Introduction

Mountains play a role in the birth and growth of human civilisations. This role is particularly observed with respect to the flow of rivers originating from the mountains, thus earning for these mountains the name, “Water Towers of the World”.[1] In the context of growing water scarcity and the challenges in governance of this resource, the rivers flowing out from the world’s mountains are of global significance.[2] To respond to the challenge of a global water crisis, there is a need for a new approach to water governance replacing the present one which is based on a reductionist paradigm. This new approach will have to be based on holistic, inclusive and integrated knowledge.[3] The need for a shift has become more urgent in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).[4] In 2021, the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) stressed on the urgency of addressing the global water crisis, especially as the impacts of climate change are becoming starker.[5]

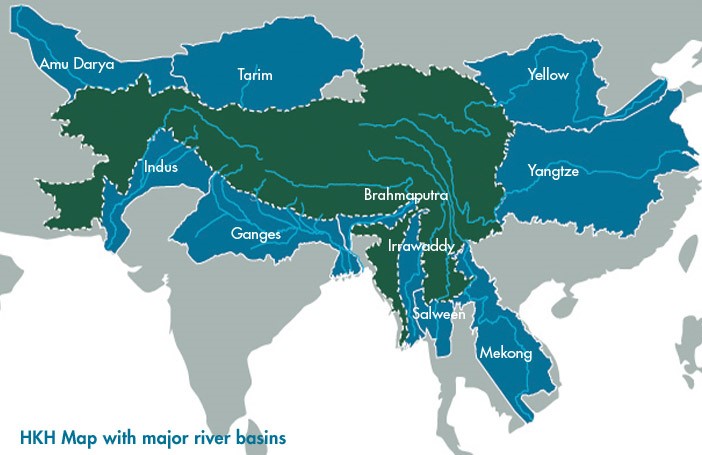

In Central and South Asia, the imperative is clear for the governance of the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH)—a mountain range that stretches 3,500 km and straddles eight countries – Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bhutan, China, Myanmar, Bangladesh. The HKH is the origin of 10 large rivers in Asia that are crucial to the water needs of 16 countries in the region, including large ones such as China and India. For the sheer size of the HKH, and that of the population it serves, these mountains are known as the “Water Tower of Asia”.[6] About 250 million people live within the HKH region itself. The 10 rivers originating in the range flow downstream to the vast plains of Asia and their deltas, serving the livelihood needs of cumulatively 2 billion people.[7] These river basins are: Yellow, Yangtze, Mekong, Salween, Irrawaddy, Brahmaputra, Ganges, Indus, Amu Darya, and Tarim (Figure 1). Their total area is 8.99 million sq. km, of which 2.79 million sq. km lie within the HKH region.[8] This picture of the duality of the uplands and the plains is important; Figure 1 shows their locations.

Figure 1: Basins of the HKH Rivers

Note: Areas outside the HKH region in light blue, and the HKH region in dark green.

Such dependence on the HKH, and the growing demands of freshwater in all the river basins of the HKH, necessitates that it be governed in an informed manner in order to mitigate potential disputes and environmental degradation. The challenge becomes even more acute amidst the impacts of global warming dictating the temporal and spatial flows as well as extreme weather events.

In 1983, the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development was established in Kathmandu, Nepal, to balance environmental preservation and the need for economic activities for poverty reduction in the region.[9] Some years later, following the work of the World Commission on Environment and Development and the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, the principles of “integrated development” and “sustainability” were declared to be intertwined to encompass ecological, social, and economic imperatives.

This report assumes the principle that nature organises itself in a systematic and integrated manner; it is the reductionism that has predominated contemporary governance paradigm that interrupts nature’s systems. To overcome such reductionist thought, for instance for water resources, the imperative is for the creation of a knowledge system that integrates disciplinary knowledge to generate a holistic understanding. This new framework for integration of knowledge system is identified in this study as the System of Integrated Knowledge (SINK).

In the past several decades, integration of knowledge at various levels has been thought of, but the articulation of the steps for integration has not progressed to create any significant impact in practice. SINK provides a new paradigm for the governance of water systems. It draws on other disciplinary knowledge systems, including indigenous/local/traditional knowledge; the creation of new knowledge is taking place largely in specialised areas of research. A dynamic and symbiotic relationship between such realms of disciplinary knowledge will lead to the synthesis of specialised knowledge and the creation of integrated knowledge. Indeed, water governance experts should manage the integrated and inclusive knowledge through a model of a “knowledge pyramid”: the most consolidated and synthesised knowledge is at the top–often characterised as wisdom. This is a complex process in need of greater attention that it has not received so far. As some observers have noted, the lack of dynamic and holistic systems thinking required for the generation of integrated knowledge on water resources is due to two reasons: First, the reward system in academic institutions tends to encourage “traditional” research as they are often easier to get published. Second, funding organisations tend to support projects that are practical and time-bound, rather than those that push for the development of integrated interdisciplinary frameworks which are inherently slower and more uncertain.[10]

In the case of the HKH region—with its environmental fragility, ecological complexity, and dense populations in the foothills and plains where poverty reduction is a priority—the range of integrated knowledge needed for water governance is wide and multi-disciplinary. Further, of the 10 HKH river basins, eight are shared by two or more countries; all the basins are also affected by provincial and sectoral trans-boundary governance challenges.

This report aims to articulate the fundamental aspects of a SINK specific to the HKH. It offers suggestions for a new approach to research and education processes that generate and use SINK and builds the capacity of professionals, political leaders, and policymakers involved in the governance of the HKH basins.

The rest of the monograph is structured as follows. Section 1 outlines a description of the fragile natural environment of the HKH and the atmospheric, geospheric, biospheric, and hydrospheric processes through which the streams and rivers are formed. Section 2 describes the concept of “integrated knowledge” and expands it to cover existing research from other parts of the world that have conceptualised and generated integrated knowledge in different governance domains. The third section then underlines the relevance of integrated knowledge in the governance challenges specific to the 10 HKH river basins. The last section offers a framework and systematic approach to the generation of diverse types of integrated knowledge as part of SINK. The aim is to guide in the design of research and education programmes for advancing SINK in practice in the HKH river basins.

Read the entire report here.

Endnotes

[1]Jayanta Bandyopadhyay, “Water Towers of the World,” People and the Planet (1996) (London)5 (1). https://lib.icimod.org/record/9922

[2] Jayanta Bandyopadhyay et al. “Highland Waters: A Resource of Global Significance,” in Mountains of The World: A Global Priority, ed. Bruno Messerli and Jack D. Ives (New York: Parthenon, 1997), 131–134.

[3] Gro Harlem Brundtland, Foreword to The Global Water Crisis: Addressing an Urgent Security Issue, by Harriet Bigas et al. (Hamilton: UNU-INWEH, 2012), xi–xii.

[4] UNESCO and UNESCO International Centre for Water Security and Sustainable Management, Water security and the sustainable development goals, Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 2012, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3807832?ln=en

[5] World Meteorological Organisation, 2021 State of Climate Services: Water, Geneva: WMO Publications, 2021, https://library.wmo.int/doc_num.php?explnum_id=10826

[6] International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Sustainable Mountain Development 1992, 2012, and Beyond, by Madhav Karki, Kathmandu: ICIMOD, 2012, https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/mountain_partnership/docs/HKH_FINAL_Regional_Report_HKH_29May_0.pdf

[7] P Wester, A Mishra, A Mukherji and A B Shrestha, eds., The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment:

Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People. (Germany: Springer International Publishing, 2019) https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-319-92288-1

[8] International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Sustainable Mountain Development 1992, 2012, and Beyond

[9] N. S. Jodha, A Framework for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, ICIMOD, 1990, https://lib.icimod.org/record/25705/files/attachment_465.pdf?type=primary

[10] Editorial, “Too much and not enough,” Nature Sustainability 4, 659 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00766-8

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV