Since independence, India’s official map depicts Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) as a part of its territory currently under Pakistani occupation, terming it as Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). Unfortunately, however, India’s engagement with GB has been limited to cartographic assertions, despite real issues in the region that demand serious attention.

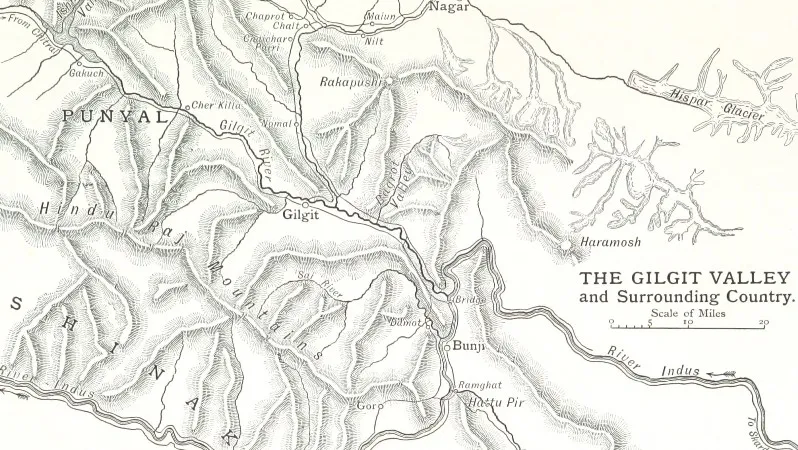

The region’s tryst with Kashmir began with Gilgit’s annexation by the Sikh army in 1843. After the Sikh empire folded, Gilgit’s control went to the newly established princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, the Maharaja was encouraged by the British to conquer more territories to the north of Kashmir, to fend off a potential Russian invasion from the northern frontier.

In the seven decades following the inception of the Kashmir dispute, New Delhi has barely raised the issue of Gilgit-Baltistan or the plight of its population, which is not even constitutionally represented. From the Indian side, the only mention the region gets is as “Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (PoK).” Even in 1994, when the Indian Parliament passed a resolution stating that PoK is an “integral part of India,” there was no specific reference made to GB.

Issues never raised by India

There is a sense of alienation in the GB region due to the ethno-religious threats facing its inhabitants. In 1973, Pakistan’s then Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto scrapped state subject rule, which essentially gave those from outside GB access to land in the region. This in part altered the demography, which was earlier primarily composed of ethnic Shinas, Burushaskis, and Baltis. Later, Zia ul Haq’s Islamisation policies threatened indigenous populations, predominantly those of the Shiite, Nurbakshi, and Ismaili faith (followers of Aga Khan). Administratively, the region still does not have the status of a province, and the GB Legislative Assembly has its autonomy stifled by another decision making body — the federally elected GB council, headed by Pakistan’s Prime Minister.

The announcement of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) has brought Gilgit-Baltistan to the forefront of geopolitical wrangling, as China seeks direct access to the Arabian Sea via Gwadar Port. The actual share of economic benefits from CPEC to the GB region are yet to be declared, and due to its alienation, the population of the region is unable to change this.

Despite these issues in the public domain, New Delhi has chosen to limit its concern for the region to occasional protests by the Ministry of External Affairs. Political activists from GB have expressed their desire to engage with India on issues of substance, not cartographic claims, and have accused New Delhi of playing “a wait-and-watch game.”

Moving beyond cartographic nationalism

In what seems to be a renewed thrust to its claim over Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, the Indian government has proposed the Geospatial Information Regulation Bill, intended to “regulate the acquisition, dissemination, publication and distribution of geospatial information of India which is likely to affect the security, sovereignty and integrity of India”. The draft bill proposes a hefty fine of upto $15 million or seven years imprisonment to any person/entity whose description of the map of India does not match the Government of India’s official version. Pakistan was the first nation to respond to the new development when its permanent representative raised the issue at the United Nations, claiming that the proposed bill was a violation of international law.

With the new bill, India’s territorial assertions are reminiscent of the past conquests of the region. India is merely reproducing the same Eurocentric tactics of cartographic assertion that imply legal control. If India has genuine concern for the territory it claims as its own, it has to first stop claiming Gilgit-Baltistan only through cartographic assertions. A new approach should entail direct engagement with the people of Gilgit-Baltistan in the manner they choose. The first step India needs to undertake is to stop associating the people of Gilgit Baltistan with Kashmir, and recognize their original identities. This can open the doors for much-needed engagement in the near future.

The author is Research Intern at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. This commentary originally appeared in South Asian Voices.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV