-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

This brief is part of ORF’s series, ‘Emerging themes in Indian foreign policy’. Find other research in the series here:

Gayathri Iyer, “As China Woos Nepal, Some Lessons for India”, ORF Issue Brief No. 274, January 2019, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

In 2016, the Nepal Pashmina Industries Association entered into an agreement with the Nepal Chapter of China’s Belt and Road International Trade and Investment Platform for the sale of large quantities of Nepali pashmina in China.[1] This trade development, seemingly small, has had strong implications for India.

First, it shows that countries looking for investments in the construction of transport infrastructure also look for guidance in quickly monetising physical connectivity. China is utilising this opportunity by connecting private traders with new markets in Asia. While India has had a long history of investments in overseas turnkey projects—some much ahead of Chinese investments overseas—it must now move beyond government-to-government transactions in such investments to integrate its neighbours’ private sector into its own expanded trade networks.

Second, South Asia is one of the least integrated regions in the world with “intra-regional trade accounting for only 5 percent of South Asia’s total trade and intra-regional investment smaller than 1 percent of overall investment.”[2] “Due to limited transport connectivity, onerous logistics and regulatory impediments, and lack of trust, it costs more to trade within South Asia than between South Asia and [the] world’s other regions.”[3] Given the right connectivity and impetus, small countries with unique products can be persuaded to reduce their traditional reliance on the western markets. While road connections between Nepal and China have existed for a long time, China is now utilising these connections to show Nepal that the Himalayas are not a trade barrier for rail-based trade with Asia and Europe, or even maritime trade through the South China Sea. China is providing economic alternatives for regional connectivity and many small countries such as Nepal are buying into the vision of ‘Community of Common Destiny’[4] amongst Asian players. This leaves the larger countries to deal with the regulatory, sustainability and debt risks that China brings.

Third, China is helping forge investment alliances in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in major global financial centres, including London and Hong Kong. Both countries are strong maritime trade hubs with a rich history of creating stable trade practices. The diversified base of funds helps China demonstrate to the BRI participants that, since the funds are not from China alone, the perceived threats of Chinese debt trap are without basis. As India itself stands at the crossroads of several grand alliances, it needs to show Nepal that such alliances offer the country newer and more stable investment opportunities.

Nepal’s example shows that China is finding it hard to turn itself away from the prospect of quickly monetising its investments in physical connectivity or improvements in border administration and ICT enablement. Nepal has welcomed China’s BRI along three tracks: the government-to-government track; the business-to-business track, including the private sector; and the knowledge-based approach to gain momentum and maximise benefits from assets.[5]

The regional multilateralism in Asia is such that each country fends for itself and cooperation takes place primarily in the bilateral field before it extends to multilateral platforms. This brief argues that India must use its strong bilateral relations with its neighbours to chart clear trade gains for each member from the BIMSTEC’s maritime engagements.

The question that must then be answered is this: Is India doing enough bilaterally to help Nepal take advantage of BIMSTEC’s maritime subregionalism?

Beyond Government-to-Government Investments

Till now, most of the funds for the BRI have come from within China’s own financial entity, the Silk Road Infrastructure Fund. The state-owned investment fund was primarily backed by China’s foreign-currency reserves. Much of the BRI—70 percent of the investments and 95 percent of the construction—is funded by Chinese financial institutions with state-owned enterprises (SOE) as executing bodies.[6] While it is difficult to calculate the economic returns to the investing SOE in hard numbers (average 20-year returns from 1995 to 2015 in the commercial real-estate slightly outperform the S&P 500 Index running at around 9.5 percent),[7] it is evident that China is starting to gain political influence in the invested countries.

The American Enterprise Institute reports that China has spent US$340 billion on the BRI from 2014 to 2017. Of this, construction accounted for US$202 billion, while investment in projects amounted to US$138 billion.[8] It is expected to continue constructing at US$60 billion per year and investing at an average annual rate of US$50 billion per year till 2023–24, after which China’s BRI spending may surpass US$1 trillion.[9] China is gathering momentum in helping forge investment alliances in major global financial centres across both the eastern and western hubs of the BRI. These alliances and funds can go a long way in allaying sustainability and security fears of the participating countries, including those of Nepal.

One such alliance is the London-based Green Belt and Road Investor Alliance (GBRIA) along the western end.[10] The GBRIA supports sustainable and investable projects along the Belt and Road. On the eastern end, Hong Kong assists in establishing offshore capital and financing vehicles from around the world.[11] The physical activities of the maritime industry in London have long migrated to other parts of the country due to London’s land-management and port-expansion challenges.[12] However, using its rich maritime history, the city has created one of the world’s most important maritime services centres, with an impressive cluster of high-value, desk-based activities in the form of ship brokerage, insurance, finance and arbitration services.[13] Hong Kong currently faces similar land-management and seaport-expansion challenges and is emulating London’s success in high-value desk services to leverage the BRI to its advantage.[14] Thus, both London and Hong Kong stand to benefit from financing and regulating the transcontinental BRI project, which is expected to connect over four billion people in more than 60 economies with the gross economic volume of several trillion.[15] If China helps Nepal overcome rail-route connectivity challenges through the Himalayas, Nepal could get access to new funds for trade with new economies.

India–Nepal Engagement in BIMSTEC

The Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) is “a sector-driven cooperative organisation, based on respect for the principles of sovereign equality, territorial integrity, political independence, non-interference in internal affairs, peaceful co-existence, and mutual benefit.”[16] BIMSTEC’s relevance hinges entirely upon its ability to make the maritime trade routes through the Bay of Bengal sustainable, regulated and balanced for its member countries. India must ensure that the Bay remains the more attractive and stable option for Nepal compared to the alternative maritime routes China has to offer.

While the BIMSTEC members cooperate on 14 priority sectors, India leads four: Counterterrorism and Transnational Crime; Telecommunication and Transport; Tourism and Environment; and Natural Disaster Management. None of these sectors directly make it incumbent upon India to prioritise trade opportunities for the private sector of the member countries.

India’s transactions with Nepal primarily remain at the level of government-to-government. The two countries launched the one-stop rail operation between Visakhapatnam container port terminal and the Birgunj Inland Container Depot in Nepal in 2017.[17] The seamless service involves all transit and customs clearance processes. The majority of freight being transported on this rail line is in the form of food products, garments and electronic goods that come from South Korea and China.[18] The Maersk shipping line opened a new commercial office in Kathmandu in June 2018, with a belief that the landlocked economy will now have an expanded maritime footprint through the Bay of Bengal. However, India may need to do more than simply enabling hard, physical connectivity to deepen Nepal’s financial integration with BIMSTEC and South East Asian countries beyond the Bay. Investing in telecommunication and transport may not be enough, and India must present new and fresh ideas as alternatives to Chinese-led trade assistance. BIMSTEC’s maritime connectivity advantages to Nepal must be chalked in a manner that allows its private sector to take advantage of newer and larger Indian and Asian markets to the South.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi was quick to engage with Nepal in 2014 and announce INR 100 billion line of credit for development projects, including the Upper Karnali and Arun III hydropower projects.[19] The Pancheshwar Multi-purpose Hydropower Project was restarted, which had been stagnant for 18 years. Talks on the first transcountry river-linking project—to bring surplus water from Nepal’s Sharda (Mahakali) river to the Yamuna river in Delhi—are currently underway.[20] However, most of these also remain government-to-government projects.

Cyril Cabanes, head of Asia Pacific infrastructure transactions at one of Canada’s pension-fund manager says, “It’s not just about putting capital in, it’s about generating returns and then moving on to the next opportunity, which India hasn’t quite graduated to.”[21] India has had a long history of investments in overseas turnkey projects, some much ahead of Chinese investments overseas, e.g. Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd (BHEL)’s investment in a massive power project in Tripoli, Libya in 1980.[22] However, it has yet to pave a road for trade innovation and people-to-people bond for mutual learning.

Less Balancing and More Positioning

The Center for Global Development evaluated the current and future debt levels of countries participating in BRI-funded projects and reported that 23 countries are at risk of debt distress.[23] .[24] It also pointed out that China’s track record of managing debt distress has been problematic. Unlike the world’s other leading government creditors, China has not signed on to a binding set of rules of the road.[25] However, the small countries, especially the ones that already have relatively weak governance, corrupt regimes and high dependence on debt instruments, remain largely ambivalent to such risks.[26] Such countries leave the task of resolving security, regulatory and debt default aspects of the BRI to the larger players, e.g. the US, India and Japan. The country chapters of China’s Belt and Road Investment platform are logging in into China’s confidence and acting as China’s agents to dovetail the private sector of the smaller countries into the BRI. Moreover, most of the 60-plus countries that have joined the initiative are amenable to BRI’s proposal to relocate China’s low-cost manufacturing to their own low-cost destinations.[27] For China, this is an opportunity to move up in the manufacturing value chain and bring a more spread-out development within its own territory, since most of its own development was largely concentrated around its southern coastal provinces.[28]

While major economies attempt to understand the challenges that arise from the complexity and unpredictability of China’s investments, the position of the US market is no longer clear. China has shifted the axis of cooperation and alignment for the US from the Atlantic to the Pacific: “President Donald Trump wants to take a firm relook at the global arrangements. He may renegotiate, even withdraw, from them where necessary. But before we paint the devil on Trump’s back, it’s important to recognise that China was the first to play the aggressive nationalism card in the global economic conversation. This feeds into Trump’s logic that Beijing wants to convert its wealth made from the existing trading system into China’s geopolitical advantage.”[29]

Meanwhile, India must not rest on its laurels and should instead learn from Nepal’s experience. Given the right connectivity and impetus, small countries with unique products can reduce their traditional reliance on the western markets to work with lucrative Asian ones. For China, the advantage lies in positioning itself as a game changer. It demonstrates confidence in contesting the Westphalian model of international relations to create a vision of “community of common destiny” amongst Asian players.

Currently, Nepal uses the Indian ports of Kolkata and Vishakhapatnam mostly through the Raxaul–Birgunj border crossing to conduct trade with third countries through the Bay of Bengal. India is Nepal’s largest trading partner, accounting for almost 65 percent of Nepal’s total trade. Nepal exports nearly 57 percent of its total to India and imports almost 65.5 percent of merchandise goods from India.[30]

However, a series of events in recent years has led to Nepal turning to China to reduce its heavy dependence on India for facilitating trade. In 2015, following the Nepal earthquake, a four-month-long truck blockade by India at the India–Nepal border created a huge fuel and essential-goods crisis in Nepal.[31] This was India’s response to Nepal’s lack of adequate inclusion of Madhesis in its Constitution. Madhesis, the Indian-origin inhabitants of the Terai region in Nepal, opposed the splitting of Nepal into seven provinces.[32] The issues were further exacerbated by the longstanding logistical problems that Nepal—as a landlocked nation—has had with India. “The cost of cargo between Kolkata and Kathmandu is three times compared to the cost of cargo between Hamburg in Germany and Kolkata. In addition to that, traders also face customs trouble at the Indian ports.”[33] Therefore, to stop Nepal from completely shifting allegiance to China, India must work hard to help Nepal’s private sector use India’s own markets or trade relations with littoral states along the Indian Ocean Rim, where India conducts 40 percent of its trade.

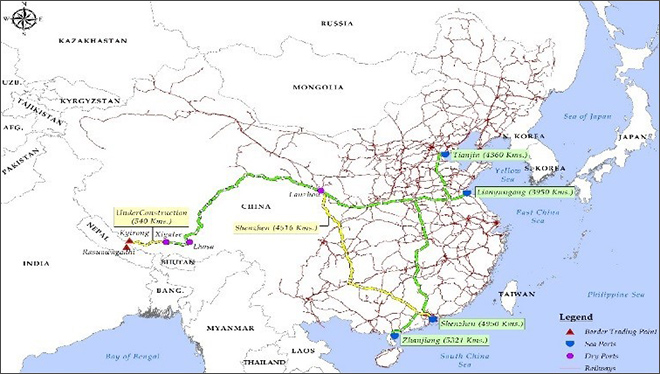

China has already granted Nepal access to its ports of Tianjin, Shenzhen, Lianyungang and Zhanjiang, opening alternate maritime routes for the landlocked nation.[34] It is further challenging India’s longstanding position as the main outside power, by aligning infrastructure projects for better access into Nepal with aid and investment. For China, Nepal is an advantageous regional partner, in not only expanding business but also addressing China’s security concerns in the Tibetan region.[35]

India can no longer assume that the Himalayas offer a natural barrier between Nepal and China. S. Jaishankar, former foreign secretary of India, puts a premium on agility, non-reciprocal arrangements in generous investments and a non-traditional attitude to play the global game: “The rise of China has fundamentally changed the global calculus. Expectations, opportunities and challenges in our neighbourhood require greater Indian initiative. The name of the game is less of balancing and more positioning. This is not just an issue of intent, it’s also one of delivery.”[36]

The Modi government is increasing engagements with its neighbours. While India may not be able to match BRI’s scale and scope, it must use its trust-based historical relationships with the neighbours to tackle the BRI through sustainable, albeit smaller, engagements. India must look beyond investing capital into the BIMSTEC countries’ connectivity and should help generate returns for them from their hard assets. China has forged strong bilateral ties with Nepal to woo it away from its dependency on the Bay of Bengal by allowing it to use the ports of Tianjin, Shenzhen, Lianyungang and Zhanjiang.

Investment Alliances for Diverse Choices

Various extended maritime and overland connectivity engagements of India with Africa, Russia, the Pacific nations and South Asian nations have left Nepal out of discussions.

The Indo-Japanese Africa Asia Growth Corridor (AAGC), for example, aims to enhance quality infrastructure, institutional connectivity, people-to-people partnership, capacity enhancement and skills development projects, mainly through sea-based connectivity, in contrast to China’s sea- and land-based BRI.[37] While South Asia’s connectivity with East Africa is at the heart of this programme, India has failed to integrate its BIMSTEC partners into the programme, either because it has not had a consistent neighbour-management framework since Independence or because most of the efforts to address regional connectivity have been bilateral or trilateral.[38]

The Indo-Pacific quad, a strategic partnership between like-minded nations—the US, Japan, Australia and India—aims to promote a “rules-based” order in the Indo-Pacific with a baseline level of predictability and reasonable principles of behaviour. The quad lays emphasis on greater cooperation in weapons-supply, intelligence-sharing, diplomatic pressure, and posturing.[39] However, since it does not project itself as a response to the BRI, India has not been able to spell the Quad’s strategic value as an investment and connectivity opportunity to its immediate neighbours, including landlocked Nepal.

Meanwhile, the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) is a multimodal transportation corridor spearheaded by Iran, Russia and India for the purpose of promoting transportation cooperation among the member states.[40] It connects the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea via the Islamic Republic of Iran to St. Petersburg and northern Europe via the Russian Federation.[41] Nepal can be integrated into the INSTC through ports in Gujarat and Maharashtra, giving it better access to Russian, European and Central Asian markets.[42] Moreover, some of the world’s fastest-growing economies, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, seek alliances with India as an alternative to the rising Chinese influence and an unpredictable US, which Nepal can use to its advantage.[43]

Provided that India is able to give Nepal a structured solution to resolve overland transit and logistical issues, these partnerships and associations could make India the better option for Nepal as a trading and transit partner. However, continuity and execution of infrastructure projects remain challenges for India.

Conclusion

Despite technological advancements in areas such as transport and connectivity, Nepal and other landlocked developing countries continue to face structural challenges in accessing global markets. Distance from the coast and their dependence on neighbours for transit infrastructure, weak and problematic administrative practices, and lack of peace and stability are some of the reasons why these countries lag behind their maritime neighbours in trade and development.[44]

However, the fact that distance is no longer a consideration for Nepal when it comes to choosing access to the sea via Chinese seaports should be a wake-up call for India. While the idea of reviving BIMSTEC is promising, the process of integrating all partners equally and meaningfully into the larger Indian Ocean Region has failed in execution due to challenges related to overland connectivity. Regional multilateralism in Asia has shown that each country fends for itself and cooperation takes place primarily at the bilateral level before it extends to multilateral platforms. India has the opportunity to use BIMSTEC to play a vital role in integrating member countries with the world, through trade, economic, digital and people-to-people connectivity.

[1] Xinhua, “Nepal set to promote pashmina products in China via Belt and Road platform”, ChinaDaily.com.cn, 26 March 2017.

[2] “One South Asia”, The World Bank, .

[3] Ibid.

[4] Jacob Mardell, “The ‘Community of Common Destiny’ in Xi Jinping’s New Era”, The Diplomat, 25 October 2017.

[5] ANI, “Chinese Belt and Road Initiative will pave new opportunities for Nepal”, Indian Express, 13 February 2018.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Cecilia Joy-Pérez and Derek Scissors, “The Chinese State Funds Belt and Road but Does Not Have Trillions To Spare”, American Enterprise Institute, March 2018.

[9] Ibid.

“B&R News: Chinese SOEs accelerate participation in B&R construction”, Silk Road Chamber of International Commerce, 9 August 2018.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Hong Kong Maritime Services Cluster: Meeting the Challenges”, Hong Kong Trade Development Council, 2 February 2016.

[13] “Foundering, Maritime Industries”, The Economist, 25 September 2015.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Chinese Belt and Road Initiative will pave new opportunities for Nepal”, Indian Express, 13 February, 2018.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Anirban Chowdhury, “Maersk Line India aims to expand supply chain solutions”, The Economic Times, 18 September 2017.

[19] PTI, “Modi announces $1 billion concessional line of credit to Nepal”, Times of India, 3 August 2014.

[20] Toufiq Rashid, “India looks to Nepal to revive Yamuna river”, Hindustan Times, 22 March 2018.

[21] Matthew Burgess and Alyssa McDonald, “Look to India for Returns, Not China’s Belt-and-Road, Funds Say”, Bloomberg, 16 May 2018.

[22] Huma Siddiqui, “NTPC, BHEL look to expand presence in Africa”, Financial Express, 17 October 2015.

[23]John Hurley, Scott Morris and Gailyn Portelance, “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective”, Center for Global Development, March 2018.

[24]John Hurley, Scott Morris and Gailyn Portelance, “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective”, Center for Global Development, March 2018.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Matthias Lomas, “Which Asian Country Will Replace China as the ‘World’s Factory’?” The Diplomat, 18 February 2017.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Pranab Dhal Samanta, “Why India needs to shed ambivalence in this changing world order”, The Economic Times, 3 July 2018.

[30] Meeting of Nepal-India Inter-Governmental Committee (IGC) on Trade, Transit and Cooperation to Control Unauthorised Trade held at Kathmandu on 26–27 April 2018, Ministry of Commerce, Government of Nepal.

[31] “UN concerned as India-Nepal border issues hit supplies for earthquake victims”, The Economic Times, 25 October 2015.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Deepak Adhikari, “Nepal gets access to China ports, analysts say it’s a ‘huge deal’”, 19 September 2018.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] S. Jaishankar, “Disruption in world order: The nimblest power with least problems will fare best”, The Economic Times, 13 August 2018.

[37] “Africa Asia Growth Corridor”, About AAGC.

[38] Ibid.

[39] “Quad needs both economic & military plan for Indo-Pacific”, The Economic Times, 23 February 2018.

[40] International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC).

[41] Ibid.

[42] P. Stobdan, “India Gears Up to Enter the Eurasian Integration Path”, Institute for Defense Studies and Analysis, 7 June 2017.

[43] Nyshka Chandran, “Southeast Asia is increasingly turning to India instead of the US or China”, CNBC, 16 March 2018.

[44] Michael L. Faye, John W. McArthur, Jeffrey D. Sachs and Thomas Snow, “The Challenges Facing Landlocked Developing Countries,” Journal of Human Development 5, no. 1 (22 January 2007): 31–68, DOI: 10.1080/14649880310001660201.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Gayathri Iyer was a Junior Fellow works with the ORF Maritime Policy Initiative. She tracks ocean governance policies and international maritime trade sustainability for global ...

Read More +