-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Kashish Parpiani, “Cultivating the Bipartisan Consensus on India in the 116th US Congress”, ORF Occasional Paper No. 225, November 2019, Observer Research Foundation.

The Trump era has witnessed a rise in conflict between the executive and legislative branches of the US government. As the foreign-policy conduct of President Donald Trump’s administration continues to cause discomfort amongst allies, analysts and the media, American legislators have stepped in to stem the tide against the transactionalism that is putting to test some of the most fundamental tenets of US foreign policy. With the locus of foreign policy decision-making shifting away from the Oval Office and towards the Capitol Hill, US legislators are now seeking to curb many of Trump’s powers on a range of issues, such as troop withdrawals, initiating US retreat from crucial alliances, and off-ramping punitive sanctions against adversarial nations.

This struggle between the White House and the US Congress on foreign policy has now reached unprecedented levels. As a result, studying the US Congress’ role in American international relations has assumed renewed relevance. For India, a recent case in point is the Congressional hearing on human rights in South Asia, where the Democrat-controlled US House of Representatives initiated discussions on the Trump administration’s support for India’s abrogation of Article 370 in Kashmir—a topic that dominated the hearing.

As India’s bilateral dynamic with the US moves towards a more consultative format—away from the erstwhile dependence on the personal rapport between top-level political leaders—the US Congress has become all the more crucial. Largely underpinned by the thriving Indian-American diaspora in the US, American legislators from either side of the political aisle have often found common ground on US interests to cultivate India as a strategic partner. This has been in the context of either a shared commitment to democratic values or common threat perceptions regarding emerging powers such as China. Consequently, the Congressional Caucus on India and Indian Americans in the US House of Representatives is the largest such cobbling of lawmakers. The India Caucus in the US Senate, meanwhile, is notably the first country-specific caucus of the chamber.

Unfortunately, the impact of this bipartisan consensus in the development of contemporary US–India strategic ties over the years has received little attention.

In the post-Cold War era, a roadblock to the US and India realising their potential for strategic cooperation was the former’s insistence on treating India as an outcast due to its nuclear programme. For instance, the US imposed sanctions on India following the latter’s nuclear test in 1998.[1] Over time, however, the US shifted its perceptions as India displayed economic potential with liberalisation reforms. Indeed, Prime Minister Atal B. Vajpayee, on a historic visit to the US characterised the two countries as “natural allies”.[2]

In recent years, with China’s rapid rise, the US has come to view India from a more strategic standpoint. An early sign of this was seen in the highly contentious presidential campaign of 2000. As the Republican nominee, then-Governor George W. Bush sought to attribute the foreign-policy failures of the William Clinton administration to Clinton’s vice-president, Al Gore – Bush’s Democratic opponent for the presidency. The Bush campaign made rallying points around Clinton’s “Engagement and Enlargement” grand strategy of seeking American “security by protecting, consolidating and enlarging the community of free market democracies.”[3]

However, a point of continuity emerged over courting India, due to its “success as the largest democracy and its potential as a major emerging economy that embraced globalisation.”[4] By then, relations had already begun to improve, with Clinton’s visit to India in 2000 being the first by a US president since that of Jimmy Carter in 1978.[5] The US had eased technical sanctions, and the Clinton administration had moved away from the Pakistan-centric US South Asia policy under Assistant Secretary of State for South Asia Robin Raphel.[6] The Bush campaign sought to build on this and viewed India “through the strategic lens of the need to preserve American hegemony from potentially being challenged by a rising China.”[7] Notably, Bush’s senior campaign adviser, and later US secretary of state (2005–2009), Condoleezza Rice wrote at that time, “… India is an element in China’s calculation, and it should be in America’s, too. India is not a great power yet, but it has the potential to emerge as one.”[8]

This beginning of a tilt towards India did not occur overnight. For nearly a decade before the Bush “calculation” on India, the US Congress had been testing waters with the creation of the Congressional Caucus on India and Indian Americans in the House of Representatives. Formed in 1993, this Congressional Caucus brought together a handful of bipartisan House representatives to advocate “the interests of the more than two million Americans in the United States who were born in India or are of Indian ancestry, and promote and strengthen relations between the United States, the world’s oldest democracy, and India, the world’s largest democracy.”[9] It expanded from its original roster of eight House representatives, to 50 in the first year of its founding. Within a decade, it had over 200 members.[10]

The Caucus initially introduced largely symbolic House Resolutions, such as, “H.Res.227 – Recognizing and honoring the contributions of Indian Americans to economic innovation and society generally;”[11] “H.Con.Res.264 – Expressing the sense of Congress to welcome the Prime Minister of India, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, on the occasion of his visit to the United States, and to affirm that India is a valued friend and partner and an important ally in the campaign against international terrorism;”[12] and “H.Res.562 – Expressing the sense of the House of Representatives that a postage stamp should be issued in commemoration of Diwali, a festival celebrated by people of Indian origin.”[13]

Subsequently, these actions assumed heightened vigour, with the creation of the India Caucus in the US Senate, the upper chamber of the US legislature. Established in 2004 by Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) and Sen. Hillary Clinton (D-NY), who would later become secretary of state (2009–13), it was the first country-focused caucus established in the Senate.[14] With its formation coinciding with the post-9/11 push of the Bush administration to court democratic partners, the stage was set for more concrete actions on strategic matters at the Capitol Hill.

Thus, even as the US and India were slowly inching towards negotiating the India–US Civil Nuclear Agreement, which would essentially end the US’ “nuclear apartheid”[15] against India, the US Congress was at the forefront of testing the waters for an American strategic partnership with India.

| Table 1: Key Congressional Actions on US–India Strategic Ties | ||||

| Yr. | Bill / Amendment/ Sense of Chamber / Resolution |

Status | Co/Sponsored by past/current House/Senate India Caucus member | Significance |

| 2005 | S.1886 – Naval Vessels Transfer Act of 2005 | Passed both chambers, and signed into law by the president |

Bipartisan co-sponsorship by Sen. Richard Lugar (R-IN) and Sen. Joseph Biden Jr. (D-DE) | Led to India’s acquisition of the first US-built warship, the Austin-class amphibious transport dock ship Trenton.[16] Commissioned into the Indian Navy as INS Jalashva.[17] |

| 2006 | H.R.5682 – Henry J. Hyde United States and India Nuclear Cooperation Promotion Act of 2006 | Passed both chambers, and signed into law by the president |

Yes Bipartisan co-sponsorship by Rep. Eliot Engel (D-NY-17) and Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL-18) |

Instituted exemptions for India under the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, towards the India–US Civil Nuclear Agreement.[18] |

| 2008 | H.R.7081 – United States–India Nuclear Cooperation Approval and Nonproliferation Enhancement Act | Passed both chambers, and signed into law by the president |

Yes Sponsored by Rep. Howard L. Berman (D-CA-28) |

Approved “the United States-India Agreement for Cooperation on Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy,” and strengthened US “Nonproliferation Law Relating to Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation.” [19] |

| 2010 | S.3847 – Security Cooperation Act of 2010 | Passed both chambers, and signed into law by the president |

Sponsored by the senior US Senator (D-MA) and subsequently the US Secretary of State John Kerry | Although the transfer did not materialise, it authorised the president to transfer to India on “a grant basis” the Osprey class “minehunter coastal ships Cormorant and Kingfisher.” [20] |

| 2016 | H.R.4825 – U.S.–India Defense Technology and Partnership Act | Introduced, referred to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs |

Yes Sponsored by Rep. George Holding (R-NC-13) |

Directed the president to “take action to formalize India’s status as a U.S. major partner” to “extend special foreign military sales status to India.” [21] |

| 2016 | H.R.5387 – Special Global Partnership with India Act of 2016 | Introduced; referred to the House Subcommittee on Trade |

Yes Sponsored by Rep. Eliot Engel (D-NY-16) |

Called on the president to “make India eligible for the strategic trade authorization exemption from having to obtain certain export control licenses.” [22] |

| 2018 | H.R.5515 – John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 | Passed both chambers, and signed into law by the president |

Yes Co-sponsored by Rep. Adam Smith (D-WA-9) |

Redesignated the Southeast Asia Maritime Security Initiative to the Indo-Pacific Maritime Security Initiative, to now also include India as a fund-recipient country. Instituted modified waiver authority under Section 231 of the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act.[23] |

| 2019 | H.R.2123 – United States–India Enhanced Cooperation Act of 2019 | Introduced; referred to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs |

Yes Sponsored by Rep. Joe Wilson (R-SC-2) |

Builds on H.R. 4825 to elevate the status of India on par with a “NATO ally,” for the purposes of the Arms Export Control Act.[24] |

One such step was the Naval Vessels Transfer Act of 2005, co-sponsored by Sen. Richard Lugar (R-IN) and Sen. Joseph Biden Jr. (D-DE), who subsequently became the US vice-president (2009–17). The Act was significant, as it led to India’s acquisition of the first US-built warship: the Austin-class amphibious transport dock ship, Trenton. Being co-sponsored by the senior bipartisan pair of Lugar and Biden ensured wide acceptability of the Act and set the ball rolling on the normalisation of the US’ strategic tilt towards India. Thereafter, House India Caucus members, such as Rep. Eliot Engel (D-NY-17) and Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL-18), led the way on the formalisation of the civil nuclear agreement, encompassing a crucial amendment to the Atomic Energy Act of 1954.

Under President Barack Obama, the pace of such strategic developments slowed down momentarily. As Obama grappled with the financial crisis and the two inherited wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the US Congress faced gridlock on account of rabid partisanship spurred by Tea Party conservatism. However, the Obama administration continued developing the strategic dynamic with India through intergovernmental actions such as the Defence Technology and Trade Initiative (DTTI), and defence interoperability agreements. Additionally, the Obama administration’s “Pivot to Asia” policy underscored India’s relevance, with Obama becoming the first US president to visit India twice during his tenure of two terms.

Under Trump, as the US Congress assumed a greater role in foreign-policy decision-making, a renewed vigour has become apparent with India Caucus-led Congressional actions. Rep. George Holding (R-NC-13) and Rep. Eliot Engel (D-NY-16) have introduced two legislations pertaining to special authorisations for India on US arms exports (See Table 1). In both cases, even as those legislations make their way through the legislative process, the Trump administration has enacted their prescriptions to grant India the status of “Major Defence Partner” and the Strategic Trade Authorisation-I (STA-I) clearance on purchasing licence-free space and defence technology. Meanwhile, in the context of US arms exports, the legislation introduced by Rep. Joe Wilson (R-SC-2) seeks to elevate India to a status on par with NATO allies. Some India Caucus members, e.g. Adam Smith (D-WA-9), have also led the way (in a bipartisan manner) against Trumpian transactionalism. An example of this is the 2018 passage of modified waiver provision for India against US sanctions, under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA).

In 1787, Thomas Jefferson wrote: “My idea is that we should be made one nation in every case concerning foreign affairs, and separate ones in what is merely domestic.”[25] At varied points in the course of American foreign policy, the relevance of this idea has been apparent: from the state-directed effort to muster the “arsenal of democracy”[26] in the run-up to World War II, to the initial popular support for US’ “responsibility” and “privilege to fight freedom’s fight”[27] in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. Even in large parts through the Cold War, some core tenets of US foreign and security policy remained guarded under bipartisan vigour. For instance, unwavering US support for “special relationships,” e.g. with the UK or Japan, and Washington’s stewardship of liberal Wilsonian values were deemed as matters of partisanship stopping at the “water’s edge.”[28] In recent years, however, that Jeffersonian dictum has been under attack from intense political polarisation. The declining currency of liberal internationalism due to the rising support for Jacksonian populism, which abhors US activism abroad, has brought into question the US’ traditional stewardship of the liberal world order.

The political faultlines in America that once plagued mostly domestic issues, such as gun control, immigration reform and universal healthcare, have now seeped into matters pertaining to foreign policy. The isolationist tendencies of conservative nationalism, emblematic in the rise of Donald Trump, brings into question the efficacy of the US extending its security umbrella over allies that have supposedly “taken advantage”[29] of America by accumulating large trade surpluses. Moreover, support for US activism abroad seems to have declined as the US has engaged in expansive nation-building operations abroad, even as its own infrastructure is deemed to be “crumbling”[30] and legislative resolution on domestic contentions such as gun control and immigration continue to be stalled amidst rising partisanship.

Therefore, the once-fundamental tenets that informed the US’ role in the world are being challenged as the centre of gravity of the Republican and Democratic parties shift further into either’s populist corners. For example, the emerging faultline over the US’ support for Israel, wherein the more “progressive” faction of the Democratic Party has shed light on the overt influence of the Jewish lobbies over US foreign policy.[31] Similarly, some senior Republicans have expressed ambivalence towards Trump’s embrace of “strongman leaders” around the world, thus espousing a point of contention over the US’ erstwhile stewardship of liberal democracies.[32]

In contrast, support for the evolving US–India dynamic—and for India, by extension—remains a point of convergence for Republicans and Democrats on the Hill. This is evident in the heightened role of the US Congress and in Caucus members championing US–India strategic ties.

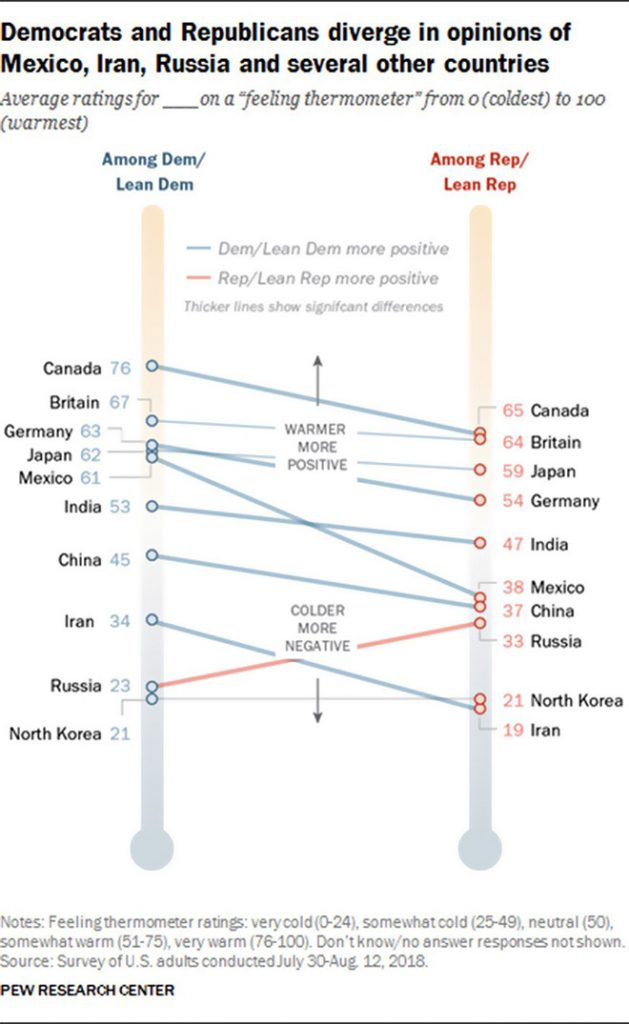

Three major factors explain the rising support for India despite intense polarisation. First, the US–India dynamic is unique, exempting India from much of the ire of conservative nationalists. In recent years, building on the shared democratic values between India and the US, the two nations have witnessed a steady development of strategic ties, especially in the realms of defence trade and force interoperability. This, despite India being a non-formal treaty partner of the US. Moreover, India’s continued quest for strategic autonomy—stemming from its non-aligned impulses—gives its dynamic with the US a unique character, devoid of alliance compulsions. Conservative nationalism dictates settling scores with allies who have benefitted from the US’ “70-odd year-period of largesse;”[33] this does not include New Delhi due to its lack of overt dependence on Washington. According to a late 2018 PEW poll,[34] India does not figure as high on the Democrats’ positive views as do treaty allies such as Canada or the United Kingdom; at the same time, it also does not figure prominently on the Republicans’ negative views towards US adversaries, as do North Korea or Iran (See Figure 1). Thus, India enjoys moderate to slightly favourable views amongst both parties. In the context of bipartisanship, apart from treaty allies Japan and the UK, India is the only country to have the narrowest divide between Democratic and Republican favourability ratings. Another poll by the Chicago Council found the divide between Republicans and Democrats on the desirability for India to “exert strong leadership in world affairs” to be “just five points.”[35]

Figure 1 – Partisan Divides in Views of Countries

Source: PEW research poll

This convergence away from the parties’ past contention over the ideal approach—liberal internationalists’ engagement versus neoconservatives’ containment prescriptions—towards China has greatly contributed to the elevation of India’s significance. For instance, the Indo-Pacific strategy against Chinese grand strategic propositions, e.g. the Belt and Road Initiative, places special emphasis on Washington “building new and stronger bonds with nations that share our values across the region,” such as India.[38] India’s centrality in the US’ regional calculus is evident not only in the heightened adoption of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ moniker but also in the strategy’s fundamental goal to link the destiny of the Indian Ocean Region to that of Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific at-large.

Third, the influence of Indian-Americans on Capitol Hill and on America’s societal fabric has increased in recent years. The population of Indian-American diaspora has grown to nearly four million,[39] and they have emerged amongst the “richest ethnic communities” in America, with a median annual income of “approximately $89,000 which is far higher than the median annual income of the U.S. national at $50,000.”[40] Moreover, Indians accounted for 17.9 percent of America’s total foreign students in 2017–18, effectively contributing US$7.5 billion to the US economy.[41] Finally, the rise of Indian-American legislators—known for their support for greater US engagement with India—to prominent positions consolidates the discussed bipartisan consensus. Some examples include Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA) of the House Armed Services Subcommittees on Intelligence and Emerging Threats and Strategic Forces[42] and Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) of the Congressional Progressive Caucus.[43] These factors raise the social consciousness on India and add to its influence amongst US legislators on the Hill.

The sustained consensus on India has already been seminal to the evolving dynamic of US–India relations. The US and India have had “convivial ties develop between Clinton and Vajpayee (a Democrat and BJP PM), Bush and Vajpayee (Republican and BJP PM), Bush and Dr. Manmohan Singh (a Republican and a Congress PM), Obama and Dr. Singh (a Democrat and a Congress PM), Obama and Modi (Democrat and BJP) and now between Trump and Modi (Republican and BJP PM).”[44] India must now take advantage of this unique bipartisan support, especially in these polarised times in the US. Going forward, India must adopt a pointed approach to not only further cultivate this consensus but also use it to generate policy outcomes that benefit India.

In early 2019, the Trump administration informed the US Congress of its intent to suspend India’s designation as a beneficiary developing country under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) programme. According to 2017 statistics, India was the largest beneficiary of the GSP, with a substantial portion of its goods enjoying duty-free access into the US. Its estimated value is US$5.7 billion, i.e. over 12 percent of all Indian exports to the US in 2017.[45] The drive to suspend India’s GSP status stemmed from the continued stalling of trade negotiations, now in its second year.

The timing of the announcement bore ominous prospects for the incumbent Modi government, as India was entering its general elections season. Acknowledging the potential impact, Rep. George Holding (R-NC), the co-chair of the Congressional Caucus on India and Indian Americans, reportedly wrote to the US Trade Representative to “postpone the termination of India’s GSP eligibility and revisit this decision after India’s general election.”[46] Similarly, the co-chairs of the Senate India Caucus Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) and Mark Warner (D-VA) urged to “consider delaying” the suspension of India’s GSP status,[47] warning of its counterintuitive effects. They wrote, “While we agree that there are a number of market access issues that can and should be addressed, we do remain concerned that the withdrawal of duty concessions will make Indian exports of eligible products to the United States costlier, as the importer of those products will have to pay a ‘Most Favoured Nation’ (MFN) duty which is higher than the rate under GSP.”[48] Although tempers briefly cooled in the Trump administration, India’s GSP status was suspended right after the general elections ended.[49] The action not only had counterintuitive ramifications as predicted by Cornyn and Warner but also presented challenges with regards to the Trump administration’s broader “trade war” with China.

According to a report by the Coalition for GSP (a group of American companies and trade associations) as US imports from China decreased—under Section 301 tariffs—imports of some of those very products from GSP-status countries “increased the most in the first quarter of 2019.”[50] On India, the report noted that “97 percent of increased 2019 GSP imports” were for the products on the China Section 301 sanctions list. In figures, US imports from India of Section 301 products “increased by USD 193 million (18 percent).”[51] The report also warned against terminating GSP status for countries such as India, as it would not only “hurt many American companies and workers that have relied on GSP for years, it would also reduce viable sourcing options for companies looking to buy less from China in response to Section 301 tariffs – thereby undermining the President’s own objectives.”[52]

The Trump administration’s follow-through on the suspension reflected its disregard for the strategic relevance of India’s GSP status to the US’ own goals. Moreover, the action even stood in opposition to the US Congress’ 2018 reauthorisation (with unprecedented unanimity) of the GSP programme for another three years.[53] In many such cases of counterintuitive ramifications on US interests, the Congress has stepped in to correct the course of Trump’s foreign policy via amendments and/or stop-gap provisions to existing legislations. In India’s GSP case, however, it only led to the mere postponement of the decision until the Indian elections were through. An argument can be made that the reason behind the lack of more concrete action could have been the limited influence of the House and Senate India Caucuses amongst the foreign-policy legislators of the current 116th US Congress.

Going forward, to ensure the translation of its wide influence on Capitol Hill into concrete policy results in accordance with its interests (as well as the US’ interests, as in the GSP case), India must adopt a pointed approach in its engagement with the US Congress. To further raise the consciousness on India’s strategic value beyond the India caucuses, New Delhi must pay particular attention to the ordering of the House Foreign Affairs Committee (HFAC) and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (SFRC). The HFAC and SFRC are the central platforms on the Hill, where the US’ worldview is devised, informed and, at times, even corrected through concurrent amendments and legislations. Relative to other committees such as the Armed Services Committee, the foreign-affairs committees have an expansive purview over varied matters pertaining to an administration’s foreign-policy conduct: aid dispensation, arms sales, trade authorisations, and more specificities via region- and issue-based subcommittees.

Recent reports have suggested that the Trump administration had been contemplating country-specific caps for India on H1-B visas as a bargaining chip. The administration considered capping the H1-B visas to 15 percent for any country that “does data localisation.”[54] This bore “ominous prospects for India’s $150 billion IT sector as 70 percent of the 85,000 H1B visas issued every year go to Indians.”[55] With the Trump administration linking issues across domains to achieve policy goals, the potential purview of HFAC and SFRC stands enhanced.[56] Consequently, they are best equipped to probe and possibly correct decisions that cut across multiple domains of American foreign policy, e.g. India’s GSP issue.

However, the current ordering of the HFAC and SFRC reflects a limited presence of House and Senate India Caucus members. Consider Table 2 on the HFAC and its “Subcommittee on Asia, The Pacific, and Non-proliferation,” which has purview over matters pertaining to India. Out of 47 committee members, a bipartisan mix of about 10 are known current or past members of the House’s Congressional Caucus on India and Indian Americans. While that number includes influential members such as the Chair of the HFAC Rep. Eliot Engel (D-NY-16), the fact remains that committees function on the principle of one member, one vote. On the subcommittee, only two out of 10 members are known current or past members of the House’s Congressional Caucus on India and Indian Americans. Moreover, both those members—Rep. Ami Bera (D-CA-07) and Rep. Brad Sherman (D-CA-30)—are Democrats hailing from the state of California, which may limit broad consensus.

India needs to step up efforts to cultivate HFAC legislators that are not India Caucus members, many of whom represent states that are home to sizable populations of Indian Americans, such as Texas, California, New Jersey, New York, Florida and Illinois.

| Table 2: 116th Congress–US House Committee on Foreign Affairs [57] | |||||

| Sr. no | Representative | Party | Congressional District | Subcommittee on Asia, The Pacific, And Non-proliferation [58] | Current/Former Member of House India Caucus |

| 1 | Eliot Engel (Chairman) | D | New York – 16 | – | Yes[59] |

| 2 | Michael McCaul (Ranking Member) | R | Texas – 10 | – | No |

| 3 | Brad Sherman | D | California – 30 | Yes (Chairman) | Yes[60] |

| 4 | Christopher Smith | R | New Jersey – 4 | – | No |

| 5 | Gregory Meeks | D | New York – 5 | – | No |

| 6 | Steve Chabot | R | Ohio – 1 | – | Yes[61] |

| 7 | Albio Sires | D | New Jersey – 8 | – | Yes[62] |

| 8 | Joe Wilson | R | South Carolina – 2 | – | Yes[63] |

| 9 | Gerald Connolly | D | Virginia – 11 | Yes | No |

| 10 | Scott Perry | R | Pennsylvania – 10 | Yes | No |

| 11 | Theodore Deutch | D | Florida – 22 | – | No |

| 12 | Ted Yoho | R | Florida – 3 | Yes (Ranking Member) | No |

| 13 | Karen Bass | D | California – 37 | – | No |

| 14 | Adam Kinzinger | R | Illinois – 16 | – | No |

| 15 | William Keating | D | Massachusetts – 9 | – | No |

| 16 | Lee Zeldin | R | New York – 1 | – | No |

| 17 | David Cicilline | D | Rhode Island – 1 | – | No |

| 18 | Jim Sensenbrenner | R | Wisconsin – 5 | – | No |

| 19 | Ami Bera | D | California – 7 | Yes | Yes[64] |

| 20 | Ann Wagner | R | Missouri – 2 | Yes | No |

| 21 | Joaquin Castro | D | Texas – 20 | – | Yes[65] |

| 22 | Brian Mast | R | Florida – 18 | Yes | No |

| 23 | Dina Titus | D | Nevada – 1 | Yes | No |

| 24 | Francis Rooney | R | Florida – 19 | – | No |

| 25 | Adriano Espaillat | D | New York – 13 | – | No |

| 26 | Brian Fitzpatrick | R | Pennsylvania – 1 | – | Yes[66] |

| 27 | Ted Lieu | D | California – 33 | – | Yes[67] |

| 28 | John Curtis | R | Utah – 3 | Yes | No |

| 29 | Susan Wild | D | Pennsylvania – 7 | – | No |

| 30 | Ken Buck | R | Colorado – 4 | – | No |

| 31 | Dean Phillips | D | Minnesota – 3 | – | No |

| 32 | Ron Wright | R | Texas – 6 | – | No |

| 33 | Ilhan Omar | D | Minnesota – 5 | – | No |

| 34 | Guy Reschenthaler | R | Pennsylvania – 14 | – | No |

| 35 | Colin Allred | D | Texas – 32 | – | No |

| 36 | Tim Burchett | R | Tennessee – 2 | – | No |

| 37 | Andy Levin | D | Michigan – 9 | Yes | Unclear |

| 38 | Greg Pence | R | Indiana – 6 | – | Unclear |

| 39 | Abigail Spanberger | D | Virginia – 7 | Yes | No |

| 40 | Steve Watkins | R | Kansas – 2 | – | Unclear |

| 41 | Chrissy Houlahan | D | Pennsylvania – 6 | Yes | Unclear |

| 42 | Mike Guest | R | Mississippi – 3 | – | No |

| 43 | Tom Malinowski | D | New Jersey – 7 | – | Unclear |

| 44 | David Trone | D | Maryland – 6 | – | No |

| 45 | Jim Costa | D | California – 16 | – | Yes[68] |

| 46 | Juan Vargas | D | California – 51 | – | No |

| 47 | Vicente Gonzalez | D | Texas – 15 | – | No |

Consider Table 3 on the SFRC and its “Subcommittee on Near East, South Asia, Central Asia and Counterterrorism.” Out of 22 Committee members, about nine— of which seven are Democrats—are known current or past members of the Senate’s India Caucus. Prominent Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham is in this list of nine, which raises bipartisan points and relevance due to his proximity to President Trump on defence issues. In the case of the subcommittee, at least five out of the nine members are known current or past members of the Senate’s India Caucus. However, with most of them being Democrats, bipartisan consensus may be impeded due to the Republicans’ control of the US Senate. India must cultivate prominent Republican foreign-policy voices such as Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) and Marco Rubio (R-FL).

| Table 3: 116th Congress–US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations [69] | |||||

| Sr. no | Senator | Party | State | Subcommittee on Near East, South Asia, Central Asia, And Counterterrorism [70] | Current/Former Member of Senate India Caucus |

| 1 | James E. Risch (Chairman) | R | Idaho | – | No |

| 2 | Robert Menendez (Ranking Member) | D | New Jersey | – | Yes[71] |

| 3 | Marco Rubio | R | Florida | – | No |

| 4 | Ben Cardin | D | Maryland | Yes | No |

| 5 | Ron Johnson | R | Wisconsin | – | No |

| 6 | Jeanne Shaheen | D | New Hampshire | Yes | Yes[72] |

| 7 | Cory Gardner | R | Colorado | Yes | Yes[73] |

| 8 | Christopher Coons | D | Delaware | – | Yes[74] |

| 9 | Mitt Romney | R | Utah | Yes (Chairman) | Unclear[75] |

| 10 | Tom Udall | D | New Mexico | – | No |

| 11 | Lindsey Graham | R | South Carolina | Yes | Yes[76] |

| 12 | Christopher Murphy | D | Connecticut | Yes (Ranking Member) | Yes[77] |

| 13 | Johnny Isakson | R | Georgia | – | No |

| 14 | Tim Kaine | D | Virginia | Yes | Yes[78] |

| 15 | John Barrasso | R | Wyoming | – | No |

| 16 | Edward J. Markey | D | Massachusetts | – | No |

| 17 | Rob Portman | R | Ohio | – | No |

| 18 | Jeff Merkley | D | Oregon | – | Yes[79] |

| 19 | Rand Paul | R | Kentucky | Yes | No |

| 20 | Cory Booker | D | New Jersey | – | Yes[80] |

| 21 | Todd Young | R | Indiana | – | No |

| 22 | Ted Cruz | R | Texas | Yes | No |

In addition to having oversight powers, the HFAC and the SFRC are important for some of India’s other interests pertaining to its ties with the US. Under Trump, the HFAC in the Democrat-led House of Representatives is perhaps the only committee that isn’t plagued by other partisan issues, e.g. Trump’s possible obstruction of justice on the Mueller investigation or the probe into Trump’s alleged strong-arming of Ukraine to investigate presidential-hopeful and Democrat-front runner Joe Biden. Moreover, the HFAC now enjoys a degree of bipartisanship given the Republicans’ understated “concerns with Trump’s foreign policy decisions and his posture on the world stage.”[81] Thus, it can be a crucial bipartisan platform for India to tap into, for instance, with respect to its purview over the State Department’s Political-Military Affairs (PM) Bureau. It is the PM Bureau that “advances the defense trade relationship and broader security partnership between the United States and India.”[82] Specifically, the PM Bureau is the nodal department that facilitates both tracks of US arms exports: the Foreign Military Sales and Direct Commercial Sales processes. India has a crucial stake in ensuring that transactionalism does not raid ongoing processes over the acquisition of the MTCR Category-1 Unmanned Aerial System Sea Guardian drones, and the multi-role MH-60R Seahawk maritime helicopters.

The SFRC is equally important due to its role in confirming State Department nominations for crucial positions such as the US Ambassador to India and Assistant Secretary for South and Central Asian Affairs; the latter remains unfilled till date.[83] Recently, the US Congress amended section 1292 of the NDAA for FY2017 in the “H.R.5515 – John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019,” to mandate the executive to submit annual reports on Indo-US defence interoperability. The SFRC would be the ideal platform for New Delhi to have the legislature mandate an annual report from the executive on the US–India Defense Technology and Trade Initiative, possibly by a perfecting amendment to an upcoming resolution.[84] It is in India’s interest to seek the Congress’ intervention on ongoing issues in the workings of the DTTI, e.g. the abrupt downsizing of the India Rapid Reaction Cell at the Pentagon in 2018.

It is commendable that the executive has taken the lead to put into action the Major Defence Partner status and STA-I for India. However, through intense engagement with the HFAC and SFRC, India must ensure that those designations are grounded in legislative precedents. Their institutionalisation in legislations will go a long away in building a stable trajectory of US–India defence ties, protecting India against the idiosyncrasies of the incumbent executive administration.

Many of the challenges currently facing US–India ties stem from the overt dependence on a top-heavy approach to the dynamic. In the past, this approach of reliance on the personal dynamics between the respective heads of government was crucial to wade through conflictual points such as the US’ opposition to India’s nuclear programme. Today, however, US–India ties have assumed a multidimensional character, from bilateral trade now rapidly inching towards the US$150-billion mark to India conducting most of its military exercises with the US. This merits more champions of greater ties between the two countries on multiple levels.[85]

There is a result-oriented precedent to this. For instance, the active cabinet-level relationship between former Secretary of Defence Ashton Carter and then-Raksha Mantri Manohar Parrikar spurred the swift development of the US–India Defence Technology and Trade Initiative. Thus, going forward, consultative platforms such as the one between the respective heads of foreign and defence departments, i.e. the US–India 2+2 dialogue, are likely to lead the cultivation of bilateral ties.

Moreover, as the US Congress assumes a greater role in the US’ foreign policy decision-making, and India continues to be a point of convergence amidst intense polarisation on the Hill, New Delhi must promote such ties with the US legislature. In the recent past, at least on two occasions (2007[86] and 2009[87]), Jim McDermott (D-WA-7) introduced the “US–India Interparliamentary Exchange Act,” to institute a practice of delegations from the US Congress annually meeting with representatives of the Parliament of India. While the resolution never came up for a vote, and McDermott is no longer in public service, India and the US could carry forward McDermott’s legacy.

There is an urgent need for India to nurture the bipartisan fervour regarding US–India ties on the Hill. At the recent Congressional hearings on Kashmir, US bipartisan support for India came under threat of partisan politics, as Democrats criticised Trump’s ambivalence on India’s communications lockdown in Kashmir and Republicans dampened criticism of Trump by making a case against a values-centric US foreign policy.[88] This was due to the bipartisan consensus on US foreign policy fracturing in recent years, and President Trump’s transactional foreign-policy conduct emerging as the lead contention for the Democrat-led impeachment proceedings. Amidst this highly divergent environment, New Delhi must not only strive to ensure the US’ continued bipartisan support but also seek greater representation in the foreign-policy establishment of the 116th Congress.

[1] Raymond E Vickery Jr., “Looking Back: The 1998 Nuclear Wake Up Call for US-India Ties,” The Diplomat, 31 May 2018, accessed 05 November 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2018/05/looking-back-the-1998-nuclear-wake-up-call-for-us-india-ties/

[2] Malini Parthasarathy, “India, U.S. natural allies: Vajpayee,” The Hindu, 09 September 2000, accessed 02 June 2019, https://www.thehindu.com/2000/09/09/stories/01090005.htm

[3] NSS 1995, “A National Security Strategy Of Engagement And Enlargement,” The White House – President William J. Clinton archives, February 1995, pg. 7, accessed 09 June 2019, http://nssarchive.us/NSSR/1995.pdf

[4] Srinath Raghavan, The Most Dangerous Place – A History of the United States in South Asia, 2018, India: Penguin Random House, pg. 354

[5] PTI report, “US ignored India for 22 years; Clinton visit changed all: Chatwal,” The Economic Times, 14 April 2010, accessed 05 June 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/us-ignored-india-for-22-years-clinton-visit-changed-all-chatwal/articleshow/5805015.cms?from=mdr

[6] Suhasini Haidar, “Robin Raphel, the ‘obstacle’ in India-U.S. ties,” The Hindu, 08 November 2014, accessed 05 November 2019, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/robin-raphel-the-obstacle-in-indiaus-ties/article6575604.ece

[7] Srinath Raghavan, The Most Dangerous Place – A History of the United States in South Asia, 2018, India: Penguin Random House, pg. 354

[8] Condoleezza Rice, “Campaign 2000: Promoting the National Interest,” Foreign Affairs, 01 January 2000, accessed 04 June 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2000-01-01/campaign-2000-promoting-national-interest

[9] IAFC, “Congressional Caucus on India and Indian Americans,” The Indian American Friendship Council, accessed 06 June 2019, https://iafc.us/caucus.php

[10] Ashok Sharma, “The Indian-American lobby that’s quietly pushing Washington towards New Delhi,” Quartz India, 28 June 2017, accessed 02 June 2019, https://qz.com/india/1016611/the-indian-american-lobby-thats-quietly-pushing-washington-towards-new-delhi/

[11] US Congress, “H.Res.227 – Recognizing and honoring the contributions of Indian Americans to economic innovation and society generally.,” The 109th US Congress, 21 April 2005, accessed 13 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-resolution/227?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22india%22%5D%7D&s=4&r=549

[12] US Congress, “H.Con.Res.264 – Expressing the sense of Congress to welcome the Prime Minister of India, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, on the occasion of his visit to the United States, and to affirm that India is a valued friend and partner and an important ally in the campaign against international terrorism.,” The 107th US Congress, 07 November 2001, accessed 11 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/107th-congress/house-concurrent-resolution/264/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22india%22%5D%7D&r=663&s=5

[13] US Congress, “H.Res.562 – Expressing the sense of the House of Representatives that a postage stamp should be issued in commemoration of Diwali, a festival celebrated by people of Indian origin.,” The 107th US Congress, 26 September 2002, accessed 09 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/107th-congress/house-resolution/562?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22diwali%22%5D%7D&s=3&r=1

[14] Mark R. Warner, “Senate India Caucus,” Mark R. Warner – US Senator from the Commonwealth of Virginia, accessed 29 May 2019, https://www.warner.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/senate-india-caucus

[15] Jaswant Singh, “Against Nuclear Apartheid,” Foreign Affairs, 01 September 1998, accessed 01 June 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/asia/1998-09-01/against-nuclear-apartheid

[16] US Congress, “S.1886 – Naval Vessels Transfer Act of 2005,” The 109th US Congress, 18 October 2005, accessed 04 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/senate-bill/1886?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22india%22%5D%7D&r=524&s=3

[17] Ronen Sen, “INS Jalashwa a reflection of India-US trust,” Rediff News, 25 June 2007, accessed 07 June 2019, https://www.rediff.com/news/2007/jun/25guest.htm

[18] US Congress, “H.R.5682 – Henry J. Hyde United States and India Nuclear Cooperation Promotion Act of 2006,” The 109th US Congress, 26 June 2006, accessed 09 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/5682?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22india%22%5D%7D&r=476&s=2

[19] US Congress, “H.R.7081 – United States-India Nuclear Cooperation Approval and Nonproliferation Enhancement Act,” The 110th US Congress, 25 September 2008, accessed 04 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/house-bill/7081?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22india%22%5D%7D&r=375&s=3

[20] US Congress, “S.3847 – Security Cooperation Act of 2010,” The 111th US Congress, 27 September 2010, accessed 11 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/senate-bill/3847?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22india%22%5D%7D&r=289&s=2

[21] US Congress, “H.R.4825 – U.S.-India Defense Technology and Partnership Act,” The 114th US Congress, 22 March 2016, accessed 11 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/4825?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22H.R.4825+-+U.S.-India+Defense+Technology+and+Partnership+Act%22%5D%7D&s=7&r=2

[22] US Congress, “H.R.5387 – Special Global Partnership with India Act of 2016,” The 114th US Congress, 07 June 2016, accessed 18 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/5387?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22india%22%5D%7D&r=102&s=1

[23] US Congress, “H.R.5515 – John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019,” The 115th US Congress, 13 April 2018, accessed 05 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/5515/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22india%22%5D%7D&r=39&s=3#toc-HBC9EB1CFA1724C8AAF703D7EDADC8168

[24] US Congress, “H.R.2123 – United States-India Enhanced Cooperation Act of 2019,” The 116th US Congress, 08 April 2019, accessed May 22 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/2123?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22H.R.2123+-+United+States-India+Enhanced+Cooperation+Act+of+2019%22%5D%7D&s=5&r=1

[25] Walter Russel Mead, Special Providence – American Foreign Policy and How it Changed

the World, 2002, New York: Routledge, pg. 26

[26] Franklin D Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat – December 29, 1940,” The American Presidency Project – UC Santa Barbara, accessed 05 June 2019, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/fireside-chat-9

[27] George W Bush, “Bush State of the Union address,” CNN, 29 January 2002, accessed 10 June 2019, http://edition.cnn.com/2002/ALLPOLITICS/01/29/bush.speech.txt/

[28] Arthur Vandenberg, “Arthur Vandenberg: A Featured Biography,” The US Senate, accessed 22 May 2019, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/Featured_Bio_Vandenberg.htm

[29] Donald J Trump, “Europe has to pay their fair share for Military Protection. The European Union, for many years, has taken advantage of us on Trade, and then they don’t live up to their Military commitment through NATO. Things must change fast!,” Donald J Trump – Twitter, 26 November 2018, accessed 11 June 2019, https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1066790517944606721?s=20

[30] Bernie Sanders, “Sanders Introduces Bill to Rebuild America’s Crumbling Infrastructure, Support 13 Million Jobs,” Bernie Sanders – US Senator from Vermont, 27 January 2015, accessed 21 May 2019, https://www.sanders.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/sanders-introduces-bill-to-rebuild-americas-crumbling-infrastructure-support-13-million-jobs

[31] Jonathan Broder, “How Ilhan Omar Is Changing the Conversation About Israel—and Upending the 2020 Campaign,” The Newsweek, 19 April 2019, accessed 18 June 2019, https://www.newsweek.com/2019/04/19/ilhan-omar-democrats-israel-trump-1389677.html

[32] Sarah Posner, “Right Makes Might,” New Republic, 25 March 2019, accessed 07 June 2019, https://newrepublic.com/article/153276/republicans-congress-courted-nativist-authoritarian-leaders

[33] Kashish Parpiani, “ORF Issue Brief no: 281 — Institutionalising India-US defence ties in American legislative precedents,” The Observer Research Foundation, 26 February 2019, accessed June 01 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/research/institutionalising-india-us-defence-ties-in-american-legislative-precedents-48539/

[34] Pew, “Partisan Divides in Views of Many Countries – but Not North Korea,” Pew Research Center, 10 September 2018, accessed 27 May 2019, https://www.people-press.org/2018/09/10/partisan-divides-in-views-of-many-countries-but-not-north-korea/

[35] Alyssa Ayres, “How Americans see India as a power,” Forbes, 16 September 2015, accessed 05 November 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/alyssaayres/2015/09/16/how-americans-see-india-as-a-power/#3dc9bd41313d

[36] PTI report, “US wants fair, reciprocal trade with other countries: Trump,” Money Control, 27 October 2018, accessed June 20 2019, https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/world/us-wants-fair-reciprocal-trade-with-other-countries-trump-3094001.html

[37] David Lawder, “Democrat-led House seen backing Trump’s China trade war, scrutinizing talks with allies,” Reuters, 08 November 2018, accessed 16 June 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-elections-trade/democrat-led-house-seen-backing-trumps-china-trade-war-scrutinizing-talks-with-allies-idUSKCN1ND1HU

[38] DoD, “Indo-Pacific Strategy Report — Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting a Networked Region,” The US Department of Defense, 01 June 2019, accessed 01 June 2019, https://media.defense.gov/2019/May/31/2002139210/-1/-1/1/DOD_INDO_PACIFIC_STRATEGY_REPORT_JUNE_2019.PDF

[39] Pew, “Indian population in the U.S., 2000-2015,” Pew Research Center, 08 September 2017, accessed 13 June 2019, https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/chart/indian-population-in-the-u-s/

[40] ICWA, “Factoring Indian Diaspora in the Indo – U.S. Relationship”, Indian Council of World Affairs, 26 October 2018, accessed 13 June 2019, https://icwa.in/pdfs/IB/2014/IndianDiasporaVP26102018.pdf

[41] Prashant K Nanda, “ Flow of Indian students to US slows to a five-year low,” Live Mint, 14 November 2018, accessed 07 June 2019, https://www.livemint.com/Politics/XIMkOAAr2TcehexfAHj5DJ/Number-of-Indians-studying-in-US-up-by-54-since-last-year.html

[42] PTI report, “Indian-American lawmaker joins key Congressional committees,” The Times of India, 25 January 2019, accessed 02 June 2019, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/nri/us-canada-news/indian-american-lawmaker-joins-key-congressional-committees/articleshow/67685944.cms

[43] Pramila Jayapal, “Congressional Progressive Caucus Elects Leadership for the 116th Congress,” Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal for WA-07, 29 November 2018, accessed 15 June 2019, https://jayapal.house.gov/2018/11/29/congressional-progressive-caucus-elects-leadership-116th-congress/

[44] Akshobh Giridharadas, “Houston, we don’t have a problem: The bipartisan era of Indo-US diplomatic ties,” Observer Research Foundation, 23 September 2019, accessed 05 November 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/houston-we-dont-have-a-problem-the-bipartisan-era-of-indo-us-diplomatic-ties-55742/

[45] Anil Sasi, “Explained: Issues in India-US trade,” The Indian Express, 09 May 2019, accessed 23 May 2019, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/donald-trump-wilbur-ross-commerce-industry-india-us-trade-suresh-prabhu-5717901/

[46] PTI report, “US lawmaker urges USTR to delay GSP decision till Indian elections,” The Economic Times, 30 March 2019, accessed 23 May 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/us-lawmaker-urges-ustr-to-delay-gsp-decision-till-indian-elections/articleshow/68642969.cms?from=mdr

[47] PTI report, “Senators urge Trump govt to delay decision on India’s GSP review to after polls,” India Today, 13 April 2019, accessed 23 May 2019, https://www.indiatoday.in/business/story/senators-urge-trump-administration-to-delay-decision-on-india-s-gsp-review-1500939-2019-04-13

[48] PTI report, “Senators urge Trump govt to delay decision on India’s GSP review to after polls,” India Today, 13 April 2019, accessed 23 May 2019, https://www.indiatoday.in/business/story/senators-urge-trump-administration-to-delay-decision-on-india-s-gsp-review-1500939-2019-04-13

[49] PTI report, “Suspension of preferential trade status for India under GSP is ‘done deal’: Trump,” Business Today, 31 May 2019, accessed 31 May 2019, https://www.businesstoday.in/current/economy-politics/suspension-of-preferential-trade-status-for-india-under-gsp-is-done-deal-trump/story/352427.html

[50] PTI report, “GSP countries like India to benefit from US trade war with China: Report,” The Economic Times, 15 May 2019, accessed 01 June 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/gsp-countries-like-india-to-benefit-from-us-trade-war-with-china-report/articleshow/69343500.cms

[51] PTI report, “GSP countries like India to benefit from US trade war with China: Report,” The Economic Times, 15 May 2019, accessed 01 June 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/gsp-countries-like-india-to-benefit-from-us-trade-war-with-china-report/articleshow/69343500.cms

[52] PTI report, “GSP countries like India to benefit from US trade war with China: Report,” The Economic Times, 15 May 2019, accessed 01 June 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/gsp-countries-like-india-to-benefit-from-us-trade-war-with-china-report/articleshow/69343500.cms

[53] PTI report, “Senators urge Trump govt to delay decision on India’s GSP review to after polls,” India Today, 13 April 2019, accessed 23 May 2019, https://www.indiatoday.in/business/story/senators-urge-trump-administration-to-delay-decision-on-india-s-gsp-review-1500939-2019-04-13

[54] Neha Dasgupta and Aditya Kalra, “US Tells India it May Cap H-1B Visas to Counter Data Localisation Plans,” The Print, 20 June 2019, accessed 05 November 2019, https://thewire.in/diplomacy/us-india-h1b-visa-data-localisation

[55] Shashidhar K J and Kashish Parpiani, “Easing the US-India divergence on data localisation,” Observer Research Foundation, 22 July 2019, accessed 05 November 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/easing-us-india-divergence-data-localisation-53256/

[56] Lubna Kably, “H-1B cap for India? It’s not easy and may need approval by US Congress, say experts,” The Times of India, 20 June 2019, accessed 20 June 2019, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/h-1b-cap-for-india-its-not-easy-and-may-need-approval-by-us-parliament-say-experts/articleshow/69868230.cms

[57] HFAC, “Membership – House Foreign Affairs Committee,” The US House of Representatives – The 116th Congress, accessed 10 May 2019, https://foreignaffairs.house.gov/members

[58] HFAC, “Membership – Asia, the Pacific, and Nonproliferation – House Foreign Affairs Committee,” The US House of Representatives – The 116th Congress, accessed 10 May 2019, https://foreignaffairs.house.gov/asia-the-pacific-and-nonproliferation

[59] IAFC, “Congressional Caucus on India and Indian Americans,” The Indian American Friendship Council, accessed 10 May 2019, https://iafc.us/caucus.php

[60] Brad Sherman, “Sherman Meets with Ambassador S. Jaishankar of India,” Congressman Brad Sherman, 16 January 2014, accessed 10 May 2019, https://sherman.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/sherman-meets-with-ambassador-s-jaishankar-of-india

[61] IAFC, “Congressional Caucus on India and Indian Americans,” The Indian American Friendship Council, accessed 10 May 2019, https://iafc.us/caucus.php

[62] Albio Sires, “Committees and Caucuses,” Congressman Albio Sires, accessed 10 May 2019, https://sires.house.gov/about/committees-and-caucuses

[63] Joe Wilson, “Caucuses,” Congressman Joe Wilson, accessed 10 May 2019, https://joewilson.house.gov/about/caucuses

[64] Ami Bera, “Indian American Rep. Ami Bera to Co-Chair House India Caucus,” Congressman Ami Bera, accessed 10 May 2019, https://bera.house.gov/media-center/in-the-news/indian-american-rep-ami-bera-to-co-chair-house-india-caucus

[65] Joaquin Castro, “Committees and Caucuses,” Congressman Joaquin Castro, accessed 10 May 2019, https://castro.house.gov/legislation/committees-and-caucuses

[66] Brian Fitzpatrick, “Committees & Caucuses,” Congressman Brian Fitzpatrick, accessed 10 May 2019, https://fitzpatrick.house.gov/committees-and-caucuses

[67] Ted Lieu, “Committees & Caucuses,” Congressman Ted Lieu, accessed 10 May 2019, https://lieu.house.gov/about/committees-and-caucuses

[68] Jim Costa, “Costa Hosts Ambassador Rao of India in Fresno,” Congressman Jim Costa, 02 September 2013, accessed 10 May 2019, https://costa.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/costa-hosts-ambassador-rao-india-fresno

[69] SFRC, “Membership – Senate Foreign Relations Committee,” The US Senate – The 116th Congress, accessed 22 May 2019, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/about/membership

[70] SFRC, “Membership – Subcommittee On Near East, South Asia, Central Asia, And Counterterrorism – Senate Foreign Relations Committee,” The US Senate – The 116th Congress, accessed 22 May 2019, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/about/subcommittees/

[71] Mark R. Warner, “Senate India Caucus,” Mark R. Warner – US Senator from the Commonwealth of Virginia, accessed 22 May 2019, https://www.warner.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/senate-india-caucus

[72] Mark R. Warner, “Senate India Caucus,” Mark R. Warner – US Senator from the Commonwealth of Virginia, accessed 22 May 2019, https://www.warner.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/senate-india-caucus

[73] Mark R. Warner, “Senate India Caucus,” Mark R. Warner – US Senator from the Commonwealth of Virginia, accessed 22 May 2019, https://www.warner.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/senate-india-caucus

[74] Chris Coons, “Senator Coons’ Caucus Memberships,” Senator Chris Coons, accessed 22 May 2019, https://www.coons.senate.gov/about/caucuses

[75] However, Sen. Romney’s predecessor from Utah, senior Sen. Orrin G. Hatch was a prominent member of the Senate India Caucus

[76] Mark R. Warner, “Senate India Caucus,” Mark R. Warner – US Senator from the Commonwealth of Virginia, accessed 22 May 2019, https://www.warner.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/senate-india-caucus

[77] Mark R. Warner, “Senate India Caucus,” Mark R. Warner – US Senator from the Commonwealth of Virginia, accessed 22 May 2019, https://www.warner.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/senate-india-caucus

[78] Tim Kaine, “Warner, Cornyn, Kaine, And Risch Introduce Senate Resolution Highlighting Importance Of U.S.-India Strategic Partnership,” Senator Tim Kaine, 30 July 2014, accessed 22 May 2019, https://www.kaine.senate.gov/press-releases/warner-cornyn-kaine-and-risch-introduce-senate-resolution-highlighting-importance-of-us-india-strategic-partnership

[79] Mark R. Warner, “Senate India Caucus,” Mark R. Warner – US Senator from the Commonwealth of Virginia, accessed 22 May 2019, https://www.warner.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/senate-india-caucus

[80] PTI report, “Senator Cory Anthony Booker joins Senate India Caucus,” The Economic Times, 14 August 2014, accessed 22 May 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/senator-cory-anthony-booker-joins-senate-india-caucus/articleshow/40245717.cms

[81] Andrew Desiderio, “The House committee quietly racking up oversight wins against Trump,” Politico, 17 June 2019, accessed 17 June 2019, https://www.politico.com/story/2019/06/17/house-foreign-affairs-panel-oversight-trump-1365840

[82] State Dept. “U.S. Security Cooperation With India – Factsheet,” The US State Department, 04 June 2019, accessed 04 June 2019, https://www.state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-india/

[83] WaPo, “Tracking how many key positions Trump has filled so far,” The Washington Post, 17 June 2019, accessed 17 June 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/politics/trump-administration-appointee-tracker/database/?utm_term=.2b213b8bb753

[84] US Senate, “The Amending Process in the Senate,” The US Senate – The 116th Congress, 16 September 2015, accessed 19 June 2019, https://www.senate.gov/CRSpubs/738b4c8d-66ee-4c11-9b6a-176194c4456a.pdf

[85] Samir Saran, “India-US relationship: Is the top-down structure sustainable?”, Observer Research Foundation, 06 July 2018, accessed 25 November 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/research/42262-india-us-relationship-top-down-structure-sustainable/

[86] US Congress, “H.R.3730 – United States-India Interparliamentary Exchange Act of 2007,” The 110th US Congress, 02 October 2010, accessed 18 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/house-bill/3730?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22India+Interparliamentary%22%5D%7D&s=1&r=9

[87] US Congress, “H.R.2468 – United States-India Interparliamentary Exchange Act of 2009,” The 111th US Congress, 18 May 2009, accessed 18 June 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/2468?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22India+Interparliamentary%22%5D%7D&s=1&r=8

[88] Kashish Parpiani, “US Congress hearing on Kashmir: India falls prey to American political polarisation”, Observer Research Foundation, 25 October 2019, accessed 25 November 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/us-congress-hearing-on-kashmir-india-falls-prey-to-american-political-polarisation-57073/

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Kashish Parpiani is Senior Manager (Chairman’s Office), Reliance Industries Limited (RIL). He is a former Fellow, ORF, Mumbai. ...

Read More +