-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

This brief is part of ORF’s series, ‘Emerging Themes in Indian Foreign Policy’. Find other research in the series here:

Nivedita Kapoor, “India-Russia Relations: Beyond Energy and Defence”, ORF Issue Brief No. 327, December 2019, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

The 2019 annual summit between India and Russia in Vladivostok in early September happened alongside the fifth edition of the Eastern Economic Forum (EEF), where Prime Minister Narendra Modi was chief guest.[a] The summit laid the groundwork for enhanced economic cooperation, with various commercial documents[1] being signed by Indian and Russian entities.

Earlier in May 2018, the Sochi informal summit had led to the setting up of the Strategic Economic Dialogue between NITI Aayog of India and the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation, to identify greater synergy in trade and investment.[2] The informal summit, the first of its kind with Russia, had visible results, including the signing of significant defence deals like the S-400 missile defence system and Project 11356 class frigates. Officials also discussed various methods to improve the economic partnership, including an invitation to India to invest in the Russian Far East (RFE).

The rest of this brief will outline the most important aspects of contemporary India-Russia relations, and contextualise the partnership in the currently evolving world order.

Contemporary India-Russia Relations: Key Aspects

India is ramping up economic ties with Russia, in particular its Far East. India’s high-level engagement with the EEF began in 2017, two years after its launch. The invitation to India to invest in the RFE, extended during the 2018 annual bilateral summit, was reflected throughout 2019 in meetings held to discuss prospects for cooperation in the region.[b] During the visit of Deputy Prime Minister and Presidential Envoy to the Far Eastern Federal District Yuri Trutnev to India in June 2019, the two sides identified the areas of diamond-processing, petroleum and natural gas, coal and mining, agro-processing, and tourism for cooperation in the Far East.[3] This is in line with the trends in the region, where about 85 percent of realised FDI since 2015 has been in the primary sector[4] including oil and gas, minerals and chemicals. Indian companies currently operate in the RFE in diamond cutting, tea packaging, coal mining, and oil and gas. The commercial documents signed during the 2019 summit which relate to the RFE have been on similar lines of the natural resources sector, apart from education and investment.

Another important development was the Memorandum of Intent on the Development of Maritime Communications between the Ports of Vladivostok and Chennai. The two sides have also decided to look at “temporary placement of skilled manpower” from India in RFE.[5] Alongside a US$1-billion line of credit announced for the region, these steps indicate a desire on both sides to increase cooperation in the RFE. It remains to be seen, however, which of these MoUs and cooperation agreements will be converted to projects on the ground, as Indian companies that are new to the region are still carrying out exploratory work.

The Chennai-Vladivostok sea route, which takes 24 days to traverse versus 40 days via Europe[6] has been billed by PM Modi as the start of “a new era of cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region” which will make Vladivostok “India’s springboard in North East Asia market.”[7] The idea is being assessed for its economic profitability and viability. Meanwhile, the question of transportation of goods from Vladivostok to the European part of Russia also poses its own challenges. There is potential in the proposal of Indian manpower being engaged in a region with a population of six million and facing the problem of outmigration. Given the low level of information among Indians about the region and Russian sensitivities, it would help if the two governments facilitated the process, ensuring that the workers do not engage in permanent settlement.

For its part, Russia has also been eager to diversify its investments in the RFE, especially through the annual EEF. Its efforts in the region have had limited success owing to factors including an adverse climate, high operating cost, out-migration of population, lack of proper infrastructure, and corruption. The Western sanctions on Russia,[c] which led to a decline in western investment into the region have prompted a closer cooperation with China. This includes permission to invest in the upstream sector[8] with CNPC investing in Yamal LNG with a 20-percent stake. The $400-billion Power of Siberia deal to supply natural gas to China was another major development, locking in significant production for the Chinese market and delaying its diversification to other Asian markets. Already, Russia has become the largest supplier of oil to China, surpassing Saudi Arabia. Given the power imbalance between the two countries, Moscow has been eager to attract other countries to the region including Japan, South Korea, India and those in Southeast Asia. Moscow is hoping that as India grows to become a $5-trillion economy by 2025, it would increase its foreign investments benefitting the RFE.

The summit saw the exchange of a Joint Strategy for the Enhancement of India- Russia Trade and Investments, which has been based on discussions of the annual Strategic Economic Dialogue that began in 2018. Unlike in earlier summits, there were more commercial documents signed in this one. Apart from energy, the diamond industry and agriculture were singled out in the joint statement as areas where cooperation will be increased.

|

Table 1: Strategic Economic Dialogue – Focus Areas |

| Development of Transport Infrastructure and Technologies |

| Development of Agriculture and Agro-Processing sector |

| Small and Medium Business support |

| Digital Transformation and Frontier Technologies |

| Cooperation in Trade, Banking, Finance, and Industry |

| Tourism & Connectivity |

Source: Press Information Bureau

The target for bilateral trade figures set in 2014 Druzhba Dosti joint statement was reiterated with the goal of $30 billion by 2025. In 2018, bilateral trade rose for the second consecutive year to reach $11 billion.[9]

| Table 2: Indo-Russia bilateral trade ($ billion) | |

| 2018 | 11 |

| 2017 | 10.17 |

| 2016 | 7.71 |

| 2015 | 7.83 |

Source: Ministry of External Affairs, Indian embassy in Moscow

Private companies that are already present in the country, including SUN group, LLC KGK DV, Tata Power Co. Ltd., Murugappan group, in an encouraging sign have once again shown interest in strengthening their presence. Some of the newer private players from India include Amity University, Zee WION, Star Overseas, RUS education, H-energy, and Rooman technologies.

| Table 3: Focus of commercial agreements | |

| Private sector | Public sector |

|

Oil and gas Mining Agriculture Diamond Coal Education IT Culture |

Aircraft manufacturing Investment Mining |

Source: Press Information Bureau

In the public sector, newly formed Khanij Bidesh India Ltd has signed a cooperation agreement with the LLC Far East Mining Company. The Indian company is tasked with finding “strategic mineral assets like lithium and cobalt abroad.”[10]

The negotiations on the bilateral investment treaty, meanwhile, are yet to be completed. The talks on Green Corridor also continue. The 2018 joint statement had called for an early launch of the project, which will simplify customs operations for goods trade between the two countries. The modalities are yet to be worked out, owing to the sensitive nature of data that would need to be shared. Meanwhile, testing of the pre-arrival of data is being conducted and efforts are ongoing to ensure data security. Once again, the two countries noted the significance of the International North South Transport Corridor (INSTC) in developing bilateral trade, but its full-scale operationalisation still remains elusive.

The end of the Soviet Union led to “major structural changes in the economy and foreign trade.”[11] It led to disruption of rupee-rouble trade and banking linkages, both of which had an adverse impact on bilateral trade. The breakdown of established connectivity linkages has yet to be overcome. Russian trade has been dominated by European countries alongside Northeast Asian countries (China, Japan and South Korea) that are close to its borders. Apart from geographic proximity and strong connectivity, these are also countries with which Russia has strong banking linkages. The lack of private sector engagement has also hampered brand recognition of local companies in each other’s markets.

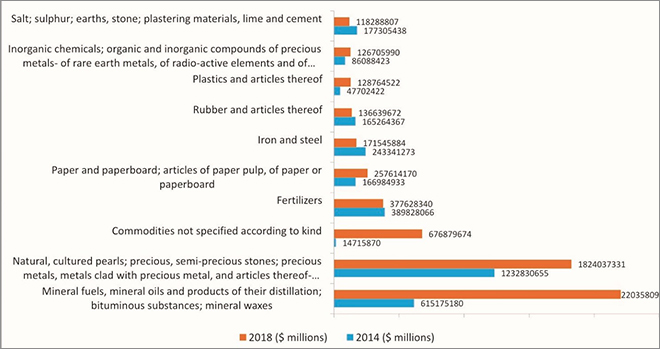

As a result of a combination of these factors, by 2015-16, India constituted only 1.2 percent of the total Russian trade while the corresponding figure for Russia stood at one percent.[12] Apart from aiming to increase trade volumes, in 2019, the two sides also agreed to “improve the structure of trade in goods and services.”[13] Indeed, there has been little change in Russia’s export profile to India over the past decade and continues to be dominated by mineral fuels and precious metals. While it is an indicator of India’s growing needs for natural resources, it also shows Russia’s limited success in diversifying its exports. The 2019 summit reiterated the importance of the oil and gas sectors, as well as mining as the centre of Indian companies’ engagement with Russia, particularly in resource-rich RFE. (See Tables 4 and 5, and Figures 1 and 2 for the bilateral trade profile.)

Figure 1: Top 10 India’s Imports from Russia in 2018 (in US$ million)

Table 4: Top 10 India’s imports from Russia (2018 vs 2008)

|

Product |

Ranking |

|

| 2018 | 2008 | |

| Mineral fuels, mineral oils and products of their distillation; bituminous substances; mineral waxes | 1 | 3 |

| Natural, cultured pearls; precious, semi-precious stones; precious metals, metals clad with precious metal, and articles thereof; imitation jewelry; coin | 2 | 4 |

| Commodities not specified according to kind | 3 | 9 |

| Fertilizers | 4 | 1 |

| Paper and paperboard; articles of paper pulp, of paper or paperboard | 5 | 7 |

| Iron and Steel | 6 | 2 |

| Rubber and articles thereof | 7 | 5 |

| Plastics and articles thereof | 8 | 27 |

| Inorganic chemicals; organic and inorganic compounds of precious metals; of rare earth metals, of radio-active elements and of isotopes | 9 | 15 |

| Salt; Sulphur; earths, stone; plastering materials, lime and cement | 10 | 13 |

Source: UN Comtrade

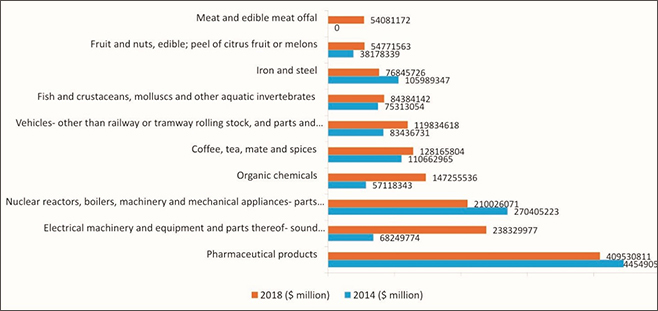

Table 5: Top 10 India’s exports to Russia (2018 vs 2008)

| Product | Ranking | |

| 2018 | 2008 | |

| Pharmaceutical products | 1 | 1 |

| Electrical machinery and equipment and parts thereof; sound recorders and reproducers; television image and sound recorders and reproducers, parts and accessories of such articles | 2 | 10 |

| Nuclear reactors, boilers, machinery and mechanical appliances; parts thereof | 3 | 7 |

| Organic chemicals | 4 | 12 |

| Coffee, tea, mate and spices | 5 | 3 |

| Vehicles; other than railway or tramway rolling stock, and parts and accessories thereof | 6 | 24 |

| Fish and crustaceans, molluscs and other aquatic invertebrates | 7 | 19 |

| Iron and steel | 8 | 6 |

| Fruit and nuts, edible; peel of citrus fruit or melons | 9 | 36 |

| Meat and edible meat offal | 10 | 90 |

Source: UN Comtrade

Figure 2: Top 10 India’s Exports to Russia

An Exim Bank study in 2015 noted that India should strive to increase its exports to Russia in sectors of machinery and instruments; electrical, electronic equipment; vehicles other than railway, tramway; pharmaceutical products, plastics and articles; articles of iron or steel; iron and steel; edible fruits and nuts; furniture.[14] In terms of Russian exports, there is promise in the areas of wood and articles of wood and other natural resources like aluminium.

Given the low volume of bilateral trade, there is also a need to push for increased private-sector engagement to achieve the 2025 targets. The expansion of ‘Make in India’ to beyond the defence sector is a welcome development. The cooperation agreement between FICCI and Roscongress Foundation as well as the MoU between FICCI and Autonomous Non-profit Organization Agency for Strategic Initiatives to promote New Projects[15] has the potential to encourage the private sector to look closely for opportunities in each other’s countries.

Indeed, the business community has been demanding a reduction in trade barriers to facilitate economic ties, which the two sides expect to address through the proposed trade agreement between the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and India. The progress on Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement also remains unclear. The effort to increase cooperation between the states and Russian regions, most prominently the RFE, has received a major push with the visit of four chief ministers. In this regard, an MoU for business collaboration between RFE and Tamil Nadu has been exchanged. With reference to cooperation in third countries, Central Asia, Southeast Asia and Africa were identified as having potential.

The energy sector was once again at the top of the priority list at the 2019 summit, where a Joint Statement on Cooperation between India and Russia in Hydrocarbon Sector for 2019-2024[16] was released. The past years have seen enhanced cooperation between the two sides, with investments in both upstream and downstream sectors with more MoUs/agreements being exchanged at Vladivostok. It has been decided to push bilateral cooperation and look for opportunities in third countries in the sector.

For India, this has been part of an effort by public-sector companies to diversify sources of imports for oil and gas. The Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, in its 2018-19 annual report has noted that Russia was added as a new source for long-term LNG imports. The first cargo of Russian LNG reached India at Dahej, Gujarat in June 2018. The overall Indian investment in Russian oil and gas assets stands at $15 billion.[17] Russia, also looking to diversify its exports, has signed an MoU on the use of Natural Gas for transportation.[d]

Russia’s investments in the downstream sector in India has been welcomed, with offer for enhancing the said cooperation in refining, petrochemical and associated sectors.[18] Rosneft, which renamed Essar Oil as Nayara Energy after a record $12.9 billion acquisition in 2017, is looking to expand its operations. The proposal is to both increase the Vadinar refinery’s capacity two-fold and expand its retail presence across India by taking its retail outlets to 7,000 in the short term.[19]

Unlike on the trade front, India and Russia met their investment target of $30 billion by 2025 ahead of schedule in 2017. Since then, this has been revised to $50 billion by 2025. For India, a large part of investment in Russia has been in the oil and gas sector. In 2016, Indian companies spent $5.4 billion in acquiring oil and gas assets in Russia.[20] In fact, Russia is the largest oil and gas investment destination for India, with a total of $15 billion investments cumulatively. Even for Russia, the Rosneft acquisition of Essar at $12.9 billion was the largest FDI in India in the sector. It was also Russia’s largest outbound deal.[21] The program for cooperation in hydrocarbons is also expected to increase the investment in the next five years.

To be sure, the results would only be visible in the coming years. In 2018, sectors of mining, metallurgy, power, railways, pharmaceuticals, IT, chemicals, infrastructure, automobile, aviation, space, shipbuilding and manufacturing of different equipment were identified in the annual summit for priority investment projects. About 40 projects under this category are either being implemented or are at an advanced stage of preparation.[22] These are in the areas of energy, space and aviation technology, the automotive industry, metallurgy, the chemical industry, pharmaceuticals and computer research. Most of the commercial documents signed in 2019 are also in these sectors.

Table 6: Overseas Projects/Assets – Indian Oil and Gas PSUs

| Sakhalin -1, Offshore |

ONGC Videsh Exxon Mobil(operator) Sodeco SMNG RN Astra |

20% 30% 30% 11.5% 8.5% |

| Imperial Energy, Russia | ONGC Videsh | 100% |

| Vankorneft |

ONGC Videsh OIL, IOCL, BPRL |

26% 23.9% |

| Taas-Yuryakh | OIL, IOCL, BPRL | 29.9% |

| License 61 |

OIL Petroneft |

50% 50% |

Source: Annual Report 2018-19, Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, Government of India.

The India-Russia Intergovernmental Commission has approved a list of 23 priority investment projects in 2018, which will focus on setting up joint ventures.[23] A cooperation agreement between Invest India and Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) has also been signed in 2019 for the purpose of investment collaboration. RDIF is also looking to collaborate with National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIIF) to carry out joint investment projects in ports and logistics.[24] Nuclear energy is another area of investment as is railways, where Russia is undertaking a feasibility study for raising the speed of the Nagpur – Secunderabad Section. In 2018, India had invited Russia to invest in industrial corridors in India, which could be another potential area of increasing investment.

A significant development since the 2019 summit was the announcement by India of a $1-billion line of credit for the RFE, the first time this instrument has been used for a particular region in a foreign country. This would assist Indian businesses in establishing themselves in a new region.[25]

Several arms deals were organised through 2018 and 2019, totalling an estimated $14.5 billion.[26] During the summit, the two governments reached an agreement on cooperation in the production of spare parts for Russia/Soviet military equipment. It was further decided to continue joint manufacturing of spare parts and others under the ‘Make in India’ programme. India and Russia have also decided to formulate a framework for cooperation on reciprocal logistics support to further their military cooperation. This comes three years after India signed the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) with the US in 2016. The agreement with the US leads to access to “designated military facilities on either side for the purpose of refuelling and replenishment” during “port calls, joint exercises, training and Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief.”[27]

Table 7: Indo-Russia Defence Deals: 2018-19

| Defence Deal | Value ($ billion) | Year |

| S-400 missile system | 5.4 | 2018 |

| Project 11356 class frigates | 0.95 | 2018 |

| Project 11356 class frigates (to be built in Goa shipyard) | 0.5 | 2018 |

| Igla-S Very Short-Range Air Defence Systems | 1.47 | 2018 |

| Akula class nuclear-powered submarine | 3 | 2019 |

| T-90 tanks | 2 | 2019 |

| R-27 extended range air-to-air missiles | 0.125 | 2019 |

| AK 403 manufacturing | 1 | 2019 |

| Total | 14.535 |

Source: Compiled from open source media reports

The defence relationship continues to be important for both partners, despite the total share of Russia in Indian market recently registering a decline. The arms exports garnered $19 billion in sales in 2018[28] for Russia and also remain an important source of maintaining close relationships with the buyers.

Table 8

| Importer – India | Main suppliers (share of total imports) | ||

| 2014-18 | Russia (58%) | Israel (15%) | US (12%) |

| 2010-14 | Russia (70%) | Israel (7%) | USA (12%) |

Source: SIPRI

With 58 percent of Indian arms imports coming from Russia in the 2014-18 period, it remains a critical partner for New Delhi. The fact that joint production and technology transfer enriches Indian producers in a relationship that is yet to be replicated with any other country underscores the importance of Moscow in Indian policy. Yet, it is only natural that India will continue to diversify as it looks for more advanced weaponry that suit the interests of its armed forces best, even if they are in a higher price range. Russia’s decision to sell its latest weaponry to China gives another impetus for India to maintain its readiness with armaments that can match that of its rapidly growing neighbour in the east.

In order to further defence cooperation, the second edition of joint Tri-Services exercises INDRA will be held in India. India was also invited to Russia’s Tsentr military exercises[29] alongside other SCO member states in 2019. Russia conducts its annual military exercises in each of its four military commands by turn. Last year, the Vostok exercises had garnered attention as Chinese troops were present for the first time. In 2019, instead of an exclusive focus on China, Russia decided to invite other states as well, even as its coordination with Beijing has grown closer, as is evident in the first-ever joint air patrols over East China Sea.

The joint statement reiterated the importance of hosting each other’s festivals, organising film fetes, and promoting their respective languages. Apart from promoting direct contacts between educational institutions, the two sides agreed that mutual recognition of academic credentials is critical. Latest figures suggest that about 11,000 Indian students are studying in Russia,[30] primarily in medical and technical courses. The number of tourists from Russia to India has been on the rise, and in 2017 it was the eighth largest source of foreign arrivals to India (278,904). In comparison, though the number of Indian tourists has registered an increase, it still remains low (71,000).

Cooperation in multilateral organisations forms a large part of the joint statement from the summit, which also highlighted coordination at the UN, BRICS, SCO, RIC and G20. India has sought to engage with major world powers in plurilateral settings while seeking to maintain a balanced policy. Russia, dealing with a breakdown of relations with the West, has focused on engaging other developing powers to stave off isolation and build on its multi-vector policy. Apart from increasing cooperation in the areas of counterterrorism, other security threats and economy, the two sides have also noted “increased role of SCO in international affairs,” looking to establish official ties of the organisation with EAEU.

The SCO, which India joined in 2017 as a full member, has also become an important venue for bilateral meetings between the two leaders. At the 2019 Bishkek summit, President Vladimir Putin and PM Modi touched base ahead of the September summit.

The initiative taken by the Russian President at the G20 summit in November 2018 to hold an informal summit-level meeting of RIC was an attempt to revive a format that has often faced criticism for failing to produce concrete results. Held after a gap of 12 years, the meeting came at a time when Russia has steadily moved away from the West. The fact that India enthusiastically participated in the same, while also engaging with JAI (Japan-US-India) at the same venue, showed India’s willingness to carry out a balanced policy – and the role it ascribes to Russia in this regard. In 2019, it was the Indian prime minister who took the lead in calling for the RIC leaders’ meeting at Osaka G20.

Adapting bilateral ties to the Changing World Order

Since the Sochi informal summit of 2018, both India and Russia have continued efforts to bolster their relationship. The 2019 summit is an important milestone to gauge the trajectory of India-Russia relations, especially given that the two have started diverging on certain aspects of navigating the changing world order.

India – Russia ties have been significantly affected by the deterioration of Russia’s relations with the West accompanied by increasing closeness between Russia and China, as well as India’s intensifying relationship with the United States. This churn in Russia’s relations has led to two different complications for Indian policymakers. First, the threat of US sanctions under its Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) for any significant Indian defence purchases from Russia, particularly the S-400 air defence system. The second is the increasing closeness between Russia and China, particularly in defence.

However, recognising that Russia is an important strategic partner and that it would be detrimental to India’s interests if the former superpower joined China in a strategic alliance, New Delhi seeks to provide Moscow with some strategic manoeuvrability vis-a-vis Beijing by maintaining strong ties with Russia. The close cooperation in defence is also a reflection of the mutual trust – engaging in joint production, transfer of technology, leasing of nuclear submarines – while maintaining strategic autonomy. Russia too, has demonstrated its willingness to bolster the relationship, as recently reflected in its support of the Indian position after the abrogation of Article 370. Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov in a telephonic conversation with Pakistani foreign minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi noted that there was no alternative but to resolve “the differences between Pakistan and India on a bilateral basis.”[31]

In April 2019, in a significant goodwill gesture, the Russians bestowed the order of St Andrew the Apostle, the highest state decoration, on PM Modi for “exceptional services in promoting a special and privileged strategic partnership between Russia and India and friendly relations between the Russian and Indian peoples.”[32] These efforts, however, have been complicated by India’s steadily improving relations with the US and its allies, especially in promoting the concept of the Indo-Pacific and the revival of the Quad, leading to divergences with Russia.

Differences have also emerged between the two strategic partners on Afghanistan. As Russia has engaged in the Moscow format of talks, it has built its contacts with the Taliban and has tweaked its Pakistan policy with an eye on Afghanistan. India has said its policy is to have an “Afghan-led and Afghan-owned reconciliation,” a stand that has been reiterated at meetings of SCO and BRICS as well as the Indo-Russia bilateral summit. However, the term has been interpreted differently by varied players.[33] India focuses heavily on “the threat from Pakistan”[34] and sees the US presence as important for stability. It has also been wary of engaging with the Taliban. In an effort to balance their positions, India and Russia have noted in the 2019 joint statement their “support for the intra-Afghan dialogue launched in Moscow” as well as other “internationally-recognized formats.”

India is suspicious of Russia’s growing closeness with China and Pakistan. Moscow and Beijing have increased their bilateral political, economic, and defence interactions—even with their power asymmetry. The July 2019 first-ever joint air patrol over East China Sea was the most recent and significant indication of this growing closeness.

In 2014, Russia decided to lift its embargo on Pakistan and agreed to supply four Mi-35 helicopters (completed in 2017) besides building a $1.7-billion gas pipeline from Karachi to Lahore. Joint military drills between Russia and Pakistan began in 2016 and have been held annually since then. In 2017, a military-technical cooperation agreement was signed which deals with arms supply and weapons development. A naval cooperation agreement was also signed in 2018.

On the Indo-Pacific, while the 2019 joint statement made no direct reference to the term, the two sides have agreed to increase consultations on development initiatives in “greater Eurasian space and in the regions of Indian and Pacific Oceans.” The joint statement attempts to find some commonality in vision between foreign policy priorities of the two countries by seeking linkages in their respective ideas. India has enunciated a much broader view of the Indo-Pacific, embracing ASEAN centrality while calling for inclusiveness and openness. India also “does not see the Indo-Pacific Region as a strategy or as a club of limited members.”[35] While Russia has expressed its reservations about the concept, preferring to use ‘Asia-Pacific’, there has been a willingness to discuss the issue.[36] As Russia looks to strengthening its pivot to the East and building on the concept of Greater Eurasia, India has the potential to engage with it on the idea of Indo-Pacific. Given that Russia also supports the central role of ASEAN[37] in the region, there is a possibility for India to attempt to bring about a change in Russia’s approach to the concept.

Conclusion

For far too long, the inability of India and Russia to vigorously diversify their ties beyond the defence and energy sectors has been noted as a serious impediment to stronger strategic ties. In the modern world, it is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain a genuinely strategic partnership without a solid economic pillar. Such economic ties could help both countries protect their relationship from being buffeted by other developments. Therefore, the focus demonstrated in 2019 on economic linkages is a welcome step forward.

It remains to be seen to what extent the groundwork laid down in 2019 will translate into action. Further steps still remain to be taken to give an impetus to trade—including conclusion of a bilateral investment treaty, Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement, Free Trade Agreement with EAEU, and the operationalisation of INSTC and the Green Corridor. There is an urgent need to enhance connectivity, most importantly, through the INSTC which is expected to “enhance trade and investment linkages.”[38] Also, its strategic value lies in enhancing India’s linkages to Central Asia, especially since the regional states have welcomed China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), making it imperative for India to up its game to expand its Eurasian presence.

There is also a need to address the legal and bureaucratic barriers in the way of effective functioning of businesses in both countries. Implementation of joint projects in defence and economy must be undertaken to facilitate the transfer of technology know-how. The Russian government needs to take steps to make RFE more attractive to foreign businesses. This would also help it to diversify its pivot to the East, which has been slow in coming and is tilted heavily in favour of China.

The institutional linkages to connect businesses on both sides have been set up and it should now be exploited by both sides to further bilateral trade. In a changing world order, both New Delhi and Moscow recognise the importance of having each other as strategic partners given their position as middle powers. This allows them to cooperate on issues of convergence at the bilateral and multilateral level. At present, India and Russia need sustained economic growth to establish themselves as important players in the world order. A failure on this front would be detrimental to their regional and global ambitions. It would be prudent for both sides to assist each other in promoting economic development while continuing to strengthen the ‘special and privileged strategic partnership’ at the bilateral level in military-technical, energy and science and technology fields.

Endnotes

[a] Apart from the joint statement titled ‘Reaching New Heights of Cooperation through Trust and Partnership,’ 49 other agreements/commercial documents were exchanged between the two sides.

[b] These included Indian ambassador to Russia meeting Minister for Development of RFE (February), a CII delegation visiting RFE (March, May), Indian ambassador meeting CEO of Russia’s Far East and Baikal region Development Fund, CEO of Far East Investment and Export Agency and First Deputy Minister for Development of Far East (April, May and July). In August, commerce and industry minister Piyush Goyal, along with the chief ministers of four Indian states—Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Haryana and Goa—visited the RFE to boost cooperation with their respective states in mining sector, the diamond-cutting industry, petrochemicals, deep wood processing, and tourism. They were accompanied by representatives of over 140 companies[b] and interacted with over 200 of their Russian counterparts.

[c] The United States (and the European Union) imposed sanctions on Russian individuals and business entities in 2014 in response to latter’s military action in eastern Ukraine and annexation of Crimea, which continue till date.

[d] The summit also saw the signing of MoU between Novatek and Petronet LNG on joint development of downstream LNG Business and LNG supplies. Zarubezhneft and Sungroup Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. also signed an MoU. The former is a Russian state oil company specializing in operationalizing fields outside Russia while the latter deals in refined petroleum products. Four Indian oil and gas PSUs have also exchanged a non-binding cooperation agreement with Rosneft, to restate their willingness to be a part of the Eastern Cluster project[d] of Russia. The current import of oil from Russia is very small[d] but it has been reported that New Delhi wants to source ‘one million barrels per day of oil and oil equivalent gas.[d]’ It is still looking for oil fields to be able to meet the target in future.

[1] Ministry of External Affairs, “List of Commercial Documents signed by various Russian and Indian entities on the sidelines of the Prime Minister’s visit to Vladivostok”, accessed October 6, 2019.

[2] Ministry of External Affairs, “Informal Summit between India and Russia (May 21, 2018)”, accessed October 10, 2019.

[3] Ministry of External Affairs, “Visit of Deputy Prime Minister of Russia to India”, accessed September 26, 2019.

[4]Paul Stronski and Nicole Ng, “Cooperation and Competition: Russia and China in Central Asia, the Russian Far East, and the Arctic”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed August 3, 2019.

[5] Ministry of External Affairs, “India – Russia Joint Statement during visit of Prime Minister to Vladivostok”, accessed September 30, 2019.

[6] Sanjaya Baru, “The Asian Mirror for the Far East: An Indian Perspective”, Valdai Discussion Club, accessed October 5, 2019.

[7] See note 7.

[8] See note 5.

[9] Kremlin, “Press statements following Russian-Indian talks”, accessed September 20, 2019.

[10] Rakhi Mazumdar, “Nalco HCL and MECL inks joint venture to form Khanij Bidesh India Ltd”, The Economic Times, accessed October 5, 2019.

[11] R G Gidadhubli, “Indo-Soviet Trade: Compulsions for Status Quo,” Economic and Political Weekly, 25: 32 (August 1990): 1765-1766.

[12] Russia Direct, “How to take Russia-India economic ties to the next level”, accessed October 25, 2019.

[13] See note 8.

[14] Exim Bank of India, “Potential for Enhancing India’s Trade with Russia: A Brief Analysis”. Working Paper no. 42, accessed November 2, 2019.

[15] Ministry of External Affairs, “List of MoUs/Agreements exchanged during visit of Prime Minister to Vladivostok”, accessed October 8, 2019.

[16] Press Information Bureau, “Joint Statement on Cooperation between India and Russia in Hydrocarbon Sector for 2019-2024″, accessed September 16, 2019.

[17] Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, “Annual Report 2018-19”, accessed October 4, 2019.

[18] The Times of India, “India pitches for stake in Far East oilfields, higher imports of oil from Russia”, accessed November 7, 2019.

[19] Rosneft, “Indian Nayara Energy’s Retail Network Expands to over 5,000 Fuel-Filling Stations“, accessed November 8, 2019.

[20] See note 17.

[21] Livemint, “Essar Oil , Rosneft say $13 billion sale completed”, accessed October 26, 2019.

[22] Invest India, “India and Russia: Enduring Partnership in a changing world”, accessed November 6, 2019.

[23] Ministry of External Affairs, “Protocol of the 23rd session of the IRIGC-TEC”, accessed October 29, 2019.

[24] The Economic Times, “Russian Sovereign Fund to invest in Indian infrastructure”, accessed October 15, 2019.

[25] See note 6.

[26] TASS, “India orders $14.5 billion worth of weapons from Russia”, accessed November 18, 2019.

[27] Dinakar Peri, “What is LEMOA”? The Hindu, accessed November 5, 2019.

[28] The Moscow Times, “Russia’s Arms Exporter Sold $19Bln Worth of Weapons in 2018, Official Says”, accessed October 6, 2019.

[29] Press Information Bureau, “Curtain Raiser – Ex Tsentr 2019”, accessed November 9, 2019.

[30] Ministry of External Affairs, “Indian Students studying in Foreign Countries”, accessed October 8, 2019.

[31] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Press release on Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s telephone conversation with Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan Shah Mahmood Qureshi”, accessed November 9, 2019.

[32] Kremlin, “Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi presented with Order of St Andrew the Apostle the First-Called”, accessed October 6, 2019.

[33] Rakesh Sood, “No good options in Afghanistan”, Observer Research Foundation, accessed November 26, 2019.

[34] Avinash Paliwal, “New Alignments, Old Battlefield: Revisiting India’s Role in Afghanistan”, accessed November 25, 2019.

[35] Ministry of External Affairs, “Prime Minister’s Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue”, accessed November 27, 2019.

[36] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s remarks at a meeting of the Dialogue of Young Diplomats from the Asia-Pacific Region”, accessed October 18, 2019.

[37] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s remarks and answers to questions during the Valdai International Discussion Club’s panel on Russia’s policy in the Middle East”, accessed November 6, 2019.

[38] Arun S, “Russia – a forgotten trade partner”? accessed November 18, 2019.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Nivedita Kapoor is a Post-doctoral Fellow at the International Laboratory on World Order Studies and the New Regionalism Faculty of World Economy and International Affairs ...

Read More +