At no point in the past has China laid claim to the entire Galwan Valley, a sliver of flat land abutted by steep gorges through which the Galwan river flows and enters the Shyok river, and the maps Beijing has itself published in the past show its claim line stopping short of the confluence.

Earlier this week, however, in the wake of bloody clashes between the Indian and Chinese armies in which 20 Indian soldiers were killed and China too suffered an unknown number of casualties, both the Peoples Liberation Army and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing have described the Galwan Valley as part of China’s territory.

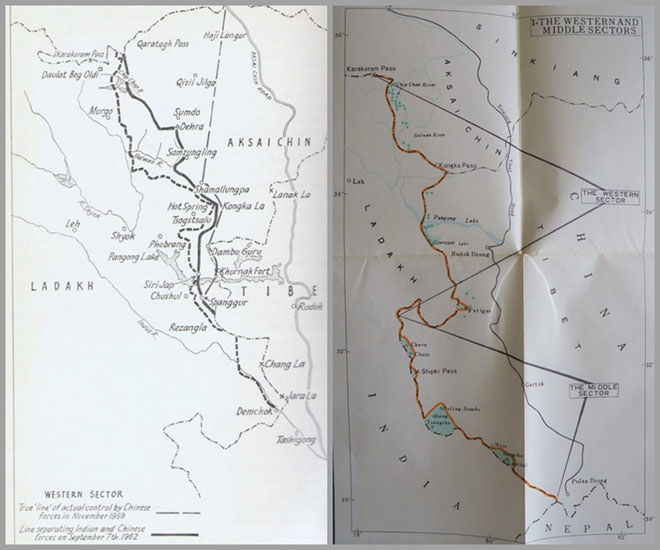

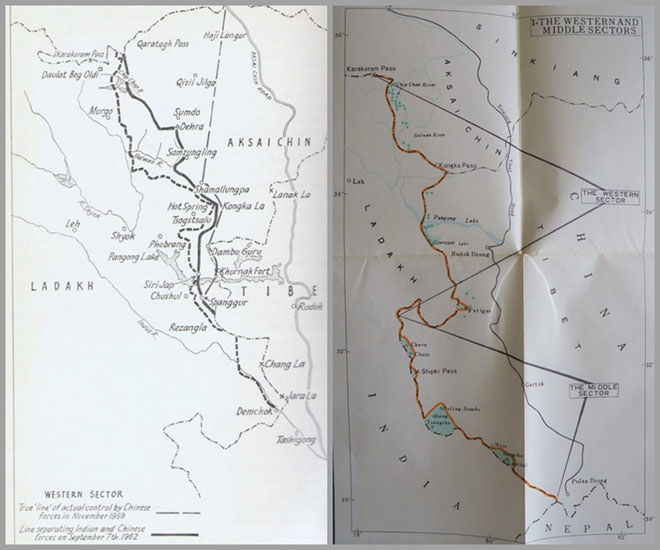

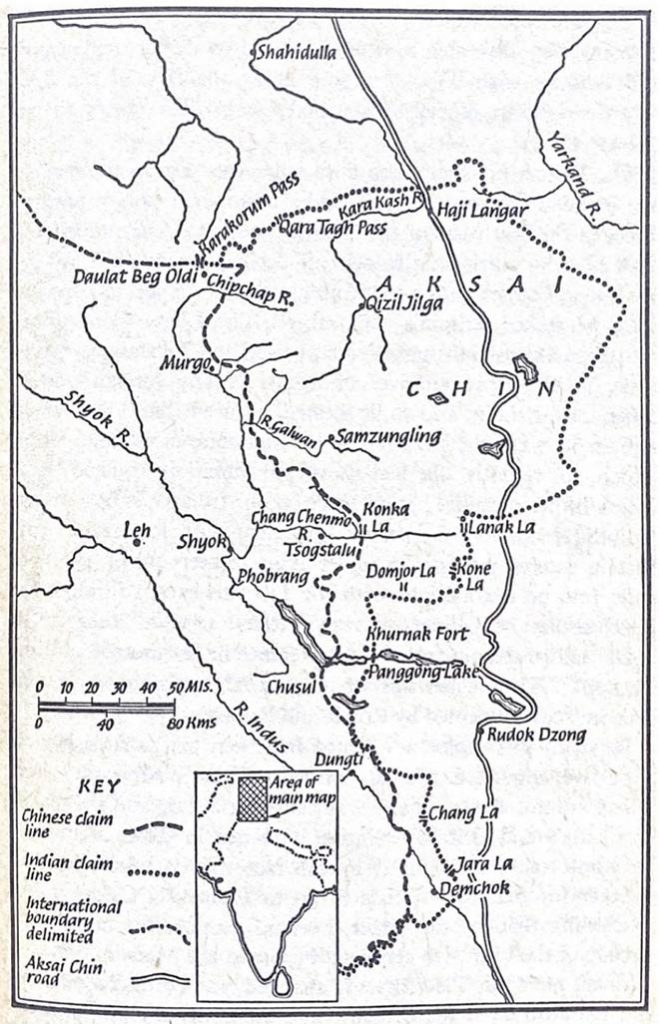

China’s claim line stops short of the confluence of the Galwan and Shyok rivers, encompassing most but not all of the Galwan valley. Lines of Actual Control have varied over the years and in many ways have been notional. When there were no roads, the LAC was merely a line connecting the scattered posts. On the right, a Chinese map issued in the midst of the 1962 war indicating what they claim were Indian incursions (blue dots) Source: Dorothy Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers (1969) for map on left and the Foreign Languages Press, Peking 1974 publication of Premier Zhou’s letter to Afro-Asian leaders on the Sino-Indian boundary issue on November 15, 1962, for map on the right.

China’s claim line stops short of the confluence of the Galwan and Shyok rivers, encompassing most but not all of the Galwan valley. Lines of Actual Control have varied over the years and in many ways have been notional. When there were no roads, the LAC was merely a line connecting the scattered posts. On the right, a Chinese map issued in the midst of the 1962 war indicating what they claim were Indian incursions (blue dots) Source: Dorothy Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers (1969) for map on left and the Foreign Languages Press, Peking 1974 publication of Premier Zhou’s letter to Afro-Asian leaders on the Sino-Indian boundary issue on November 15, 1962, for map on the right.

The Galwan river is named after Ghulam Rassul Galwan, a Ladakhi adventurer who accompanied many European explorers in the region at the turn of the 19th century. According to Ladakhi history the Galwan Nullah was named so by British geologists after he discovered a passage through what seemed like an impenetrable set of gorges.

Over the years, the status of the Galwan Valley has changed and, if the recent developments are to be taken into account, it is still changing.

Commenting on the incident of July 15, the official spokesman of the Western Theatre Command of the PLA, Zhang Shuili, accused the Indian side of “deliberately launching a provocative attack” and he went on to add that “the sovereignty of the Galwan Valley has always belonged to China.”

India, of course, disagrees with this claim, and the Special Representatives process was designed to help the two countries resolve their differences over the boundary question. Linked to this process is the line of actual control, or LAC, which is not a line on the ground or even an agreed line on a map – which is why it is susceptible to changes by one side or the other. Over the years, a familiar pattern has built up around specific problem areas along the LAC but the Galwan Valley has not been one of them.

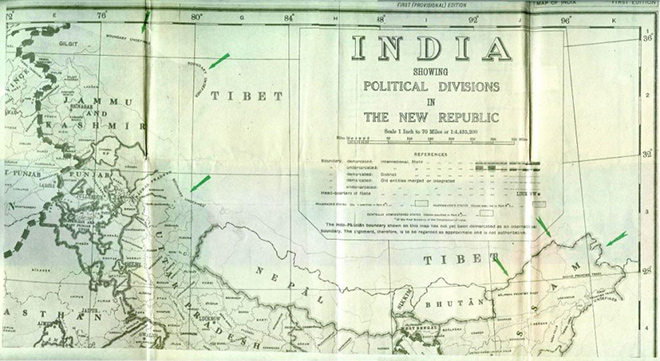

While the earliest map issued by India after independence showed the countries borders in Aksai Chin as undefined, the present boundaries of what is now the Union Territory of Ladakh were drawn unilaterally in 1954.

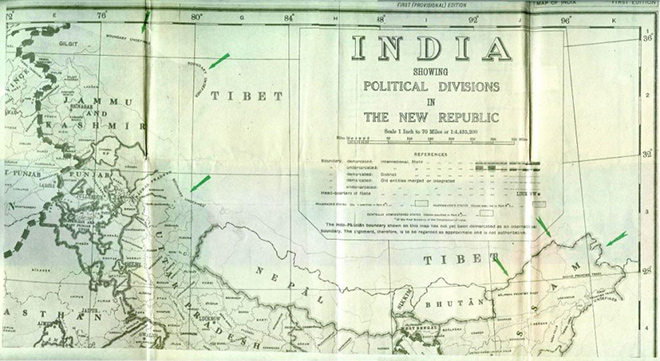

The Government of India’s official map of India and its neighbours, issued in 1950.

The Government of India’s official map of India and its neighbours, issued in 1950.

As for the Chinese, different maps showed Aksai Chin sometimes in their territory, sometimes outside. But they needed the area to build an all-weather road from Xinjiang to facilitate their assimilation of Tibet. And they did this over several years in the early 1950s.

In the 1950s, Indian patrols rarely ventured into the inhospitable region where there is no human habitation. The history of India’s inability to prevent the construction of China’s highway from Xinjiang to Tibet through the region is well known, as is the fact that New Delhi only learnt of the development years after it had occurred.

Today, we talk about the LAC, but at the time there was virtually no Chinese presence in the area around Galwan. When we talk of the “line of actual control” we are talking of a line that connects the dots on the maps indicating isolated posts of both sides, some being held by 20-30 persons in that vast area.

The Chinese established a post at Samzungling at the head of the Galwan river before India could some time in 1959. As part of its misguided ‘forward policy’, India tried to cut off the Chinese post by planting one of its own. Army HQ overruled the Western Command headquarters and insisted that the post be set up. In the winter of 1961, an effort to go up the river valley failed, so a platoon of Gorkhas was sent up from the Hot Springs area in the south. After a month’s march, the group reached the upper reaches of the Galwan Valley and established themselves on July 5, 1962, cutting off the Chinese post down river and even blocking a Chinese supply party to the post.

There was an exchange of diplomatic notes with a stiff Chinese protest on July 8. India’s response was that it had always been patrolling the area and accused the Chinese of “incessant intrusions” into Indian territory. On July 10, some 70 Chinese soldiers surrounded the Indian post and later increased their strength to a battalion. The post was now cut off and columns sent overland to supply it in mid-July were intercepted. Eventually, it had to be supplied by air. On the morning of October 20, 1962, it was wiped out, along with other posts set up in Chip Chap river valley up north.

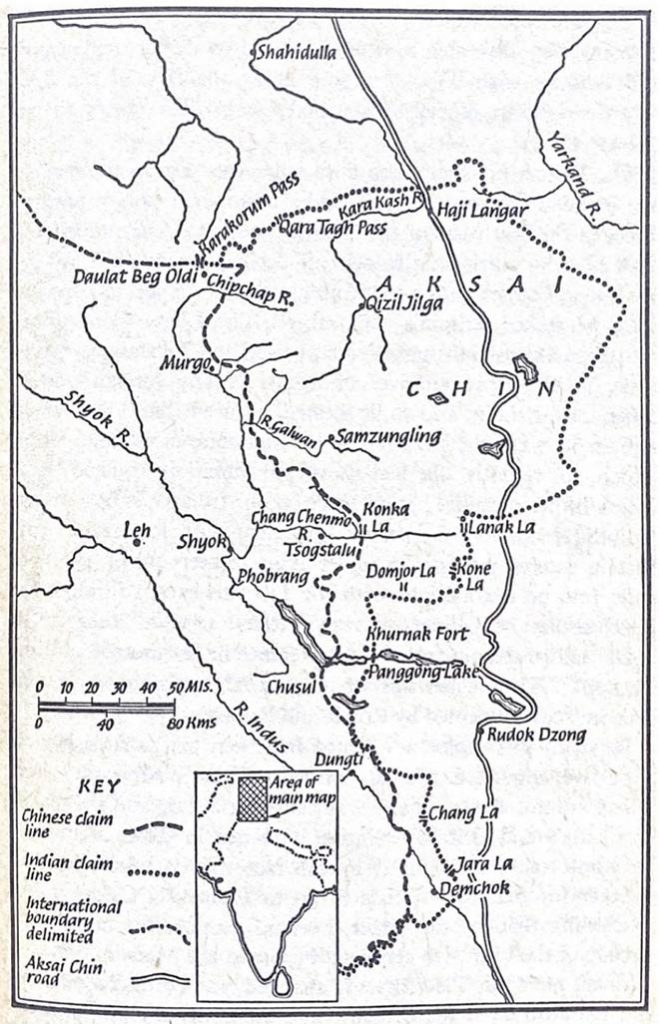

Map showing ‘Historical development of Western Sector Boundary’. Source: Neville Maxwell, India’s China War (Pelican, 1972)

Map showing ‘Historical development of Western Sector Boundary’. Source: Neville Maxwell, India’s China War (Pelican, 1972)

Incidentally, the Henderson-Brooks report notes that in the discussions before sending the forces to evict the Chinese from the Thag La pass north of Tawang, the government was willing to accept a loss of certain territory in Ladakh. Indeed, the report notes that even while the operation at Thag La – the event that triggered the Sino-Indian war of 1962 – was being planned, there was little or no attention paid to shoring up the isolated posts in Ladakh. They were simply asked to be prepared for some Chinese reactions on the forward posts and their orders were to “fight it out and inflict maximum casualties on the Chinese.”

Following the war, the Chinese said they were carrying out a 20 km withdrawal behind their frontlines. There were no Indian forces in that region anywhere so it didn’t really matter. It is only in the 1980s that India began to re-establish itself along the LAC, but in areas like the Galwan Valley it was constrained by the terrain.

Chinese claims in the Aksai Chin were confusing and sometimes contradictory. But, at the end of the day, they had physical control of the territory and easier access to it than India. Maps in the 1950s often showed the Chang Chenmo Valley within India. In 1959, Zhou Enlai confirmed that a map published in 1956 was the correct alignment. This map showed the Galwan and Chip Chap river valleys to be parts of India. It was only in their sixth meeting with Indian officials in June 1960 that the Chinese put out what they said was their official map which included the two valleys as part of Chinese territory.

Since 1993, both India and China have maintained the fiction of a “Line of Actual Control” in the area, which was all right till the other day. Suddenly the Chinese have decided that the entire Galwan Valley is part of their territory.

The Chinese goal now seems to be to establish their boundary along the Shyok river, as it seems to be to push forward and control all of the north bank of Pangong Lake constraining Indian defences relating to the Leh region. As for the LAC, to paraphrase Humpty Dumpty, it is where you choose it to be.

This commentary originally appeared in The Wire.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

China’s claim line stops short of the confluence of the Galwan and Shyok rivers, encompassing most but not all of the Galwan valley. Lines of Actual Control have varied over the years and in many ways have been notional. When there were no roads, the LAC was merely a line connecting the scattered posts. On the right, a Chinese map issued in the midst of the 1962 war indicating what they claim were Indian incursions (blue dots) Source: Dorothy Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers (1969) for map on left and the Foreign Languages Press, Peking 1974 publication of Premier Zhou’s letter to Afro-Asian leaders on the Sino-Indian boundary issue on November 15, 1962, for map on the right.

China’s claim line stops short of the confluence of the Galwan and Shyok rivers, encompassing most but not all of the Galwan valley. Lines of Actual Control have varied over the years and in many ways have been notional. When there were no roads, the LAC was merely a line connecting the scattered posts. On the right, a Chinese map issued in the midst of the 1962 war indicating what they claim were Indian incursions (blue dots) Source: Dorothy Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers (1969) for map on left and the Foreign Languages Press, Peking 1974 publication of Premier Zhou’s letter to Afro-Asian leaders on the Sino-Indian boundary issue on November 15, 1962, for map on the right. The Government of India’s official map of India and its neighbours, issued in 1950.

The Government of India’s official map of India and its neighbours, issued in 1950. Map showing ‘Historical development of Western Sector Boundary’. Source: Neville Maxwell, India’s China War (Pelican, 1972)

Map showing ‘Historical development of Western Sector Boundary’. Source: Neville Maxwell, India’s China War (Pelican, 1972) PREV

PREV