DEPA promises to be the techno-legal solution that can unlock value in data sharing by giving users more control over their data. This control not only results in increased competition but also fosters innovation. This brief aimed to critique this architecture in its early days to offer suggestions that can improve its workability.

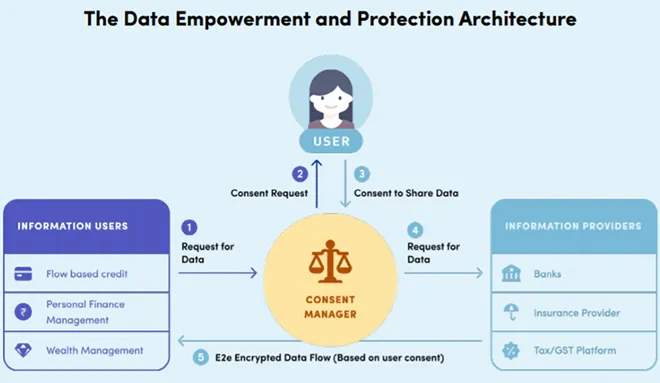

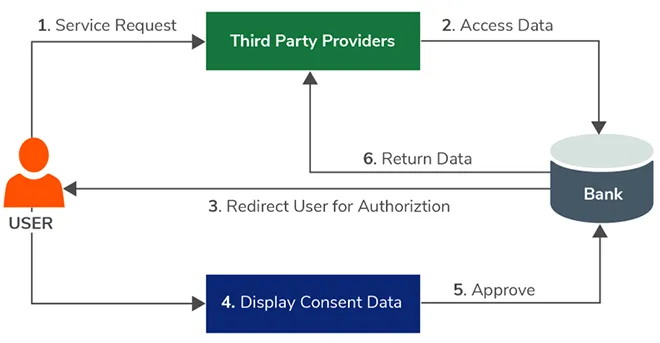

Although DEPA is not a completely new solution, as similar architectures in the form of PIMS or PDS are evolving in the EU, the model needed unpacking because of its technological and legal complexity. Thus, the brief first examined these layers to reveal the conceptual framework behind the architecture. While DEPA can be compared to the Open Banking model in the UK, what sets it apart is the involvement of a Consent Manager that segregates consent and data flow.

The brief then explained the two building blocks of DEPA: data portability and data interoperability. Together these two parts enabled the scrutiny of legal, commercial and institutional aspects of this framework in the last part of the brief.

The broader legislative mandate behind DEPA is enshrined in the right to data portability in the draft Data Protection Bill, 2019. For the widespread use of DEPA, this right should soon be concretised in the form of legislation. The brief also recommends that sub-categories of data involved in data sharing in general and also within the framework of DEPA need to be carefully deliberated. While there may be benefits in sharing of inferred data, it may adversely affect the incentives of firms that invest in inferring data. Similarly, derived data can reveal proprietary company algorithms or techniques and thus may harm a firm if shared with competitors.

Incumbents may not have the right incentives to ensure smooth data sharing, thus they should not be allowed to undertake the role of Consent Managers. Finally, the brief recommends that institutional oversight of the DEPA framework should fall under the Data Protection Authority envisioned in the PDP Bill, 2019. Sectoral regulators, however, can be involved in the standardisation of APIs where the markets cannot take the lead in the standardisations process.

There has been a recognition that DEPA is not a static policy product; rather, it is an “evolvable and agile framework”.[80] This brief has attempted to inform the policy debate on DEPA by explaining the concept to the readers and offering suggestions to policymakers at the same time. Understanding the techno-legal nuances of DEPA and addressing critical issues such as cyber security and operational risks[81] merit further research and discussion.

About the Author

Fellow, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi; Affiliated Research Fellow, Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition, Munich. [email protected]. The author is grateful to Arun Sukumar for very helpful discussions. All views and errors are author’s alone.

Endnotes

[a] Aadhar is the Unique Identification (UID) number issued to all residents of India that serves as proof of identity and proof of address.

[b] Unified Payments Interface (UPI) is an instant payment system developed by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), an RBI-regulated entity. UPI is built over the IMPS infrastructure and allows users to instantly transfer money between any two parties‘ bank accounts.

[c] IndiaStack is a set of APIs that allows governments, businesses, startups and developers to utilise a unique digital infrastructure aimed at “presence-less, paperless, and cashless service delivery.”

[d] APIs (Application Program Interface) are tools that developers and programmers use to create software. They work as a back-and-forth form of information between the user and the institution you are interacting with. For example, when you buy a ticket online, APIs send the information (e.g., credit card details) to the company to transform the data into the final ticket.

[f] The Open Banking webpage lists 109 open banking apps that provide a range of solutions, essentially based on open banking, to users. There is a sufficient degree of competition in this market.

[g] This Working Party was set up under Article 29 of EU Directive 95/46/EC. It is an independent European advisory body on data protection and privacy. Its tasks are described in Article 30 of Directive 95/46/EC and Article 15 of Directive 2002/58/EC.

[1] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion.

[2] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion

[3] Edited by Chandrashekar Srinivasan, ““Health ID For Each Indian”: PM Announces National Digital Health Mission”, NDTV India, August 15, 2020.

[4] Committee of Experts under the Chairmanship of Justice B.N. Srikrishna, “A Free and Fair Digital Economy: Protecting Privacy, Empowering Indians”, page 38.

[5] Hiralal Thanawala, “Here’s how account aggregators share financial data of customers with banks”, Money Control, December 7, 2020, ;

[6] Malvika Raghavan and Anubhutie Singh, “Regulation of information flows as Central Bank functions?: Implications from the treatment of Account Aggregators by the Reserve Bank of India”.

[7] MEDICI, “India’s Open Credit Enablement Network (OCEN)”, February 12, 2021,; iSPIRT, “iSPIRT Second Open House on OCEN: Varied LSP Possibilities”, August 1, 2020.

[8] Sunil Jain, “The West created monopolies, we democratised data: Nandan Nilekani, co-founder, Infosys”, Financial Express, May 21, 2021.

[9] Charles I. Jones and Christopher Tonetti, “Nonrivalry and the Economics of Data”, August 2019, Stanford GSB, Working Paper No. 3716.

[10] The OECD, “Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data: Reconciling Risks and Benefits for Data Re-use across Societies”, page 16.

[11] The OECD, Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data, page 11.

[12] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion

[13] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion

[14] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion

[15] The RBI issued the Account Aggregator (Consent Managers) Directions on September 02, 2016, which was last updated on November 22, 2019.

[16] Sahmati, Sahamati – Collective of the Account Aggregator Ecosystem; for the use cases of the AA model see, BG Mahesh, “Use Cases For Account Aggregator Framework”, Sahamati, 5th December 2020.

[17] Sahamati, Frequently Asked Questions.

[18] Sahamati, Sahamati – Collective of the Account Aggregator Ecosystem.

[19] BG Mahesh, “What is an Informed Consent & Consent Artefact?”, Sahamati, 14th June 2020.

[20] See,MeitY, Electronic Consent Framework, Technology Specifications, Version 1.1, page 7.

[21] Sec 2 (13) of the PDP bill states ‘ “data fiduciary” means any person, including the State, a company, any

juristic entity or any individual who alone or in conjunction with others determines the purpose and means of processing of personal data.”

[22] Sahamati, Sahamati – Collective of the Account Aggregator Ecosystem

[23] Guillaume Brochot, Julianna Brunini, Franco Eisma Rebekah Larsen and Daniel J. Lewis, “Personal Data” Stores, Cambridge Judge Business School, 2015, page 2.

[24] Jan Krämer, Pierre Senellart, Alexandre de Streel, “Making Data Portability More Effective for the Digital Economy: Economic Implications And Regulatory Challenges”, June 2020, CERRE, page 45.

[25] Heleen Janssen, Jennifer Cobbe, Chris Norval and Jatinder Singh, “Decentralized data processing: personal data stores and the GDPR” International Data Privacy Law, 2020, Vol. 10, No. 4.

[26] Serge Abiteboul, Benjamin André, Daniel Kaplan. Managing your digital life with a Personal information

management system. Communications of the ACM, Association for Computing Machinery, 2015, 58 (5), pp.32-35

[27] Opinion 9/2016, EDPS Opinion on Personal Information Management Systems: Towards more user empowerment in managing and processing personal data, 20 October 2016, page 6.

[28] Heleen Janssen, Jennifer Cobbe, Chris Norval and Jatinder Singh, “Decentralized data processing: personal data stores and the GDPR”, p 362.

[29] Jan Krämer, Pierre Senellart, Alexandre de Streel, “Making Data Portability More Effective for the Digital Economy: Economic Implications And Regulatory Challenges”

[30] Jan Krämer, Pierre Senellart, Alexandre de Streel, “Making Data Portability More Effective for the Digital Economy: Economic Implications And Regulatory Challenges”

[31] Opinion 9/2016, EDPS Opinion on Personal Information Management Systems: Towards more user empowerment in managing and processing personal data, page 11.

[32] See, UK Finance, “Payment Services Directive 2 and Open Banking”.

[33] Rowland Manthorpe, “What is Open Banking and PSD2? WIRED explains”, WIRED, April 17, 2018.

[34] Open Banking, “What is Open Banking?”,

[35] The OECD, Data portability, interoperability and digital platform competition – Background Note, DAF/COMP(2021)5.

[36] Open Banking, “What is Open Banking?”

[37] Open Banking, “Three years since PSD2 marked the start of Open Banking, the UK has built a world-leading ecosystem”.

[38] Open Banking, “Three years since PSD2 marked the start of Open Banking, the UK has built a world-leading ecosystem”

[39] Open Banking, “Start your Open Banking Journey”.

[40] Shri M. Rajeshwar Rao, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India, discusses the AA model as an Open Banking solution in his speech.

[41] MeitY, Electronic Consent Framework Technology Specifications, Version 1.1

[42] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion, page 17, also at 36.

[43] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion, page 33.

[44] Sahamati, Frequently Asked Questions

[45] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion, page 28.

[46] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion, page 28.

[47] Prashant Agrawal, Anubhutie Singh, Malavika Raghavan, Subodh Sharma and Subhashis Banerjee, “An operational architecture for privacy-by-design in public service applications” (2020).

[48] Intersoft Consulting, “GDPR: Privacy by Design”.

[49] The UK Information Commissioner’s Office, “Data protection by design and default”.

[50] The European Union Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA), “Privacy and Security in Personal Data Clouds”, Final Report Public, November 2016, page 16.

[51] Article 5 (g) Master Direction- Non-Banking Financial Company – Account Aggregator (Reserve Bank) Directions, 2016.

[52] Article 5(h) Master Direction- Non-Banking Financial Company – Account Aggregator (Reserve Bank) Directions, 2016.

[53] The Royal Society, Privacy Enhancing Technologies, 21 July 2021.

[54] Office of Privacy Commissioner of Canada, “Privacy Enhancing Technologies – A Review of Tools and Techniques”; see also, Data Security Council of India (DSCI), “ Privacy Enhancing Technologies”, https://www.dsci.in/content/privacy-enhancing-technologies

[55] The World Bank, “Unraveling Data’s Gordian Knot: Enabler’s and Safeguards for Trusted Data Sharing in the New Economy”, 2020, page 52.

[56] Vikas Kathuria and Jessica C. Lai, “User review portability: Why and how?”, Computer Law & Security Review

Volume 34, Issue 6, December 2018, Pages 1291-1299.

[57] Jacques Crémer, Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye and Heike Schweitzer, “Competition policy for the digital era”, 2019, European Commision; Jason Furman, Diane Coyle, Amelia Fletcher, Philip Marsden and Derek McAuley “Unlocking digital Competition: Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel”, Crown Copyright, March 2019.

[58] Emerline, “What is a Super App? Reasons for Success?”, Nov 12, 2020.

[59] Satchit Balsari et al, “Reimagining Health Data Exchange: An Application Programming Interface-Enabled Roadmap for India” (2018) 20 (7): July, Journal of Medical Internet Research.

[60] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion.

[61] Reserve Bank Information Technology Pvt. Ltd. (REBIT), Account Aggregator Ecosystem API Specifications.

[62] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion

[63] Reserve Bank of India, Master Direction- Non-Banking Financial Company – Account Aggregator (Reserve Bank) Directions, 2016 (Updated as on November 22, 2019).

[64] Sec 72A of the Information Technology Act, 2000.

[65] Janssen, H. & Cobbe, J. & Singh, J. (2020). “Personal information management systems: a user-centric privacy utopia?” Internet Policy Review, 9(4), page 12.

[66] Explanation to Sec 23 PDP Bill, 2019.

[67] Recital 7 & 68, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

[68] For a taxonomy of different types of data see, OECD, “Summary of the OECD Privacy Expert Roundtable”, DSTI/ICCP/REG(2014)3.

[69]Article 29 Data Protection Working Party, “Guidelines on the right to data portability”, 2016.

[70] https://ec.europa.eu/information_society/newsroom/image/document/2016-51/wp242_en_40852.pdf DEPA as a framework could apply to personal data (data with personally identifying information)

and to derived data (data with masked personally identifiable information but could reveal

confidential data of a company). When sharing the latter, care ought to be taken to maintain a

[71]Article 29 Data Protection Working Party; Article 20 GDPR: “The data subject shall have the right to receive the personal data concerning him or her, which he or she has provided to a controller, in a structured, commonly used and machine-readable format and have the right to transmit those data to another controller without hindrance from the controller to which the personal data have been provided”

[72] Diana Lee, Gabe Maldoff and Kurt Wimmer, “Comparison: Indian Personal Data Protection Bill 2019 vs. GDPR”, IAPP; Aditi Agrawal, “A lowdown on Personal Data Protection Bill 2019”, Forbes India, Jan 28, 2021.

[73] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion, page 36-37.

[74] OECD, Data portability, interoperability and digital platform competition – Background Note, DAF/COMP(2021)5, page 11.

[75] CASE AT.39740 Google Search (Shopping) European Commision; CASE AT.40099 Google Android.

[76] Sec 5 (f) Master Direction- Non-Banking Financial Company – Account Aggregator (Reserve Bank) Directions, 2016.

[77] Malvika Raghavan and Anubhutie Singh, “Regulation of information flows as Central Bank functions? Implications from the treatment of Account Aggregators by the Reserve Bank of India”

[78] See, Michal Gal and Daniel L Rubinfeld, “Data Standardization”, (June 2019). 94 NYU Law Review (2019) Forthcoming, NYU Law and Economics Research Paper No. 19-17. The authors highlight the reasons for which government in some cases can play an important role in standardization.

[79] Michal Gal and Daniel L Rubinfeld, “Data Standardization”

[80] NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture, Draft for Discussion

[81] RBI, Opean Banking in India, Remarks by Shri M. Rajeshwar Rao, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India – Wednesday, April 14, 2021 – in a webinar on Open Banking organised by Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) in association with the Embassy of India in Brazil.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV