Introduction

China has experienced unprecedented growth since the 1990s. Massive infrastructure development broadened its industrial base, and rural expansion and widespread advancement propelled the country to a dominant position in the new world order. Over the years, China has registered an excess production of iron, steel, cement, aluminium and other building materials,[1] which it turned “into an opportunity by ‘moving out’ this overcapacity based on its development strategy abroad and foreign policy”.[2] President Xi Jinping’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) provided an opportunity to convert this domestic overcapacity into a strategic advantage by aggressively pursuing the country’s geostrategic, geopolitical and geoeconomic ambitions. The Xinjiang province became a natural and critical hub in the initiative due to its geostrategic location as China’s gateway to Eurasia and an area with abundant natural resources. Three of the BRI’s six megaprojects run through Xinjiang, including the controversial and sensitive China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Given its contested history and centrifugal tendencies, securing Xinjiang has become a precondition for China to protect this “project of the century”.[3]

In a bid to consolidate its influence and power in Xinjiang, given the Uyghur Muslims’ contested histories based on culture, separatism and occasional violent extremism, Beijing began a ‘cultural aggression’ towards the Uyghurs through the 2014 ‘Strike Hard Campaign’.[4] Under this campaign, Xi advocated using the “weapons of the people’s democratic dictatorship” without “any hesitation or wavering’” and to disregard rights violations against Muslims in the province.[5] An estimated one million Muslims were sent to detention camps for forced re-education and political indoctrination.[6] In 2017, following the BRI’s inclusion in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) constitution, Xi called for the building of a “great wall of iron”[7] to protect China’s national unity and solidarity in the troubled Xinjiang province. This announcement prompted Beijing to escalate its authoritarianism, consolidate its territorial control, and minimise security threats in Xinjiang.

Beijing also used the BRI to ‘replicate’ its Xinjiang model of demographic changes, socioeconomic exploitation of indigenous resources, and surveillance methods in Pakistan and Central Asia to varying degrees.[8]

At the same time, Western democracies took an uncompromising stand on China’s actions against its Uyghur Muslim minorities. In the final year of Donald Trump’s presidency, the US enacted a series of measures, including the imposition of broad and targeted economic sanctions against senior CCP officials, banning imports from Xinjiang that were the products of forced labour, and declaring the CCP’s repressive policies against Uyghurs as “genocide”.[9] However, all major Muslim countries[a] remained silent on the issue, and some even endorsed Beijing’s actions.[10] Many Muslim countries also detained Uyghur exiles and repatriated them to China.[11]

Looking beyond Beijing’s mercantilist ideology, the paper attempts to highlight the causes of the silence from the Muslim world on the Uyghur issue. These include the authoritative regimes in many Muslim countries, their human rights records,[12] China’s non-intervention policy, and Beijing’s perception management through the Chinese Islamic Association. This paper also analyses the CCP’s diplomatic strategies in various Muslim countries. Crucially, it seeks to evaluate the ramifications of the Muslim world’s silence due to Beijing’s strategic heft on the western democratic world.

CCP and Uyghur Muslims: A Brief History

Xinjiang has experienced intermittent phases of autonomy and occasional independence, with the Chinese imperial powers having complete control for only about 425 years.[13] Xinjiang was incorporated as a new province of the Chinese Empire in 1878 after the Qing rulers conquered it in the eighteenth century. At the time of the 1949 Revolution, Xinjiang was independently ruled under the East Turkestan Republic, with a contested history and centrifugal tendencies.[b]

After getting firm control over Xinjiang, the CCP announced a new policy to culturally homogenise the region by introducing the communist doctrine of ‘togetherness’ of all societies into a ‘whole unit’ across China. The minority populations of Tibet and Xinjiang became the primary target for social cohesion and Sinicisation. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), CCP cadres attacked the customs, ideas and habits of Xinjiang natives, especially those who showed centrifugal tendencies and belonged to a different culture. Mao Zedong’s wife Jiang Qing considered these people as “foreign invaders and aliens”.[14] By 1966, authorities were urged to close mosques, disperse religious associations, abolish Quranic studies, and ban interfaith marriages and circumcisions.[15] Before 1949, Xinjiang had 29,545 mosques; following the Cultural Revolution, only 1400 remain functional.[16]

Subsequently, Beijing moved millions of Han people to the strategic and resource-rich parts of the province. The primary objective of pushing Han migrants into Xinjiang was to ensure the “subjugation of the national minorities”[17] and secure the province from international influences, particularly the former Soviet Union. The Han and CCP members replaced Non-Han families living along the border to curtail Soviet influence.[18] After 1949, widespread Han migration reduced the Uyghurs to a negligible minority in most new cities developed in northern Xinjiang, such as the capital Ürümqi (73 percent Han), Karamai (75 percent Han) and Shihezi (94 percent Han).[19] The Han migration also led to a demographic change in Xinjiang—between 1941 and 1980, the Han population grew from 5 percent to 40 percent while the Uyghur population fell from 80 percent to 45.8 percent.[20]

1978 Economic Reforms and Separatism in Xinjiang

Following Mao’s death, China reviewed its socioeconomic policies at the 3rd Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee held in Beijing in 1978, marking the early signs of the country’s acceptance of liberalisation and a change in the CCP’s attitude towards Xinjiang’s Uyghur Muslims. Article 36 of the 1982 constitution allowed the state to protect “normal religious activities,”[21] giving the Uyghurs freedom in cultural matters but only under the strict supervision of CCP authorities. Muslims were allowed to travel to Islamic countries and contact with Muslims abroad was encouraged.[22]

Around the same time, China’s relationship with Pakistan strengthened with the completion of the Karakoram highway that connects Xinjiang with Gilgit-Baltistan (construction began in 1959 and was completed in 1979, and the highway opened for public use in 1986).[23] This opened up China’s southern regions to Pakistan’s religious and cultural influences and other Muslim countries. Radical religious literature became available, and Muslim religious preachers (mullahs) from Pakistan started educating the Uyghurs in the newly created madrassas.[24] The Soviet occupation of Afghanistan allowed the mullahs to interpret jihad to enthuse the people. As a result, some Uyghurs joined the mujahedeen in Afghanistan to fight on behalf of the Northern Alliance or the Taliban.[25]

At the same time, Uyghur Muslims held anti-China agitations in 1980, 1981, 1985 and 1987, culminating in the Baren incident in 1990 when a group of Uyghurs criticised local government policies and started a mass protest to wage jihad against the Chinese to establish an East Turkestan state.[26] According to Chinese government sources, six police officers and 15 demonstrators were killed in the protest. Chinese officials claim that mujahedeen units in Afghanistan trained the Uyghur agitators. Subsequently, the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM, later known as Turkistan Islamic Party) was founded as a separatist group by the Turkic-speaking ethnic majority in Xinjiang.[27]

To suppress the separatists in Xinjiang, Beijing started the ‘Strike Hard’ campaign in 1996, targeting “splittism and illegal religious activities”.[28] CCP groups monitored the religious activities, and mullahs appointed by the government to lead prayers in the mosques were asked to write loyalty letters to the CCP government in Xinjiang. Maintaining social stability in Xinjiang became China’s top priority. Most madrasas that started after 1978 were closed, and more than 2,700 alleged terrorists and other criminals were captured by 1996.[29]

However, the ‘Strike Hard’ campaign proved counterproductive. In February 1997, hundreds of Uyghurs protested at Yining near the Kazakhstan border for Xinjiang’s independence. The incident is the largest publicly known anti-Beijing separatist protest in the region, with government forces killing more than ten people and injuring hundreds. In Aksu, another hotbed of protests, the separatists kidnapped several police officers, who were freed following a raid and the killing of the separatists.[30]

In the aftermath of the September 2001 attacks on the US, China also used the global war on terror to suppress the Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, using instances of violent attacks by ETIM as justification.[31]

Great Western Development Project and Heightened Ethnic Tensions

Wary of separatist rumblings in Xinjiang, Beijing embarked on an ambitious ‘development campaign’ (the Great Western Development Project) in the region in 2000. The CCP believed that the growing economic disparity between Xinjiang and the mainland was a primary reason for increased anti-China sentiment and that separatist tendencies will diminish if the Uyghurs could be lured with financial prosperity. The strategy aimed to integrate and assimilate the restive Uyghur population with mainland China.[32] It envisaged developing infrastructure, railway tracks, airports, oil and gas pipelines, power grids, industries, and telecommunications networks, and measures to attract foreign investment for capital, technology and managerial expertise by improving the industrial structure. Xinjiang received RMB 1.4 trillion (US$215 billion) between 2000 and 2009, 80 percent of which came from the central government.[33]

The Western Development Project created a new platform to attract more Han migrants. It soon became clear that the programme was only meant to increase the Han population and did not benefit Uyghurs.[34] A 2010 population survey revealed that two-and-a-half times more Uyghurs worked in the primary sector (agriculture) than Han. On the other hand, the Han workforce in the secondary and tertiary sectors outmatched the Uyghurs by more than six times. The Han dominance in every social sphere fanned further ethnic discord with the indigenous Uyghurs.[35]

These tensions culminated in ethnic riots in July 2009 in Ürümqi. The immediate cause of the riots was a brawl between the Uyghur and Han workers in Guangdong province on 25 June, in which two Uyghur people were killed and 118 were injured.[36] On 5 July 2009, a protest march by thousands of Uyghurs to demand an investigation into the riots turned violent. Two days later, the Han attacked the Uyghurs in Ürümqi with knives, hammers, and wooden clubs. According to official records, 200 people lost their lives, and more than 1,600 were injured.[37] However, the Uyghurs claim that over 800 people were killed by the Chinese security forces and the Han.[38] More than 4,000 Uyghurs were detained.[39] As the crackdown on the Uyghurs intensified, and prisons in Ürümqi were filled beyond capacity, ad hoc detention facilities, including army warehouses, were used as detention centres.

A Hardened Approach

After the commencement of the BRI, Xinjiang’s security, social cohesion and Sinicisation gained greater significance for the CCP. Tactics deployed by China before 2013 (before the BRI) to curb centrifugal tendencies in the restive Xinjiang failed to yield any result. Beijing attempted to reorient Xinjiang ‘inward’ under mainland China’s cultural influence through policies and initiatives like the Western Development Project. However, Xinjiang’s “geographic template” produced axes of outside cultural influence that penetrated the region and determined that Xinjiang remained oriented “outward”.[40] For example, the Uyghur used CCP infrastructure projects to change their oasis identities (such as Kashgari, Khotani and Yarkandi) to an ethnic ‘Uyghur identity’ and eventually a global ‘Muslim identity’. In June 2013, the Uyghurs attacked a police station and government offices, with 27 killed in retaliatory police firing.[41] China’s approach toward the Uyghur population hardened following the March 2014 mass knife attack at Kunming railway station that left 31 people dead and nearly 150 injured.[42]

Under the new hardened approach, Chen Quanguo, a soldier-turned-politician known for his anti-minorities policies in Tibet, was sent to Xinjiang as the CCP’s secretary for the province in 2016. Chen rolled out his securitisation strategy within a year and made Xinjiang the most high-tech surveillance zone in China. Beijing has spent US$700 million since 2017 to construct 1,200 detention camps across Xinjiang.[43] Muslims are sent to detention centres for “offences,” including “wearing a veil,” growing “a long beard,” and violating the government’s family planning policy. Beijing has also resorted to DNA profiling, blood sampling, fingerprinting and voice sampling and has increased vigilance through technical intelligence analysis.[44]

Uyghur women are subjected to forced sterilisations, abortions and the implantation of contraceptive devices through state-sponsored campaigns.[45] Xinjiang accounts for just 1.8 percent of the Chinese population, but 80 percent of intrauterine devices used in 2018 were implanted in Uyghur women.[46] As a result, between 2015 and 2018, the natural population growth rate fell by 84 percent, from 1.6 percent to 0.26 percent, in Khotan and Kashgar cities in southern Xinjiang. The suppression of population growth among Muslims has been so severe that the 2020 Xinjiang yearbook did not present the region’s official population data for the first time ever.[47] Furthermore, women detainees are starved and delivered only 200 gm of drinking water per day. Some are paraded in front of male police officers with shaved heads.[48]

Mass rapes,[49] torture through waterboarding and illegal organ harvesting are thought to be rampant in the detention camps,[50] and detainees are also used for forced labour. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the local administration sent detainees to work at manufacturing units in other parts of the country,[51] and reports suggested that the CCP resorted to a “kill-on-demand”[52] strategy as an emergency measure to harvest the organs of the Uyghur detainees to cater to the increased organ demand in the mainland.

Uyghur Muslims working in government departments, especially teachers, are forced to pledge “that neither they nor their family will perform namaz (five prayers a day), wear a headscarf or wear religious clothing,” and will educate the guardians of their students to refrain from offering the namaz and participating in other religious activities.[53] Since 2017, performing namaz (prayers) is considered an “illegal religious activity,” and Uyghurs are fined for performing this essential religious duty.[54]

Uyghur Issue: Reactions from the Muslim World

In 2018, the Chinese foreign ministry denied the existence of re-education camps, saying it “had not heard of this situation”.[55] However, when news of atrocities on Uyghurs began to appear in the western media, Chinese officials (including CCP’s Xinjiang chairman Shohrat Zakir) defended the detention centres as a means to combat extremism, separatism, and terrorism. They claim the detention camps have helped wean out extremist and radical thoughts and presented Uyghur youth with better economic opportunities.[56] The centres are vocational school-style spaces where skill development training is provided with free meals and accommodation.[57] Chinese officials publicly maintain that the camps have two purposes—to teach Mandarin, Chinese laws and vocational skills; and to prevent citizens from becoming influenced by extremist ideas (claiming to set them free after graduation).[58]

Western democracies have repeatedly voiced concerns at regional and global platforms, criticising the CCP and banning the import of goods made through forced labour. Canada, the US and Lithuania have termed China’s actions in Xinjiang as genocide,[59] and the US and the European Union have imposed sanctions on the country. The US has banned “exports to China that its authoritarian government can use in its repression of the Uyghurs.”[60] But Beijing has dismissed the western criticism as misinformation or as conspiracy and has said the US ban on cotton imports from China “was built on fabrications, not on facts.”[61]

At the same time, authoritative Muslim countries, including Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Pakistan, Turkey, Malaysia, and Iran and the Central Asian republics, have toed Beijing’s official line. In 2019, 22 western countries, including Japan and the UK, wrote a joint letter to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to act against China’s repressive policies in Xinjiang.[62] The following day, 37 countries, mainly Muslim nations (including Pakistan, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman, Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan), issued a joint letter commending China’s efforts in “protecting human and promoting human rights through development”.[63] The envoys of these countries wrote, “the past three consecutive years have seen not a single terrorist attack in Xinjiang and people there enjoy a stronger sense of happiness, fulfilment and security”.[64]

Since 2014, rulers of Muslim countries have either remained silent or endorsed the Chinese policies in Xinjiang. During his 2019 visit to Beijing, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan used a soft line on the detention camps and cautioned that the issue was being “exploited”.[65] Similarly, during his 2019 visit to China, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman endorsed the CCP’s Uyghur policies and said Beijing has right to “carry out anti-terrorism and de-extremization work for its national security.”[66] Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan, who has positioned himself as a defender of the Islamic world, said China’s take on the Uyghur issue was completely different from what is reported in the Western media. “Because of our extreme proximity and relationship with China, we actually accept the Chinese version,” he said.[67]

China’s repressive policies and dominance of its Uyghur population are not limited to Xinjiang alone. Beijing has abused its economic clout, strategic heft and diplomacy to force major Muslim countries to sign extradition treaties and deport Uyghurs in those countries. Turkey, the Muslim country with the largest Uyghur diaspora, has also been diplomatically pressurised to sign an extradition treaty that has still not been ratified by its parliament.[68] Since 2017, 682 Uyghurs have been detained in Egypt, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Qatar, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, the UAE, and Uzbekistan,[69] and some Muslim countries have detained Uyghur exiles even without rectifying extradition treaties (see Table 1).

Table 1: Muslim Countries that have Detained or Extradited Uyghurs

| Country |

Extradition treaty with China |

Uyghurs detained or extradited to China |

Signatory to 2019 letter to UN |

| Kazakhstan |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Kyrgyzstan |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Uzbekistan |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Pakistan |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Iran |

Yes |

No data |

Yes |

| UAE |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Tajikistan |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Turkey |

Not ratified by Turkish parliament |

Yes |

No |

| Saudi Arabia |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

| Malaysia |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Afghanistan |

No |

Yes |

|

| Egypt |

No |

Yes |

|

| Qatar |

|

Yes |

Yes |

Source: Compiled by author

The reluctance of Muslim countries to speak up about China’s actions in Xinjiang can be ascribed to the following reasons:

Muslim Authoritative Regimes and Insecurity

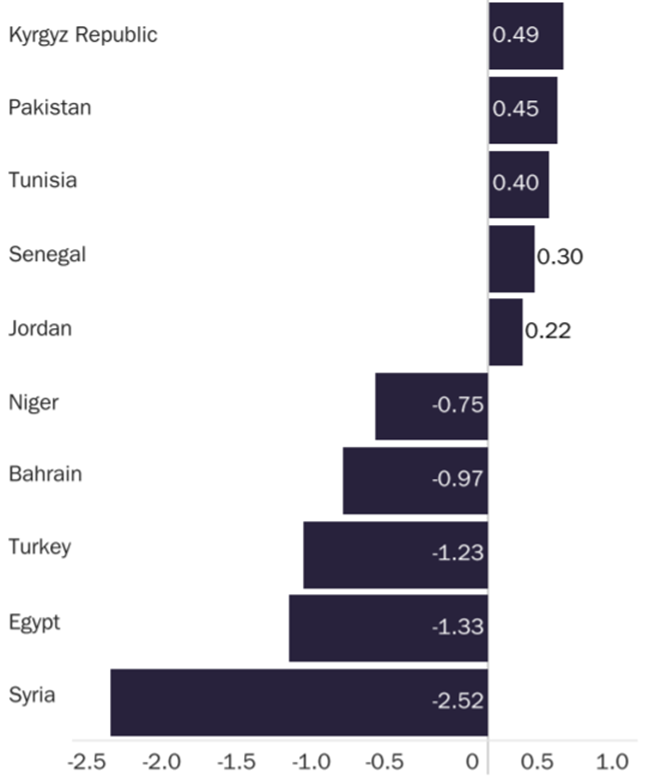

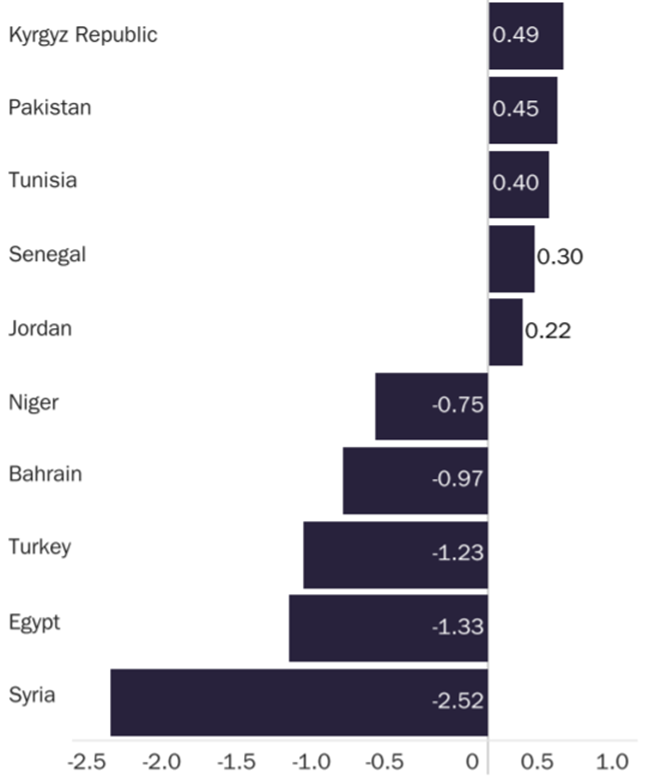

According to the 2020 Democracy Index, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are among the 21 most authoritarian regimes globally.[70] At the same time, according to the 2019 Human Freedom Index, Turkey, Egypt and Bahrain have shown dramatic deteriorations in personal freedoms.[71]

Figure 1: Personal Freedoms in Muslim Countries (Most Improved and Most Deteriorated, 2008-2017)

Source: ‘Freedom in the Muslim World’[72]

The Muslim world has a poor human-rights record, and even some of the most influential member-countries of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) have a history of ill-treating their minority populations. For example, according to a 2018 rights report by the US State Department, Saudi Arabia is guilty of unlawful killings, arbitrary arrests, forced detentions and disappearances, and the torture of prisoners and detainees by government agents.[73] Similarly, Pakistan has been accused of muzzling dissenting voices in nongovernmental organisations and the media and quashing the Baloch separatist movement using similar tactics to China’s Xinjiang strategy. According to a report by the Human Rights Council of Balochistan, over 47,000 Baloch are reported missing, and in 2019 alone, 241 were killed, 568 disappeared and numerous protesting students were targeted.[74]

In the aftermath of the 2016 attempted coup in Turkey, Erdoğan ordered the arrest of over 7,500 persons, including 755 judges and prosecutors, while thousands of others, including police officers, were suspended. With Erdoğan assuming unchecked powers since 2016, Turkey has seen a human rights crisis and the erosion of the rule of law.[75]

Similarly, Iran has used excessive and lethal force and arbitrary arrests against peaceful assembly and expression.[76] In the UAE, allegations of torture in detention, arbitrary arrests and detentions are commonplace. Additionally, the Saudi-led collation in Yemen, of which the UAE is also a member, has been accused of killing many civilians, damaging infrastructure, and torturing, sexual assaulting and mistreating detainees.[77]

The history of human rights violations by authoritative regimes in the major Muslim countries has often spurred the US-led western democracies to pursue interventional policies. Rising Islamophobia in the aftermath of the September 2001 terror attacks in the US has only made the western liberal democracies circumspect of such authoritarian regimes. The intolerance of Islam in the US peaked during the Trump regime. Within weeks of assuming power, Trump banned citizens from seven predominantly Muslim countries from entering the US for 90 days and blocked Syrian refugees.[78] Trump’s unlimited support to Israel and for the intimidation and coercion of Palestine (by cutting down US$200 million in aid) also angered Muslim countries.[79] Furthermore, the Trump administration’s inward-looking policy, the alleged US-backed attempted coup in Turkey, and the withdrawal from the Iran Nuclear Deal increased the animosity between the West (particularly the US) and the Muslim world. The failure of the US-led coalition in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan only increased this mistrust.

Beijing has taken advantage of these prevailing conditions to further its parochial mercantilist ideology and hegemonic pursuits. Under the grab of the ‘five principles of peaceful coexistence’, the CCP developed a unique approach towards Muslim countries based on a non-interventionist policy focused on upholding territorial integrity and sovereignty, but that would fulfil its mercantilist and hegemonic ambitions. In stark contrast to the West’s interventionist approach, Beijing’s ties with Muslim nations are based on mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in the other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence.

Decoding China’s Strategies: BRI, Investments, Loans and Strategic Partnerships

Most Muslim countries have embraced the BRI, which projects Beijing’s global ambitions while addressing its domestic economic and political concerns. BRI participant countries, especially those with weak economies, have borrowed funds from Beijing for infrastructure projects, the work for which is often carried out by Chinese workers and firms that may otherwise be idle given the oversaturated domestic market.[80] About 89 percent of all BRI projects have gone to Chinese construction companies, 7.6 percent to locals, and 3.7 percent to other foreign companies.[81] According to the World Bank, completed BRI projects will boost trade, cut travel time in the economic corridors by 12 percent, lift 7.6 million people out of extreme poverty, and increase incomes by 3.4 percent. But it has also cautioned about impending debt risks, stranded infrastructure, environmental and social threats, and corruption associated with the BRI.[82]

Table 2: China’s Investments in Muslim Countries After BRI Inception and Signed Partnerships

| Country |

Chinese Investments after the launch of BRI until 2018 (in US$ billion) |

Comprehensive Strategic Partnership/Strategic Partnership (year of inception) |

| Saudi Arabia |

14.9 |

2016 |

| UAE |

21.9 |

2018 |

| Iran |

13.6 |

2016 |

| Egypt |

19.29 |

2014 |

| Algeria |

8.24 |

– |

| Pakistan |

62 under proposed CPEC |

– |

| Turkey |

3.6 |

2010 |

|

|

|

Source: Compiled by author

Pakistan and Turkey have also received substantial investments and loans from China. The US$62 billion CPEC is considered the crown jewel of the BRI. Turkey has received a US$3.6 billion loan from Beijing for investments in infrastructure and through credit swap lines to boost its foreign reserves.[83] In June 2021, Erdoğan announced a new deal between Beijing and Istanbul, increasing the existing currency swap limit to US$6 billion.[84]

China has signed comprehensive strategic partnerships and strategic partnerships with most leading Muslim countries in West Asia, using partnership diplomacy instead of alliances to further its interests. The comprehensive strategic partnerships compel both countries to a “full pursuit of cooperation and development on regional and international affairs,” while strategic partnerships require both countries to “coordinate more closely on regional and international affairs, including military”.[85] On the other hand, in an alliance, the strong side always “fears entrapment or getting entangled in the weaker side’s conflicts, while the weaker side fears abandonment”.[86] China’s strategic partnerships have kept it free of such responsibilities and allowed it to pursue its diplomatic non-intervention and maintain territorial integrity and sovereignty in West Asia.

Energy Diplomacy

China’s demand for energy rose significantly in the 1990s. Its daily oil consumption increased from 4.2 million barrels in 1998 to 13.5 million barrels in 2018. In 2019, Beijing surpassed the US to become the world’s largest oil importer, accounting for 16.7 percent of the global crude oil imports.[87] China’s energy demands, including oil imports, are expected to double and its use of natural gas is expected to increase by nearly 190 percent between 2018 and 2050.[88] In 2020, China spent US$176.2 billion on crude oil imports,[89] most of which was sourced from West Asia. Beijing has made long-term purchasing agreements with major energy exporters in the region. In 2019, China imported crude oil worth US$40.1 billion (16.8 percent of Beijing’s total crude imports) from Saudi Arabia, US$16.4 billion (6.9 percent) from Oman, US$7.3 billion (3.1 percent) from the UAE, US$7.1 billion (3 percent) from Iran, and US$5.5 billion (2.3 percent) from Malaysia.[90] China is the top crude oil export destination for Saudi Arabia, Iran, Kuwait, and Oman.

On the other hand, in 2014, the US’s oil imports fell to 260,000 barrels per day, the lowest in two decades. The US’s reduced reliance on oil imports came from its successful domestic hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling that unlocked vast reserves of tight oil from the shale rock formations.[91] In 2015, following the US’s oil exports to Europe, global crude prices fell below US$50 a barrel, hugely impacting the oil-rich Muslim countries.[92] In such a scenario, the lure of China’s energy market and potential long-term agreements were tempting enough for West Asian Muslim countries to maintain restraint on the Uyghur issue.

Perception Management Through Chinese Islamic Association

While the US and the western world were focused on targeting Muslims and the Islamic world in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks, Beijing used Islam as an effective foreign policy tool and a domestic security strategy. China eroded the Uyghur’s Islamic culture and carried out ethnic cleansing in Xinjiang, and banned namaz (prayers) within its borders.

On the other hand, the 2011 Arab uprisings saw a dramatic and direct outreach of political Islam between China, Russia and several Muslim countries in West Asia. The wave of political Islam and mass mobilisation that swept through the Muslim world since 2011 created an existential threat to the ruling authoritarian regimes in the region.[93] The West Asian governments dreaded the rise of radical Islamist tendencies, but the eruption of civil war became a cause of concern for the Saudi-UAE-Egypt axis of autocratic states. The ruling regimes feared the emergence of a democratic paradigm could undermine their authoritative status quo. Beijing and Russia deepened their religious engagement with the Saudi-UAE-Egypt axis to help these countries re-establish state-controlled religious discourse, much like they have developed in their own countries.[94] Additionally, the western media portrayed the Saudi-UAE-Egypt axis as a more substantial threat to global peace, stability and liberal values than the radical forces in the region. This strategy helped Moscow and Beijing break West Asia’s propensity towards American unipolarity and establish a greater sway over the region. In 2019, as China used the same rhetoric of political Islam to detain more than one million Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, the Saudi-UAE-Egypt combine and Qatar, and 33 other countries, sent a letter to the UN to defend China’s actions in Xinjiang. The letter stated that “terrorism, separatism and religious extremism have caused enormous damage to people of all ethnic groups in Xinjiang”.[95] The clever use of political Islam for this purpose dramatically increased Beijing’s heft over the Muslim authoritarian regimes through intense diplomatic, economic and military engagement.

Subsequently, Beijing controlled the narrative of Islam through the Chinese Islamic Association (CIA), an apex government body to look after Islamic discourse and religious activity. Since the launch of the BRI, Beijing has used the CIA to promote an Islamic soft power to build relations across the Muslim world. The CIA also oversees religious outreach with Muslim countries and arranges official exchanges with Muslim leaders and institutions. After the 2009 Ürümqi riots, the OIC sent an official fact-finding delegation to Beijing and Xinjiang headed by Ambassador Sayed Kassem al-Masry, an advisor to the OIC and Egypt’s former envoy to Saudi Arabia. Besides meeting state officials, the delegation also met Chen Guangyuan, the then-president of the CIA.[96] CIA officials kept a close watch on all the meetings. After the 2014 Kunming attacks, the CIA hosted an Islamic conference in Xinjiang that was attended by Islamic scholars from several Muslim countries and other global officials. In 2016, the CIA invited many religious groups from the OIC, Malaysia, Indonesia and Afghanistan to an international seminar in Ürümqi on Islamic ideals.[97] In 2019, the CIA praised the exchange programme of Chinese Muslim students with the al-Azhar University in Egypt and the CIA president met the Imam of the Grand Mosque in Mecca to discuss the Hajj, the annual Islamic pilgrimage.[98]

During the 2014 visit of Saudi Arabia’s King Salman to China the CIA was omnipresent in all official meetings and even during the guided tours to mosques and other Islamic centres. Following the visit, King Salman donated US$3 million to construct Islamic cultural centres in China.[99] In 2015, when the Turkish president made his first official visit to China and decided to meet Hui and Uyghur Muslim communities, Chinese officials welcomed the move.[100] Besides the broader strategic and economic aims, these guided tours by the CIA and broad-based religious engagement have helped China deflect major Muslim countries’ criticism on the internal prosecution of the Uyghurs.

Islamic Banking

China also exploited the Islamic banking system in economically rich Muslim countries through the BRI. After 30 major Muslim countries joined the BRI, Beijing relied on the Sharia principles of Islamic finance, which prohibits earning interest on loans and bars funding activities involving alcohol, pork, pornography or gambling.[101] Riding on Chinese investments, the Islamic finance market has made a steady growth, valued at US$2.6 trillion in 2016 and expected to grow to US$3.8 trillion in 2022. Many Chinese banks, including the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, have launched Sharia-based banking products in the Gulf and China. In 2016, Fullgoal Asset Management in Hong Kong partnered with UAE’s Mawarid Finance under Sharia principles.[102] Chinese mainland firms are also opting for Islamic finance. For example, HNA Group, which owns the well-known Hainan Airlines, borrowed US$150 million in Islamic loans in 2015.[103]

In 2018, the China-headquartered Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) signed a memorandum of understanding with the Islamic Development Bank Group to improve infrastructure connectivity in Asia using Islamic finance practices. The AIIB’s sixth annual meeting will be held in the UAE on 26-27 October 2021, further underscoring the growing comfort in the China-Muslim world relationship.[104] The Islamic banking and finance systems have helped China generate much-needed investments for the BRI projects and allowed the political elite in rich Muslim countries to safeguard their wealth.

Conclusion

Despite China’s widespread human rights violations against Uyghur Muslims, the economically indebted Muslim countries have conformed with Beijing’s strategy of political Islam, turning a blind eye to the atrocities in Xinjiang. BRI investments and loans have been used to suppress the Uyghur diaspora in the Muslim countries, with many states coerced to sign extradition treaties and deport Uyghur exiles to the Chinese mainland.

In the wealthy West Asian nations, China has exercised energy diplomacy, signed long-term investments in oil, and leveraged domestic political uncertainties in these countries to secure their silence on the Uyghur issue. While the CIA managed the perception of Islamic rulers, Islamic banking practices earned Beijing their respect. Islamic banking even helped West Asian royals diversify their investments in Chinese state-owned companies.

China’s approach in the Muslim world does not rely on an alliance system. Its strategic partnerships have developed a prudent and pragmatic case-by-case approach towards each country based on non-intervention, territorial integrity, and sovereignty. China has made deep inroads into the Muslim world and even influenced some neighbouring countries in South and Central Asia to replicate its Xinjiang model to varying degrees.

Western countries, Japan, and other democracies have repeatedly labelled the cultural prosecution of Uyghurs as a genocide. Some countries have even sanctioned several CCP officials and cut supply chain links to entities complicit in forced labour and other human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Trump’s ‘America first’ policy, anti-Muslim rhetoric, and moves like withdrawing from the Iran nuclear deal have fuelled these sentiments. This allowed China to proceed unchecked with its Xinjiang strategy.

The US-led western democracies and like-minded countries need to reinvest and reform their policies towards the Muslim world to regain their trust and halt China’s coercive-assertive hegemonic pursuits. This will help protect and save the prosecuted Muslim minorities in China and contain Beijing’s global ambitions.

[a] Major Muslim countries refer to Turkey, Iran, UAE, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman, Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, Malaysia, Iran, and the Central Asian republics. Other Muslim states like Indonesia, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and the Maldives have not made any comment on the Uyghur issue nor have signed the 2019 letter to the UN endorsing Chinese policies.

[b] A centrifugal tendency based on culture, history and geography pushes the Uyghurs to look outwards or seek independence, making it harder for Beijing to hold on to the Xinjiang province.

[1] Daniel S. Markey, China’s Western Horizon: Beijing and the New Geopolitics of Eurasia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020)

[2] He Yafei, “Chinese Overcapacity Crisis Can Spur Growth through Overseas Expansion,” South China Morning Post, January 7, 2014, https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/1399681/chinas-overcapacity-crisis-can-spur-growth-through-overseas

[3] “President Xi Jinping Delivers Important Speech and Proposes to Build a Silk Road Economic Belt with Central Asian Countries,” China.org.cn, November 1, 2013, http://www.china.org.cn/node_7064105/content_30468580.htm

[4] “China Steps up ‘strike Hard’ Campaign in Xinjiang,” Radio Free Asia, September 1, 2014, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/strike-hard-01092014172927.html

[5] Austin Ramzy, Chris Buckley, “THE XINJIANG PAPERS; ‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims”, The New York Times, November 16, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html

[6] Dr. Ewelina U. Ochab, “The Fate Of Uighur Muslims In China: From Re-education Camps To Forced Labor”, Forbes, April 4, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/ewelinaochab/2020/04/04/the-fate-of-uighur-muslims-in-china-from-re-education-camps-to-forced-labor/?sh=398fb9372f73

[7] “Xi Jinping wants building “great wall of iron” for troubled Xinjiang”, The Economic Times, March 11, 2017, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/xi-jinping-wants-building-great-wall-of-iron-for-troubled-xinjiang/articleshow/57594725.cms?from=mdr

[8] Ayjaz Wani, “Invest, indebt, incapacitate: Is China Replicating its ‘Xinjiang Model’ in BRI Countries?” Observer Research Foundation, Occasional Paper No. 268, (2020), https://www.orfonline.org/research/is-china-replicating-its-xinjiang-model-in-bri-countries/#_edn148

[9] Ayjaz Wani, Kashish Parpiani, “Human Rights and US Foreign Policy: Implications for India and China,” Observer Research Foundation, Issue Brief No. 462, (2021), https://www.orfonline.org/research/human-rights-and-us-foreign-policy-implications-for-india-and-china/

[10] Ayjaz Wani, “From cultural persecution to illegal organ harvesting in Xinjiang: Why is Muslim world silent?”, Observer Research Foundation, November 08, 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/from-cultural-persecution-to-illegal-organ-harvesting-in-xinjiang-why-is-muslim-world-silent-57403/

[11] Bradley Jardine, Edward Lemon and Natalie Hall, “No Space Left to Run: China’s Transnational repression of Uyghurs,” Uyghur Human Rights Project and Oxus Society for Central Asia Affairs, (2021) https://oxussociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/transnational-repression_final_2021-06-24-1.pdf

[12] Turan Kayaoglu, “The Organization of Islamic Cooperation’s Declaration on Human Rights: Promises and Pitfalls,” Brookings, September 28, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-organization-of-islamic-cooperations-declaration-on-human-rights-promises-and-pitfalls/

[13] Owen Lattimore, Pivot of Asia: Sinkiang and the Inner Asian Frontiers of China and Russia, (Boston: Little & Brown, 1950)

[14] Donald H. Mcmillen, Chinese Communist Power and Policy in Xinjiang 1949-1977, (Colorado , Westview Press Westview Press, 1979)

[15] Donald E. Maclnnis (ed.), Religious Policy and Practice in Communist China: A Documentary History, (London: Macmillan, 1972)

[16] Dillon, Michael., Xinjiang-China’s Muslim Far Northwest, (London: Routledge Curzon, 2004)

[17] Eric Hobsbawn, “Nations and Nationalism Since 1780” (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990)

[18] Jack Chen, The Sinkiang Story (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1977)

[19] Debasish Chaudhuri, “Minority Economy in Xinjiang- A Source of Uyghur Resentment,” China Report, 46(9) (2010)

[20] Ayjaz Ahmad Wani, Socio-Economic Impact of Han Migration on Xinjiang, Romanian Journal of Eurasian Studies, Vol. X, No. 1-2 (2014), PP, 215-232

[21] Religion in the People’s Republic of China, Documentation, No. 10, March 1983:7.

[22] Gaye Christoflersen, “Xinjiang and the Great Islamic Circle: The Impact of Transnational Forces on Chinese Regional Planning”, The China Quarterly, No.133, (1993), pp.130-151.

[23] Mahnaz Z. Ispahani, Roads and Rivals: The Political Uses of Access in the Borderlands of Asia, Cornell University Press. 1989.

[24] Christoffersen, “Xinjiang and Great Islamic Circle”.

[25] Michael Winchester, “China vs Islam”, Asia week, 23(42) (1997)

[26] Ayjaz Ahmad Wani, “Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Islam in China during 20th century: A Case Study of Xinjiang”, Central Asia, University of Peshawar, 73 (2013), http://asc-centralasia.edu.pk/old_site/Issue_73/04_ayjazwani.html

[27] Zia Ur Rehman, “ETIM’s presence in Pakistan and China’s growing pressure”, NOREF Report, August 2014, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/183175/381280b226170116bb6f07dc969cb17d.pdf

[28] Anti-Crime Campaigns and Religious Repression, HRW Reports, 2005, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2005/china0405/9.htm#_ftn163

[29] Justin Jon Rudelson, Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China’s Silk Road, (New York : Columbia University Press, 1997)

[30] John Pomfret, “Separatists Defy Chinese Crackdown”, Washington Post, January 26, 2000, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/WPcap/2000-01/26/016r-012600-idx.html

[31] Human Rights Watch, We are afraid to even look for them: Enforced disappearance in the wake of Xinjiang’s Protest” October 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2009/10/20/we-are-afraid-even-look-them/enforced-disappearances-wake-xinjiangs-protests

[32] Matthew D. Moneyhon, “China’s Great Western Development Project in Xinjiang: Economic Palliative or Political Trojan Horse”, Denver Journal of International Law & Policy, 31(3) (2020), https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/323046873.pdf

[33] Altay Atli, “The Role of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the Economic Security of China”, The Journal of Turkish Weekly, 6(11) (2011).

[34] Moneyhon, “China’s Great Western Development Project in Xinjiang

[35] Masahiro Hoshino, “Preferential policies for China’s ethnic minorities at a crossroads”, Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 8(1) (2019), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/24761028.2019.1625178?needAccess=true

[36] “Riots in Western China Amid Ethnic Tension,” The New York Times, July 06, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/06/world/asia/06china.html

[37] Human Rights Watch, We are afraid to even look for them: Enforced disappearance in the wake of Xinjiang’s Protest” October 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2009/10/20/we-are-afraid-even-look-them/enforced-disappearances-wake-xinjiangs-protests

[38] “World Uyghur Congress’ Statement on July 5th Urumqi Incident,” July 7, 2009, http://www.uyghurcongress.org/En/PressRelease.asp?ItemID=-1553700856&mid=1096144499

[39] Kathrin Hille, “Xinjiang widens crackdown on Uighurs,” Financial Times, July 19, 2009, https://www.ft.com/content/5aa932ee-747c-11de-8ad5-00144feabdc0

[40] Rudelson, Oasis Identities, pp. 39-41,

[41] Chris Buckley, “27 Die in Rioting in Western China,” The New York Times, June 26 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/27/world/asia/ethnic-violence-in-western-china.htm

[42] Four sentenced in China over Kunming station attack, BBC, 12 September, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-29170238

[43] “Tracking China’s Muslim Gulag,” Reuters, November 27, 2018,https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/muslims-camps-china

[44] “China Has Turned Xinjiang into a Police State like No Other,” The Economist, May 31, 2018, https://www.economist.com/briefing/2018/05/31/china-has-turned-xinjiang-into-a-police-state-like-no-other

[45] Amie Ferris-Rotman, “Abortions, IUDs and Sexual Humiliation: Muslim Women Who Fled China for Kazakhstan Recount Ordeals”, The Washington Post, October 5, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/abortions-iuds-and-sexual-humiliation-muslim-women-who-fled-china-for-kazakhstan-recount-ordeals/2019/10/04/551c2658-cfd2-11e9-a620-0a91656d7db6_story.html

[46] Adrian Zenz, “Sterilizations, IUDs, and Coercive Birth Prevention: The CCP’s Campaign to Suppress Uyghur Birth Rates in Xinjiang”, China Brief, 20(12) (2020), The James Town Foundation, https://jamestown.org/program/sterilizations-iuds-and-mandatory-birth-control-the-ccps-campaign-to-suppress-uyghur-birth-rates-in-xinjiang/

[47] “Forced sterilisation and Xinjiang’s shrinking population”, France 24, May 5, 2021, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20210519-forced-sterilisation-and-xinjiang-s-shrinking-population

[48] Ruth Ingram, “Rape, Humiliation, and Torture: A Uyghur-Kazakh Survivor Speaks Out”, Bitter Winter, June 1, 2021, https://bitterwinter.org/rape-humiliation-and-torture-a-uyghur-kazakh-survivor-speaks-out/

[49] Matthew Hill, David Campanale and Joel Gunter, “Their goal is to destroy everyone’: Uighur camp detainees allege systematic rape” BBC, 02 February, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-55794071

[50] Benedict Rogers, “The Nightmare of Human Organ Harvesting in China”, The Wall Street Journal, February 5, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-nightmare-of-human-organ-harvesting-in-china-11549411056

[51] “China Uighurs ‘moved into factory forced labour’ for foreign brands”, BBC, 02 March, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-51697800

[52] Anthony Blair, “Coronavirus: China ‘harvesting organs from detained Muslims’ to treat patients”, Daily Star, March 11, 2020, https://www.dailystar.co.uk/news/world-news/coronavirus-china-harvesting-organs-detained-21671170

[53] Timothy Grose, Twitter, June 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/grosetimothy/status/1399742957255864321?s=24

[54] Timothy Grose, Twitter, June 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/grosetimothy/status/1399742957255864321?s=24

[55] Gerry Shih, “China’s Mass Indoctrination Camps Evoke Cultural Revolution,” Associated Press, May 18, 2018, https://apnews.com/article/6e151296fb194f85ba69a8babd972e4b

[56] Chris Buckley and Austin Ramzy, “Facing Criticism Over Muslim Camps, China Says: What’s the Problem?”, The New York Times, December 9, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/09/world/asia/china-camps-muslims.html

[57] Andrew Sharp, “Xinjiang Denies Existence of Uighur Detention Camps in China,” Nikkei Asia, March 12, 2019, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/China-People-s-Congress/Xinjiang-denies-existence-of-Uighur-detention-camps-in-China

[58] Lindsay Maizland, “China’s Repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang”, Council On Foreign Relations (CFR), March 1, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-repression-uyghurs-xinjiang

[59] ANI, “Lithuanian parliament latest to term China’s treatment of Uyghurs ‘genocide”, May 21, 2021, https://www.aninews.in/news/world/europe/lithuanian-parliament-latest-to-term-chinas-treatment-of-uyghurs-genocide20210521005712/

[60] Deirdre Shesgreen, “The world’s on fire’ and other takeaways from Biden’s secretary of state nominee confirmation hearing”, USA TODAY, January 19, 2021, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/elections/2021/01/19/biden-nominee-antony-blinken-china-committing-genocide-uyghurs/4215835001/

[61] “Xinhua Commentary: Why Xinjiang Cotton?,” Xinhua News, April 1, 2021, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-04/01/c_139852360.htm

[62] Ben Westcott & Jo Shelley, “22 countries sign letter calling on China to close Xinjiang Uyghur camps”, CNN, July 11, 2019,https://edition.cnn.com/2019/07/11/asia/xinjiang-uyghur-un-letter-intl-hnk/index.html

[63] Joshua Berlinger, “North Korea, Syria and Myanmar among countries defending China’s actions in Xinjiang”, CNN, July 15, 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/07/15/asia/united-nations-letter-xinjiang-intl-hnk/index.html

[64] Joshua Berlinger, “North Korea, Syria and Myanmar among countries defending China’s actions in Xinjiang”, CNN, July 15, 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/07/15/asia/united-nations-letter-xinjiang-intl-hnk/index.html

[65] Ben Westcott & Isil Sariyuce, “Erdogan Says Xinjiang Camps Shouldn’t Spoil Turkey-China Relationship,” CNN, July 5, 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/07/05/asia/turkey-china-uyghur-erdogan-intl-hnk/index.html

[66] Cristina Maza, “Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed Bin Salman Defends China’s Use of Concentration Camps for Muslims,” Newsweek, February 23, 2019, https://www.newsweek.com/saudi-arabia-mohammad-bin-salman-defends-china-concentration-camps-muslims-1340592

[67] Meenakshi Ray, “Imran Khan again ignores China’s treatment of Uighurs, says accepts ‘Chinese version’”, Hindustan Times, July 02, 2021, https://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/imran-khan-again-ignores-china-s-treatment-of-uighurs-101625190434534.html

[68] Ayjaz Wani, “China-Turkey extradition treaty and implications on Uyghurs,” Observer Research Foundation, January 5, 2021, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/china-turkey-extradition-treaty-implications-uyghurs/

[69] Jardine, Lemon & Hall, “No Space Left to Run”, https://oxussociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/transnational-repression_final_2021-06-24-1.pdf

[70] “The 21 most authoritarian regimes in the world”, Business Insider, 05 February, 2020, https://www.wearethemighty.com/lists/the-21-most-authoritarian-regimes-in-the-world/

[71]Mustafa Akyol, “Freedom in the Muslim World”, Cato Institute, August 25, 2020, https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/2020-08/EDB_33_v3.pdf

[72] Akyol, “Freedom in the Muslim World”

[73] United States Department of State, “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2018 ,” Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, 2018, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/SAUDI-ARABIA-2018.pdf

[74] “Military Whisked Away 568 persons and Killed Another 241”, Human Rights Council of Balochistan, 2019, http://hakkpaan.org/balochistan-2019-military-whisked-away-568-persons-and-killed-another-241/

[75] Human Rights Watch, “Turkey Events of 2019” World Report 2020, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/turkey

[76] Human Rights Watch, “Iran Events of 2020” World Report 2020, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/iran

[77] United States Department of State, “UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT 2019”, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, 2019, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/UNITED-ARAB-EMIRATES-2019-HUMAN-RIGHTS-REPORT.pdf

[78] Jenna Johnson & Abigail Hauslohner, “‘I think Islam hates us’: A timeline of Trump’s comments about Islam and Muslims”, The Washington Post, 20 May, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2017/05/20/i-think-islam-hates-us-a-timeline-of-trumps-comments-about-islam-and-muslims/

[79] David Brunnstrom, “Trump cuts more than $200 million in U.S. aid to Palestinians”, Reuters, 25 August, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-palestinians-idUSKCN1L923C

[80] Walter Russell Mead, “Imperialism Will Be Dangerous for China,” Wall Street Journal, September 17, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/imperialism-will-be-dangerous-for-china-1537225875

[81] Jonathan Hillman, China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Five Years Later, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington DC, 2018, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-five-years-later-0

[82] World Bank Group, Belt and Road Initiative, Washington DC, March 28, 2018, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/brief/belt-and-road-initiative

[83] Betha McKernan, “I miss my homeland: fearful Uighurs celebrate Eid in exile in Turkey,” The Guardian, May 24, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/24/fearful-uighurs-celebrate-eid-in-exile-in-turkey

[84] Sinan Tavsan, “Eyeing Chinese investment, Turkey kicks off Canal Istanbul project,” Nikkei Asia, June 28, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Eyeing-Chinese-investment-Turkey-kicks-off-Canal-Istanbul-project

[85] Jonathan Fulton, “China’s Changing Role in the Middle East,” Atlantic Council, June 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Chinas_Changing_Role_in_the_Middle_East.pdf

[86] Fulton, “China’s Changing Role in the Middle East”

[87] Daniel Workman, “Crude Oil Imports by Country,” World’s Top Exports, 2019, http://www.worldstopexports.com/crude-oil-imports-by-country/

[88] US Energy Information Agency, “International Energy Outlook 2019 with Projections to 2050,” September 2019, https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/ieo/pdf/ieo2019.pdf

[89] Keith Bradsher, “China is trying to tame inflation. It matters to much of the globe”, The Economic Times, June 9, 2021, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/china-is-trying-to-tame-inflation-it-matters-to-much-of-the-globe/articleshow/83360967.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

[90] Daniel Workman, “Top 15 Crude Oil Suppliers to China”, World’s Top Exports, https://www.worldstopexports.com/top-15-crude-oil-suppliers-to-china/

[91] “Oil dependence and US Foreign Policy,” Council for Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/timeline/oil-dependence-and-us-foreign-policy

[92] “Oil dependence and US Foreign Policy”

[93] Jonathan Hoffman, “Moscow, Beijing, and the Crescent: Russian and Chinese religious soft power in the Middle East” Domes Digest of Middle East Studies, 31 (2) (2021).

[94] Hoffman, “ Moscow, Beijing, and the Crescent”

[95] “37 countries defend China over Xinjiang in UN letter” France24, July 12, 2019.

[96] Lucille Greer, Bradley Jardine, “The Chinese Islamic Association in the Arab World: The Use of Islamic Soft Power in Promoting Silence on Xinjiang”, Middle East Institute, 14 July 2020.

[97] Liu Xin, “Chinese govt actively supports Islamic education in Xinjiang: Scholar”, Global Times, February 08, 2021.

[98] Greer, Jardine, “The Chinese Islamic Association in the Arab World,” Middle East Institute, July 14, 2020.

[99] Jonathan Hoffman, “Why do some Muslim-majority countires support China’s crackdown on Muslims?” The Washington Post, 04 May 2021.

[100] Enes Kaplan, “Trade focus of Erdogan China trip, but Uighur discussed,” Anadolu Agency, 29 July 2015.

[101] Huileng Tan & Evelyn Cheng, “Beijing’s Belt and Road plans could boost the Islamic banking sector”, CNBC, 20 August 2019.

[102] Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, “The Rise of Islamic Finance on China’s Belt and Road”, The Diplomat, 15 February 2019.

[103] “China expands overseas economic clout through Islamic Finance,” MCI Halala International Holdings Limited, January 25, 2016.

[104] “AIIB to hold its first annual meeting in the Middle East in the UAE,” Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, July 28, 2020.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV