-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The survival of the Communist Party and its legitimacy depends on how seriously they understand the ground voices and act accordingly. The urgency to bring comprehensive judicial reforms may be a survival strategy.

After the tumultuous period of the ’cultural revolution’, China saw in the late 1970s a reform and opening up policy. It was in 1980 that the Organic Law of the People’s Courts (revised in 1983) and the 1982 State Constitution established four levels of courts in the general administrative structure with the SPC at the apex. In the 1990s, China had established the fundamental principle to govern the nation according to rule of law and the years 2004 and 2008 saw further steps taken in the direction without much concrete action on the ground. It was in the year 2012 that China came up with a White Paper on Judicial Reforms which recognized the need for judicial reforms in the face of growing demands for justice from the people and for China’s role in the global stage as a responsible power. It was, however, only in the Plenum of 2014 when serious discussion on rule of law and concrete steps initiated to achieve the goals laid.

The Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of Communist Party of China, which was held October 2014, was important for the right reasons. An entire plenary session was dedicated to the "Rule of law". This is for the first time that the ruling party of China dedicated an entire plenary session for such a topic. In his address to the Fourth Plenary, President Xi Jinping exhorted officials to "govern according to law", ordered Party departments to support judges and prosecutors to exercise their duties independently by "creating a favorable environment" for them to do so. He also maintained that Party committees at all levels should set an example of abiding by the law. Leaders at the Fourth Plenum also called upon ranking officials to follow the rule of law and cautioned that they would be held responsible if they interfere in the judicial activities and in the handling of cases.

The reform is part of Xi Jinping’s vision for a Chinese legal system which would be less open to influence and corruption at the local level while still being held under the final authority of the Chinese Communist Party. This peculiarity of the Chinese system where the judiciary is not independent but subservient to the Party rule needs to be kept in mind while discussing reform in China

Winds of change?

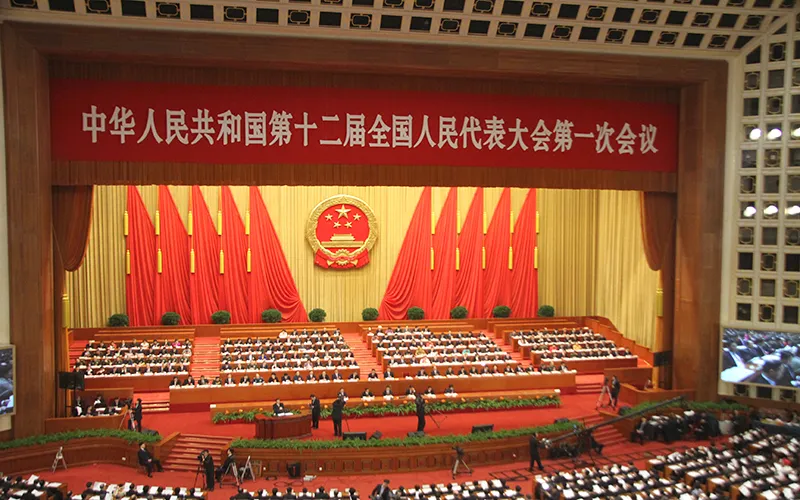

Two immediate consequences have emerged as a result of the Fourth Plenum and its emphasis on governing according to the rule of law. The first is reflected in the speech by Chief Justice Zhou Qiang, who presented the work report of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC). In his report made to the annual session of the National People’s Congress (NPC) held on March 12, 2015, he highlighted that the SPC would "make it more convenient and efficient for people to seek legal services for court decisions and resolutely prevent and correct wrongful convictions". He expressed regret for the wrongful convictions during his tenure and thus resolved to implement changes, acknowledging the mistakes made in the past to move beyond and put into action changes made during the discussion of the 4th Plenum meeting.

The second consequence is the implementation plan for judicial and social reform published by the CPC Central Committee’s General Office, and the General Office of the State Council. The plan with an aim to solve the deep-seated problems that are impairing social justice in China, has unveiled a blueprint to build a "socialist judicial system characterised by justice, high efficiency and authority". Increasing judicial independence is the first major thrust that has been identified. It has also firmly resolved to reduce influence of local governments and their hold on court system by changing the way appointments and finances are handled. According to the new plan, judicial selection committees will be established at the provincial level, removing the ability of local governments to promote judges friendly to their interests

Reforms are also moving to change the decision making system, shifting from the judiciary council making the final ruling to judges deciding on a case without seeking approval of judicial council. While the judges won’t be completely independent and would have to work with the council on "some cases", the move has been seen in positive light as an incremental step towards reform. At the SPC Monitor, Susan Finder notes that the overall goal of the reforms is "to step away from the traditional model of judges as cadres," instead creating a specialized judicial force.

Reform of the judiciary has been long overdue in China and according to an official statement made in context of the meeting, the rule of law is necessary for the path of China’s economic growth, a clean government, to attain cultural prosperity and realize the strategic objective of peaceful development. But a close look at judicial reforms shows the excruciatingly slow process it has taken to come up with a workable set of reforms.

The latest initiative of the State on judicial reforms has earned appreciation and suspicion from scholars and China watchers worldwide. Skeptics have been wary of the phrase "comprehensively advancing the rule of law" by Xi Jinping and suggest that China actually follows a "rule by law" or "rule by man" over a "rule of law" approach. In China, the Communist Party is not governed by the constitution. Rather, the constitution serves the party. Thus "rule of law" here would always mean rule of law under the leadership of the Party and is unlikely to change in this Plenum too. According to Rogier Creemers of the University of Oxford, the shift to a "rule of law" with Chinese characteristics could be a great initiative for the reforms, but questions whether it is possible to have effective rule of law under a one-party system.

Critics also point out how the Communist Party influences judicial decisions in direct and indirect ways. Party groups within the courts enforce Party discipline and the Party approves judicial appointments and personnel decisions. The Party exercises direct influence in individual cases through the Political-Legal Committees (PLCs) at each level of government. Although PLCs focus primarily on ideological matters, they can influence the outcome of cases, particularly when the case is sensitive or important. Here the local governments are also important actors as they exert external interference in judicial decision making for protecting local industries, litigants or to shield themselves from liability from administrative lawsuits. They control local judicial salaries and court finances and are also influential in making judicial appointments.

Paul D. Gewirtz, Director of the China Law Center at Yale presents a hopeful view that the plenum is serious about the reforms and would not project it merely as a tool to control Chinese society but the discussion reflects the leadership’s recognition that it needs to improve and address governance issues, widespread public grievances. The plenum also has reacted positively to increase judicial openness and transparency, improve fairness to individual litigants, and further professionalize judging.

A new survival strategy

China has been dealing with multiple complexities. While on one hand it projects itself to the world as a growing, "responsible" power, domestically, it is faced with issues ranging from economic disparity, social and political unrest and the stronghold of the Party seem to be on decline in the face of these surmounting problems. In wake of such complex issues, President Xi has come up with the slogan of ’Four Comprehensives’ as a political guide to govern China. According to an editorial in the People’s Daily, which gave the slogan a definite shape, points out that while ’building a moderately prosperous society’ remains the Party’s primary objective, social justice, rule of law and clean governance are indispensable in this pursuit.’

The survival of the Party and its legitimacy depends on how seriously they understand the ground voices and act accordingly. Thus, it seems timely for the Party to change the basis for its right to rule from one that delivers economic goods to one that promises both the fairness and predictability that are currently lacking.

(The writer is a researcher at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.