in January 2019 talked about the new armament of the Tibet Military Command. The article said that the command is now armed with a new vehicle-mounted howitzer in seeking to enhance the high-altitude combat proficiency as part of the broader border security functions. The new howitzer, supposedly a PLC-181, was deployed with an artillery brigade in Tibet in 2017. According to Zhongping, the howitzer comes with a 52-caliber cannon and a range of over 50 km, able to shoot laser-guided and satellite-guided projectiles.[47] The PLA is also reported to have conducted intensive combat training in January and February 2019, wherein the 76th Group Army was seen participating with tanks and howitzers for a live fire shooting exercise in the remote Gobi dessert. Infantry troops from the 73rd Group Army were sent to unmapped terrain to conduct shooting practice using an entire range of weapons, including machine guns and anti-material sniper rifles. The exercise also saw an aviation brigade of PLAAF engaged in a 24-hour drill with J-16 fighter jets. A China Central Television report also mentioned an exercise in which two DF-26 ICBMs were launched during a rocket force exercise in January 2019.[48] Months after, in July, an artillery brigade of the PLA Tibet Military Region was sent to Northwest China’s Xinjiang for a live fire drill. The exercise was meant to test the real combat proficiencies including in areas such as electronic jamming and communication loopholes.[49]

PLA’s military mobilisation for training purposes and possible conflict in the future has been aided by the kind of physical border infrastructure it has developed in the TAR and Sino-Indian border areas.

Indian Gaps in the Sino-Indian Border Infrastructure

The Sino-Indian border is characterised by several imbalances. The most important of these are in border infrastructure and weapons platforms, where India’s inadequacies have worked in favour of China. There are only a few areas along the border where India has the advantage of being on higher ground.

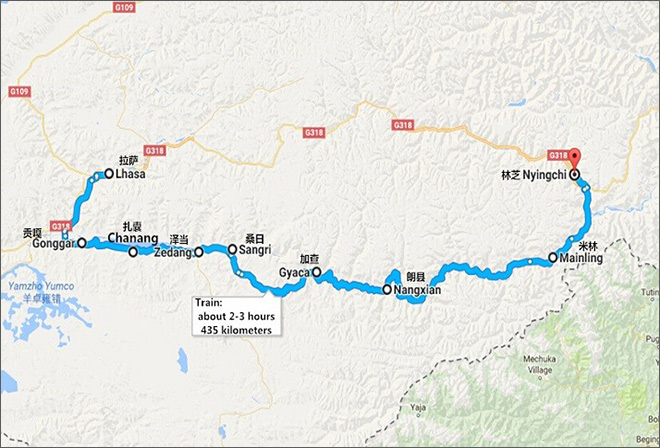

China has already developed a 96,000-km-long road network in Tibet[50] and a 2,000-km railway line from Xining, Qinghai province to Lhasa in Tibet.[51] The latter was extended to the city of Shigatse, close to the Indian border, in August 2014.[52] Further, China is developing a railway line from Lhasa to Nyingchi in the East in close proximity to the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, which is to be completed by 2021.[53]

Map 4: Distance by Train between Lhasa and Nyingchi

India should take note that the Lhasa-Nyingchi railway line will run parallel to Arunachal Pradesh. China plans to further extend this line to Sichuan and Yunan provinces as part of a broader approach to strengthen connectivity in the region.[54] Extension of these railway lines will help the PLA significantly as it would aid in mobilising troops of China’s 14th Group Army from Yunan. It could also enhance the movement of the 13th Group Army from Sichuan.

China additionally plans to launch a 1,700-km railway line from Sichuan to Tibet, connecting with areas that border Arunachal Pradesh; it is to be completed in 2026.[55] These, along with the number of helipads and airbases as well as dual-use airports will have implications for India’s border security and its ability to mobilise forces and deploy them to the border. According to reports in 2018 quoting its state-run press agency, China was set to build three new airports in the TAR, in addition to the five existing ones in the region.[56] China has also been upgrading its underground facilities at a small military town known as Lhoka, possibly to accommodate guards and troops, as well as artillery ammunition and missiles.[57] Moreover, Beijing has developed a 1,080-km-long oil pipeline from Golmud to Lhasa with a carrying capacity of 0.5 million tonnes per year.[58] The establishment of significant logistics and oil depots in the TAR suggest that China is planning for not only mobilising forces at the border quickly but also for sustaining them on the border areas for longer periods of time.

The lack of adequate border infrastructure on the Indian side has been a point of concern in the discussions on India’s military capacity and preparedness. In 2018, India’s Vice Chief of the Army Staff voiced concerns about the lack of funds for the Indian Army which is crucial in order to counter the large investments being made by China in creating and improving its strategic roads and overall border infrastructure development.[59] There has been scrutiny over how the sanctioned budget for India’s border infrastructure has always fallen short and suggestions for greater resource allocation have been repeated over time. India’s 4,056-km-long border with China has been disregarded for decades with Indian officials citing the need to protect Indian soil from Chinese incursion, similar to the 1962 border war.[60] Government officials have often argued that the poor infrastructure is not purely an incidental problem but rather it is a conscious strategy to prevent rapid Chinese ingress into Indian territory.[61]

While Prime Minister Narendra Modi, before coming into power, was critical of the previous government’s efforts at developing the border infrastructure, there has not been significant progress over the last six years, either. The infrastructure problem is exacerbated by the multiplicity of agencies that share jurisdiction over the border management.[62] The fact that the government continues to rely on the Border Roads Organisation (BRO), an organisation responsible for building strategic infrastructure in the country, is a big handicap in realising India’s connectivity projects. The infrastructure delays over the years call for a quality debate on the utility of organisations like the BRO. The acute shortage of skilled personnel has also been a continuing issue.

More recently, Prime Minister Modi seems to have stepped up the focus on border infrastructural development. India is focusing on building infrastructure on its eastern and northern borders with China, starting with the building of 73 strategic roads along its borders with China and Pakistan. Furthermore, a revised plan for five years (2018-19 to 2022-23) has been created for the construction and improvement of 272 roads (around 14,545 km) as part of the broader strategic infrastructure, according to the Minister of State for Defense.[63] The military establishment in India has been pushing for the development of all-weather connectivity in the form of roads, tunnels and underground shelters along its borders with China. Improvement in India’s border infrastructure is crucial for ensuring better mobility of troops and the logistics of storing and moving weapons, ammunition and missiles.[64]

There are strategic infrastructure projects of great significance that have faced problems which need to be addressed rapidly. The Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldi road (255 km) which runs near the LAC in eastern Ladakh has suffered from realignments and poor constructions since September 2001.[65] Tunnels are essential for storage and the covert movement of military assets. Proposed tunnels in Jammu and Kashmir, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh, for example, have suffered massive delays and are stalled in their early stages.[66] The Ministry of Defence approved 14 “strategic” railway lines in 2010, which have seen little progress. In addition to this, 73 “strategic” all-weather roads identified for construction over two decades ago, have faced massive delays.[67] The BRO has been entrusted with the construction of 61 important roads. However, only 35 of these strategic links have been completed.[68] A significant boost in India’s border infrastructure came from the inauguration of the Bogibeel Bridge in Assam, in December 2018. The 9.2-km bridge is India’s longest railroad bridge and enhances India’s defence capability by helping expedite movement of troops and military supplies to Arunachal Pradesh.[69] In 2018, Minister of State for Home Affairs Kiren Rijiju stated that infrastructural development is “taken up based on threat perception, availability of resources and various other factors like terrain, altitude etc.”[70] The director general of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), Krishna Chaudhary, acknowledged that although work has picked up pace, India has been late in ramping up its border infrastructure on the Sino-Indian border.[71]

India’s border infrastructure problems are further magnified by the multiplicity of agencies involved in securing the border. For example, the Indian Army, Indo-Tibet Border Police, Border Security Force and the Assam Rifles are all responsible for managing the border on the Indian side. This has meant that both the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) and the Ministry of Defense (MoD) have responsibility for the Sino-Indian border and the lack of coordination between different ministries and agencies has resulted in difficulties. For its part, China’s border management is managed by a single unified commander who is responsible for the TAR forces. India will therefore have to rectify its border systems and work towards a unified command structure to strengthen its defenses.

China’s border infrastructure is significantly more developed than India’s, but it is important to note that India faces tougher geological conditions in improving its infrastructure. The Himalayas is a young fold mountain range and is still rising and therefore, the construction takes place on fissured rocks mixed with clay. Also given the North-South flow of rivers on the Indian side, developing lateral connectivity is also challenging. While the terrain certainly is a problem, there are challenging tasks for China as well on specific sectors which it has managed to overcome. On the Indian side, the problem is primarily related to scaling.

For instance, the bridge-road construction ratio is tilted in favour of roads at 5 km of road against 9 m of bridge construction per day. More importantly, there is a shortage of not only qualified and skilled personnel but also heavy equipment for drilling through the mountainous terrain. Local political interference by non-qualified contractors has also been an issue. While BRO fared reasonably well in the initial decades after India’s independence, significant delays over the past many years in the completion of projects should be an imperative for a debate on the effectiveness of the BRO. Successive central administrations, including the current Modi government, have emphasised the need to expedite the development of infrastructure along the Sino-Indian border, but the delays—and the excuses for such—continue irrespective of the government in power.

Implications of PLA’s Joint Exercises

PLA’s impressive achievements with regard to troop mobilisation, joint training, and integration on the Sino-Indian border as well as in the TAR should be of concern to India. Given the unresolved border and territorial issues between India and China, the PLA’s military buildup and the overall capability mix could produce outcomes possibly in China’s favour, at least in the initial stages of a conflict. China has made significant advances for such an outcome through a number of reforms including overhauling combat units to undertake joint, integrated and “informationised” operations. China could be engaged in these for a number of reasons. One, Xi’s attempts could be to reassure the domestic audience on the combat preparedness of its military. Chinese security analysts believe that demonstrating combat readiness to adversaries can deter an actual conflict.[72]

Irrespective of the logic, PLA is attempting to address a serious lacuna with its military. Its lack of operational experience for the last several decades has been considered a serious deficiency of the PLA, and the intensive trainings and frequent joint military exercises are meant precisely to address this. PLA exercises held over the last few years have been focused on joint and integrated military operations to bring about a synergistic approach under informationised conditions. The establishment of logistics centres and oil depots in TAR and Sino-Indian border areas along with the improved road, air and rail networks have enhanced their capabilities for rapid mobilisation. This has also strengthened their capacity to sustain forces in the border areas for reasonably longer periods of time. Exercises testing their mobilisation and coordination capabilities have been undertaken through many joint exercises in the TAR.

Second, the improved physical border infrastructure that has aided the mobilisation of forces for training and joint exercises have also demonstrated the effectiveness of their command and control networks. Today, the PLA is in a position to undertake quick troop deployment to the Sino-Indian border areas. Previously, such mobilisation exercise would stretch over six months and could be undertaken only during the summer. The PLA has been engaged in military exercises to test the effectiveness of the Rapid Reaction Forces in mobilising them to the border areas in any weather or season. The quick mobilisation capabilities tested during these military exercises essentially validate the effectiveness from both operational and mobilisation perspectives.

Third, the PLA has also used these military exercises to assess the effectiveness of jointness and integration. Moving away from Military Regions to Theatre Commands is a big shift aiding the process of military integration. Nevertheless, operational jointness and integration may still be an issue. A joint and integrated planning is again not an easy task. There is no clarity on this issue until they engage in an actual operation – there have been no open reports assessing the success of the training and exercises but certainly they are making the efforts, which is worth closer examination.

Four, the overall military balance is tilted in favour of China. The former Indian Air Force Air Chief Marshal B.S. Dhanoa, for instance, had noted the big increase in the number of Chinese aircrafts in the TAR. He mentioned in particular the deployment of Sukhoi-27 and J-10 aircraft for year-round operations, giving the PLAAF possibly a major tactical boost. This is a new trend as against the earlier practice of deploying these aircrafts during summer months alone.[73] The overall mix of multi-role fighter and strike aircraft of the PLAAF can address any possible attrition during a conflict.

Five, improved border infrastructure has assisted the PLA in making a realistic appraisal of the state of their infrastructure. The multiple exercises done along the border areas and in the TAR can help identify the weaknesses and problems that need to be addressed on a realistic basis.

For its part, India’s lack of physical border infrastructure has impeded progress on multiple fronts, including its ability to undertake military mobilisation to engage in joint military exercises in the border areas. The critical role of strengthened physical infrastructure cannot be emphasised enough in this regard. India’s ability to bring about more effective jointness and integration will also depend on a better border management system, possibly under a single command structure that will focus on infrastructure and the capability mix for the border forces, and monitor the frequency of exercises.

Conclusion

Since the ascent of Xi Jinping to China’s presidency, strong emphasis has been given to the Chinese military’s competitiveness as well as that of the world’s other major militaries. This emphasis has translated to greater prominence for jointness and integration among the different arms of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), especially the PLA Army and the PLA Air Force. These joint exercises and efforts at bringing about better integration have been on full display on the Sino-Indian border areas and the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR). This brings about serious security implications for India.

The problem becomes more acute with the massive military imbalance in the border areas in favour of China, both in terms of infrastructure and equipment. India’s poor infrastructure has also impacted on the military’s ability to mobilise forces, undertake exercises to test out the vulnerabilities and gaps, and the overall jointness in terms of operations and strategic approach. The central government must undertake two important measures in this regard. One, the government has to find a way of incentivising private sector participation in infrastructure development in the border. In the harshest of terrains, private sector ventures have succeeded in setting up, for example, hydroelectric power plants. However, the private sector will not enter an area unless there is a profit calculation to its benefit. Given the strategic nature of these infrastructure projects, the central government has to find a way of encouraging the private sector to take them on.

There should be a new institutional authority established under the PMO that will track the progress of these projects on a periodic basis. While the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) has undertaken a review of these projects, these were merely recommendations that have not necessarily been followed up by the political leadership to address the inadequacies, especially the problem of multiplicity of agencies involved in the development of border infrastructure including road and rail networks and bridges. The need for a single authority for periodic monitoring and completion of these projects cannot be overemphasised. The government should constitute a parliamentary committee on strategic infrastructure which could monitor and update the status of the projects.

Given China’s apparent seriousness in its single-service and joint military operations in the Tibetan region, India should urgently step up its own capabilities on multiple fronts.

Endnotes

[1] “Xi Jinping Promises More Assertive Chinese Foreign Policy”, Financial Times, 20 March 2018.

[2] Maleeha Mukhtar, “China on Course to a Strong Military Power”, Observer Research Foundation, 11 April 2017.

[3] “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2018”, Office of the Secretary of Defense, US Department of Defense, Page 115.

[4] “China’s National Defense in the New Era”, The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, Accessed on 20 September 2019.

[5] Rajeswari Rajagopalan, “Hierarchy in the Region and China’s Strategic Culture,” Asian Politics & Policy, Volume 8, No. 2, pp. 345-46

[6] Cortez A Cooper III, “PLA Modernization: Drivers, Force Restructuring and Implications”, RAND Testimony before the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 15 February 2018.

[7] Cary Huang, “Just what is Xi Jinping’s ‘Chinese dream’ and ‘Chinese renaissance’?”, South China Morning Post, 6 February 2013.

[8] In the summer of 2017, the Indian and Chinese armies were in a standoff for 73 days at Doklam, which is a trijunction between China, India and Bhutan. While the two sides managed to avert a full-fledged conflict, the negativity developed during the conflict is unlikely to fade away. The fact that China was hosting the BRICs summit diffused the crisis in the end but the possibility of a crisis in Doklam or anywhere else in the border remains high, either due to a deliberate action by China or because of inadvertent escalation. Both India and China need to factor in inadvertent escalation as a real possibility when the two militaries are engaged in confrontations, such as the Doklam.

[9] Tom O’Connor, “China Shows Off Air Force in Direct Challenge to India Military Power in Asia”, Newsweek, 21 February 2018.

[10] Following the Doklam crisis between India and China, Indian Prime Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping engaged in a couple of “informal summits”, starting with the first one in Wuhan in China, in May 2018. The Wuhan summit was meant to reduce the tensions through a high level exchange of views in a relaxed setting without any formal agenda driving the process. This was seen as an important step given the “negativity” over the last few years between India and China. See Harsh V. Pant, “Modi and Xi in Wuhan: Bringing Normalcy Back to the India-China Relationship”, The Diplomat, 1 May 2018.

[11] Wendell Minnick, “New Chinese Missiles at Delinga?”, Defense News, 23 July 2007.

[12] “Delingha / Terlingkha – 414 Brigade”, Federation of American Scientists.

[13] Masahiro Kurita, “China-India Relationship and Nuclear Deterrence”, National Institute of Defense Studies, Japan, 2018.

[14] It has been difficult to verify if these are DF-21 or DF-31 missiles, but the TEL vehicle for both DF-21 and DF-31 look quite similar, except that the TEL vehicle for the DF-31 is around 3 metres longer. See Wendell Minnick, “New Chinese Missiles at Delinga?”, Defense News, 23 July 2007; and Fiona Cunningham and Rory Medcalf, “The Dangers of Denial: Nuclear Weapons in China-India Relations”, Lowy Institute for International Policy, October 2011.

[15] Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2019”, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 75 Issue 4, 2019.

[16] Minnie Chan, “China Hits the Launch Button for Massive PLA Shake-up to Create a Modern Liberal Force”, South China Morning Post, 25 November 2015.

[17] State Council Information Office, “China’s National Defense in the New Era.”

[18] Minnie Chan, “PLA to Announce Overhaul: Five ‘Strategic Zones’ will Replace Regional Commands, Most Army HQ to be Scrapped”, South China Morning Post, 20 December 2015.

[19] Cortez A Cooper III, “PLA Modernization: Drivers, Force Restructuring and Implications”, RAND Testimony before the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 15 February 2018.

[20] Shannon Tiezzi, “China’s Plans for a New, Improved Military”, The Diplomat, 1 December 2015.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Mu Xuequan, “Xi Underlines Reform on Military Policies, Institutions”, Xinhua, 14 November 2018.

[23] Kou Jie, “China raises Tibet Military Command’s power rank”, Global Times, 13 May 2016.

[24] Srikanth Kondapalli, “Is India ready? China Steps Up Military Build-up in Tibet as America Passes Law of Reciprocal Access”, Financial Express, 14 January 2019.

[25] China’s National Defense in the New Era, State Council Information Office; Adam Ni, “China’s Information Warfare Force Gets a New Commander”, The Diplomat, 24 May 2019.

[26] Adam Ni, “China’s Information Warfare Force Gets a New Commander”, The Diplomat, 24 May 2019; Elsa Kania, “PLA Strategic Support Force: The ‘Information Umbrella’ for China’s Military”, The Diplomat, 1 April 2017.

[27]State Council Information Office, “China’s National Defense in the New Era.”

[28] “China’s Strategic Posture in Tibet Autonomous Region and India’s Response”, National Security Alert, Vivekananda International Foundation, 2012.

[29] For an earlier account of the PLA force level in Tibet, see M Taylor Fravel, “Securing Borders: China’s Doctrine and Force Structure for Frontier Defense”, The Journal of Strategic Studies, Vol. 30 No. 4–5, 705 – 737, August–October 2007.

[30] Jayadeva Ranade, “China’s Focus on Military Activities in Tibet”, Vivekananda International Foundation, 18 September 2015.

[31] Mandip Singh “Integrated Joint Operations by the PLA: An Assessment”, Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses, 11 December 2011.

[32] Ranade, “China’s Focus on Military Activities in Tibet.”

[33] Ibid.

[34] Jayadeva Ranade, “China’s Focus on Military Activities in Tibet”, Centre for China Analysis and Strategy, New Delhi, 21 August 2015.

[35] “China’s People’s Liberation Army from Tibet Area Command Holds Major Military Drills”, Economic Times, 11 August 2015.

[36] “China’s J-20 Stealth Fighter Take Part in Military Drills in Tibet”, Defence Blog, 3 September 2016.

[37] Liu Zhen, “China Flexes its Military Muscle in Tibet, Close to Border Dispute with India”, South China Morning Post, 17 July 2017.

[38] Zhao Lei, “Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Site of PLA War Games”, China Daily, 17 July 2017.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Zhen, “China Flexes its Military Muscle in Tibet.”

[41] Lei, “Qinghai-Tibet Plateau.”

[42] Ibid.

[43] Col. Vinayak Bhat, “Tibet Sees Sharp Jump in Chinese Air Force Activity after Doklam Standoff with India”, The Print, 14 February 2018.

[44] Ibid.

[45] O’Connor, “China shows off air force.”

[46] Ananth Krishnan, “China Holds Civil-Military Drills in Tibet”, India Today, 29 June 2018.

[47] Liu Caiyu and Ji Yuqiao “Mobile Howitzers Help Tibet Border Defence”, Global Times, 7 January 2019,

[48] Chen Zhuo, “PLA undergoes intensive combat training in 2019”, China Military, 26 February 2019.

[49] “Tibet Military Region forces mobilize to Xinjiang for live-fire mock combat exercise”, Global Times, 7 July 2019.

[50] Yamei, “New roads make a more dynamic Tibet”, Xinhua Net, 2 February 2018.

[51] “Qinghai-Lhasa Heavy Rail Line”, Railway Technology, Accessed 19 September, 2019.

[52] “Now, China and Nepal to build railway line linking Tibet to Kathmandu”, Financial Express, 22 June 2018.

[53] Keith Barrow, “Construction Begins on Lhasa-Nyingchi”, International Railway Journal, 19 December 2014.

[54] Atul Aneja, “Integrating Tibet with the World”, The Hindu, 1 April 2016.

[55] Kondapali, “Is India Ready?”

[56] Tenzin Desai, “China’s New Infrastructure Projects at India’s Doorstep”, Central Tibetan Administration, 15 June 2018.

[57] Bhat, “China reinforcing underground military facilities.”

[58] “Oil Pipelines”, Tibet Facts and Figures 2005, Accessed on 20 September 2019.

[59] Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, “India Is Still Losing to China in the Border Infrastructure War”, The Diplomat, 21 September 2018.

[60] Anurag Kotoky and N. C. Bipindra, “After decades of neglect, India builds roads along China border”, The Economic Times, 12 July 2018.

[61] “India matching China in border infrastructure: Pallam Raju”, The Economic Times, 30 September 2008.

[62] Rajagopalan, “India Still Losing Border Infrastructure War.”

[63] Ibid.

[64] Rajat Pandit, “India’s military brass wants swifter build-up of border infrastructure with China”, The Times of India, 14 April 2019.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Kotoky and Bipindra, “India Builds Roads Along China Border.“

[68] Pandit, “India’s Military Brass.”

[69] “PM Modi inaugurates Bogibeel Bridge, India’s longest bridge; opens for traffic”, The Times of India, 26 December 2018.

[70] A. Arunmozhithevan and K. Gopal “Unstarred Question No: 5135- Infrastructure Development along Border”, Lok Sabha Ministry of Home Affair, Government of India, 27 March 2018.

[71] “Infrastructure along China border being enhanced at ‘galloping pace’: ITBP DG”, The Economic Times, 11 July 2018.

[72] “Chinese Army conducts live-fire drills in Tibet”, PTI, Economic Times, 12 July 2018.

[73] Shaurya Karanbir Gurung, “Significant increase in Chinese aircraft in Tibet Autonomous Region: IAF Chief B S Dhanoa”, The Economic Times, 27 April 2018.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr Rajeswari (Raji) Pillai Rajagopalan was the Director of the Centre for Security, Strategy and Technology (CSST) at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. Dr ...

Read More +

Pulkit Mohan is the Head of Forums at ORF. She is responsible for the ideation curation and execution of ORFs flagship conferences. Her research focuses include ...

Read More +