-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

In two sets of visits to the Central Asian region in 2013 and 2014, Xi Jinping set a scorching pace for Modi to follow. Unfortunately for India, even a super-star Prime Minister cannot do the impossible. He lacks the vast investible resources that China has already deployed and is deploying in the region.

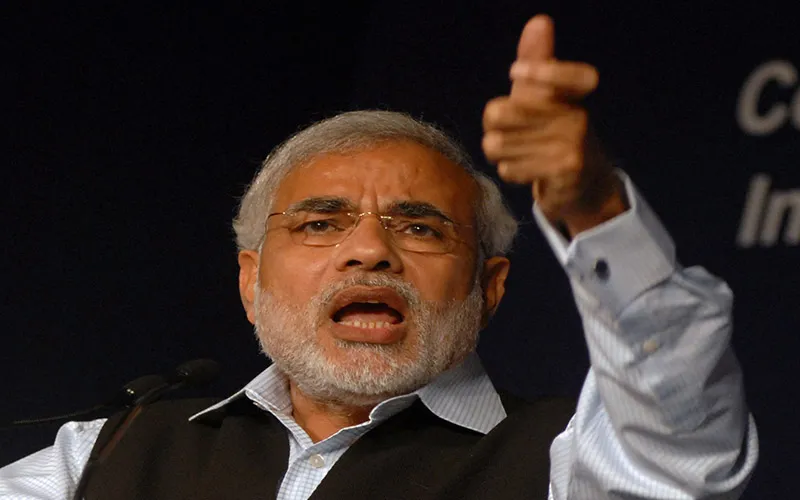

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's visit to Central Asia is a case of attempting to play catch up with China. But a five-country, five-day visit is hardly likely to achieve its objective. Nevertheless, considering the geopolitical importance of the region, such visits are welcome, provided India is able to follow up initiatives launched during the visit.

A side show of the visit will be India's formal induction into the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), the only central Asian regional grouping of its kind at a meeting in Ufa on July 9-10. The SCO is no NATO, at least as yet. But it is important for India to be part of the organization because it helps India to maintain its important Russian linkage and prevent a too-precipitate Russia-China axis.

In two sets of visits to the region in 2013 and 2014, China's president Xi Jinping set a scorching pace for Modi to follow. Unfortunately for India, even a super-star Prime Minister cannot do the impossible. He lacks the vast investible resources that China has already deployed and is deploying in the region, as part of its Belt Road Initiative and, more important, India, lacks geographical contiguity with the region. Given our legal claim to Jammu and Kashmir, India does have a border with Afghanistan and can connect with Central Asia, but this crucial territory is occupied by Pakistan the basis of whose national policy is to deny India any access to Afghanistan and Central Asia. If India can use the instrumentality of the SCO to get Islamabad to open up, it will be a great achievement.

China's enormous resources which are being deployed in the construction of what they call the Silk Road Economic Belt are enormous. In 2000, China's total trade with Central Asia was estimated to be some $ 1 billion. By 2010 it has increased 30 times, and today it is of the order of $ 50 billion. The key turning point where China overtook Russia as the primary trade partner of the region occurred during the 2008 financial crisis.

In this period, China has built key infrastructure in the region, specifically two new energy pipelines—the Atyrau-Alashankou oil pipeline across Kazakhstan and the China-Central Asia gas pipeline. The consequences of this have been enormous, for example the gas pipeline which was inaugurated in 2009, broke Russia's monopoly in the region, taking gas from three lines that originate in Turkmenistan, across Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan into China's eastern network. A fourth line from Tajikstan will soon get underway and in a few years, China will get some 30 per cent of its gas supply from Central Asia.

In addition, China has built new highways, rail networks and has emerged as a major source of development and emergency finance for the region. With the establishment of the New Development Bank and the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, the process of integrating the region into China's economic and financial sphere will accelerate. The economic face of the region is already towards China, but China is sensitive to Russian concerns when it comes to political and security issues. As of now there is a distribution of labour between the two countries wherein Russia remains the primary security provider and China the economic benefactor of the region.

For China all this serves a dual purpose. At one level it shields its sensitive province of Xinjiang from radical influences in Central Asia. On the other, it enables it to play a role in developing connectivity that leads to markets in Europe through routes that avoid the American-dominated oceans. Freight trains are already carrying Chinese products to European markets and the Chinese are hoping to further enhance the quality of the connectivity. But for this to become economically viable, there must be a two-way flow on the Silk Route, a somewhat distant goal as of now.

All this poses a challenge not just to India, but the United States as well. Initially the US was happy with China reducing Russian influence in the region, but now after Ukraine and the emergence of a Russia-China axis, the Americans are concerned that the integration of the region with China will add greater heft to the Chinese-Russian efforts to counter-balance to the US and the West.

Political geography limits India's role in the region. At $ 1 billion, India's trade is one fiftieth of that of China in the region. Modi's focus in the visit is energy resources like gas, oil and uranium of countries like Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. The problem that India confronts is connectivity. The TAPI pipeline which could bring Turkmen gas to India is bedeviled by the political conditions of Afghanistan, as well as Pakistan's general blockade of India.

The way out for India is to develop its corridor to Central Asia and Afghanistan through Iran. India would like to link its western ports of Mumbai and Kandla through a north-south rail corridor using Iranian ports of Chah Bahar and Bandar Abbas, all the way to Russia with branch lines to the Central Asian republics. However, this requires a huge monetary outlay, as there are missing sections in the existing rail networks. But more than that, it requires active diplomacy and effective project management. The reality is that while India's goals remain plans, the Chinese are already on the ground and running.

The bigger problem is, however, geopolitics. India's initiatives towards Teheran have been limited by the stand off between the West and Iran over the nuclear issue which has made it difficult for India to invest in projects like the development of the Chah Bahar port. The sanctions on Iran could be lifted soon, but the Iranians are not likely to forget that New Delhi has broadly sided with the US in the last decade or so.

But why blame the nuclear issue? Even before that New Delhi has been tardy in putting down serious money for Chah Bahar. It was only a Chinese offer of $ 100 million in 2013 that prompted India to finally put down $85.2 billion last year. But this is not enough, given the enormity of the requirements in developing the North-South corridor and its ancillary East-West wings. More important is the task of prioritizing India's geopolitical needs and addressing them effectively.

The Prime Minister would do well to consider a visit to Teheran soon. But before that, he needs to get his geopolitical focus clear because any visit to Iran must be balanced with ties to Israel, the country that Mr Modi is likely to visit earlier. But dealing with the Israel-Iran issue is not an impossible task as both Teheran and Tel Aviv are pragmatic powers and both are in their own way important to the country. But India is not going to get a free ride from either of them and managing the triangular relationship is the challenge that New Delhi must step out and confront.

(The writer is a Distinguished Fellow at Observer Research Foundation, Delhi)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Manoj Joshi is a Distinguished Fellow at the ORF. He has been a journalist specialising on national and international politics and is a commentator and ...

Read More +