-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

India is on the path to becoming a cashless society. The Prime Minister's Jan-Dhan Yojana is one more step towards a more developed India. And possibly a big step, if successful.

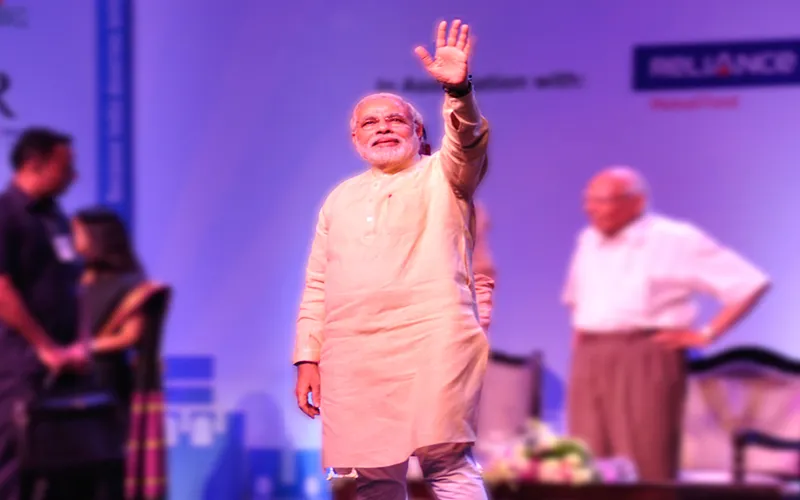

On the Independence Day, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched his financial inclusion plan to provide a bank account to every Indian household. His "Jan-Dhan Yojana", in typical Modi vernacular which plays on rhyming words, seeks to provide financial independence to unbanked Indians through a two-phase plan. Phase-I focuses on providing every household in India with a free zero-balance bank account and a RuPay debit card with an aim of increasing financial literacy amongst the poor. Account holders will also receive up to 1 Lakh Rupees of accident insurance and an overdraft of five thousand rupees (after six months). Phase-II, starting on August 15, 2015, will be focused on providing micro-insurance and pension schemes for those in the unorganised sectors.

Role of technology

Whether or not Modi's financial inclusion plan will be a success relies on probably the biggest challenge his government will face in rolling it out: outreach. Early response to the programme has been great. The government targeted one crore accounts to be opened on the first day. They exceeded their target by 50 percent as one and half crore accounts were opened from almost 80 thousand government run camps. Despite this, there are concerns about whether banking facilities can be provided to the most remote parts of India. The answer perhaps lies in mobile technology. In his Independence Day speech, the Prime Minister expressed concern that Indians have mobile phones and not bank accounts. With over 900 million mobile subscriptions in India, mobile banking is a great opportunity to reach the government's target of 100 per cent banking coverage in India. Despite there being very low smart phone penetration in India, mobile banking can facilitate widespread usage of formal banking facilities through technologies aimed at all mobile phone models, particularly feature phones that lack internet connectivity. Telephone banking and technologies such as USSD (Unstructured Supplementary Service Data), which works in a similar way to SMS, will allow people in remote parts of the country to use basic banking facilities. It is quite ironic to note that a technology less than two decades old is vital in spreading the adoption of a service that has been available for centuries.

Benefits

The importance of financial inclusion in terms of economic growth and development cannot be understated. At the microeconomic level, it provides social security for each household in India as they are no longer subject to extortion practices arising from banking in the informal sector, for example, predatory lending from loan sharks. The government will also have a direct means to provide welfare to a person in need, which in turn helps curb corruption arising from cash-in-hand delivery of welfare.

At the macro-economic level, financial inclusion has a major impact on economic growth. It will help to formalise many industries as income can be catalogued and taxed more efficiently. This in turn leads to better estimates of economic data, allowing for more transparency in the economy and more accurate forecasts. Also, increased tax revenue would increase government spending, allowing for increased financing of government led infrastructural developments. More bank accounts would lead to an increase in reserves for Indian banks. This allows for more loans to be taken out and increases consumption and investment in the economy, both major components of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). One of the Modi government's major concerns is India's stubbornly high inflation rate post the 2007/08 financial crisis. In a society with very few or no unbanked people, the Reserve Bank of India can not see greater effects of their monetary policy decisions. As there are more people with bank accounts, high interest rates will result in more people saving, therefore reducing the inflation rate.

Drawbacks

Despite the popularity of the financial inclusion scheme, it has its fair share of critics. Apart from the issue of outreach, critics argue that providing India's poor with a bank account is not enough to ensure financial inclusion. Without there being tailor made financial products to suit the needs of the poor, the plan will lead to many dormant accounts making the scheme irrelevant.

Phase II of the plan aims to tailor financial products to the poor through pension schemes and micro insurance. However, we are still a long way from being able to provide products such as short-term or low collateral loans. Another concern is that the scheme could result in an unstructured dole out of subsidies as there is currently no clear method of collecting repayments once an overdraft has been disbursed. This issue is further aggravated by the fact that the accounts are being offered to everyone, with screening being done later. As a result, people who already have bank accounts have access to the scheme, making the possibility of misuse a valid concern.

Some of the concerns mentioned above can be alleviated through stricter regulation and monitoring. Along with that, it is imperative for the government to ensure that their scheme is appropriate for the target audience it is meant for. The best way to do that would be through providing tailored financial products and services to the average owner of a bank account through the Jan-Dhan Yojana. This will ensure widespread adoption, increased inclusion of the population into India's financial system and potentially lower risk for banks. India is on the path to becoming a cashless society. The Prime Minister's Jan-Dhan Yojana is one more step towards a more developed India. And possibly a big step, if successful.

(The writers are with Observer Research Foundation, Delhi)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.