-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Sikh extremism and separatism are far from the norm, but they have somehow hijacked Canadian diplomacy

India’s escalating diplomatic tensions with Canada over the alleged nefarious activities of a group of extremist Sikhs has again turned the spotlight on India’s large Sikh diaspora. It has also raised questions about the nature of domestic politics in Canada and the circumstances that led Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to make his extraordinary statement in Canada’s parliament on September 18, claiming that the Indian government could have been behind the killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar in Surrey, British Columbia, on June 14, 2023.

Mr Trudeau’s comments drew a predictably sharp reaction from India and sent relations with Canada into a tailspin. Understanding the escalating row requires a bit of perspective about the Sikh community, whose homeland is in Punjab, India, and whose largest diaspora community is in Canada.

Sikhs constitute less than 2 per cent of India’s population, and were among the most affected communities by the trauma of Partition in 1947, when Punjab was divided between India and Pakistan. But the community has since re-established itself, and produced sports and business leaders and even a prime minister and a president of India.

It has also managed to overcome the harrowing memories of the 1980s and their horrifying cycle of violence, with an armed faction seeking greater autonomy or an independent Khalistan, the brutal repression of the movement by security agencies, the desecration of the Golden Temple in Amritsar during Operation Blue Star in June 1984, the anti-Sikh pogroms in Delhi and elsewhere after prime minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by Sikh bodyguards later that year, and the lack of progress in bringing the perpetrators of the pogroms to justice.

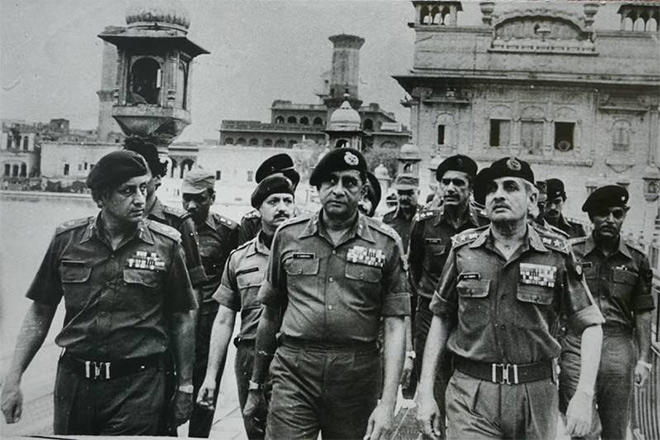

Senior Indian army officers at the site of Operation Blue Star, in the Golden Temple in Amritsar, India, in 1984.

But Punjab has since risen to become one of the most peaceful parts of India even though it struggles against formidable social and economic challenges. The Khalistan demand finds no traction with the public today. When Punjab voted in 2022 to give a landslide majority to the small Aam Aadmi Party, the one party that campaigned on a platform seeking a quasi-autonomous (not independent) status for Punjab got a mere 2.46 per cent of the votes.

Most Sikhs living in Punjab and elsewhere in India strongly identify themselves as Indians and don’t want any kind of Khalistan

Indeed, a Pew Research poll in 2021 showed that “Sikhs also are overwhelmingly proud of their Indian identity. A near-universal share of Sikhs say they are very proud to be Indian [95 per cent], and the vast majority [70 per cent] say a person who disrespects India cannot be a Sikh”.

So, if most Sikhs living in Punjab and elsewhere in India strongly identify themselves as Indians and don’t want any kind of Khalistan, what drives separatist demands from a minuscule section of the Sikh diaspora living thousands of miles away from Punjab?

The effectiveness of the Khalistan campaign lies in its ability to conflate the real issues of 1984 with the mythological ones of an independent homeland for the Sikhs. As a diplomat, I tried to deal with this dichotomy during my stint in Australia. Each year on June 6, a largish throng of Sikhs would come to the High Commission offices in Canberra and protest against the desecration of the Golden Temple during Operation Blue Star and the delay in punishing those responsible for the pogroms in 1984. A few would also raise pro-Khalistan slogans and banners.

I took up the matter with a prominent local leader of the Sikh community and we arrived at a simple compromise. As members of the Indian diaspora, they could legitimately raise their concerns about Operation Blue Star and the delay in serving justice. I would receive their memorandum and faithfully relay it to Delhi. However, this would be on the explicit assurance that there would be no Khalistani slogans or banners. That worked well and quite a bit of the discontent quickly evaporated.

But the problem in Canada is more complex. During Mr Trudeau’s 2018 visit to India, Capt Amarinder Singh, the Sikh chief minister of Punjab, handed him a list of nine suspected terrorists who had found safe haven in Canada and were thought to be using their sanctuary to sponsor targeted killings of political and gang-related opponents in Punjab. India’s investigative agencies followed up with detailed dossiers but there was no response.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and NDP leader Jagmeet Singh take part in an election debate in Gatineau, Canada, in 2021.

And this year, extremists in Canada put out posters with the photographs and names of the Indian High Commissioner in Canada, the ambassador to the US and other senior diplomats. Most egregiously, they used a festive parade to present a float that eulogised the killers of Mrs Gandhi.

Canadian police and security agencies have done little to intercede. And that’s what India finds so galling when it comes to the specific case of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, often described in Canadian media as a preacher, an activist and even a plumber.

There is no reference to photographs showing him sporting an automatic rifle appearing to lead a training camp for would-be terrorists. No one seems interested in videos where he makes possibly exaggerated claims taking responsibility for assassinating Mrs Gandhi, army chief Gen Arunkumar Vaidya, Punjab chief minister Beant Singh, MP Lalit Maken and others. And it revives memories of 1985, when terrorists based in Canada blew up an Air India Boeing 747 while it was on its way from Montreal to New Delhi via London. All 329 people on board were killed and the investigations, variously described as sloppy, a sham and a cover up, led to the conviction of just one person.

This unfortunate focus on a small group of extremists in Canada who happen to be Sikhs also does severe injustice to the overwhelming majority of the Sikh community that lives peacefully in countries around the world. Their creed of service before self was a shining beacon of hope to many depressed communities during the dark days of Covid-19.

Yes, Mr Nijjar was killed on June 14 in Surrey, British Columbia, by two armed assailants. They haven’t been identified, and the Toyota sedan in which they came hasn’t been traced. It isn’t clear at this point if Mr Nijjar was killed in an intra-Sikh gang war or by parties interested in maligning India.

Maybe the truth will come out in due course and maybe it won’t. But by impugning India in the Canadian Parliament, Mr Trudeau has allowed his domestic political imperatives to dictate his country’s foreign policy agenda and done enduring harm to relations between the two countries and to a community that deserves better.

This commentary originally appeared in The National News.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.