-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

China’s foray into the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is a major strategic and diplomatic challenge to India’s dominant role in the Indian Ocean. And promoting and securing India’s maritime interests require greater cooperation between the stakeholders in Government and the armed forces, said naval experts and former diplomats during a discussion titled “The increasing salience of India’s maritime diplomacy in the Indian Ocean Region and beyond”.

They said India has a pivotal role to play in shaping the emerging maritime security architecture and order in the Indo-Pacific. With its economic and security interests expanding rapidly and a Diaspora spread across continents, India’s maritime diplomacy -- backed by its burgeoning naval power – will be increasingly called upon to address an ever expanding range of economic opportunities, governance challenges and threats to maritime security in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) - stretching from the horn of Africa to the strait of Malacca.

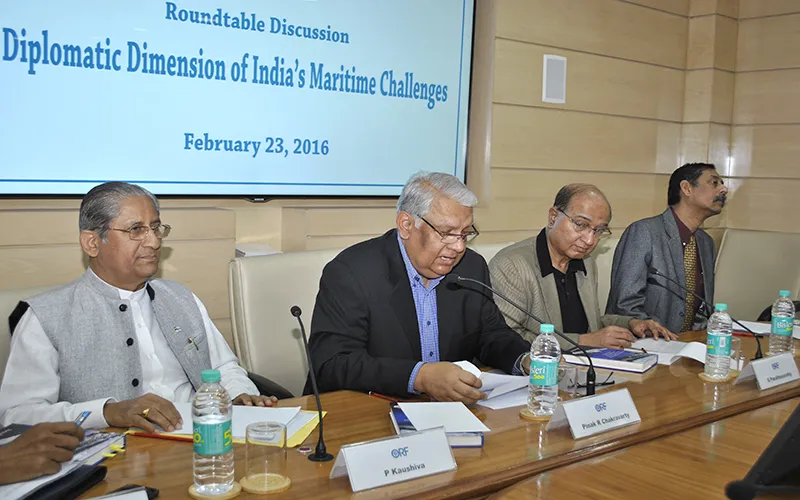

During the discussion at Observer Research Foundation on February 23, the experts stressed the need for India to build a proactive narrative to better articulate its diplomatic initiatives in the IOR and shed its ‘continental mindset’

The discussion focused on the changing character of India’s maritime calculus amidst the rapidly evolving maritime security environment in the IOR. The panel was chaired by Mr. Pinak Ranjan Chakravarty, former Secretary in the Ministry of External Affairs and Distinguished Fellow, ORF. The panellists included Mr. G. Parthasarathy, former High Commissioner to Pakistan, Vice Admiral P. Kaushiva (Retd), Mr. Yogendra Kumar, former ambassador to Philippines and Dr. P.K.Ghosh, Senior Fellow, ORF.

In his introductory remarks, Mr Chakravarty highlighted the salience of the seas to India’s overall economic well-being and prosperity. India’s ‘continental mindset’ was a product of its gradual decline as a major power in the Indian Ocean and the arrival of colonial naval powers on its soil. With growing aspirations to emerge as a great power, India should rejuvenate its long lost ‘seafaring tradition’ that was assiduously cultivated during the reign of the Kalinga, Chola and Maratha dynasties. The IOR is pivotal to the stability of global trade and commerce and serves as the torch bearer of a fast expanding ‘blue economy’. He also emphasised the geopolitical significance of the Andaman & Nicobar and Lakshadweep Islands to India’s maritime strategy in the IOR.

Mr. Yogendra Kumar’s talk was based on his recently published book, ‘Diplomatic Dimension of Maritime Challenges for India in the 21st Century’. He stated that India’s maritime capabilities developed somewhat slowly post-independence due to other security preoccupations. Despite financial constraints, India’s capacity to shape its strategic environment in the immediate neighbourhood remained intact. The end of the cold war left the detritus of failed/failing states in the IOR littoral, thus negatively impacting India’s security environment. Moreover, India’s ‘maritime blindness’ was emblematic of a loss of civilizational greatness after the onset of colonialism that turned the Indian Ocean into a ‘British Lake’.

India's maritime challenges need to be analysed in a holistic manner which encompasses the Navy, coast guard, coastal security, shipping (as an aspect of national economic and technological regeneration), and ocean affairs (climate change, ocean resources etc.). Moreover, Indian maritime diplomacy needs to look beyond traditional security rivalries in the IOR and focus its attention on the mutating ‘non-traditional’ security and governance challenges. These challenges include climate change, cyber warfare, weapons and terrorism, jihadist insurgency, piracy and armed robbery, littoral security, natural disasters and the threat from pandemics among others. He also stated that the ‘arrival’ of China in the Indian Ocean poses a strategic and diplomatic challenge to India’s role in the IOR, as the current tensions prevalent in the South China Sea (SCS) could easily spill over into the Indian Ocean.

Mr. Parthasarathy’s talk focused on the use of sea water as a source of drinking water through the appropriate use of desalination technology. He highlighted the need to harness the potential of the sea as a means to generate wave energy. While offering an overview of maritime developments around the world, he referred to China’s assertive moves in the Indian Ocean. Besides making investments in India’s immediate neighbourhood, China is also investing in potential dual-use port facilities in far flung areas of the IOR rim in places such as Djibouti in Africa. He recommended that India’s maritime cooperation should extend beyond Maldives, Seychelles and Mauritius to include Madagascar. Also, India needs a comprehensive ‘Look west’ maritime security policy that engages actively with countries in the MENA (Middle East North Africa) region. India is developing the requisite naval power to address these emerging challenges. To meet the challenges of the future, India needs to reform higher defence management as per the recommendations of the Naresh Chandra Committee report. There is also a need for greater mutual cooperation on strategic policy making among the key stakeholders within Government and the military.

Vice Admiral (Retd) Kaushiva highlighted the close cooperation that existed between the Ministry of External Affairs and the Indian Navy in the 1960s. The cooperation centred on ‘foreign cruises’ for young trainees and naval cadets to countries including Malaysia and Sri Lanka. This aspect of naval diplomacy helped improve mutual understanding between nations and their navies. In the past, many great powers including the U.K., China, several Arab countries and the United States have exploited their sea faring tradition to traverse the Indian Ocean. In the 20th century, the U.S. filled the vacuum left by the withdrawal of the British Navy to the east of Suez Canal. In the 21st century, the maritime scenario in the IOR is being shaped by the rise of China, a resurgent Japan and the U.S. pivot to the Asia-Pacific. The Indian navy has emerged as a balanced maritime force despite an uneven growth trajectory and has garnered progressively significant capabilities for power projection in the IOR and beyond.

Dr. Ghosh said a stable maritime order in the IOR is being challenged by the arrival of new powers, most notably ‘out of region’ powers like China and that the maritime security architecture of the IOR is currently in a state of flux. There is a perception that American power is waning and that other powers needed to fill this vacuum. India regards the IOR as its own ‘strategic backyard’ and is emerging as a ‘net security provider’ in the IOR, a key point highlighted in the most recent maritime strategy document of the Indian Navy. As part of this strategy, India is pursuing ‘maritime multilateralism’ through a proactive approach to maritime security by working with all of the countries in the IOR. India’s contribution includes sharing information on Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA), stationing of radars and maritime capacity building of the littoral states in the Indian Ocean among others.

While China is jostling for a presence on naval bases in places like Djibouti along with the French, Japanese and the Americans, other naval powers in the Indo-Pacific such as South Africa, Indonesia and Australia are also seeking a role in the IOR. He explained that ‘freedom of navigation’ operations and securing the ‘SLOC’ (Sea-lines of Communication) are essentially political manoeuvres by design and any attempt to interdict SLOCs in the SCS could exacerbate tensions between China and the United States. He reiterated the need for closer cooperation and coordination of diplomatic efforts between the MEA, Ministry of Defence (MOD) and the Indian Navy in promoting India’s naval diplomacy and that cooperation should move beyond ‘episodic’ Humanitarian and Disaster Relief (HDR) operations like Operation Rahat and Operation Sukoon.

During the Q&A session, participants raised concerns about the Indian Navy’s ability to garner sufficient resources to act as the ‘net security provider’ in the IOR. Discussions also focused on India’s power projection capabilities, including the appropriate size of India’s naval fleet (today India has two naval fleets stationed on its eastern and western seaboard), building and deploying the optimal number of aircraft carriers and submarines and the need for naval bases in the littoral states of the IOR. It was suggested that the Indian Navy has to constantly grapple with internal fiscal constraints as it strikes a fine balance between the quest for a quantitative leap in naval power projection and the availability of resources. Ultimately, investments in naval capability building will be a function of India’s economic performance, changes in the strategic environment and the Navy’s ‘Out of Area’ ambitions and reach beyond the IOR.

Participants also wondered as to why the U.S. was reluctant to engage with India on conducting naval exercises on India’s western sea board. From a diplomatic perspective, India would have to re-evaluate the structural processes and the mandates of regional organisations like the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) and non-governmental bodies like the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP). While the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) serves as the regional fulcrum for discussing the future security architecture of the SCS, the IOR lacks a similar regional body to address the future maritime order in the IOR.

Effective maritime diplomacy entails the need to address several emerging challenges at the same time. These include constructing instrumental regional mechanisms for economic and resource governance of the maritime commons, meeting security (traditional and non-traditional) threats at sea and enunciating effective deterrence against conventional and strategic maritime threats. The ‘use of force’ if necessary in the high seas should remain a viable and potent option in India’s diplomatic toolkit. Towards that end, the Indian Navy’s strategic mandate is to bolster India’s maritime power projection capabilities. Greater capacity building will strengthen the Indian Navy’s ability to assume increasingly complex maritime responsibilities in the wake of emerging security challenges in the Indo-Pacific. In the years ahead, maritime diplomacy is set to assume a salient role in attaining India’s strategic objective of fostering a peaceful and secure maritime order in the IOR and beyond.

This report is prepared by Ramesh Balakrishnan, Research Intern, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.