Nothing better demonstrates the churn in the Indo-Pacific as the manner in which Australia turned from being a close partner of China to an adversary, all within the space of four years.

Australia could become a major partner, but India must not only revive economic growth and revitalise trade policies, but also ensure social peace.

In 2014, the two countries agreed to a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’. Four years later, the relationship hit an iceberg. In some ways it was not too different from the Indian experience, though New Delhi never quite warmed up to Beijing as Canberra did. But the Wuhan and Chennai summits of 2018 and 2019 seemed to suggest that everything was going great, despite issues like Doklam, and then in 2020, the Chinese were all over eastern Ladakh.

A lot of what happened was the outcome of China’s changed behaviour — its assertiveness along its maritime edge with Japan and the South China Sea and on the landward side with India. This was accompanied by crackdowns in Xinjiang and then Hong Kong and the launch of its ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy.

All of this began to nudge both India and Australia closer to the United States, which had by 2017 realised that Beijing had been using Washington’s engagement policy to undermine American interests.

The signs of trouble were evident in Beijing when Canberra banned Huawei from its 5G network in 2018. Already concerns were being raised about the role of Chinese influence operations in Australian politics. But things went from bad to worse when Canberra joined the chorus for an investigation into the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. These actions were viewed by Beijing as part of the Trump administration’s attack on China.

By the end of 2020, China had systematically blocked a range of Australian exports — coal, barley, beef, copper ore, sugar, wine and timber. But for their part the Aussies doubled down, hitting at the influence operations, participating in the enhanced Quad meetings, tearing up the Victoria state’s BRI deals, and at the end of 2021, supporting the diplomatic boycott of the Winter Olympics.

In April 2021, Home Affairs Secretary Mike Pezzullo declared that ‘free nations’ were once again hearing ‘the drums of war’ in a prelude to Australia signing a new security alliance with the US and UK, called AUKUS, in September.

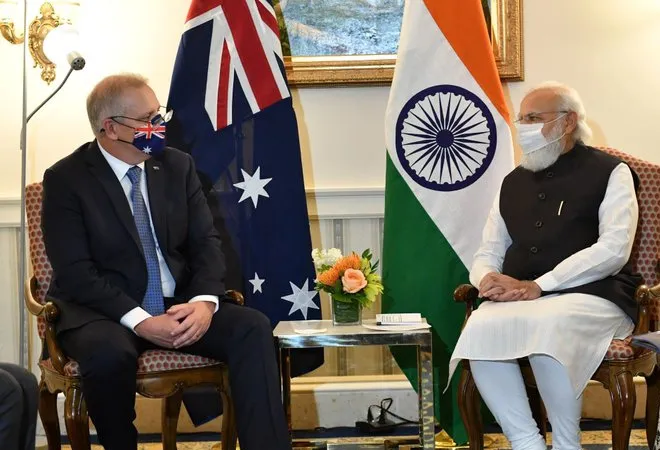

So, it is not a surprise that India and Australia have been looking at each other with greater interest in the past year. External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar’s visit to Australia last week marks a new phase in the relationship between the two countries.

The distance between Melbourne and New Delhi is almost the same as the one between New York and the capital. Australia is, indeed, far away and this distance is accentuated by the fact that it does not have the kind of salience that the US has on the Indian mind. Yet, Australia, though a country of just 25 million, is a rich country, with a 2021 nominal GDP of $1.6 trillion, almost as much as Russia.

Australia is, indeed, far away and this distance is accentuated by the fact that it does not have the kind of salience that the US has on the Indian mind.

People-to-people ties between India and Australia have been growing since the beginning of this millennium. Some 6,19,000 people said in the last census that they were of ethnic Indian background. Indians are migrating to Australia in large numbers and 1,15,000 students were studying there in 2020 before the Covid disruption.

As part of the general shift away from non-alignment of his mother and grandfather, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi had reached out to the region in 1986 through official visits to Australia and New Zealand. It was only 28 years later that Modi followed.

The Aussies, who also view themselves as an Indian Ocean power, had harboured suspicions of India in the 1980s and 1990s. A flashpoint came in the unduly harsh treatment meted out to India by Australia in the wake of the 1998 nuclear test. It took a long time for New Delhi to get over it. Many have not forgotten the Australian role in torpedoing the first Quad in 2008.

Blame it on Covid or coincidence, but 2020 was the year in which both Canberra and New Delhi began to get together finally after falling out with Beijing and even signed a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ agreement.

India and Australia are now on track to build durable relations. While one part of the security equation has been taken care of by AUKUS, the two can perhaps shape defence ties based on their common interests in the Indian Ocean Region.

The Quad leadership widened the remit of their organisation towards shared partnerships in areas like vaccine manufacture and distribution, climate change, critical and emerging technologies.

Simultaneously, they can focus on the opportunities offered by the Quad grouping. In their first-ever summit in March 2021, the Quad leadership widened the remit of their organisation towards shared partnerships in areas like vaccine manufacture and distribution, climate change, critical and emerging technologies. Quad has a long-term vision of promoting infrastructure and ‘quality’ development in the region, as well as creating ‘trusted and resilient supply chains’ away from China.

India and Australia will embed their strategic ties in the larger Quad engagement, which importantly includes Japan. Additionally, India stands to benefit from Australia and Japan’s deep networks and knowledge of the ASEAN region.

India-Australia annual two-way trade in goods and services is just about $18 billion, whereas Australia’s trade with China is in excess of $150 billion. Efforts are on to finally work out an FTA. With its resources like coal, iron ore, other minerals, agricultural products, education and skills training and healthcare, it could become a major partner in India’s growth story. But a lot of that presupposes India being able to get its act together, not only in terms of reviving its economic growth and revitalising its trade policies, but also ensuring social peace in an increasingly divided country.

This commentary originally appeared in The Tribune.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV