-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

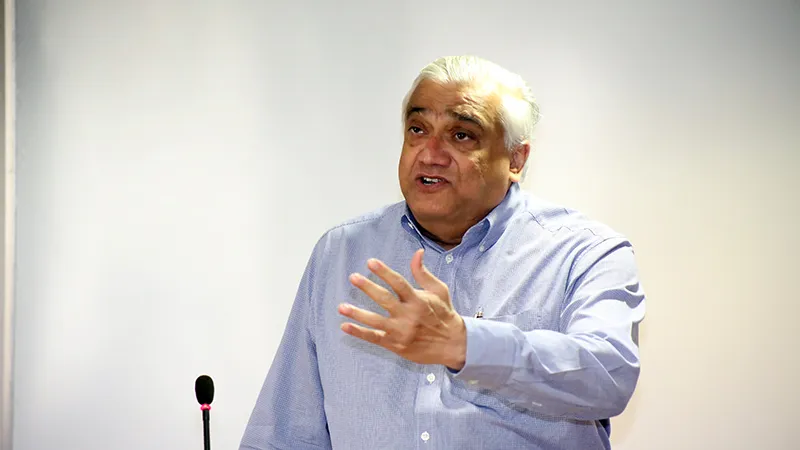

'Post-Islamism' has become the new face of political Islam which incorporates the positive and accommodating attitudes of the West towards Islam and the pluralistic attitudes of Islam towards the West, according to Mr Talmiz Ahmad, former Indian ambassador to Saudi Arabia, UAE and Oman.

"Is political Islam under threat in Egypt and Syria?" This was the theme of an interesting talk given by Mr Talmiz Ahmad, a former Ambassador to many Gulf countries, at Observer Research Foundation, Delhi, recently.

The consistent thread throughout the presentation was of transitional change and identity crisis in the West Asian region. The evolutionary stages of political movements like the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafi inspired organisations were discussed and the future of political Islam was questioned.

Mr. Ahmad, a former ambassador to Saudi Arabia, UAE and Oman, began by defining political Islam through Islamism and cited the origins of political Islam in the post Islamic revolution era and explained how Islam has played an important role in the politics of the region. He argued that Islamism as an ideology was used as a tool for political mobilisation in Afghanistan to create both local and global political groups. He also emphasised how Islamism has shaped the societal norms and conventions which further strengthen the political ethos in the region.

He traced the origins of Islamism and argued that it evolved as a response to Western domination. It was suggested that in order to understand Islamism, it is essential to develop a narrative which encompasses the importance of the Arab renaissance and its impact in shaping the responses to western imperialism. The formation of the Muslim Brotherhood was seen as a result of this anti colonial sentiment which called for the return of Islamic norms and values.

Mr Ahmad argued that the pattern which was defined by the rise and fall of the Muslim Brotherhood repeated itself throughout the 20th century and that during the late 20th century new strands of Islam which were more radical in nature were visible. He posited that scholars and practitioners alike ignored the pluralistic nature of Islam which contained strands like Islamic constitutionalism and viewed Islam as one-dimensional, by narrowly defining it in terms of Islamic fundamentalism.

The greater part of the presentation focused on the emergence of the Muslim Brotherhood and the importance of its founder Hassan al-Banna. He asserted that the leaders and thinkers who shaped the brotherhood should be viewed as individuals in order to better understand the origins of the organisation. He also suggested that during the period of Hassan al-Banna, the Brotherhood could be seen in a transitional stage which was driven by internal factions rather than external influences. It was established that the Brotherhood in the 1990s can be seen as a schizophrenic organization, as its political manifesto was riddled with contradictions. He also suggested that the problem of ’faceless’ individuals controlling the Brotherhood is prevalent in the 21st century which is exemplified by the internal divide within the brotherhood. It was contended that the reintroduction of leaders who were in complete discord with the country’s political scenario was the ’core of the problem.’

The traditionalist vs. reformist symposium can be seen as the basis of the fall of the Brotherhood as it hindered the unity within the organisation which made it impossible to take coherent decisions. It was argued that a country which was deeply polarized and had no institutions to support the national sentiment should have been led by an accommodative rather than an opportunistic government. He contended that when the constitutional debate is explored under the leadership of Morsi, it is evident that the decisions taken by Morsi were dictatorial and further polarised the society.

On the foreign policy front, he argued that there was an identity crisis which was exemplified by the Brotherhood’s relations with Saudi Arabia and Iran. The discord between what the voters wanted and what was delivered was cited as the primary reason as to why the Brotherhood failed to appease the public.

Mr Ahmad explored the distinctions between the Syrian and the Egyptian Brotherhood highlighting the pragmatic differences between the two. It was argued that both have distinct historical evolutions and therefore are very different in their attitudes towards radical Islam. He argued that, post the Hamah uprising, the Brotherhood in Syria was eliminated and this resulted in the brotherhood adopting a moderate approach which is evident in the March 2012 charter.

He argued that Syria is being used as a battleground for a proxy war between Iran and Saudi Arabia and the sectarian divide is being exploited by the two players. He contended that the sectarian tensions which have largely been created by the GCC countries will have long term effects in the region. It was argued that due to the sectarian tensions, radicals have resurfaced and both national and global groups are competing for a prominent role in the Syrian civil war. The importance of Kurds and their ever increasing demand for a separate state was also discussed in the context of the Syrian conflict. He suggested that there is a great discord among Kurdish communities and their importance is increasing in the region as the implications of any internal Kurdish conflicts will have an impact on regional politics.

After tracing the history of Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Syria and the evolution of political Islam in the region, the crucial question; ’Where do we go from here?’ was addressed. He argued that the 20th century can be seen as a period of transition which allowed Islamic movements a stage to represent themselves and participate in direct political action. This transition saw Muslim Brotherhood and Salafiya becoming strong political movements and it was suggested that it was for the first time that an "Islamic movement is now represented by a political party." Contrary to popular global liberal discourse, which argues against religious organizations, it was contended that these factions have evolved into ’significant and legitimate organisations.’

With the prospects of radicals gaining wide spread support, he suggested that radicals in the region are also following the political path and pan-regional radical organizations are emerging which do not hope to participate in democratic politics but want to advocate the role that Islam plays in a political society. Ambassador referred to the recent Egyptian polls, which showed the failure of western style secularism in Egypt to distinguish between the often perceived and the practiced secularism in the region. He argued that secularism in the region does not follow the conventional definition.

Mr Ahmad concluded by arguing that Islamism has evolved and has come to be defined by what it is not. He contended that ’post-Islamism’ is the new face of political Islam which incorporates the positive and accommodating attitudes of the West towards Islam and the pluralistic attitudes of Islam towards the West. This, he argued, is of immense importance as ’Islamism now is an integral, vibrant and immutable part of global politics and culture.’

(This report is prepared by Prabhat, Research intern, Observer Research Foundation, Delhi)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.