Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 includes two different indicators, ‘2.1: by 2030 end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round; SDG 2.2: By 2030, end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving, by 2025, the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under five years of age, and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women, and older persons.’ With more than 600 million people projected to face hunger by 2030, 1 in 3 people facing moderate to severe food insecurity based on the food insecurity experience scale, and about 3 billion people unable to afford a healthy diet, the world is off-track for reaching the zero-hunger goal by 2030.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation report estimates that about 3 billion people globally lack sufficient income to purchase the least-cost form of healthy diets recommended by national governments. The majority of these reside in Southern Asia (1.3 billion) and sub-Saharan Africa (829 million), with high numbers also in South-eastern Asia (326 million) and Eastern Asia (230 million). According to current estimates, more than one-third of the world's population will still be unable to pay the expense of decent food by 2030, and three-quarters of Africans will still be suffering from hidden hunger. These estimates are based on baseline assumptions.

The triple whammy of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ukraine-Russia war, and frequent natural disasters have made the food security system in South Asia more vulnerable while increasing the prevalence of undernourishment in the region including India. There has been a rise in hunger from 12 to 17 percent since 2018-2021, with varying prevalence among South Asian countries, with the highest in Afghanistan at 30 percent to the lowest at 4 percent in Sri Lanka. Of the 768 million people undernourished globally in 2021, more than half (425 million) were in Asia, with more than 330 million living in Southern Asia. The number of undernourished has risen from 307.6 to 331.6 million from 2020 to 2021 respectively. Accounting for about one-third of the world’s poor and food-deprived population and burdened with substantial gaps across almost all socio-economic indicators of sustainable development, the subregion’s progress is, therefore, a key determinant of the extent of global SDG achievements.

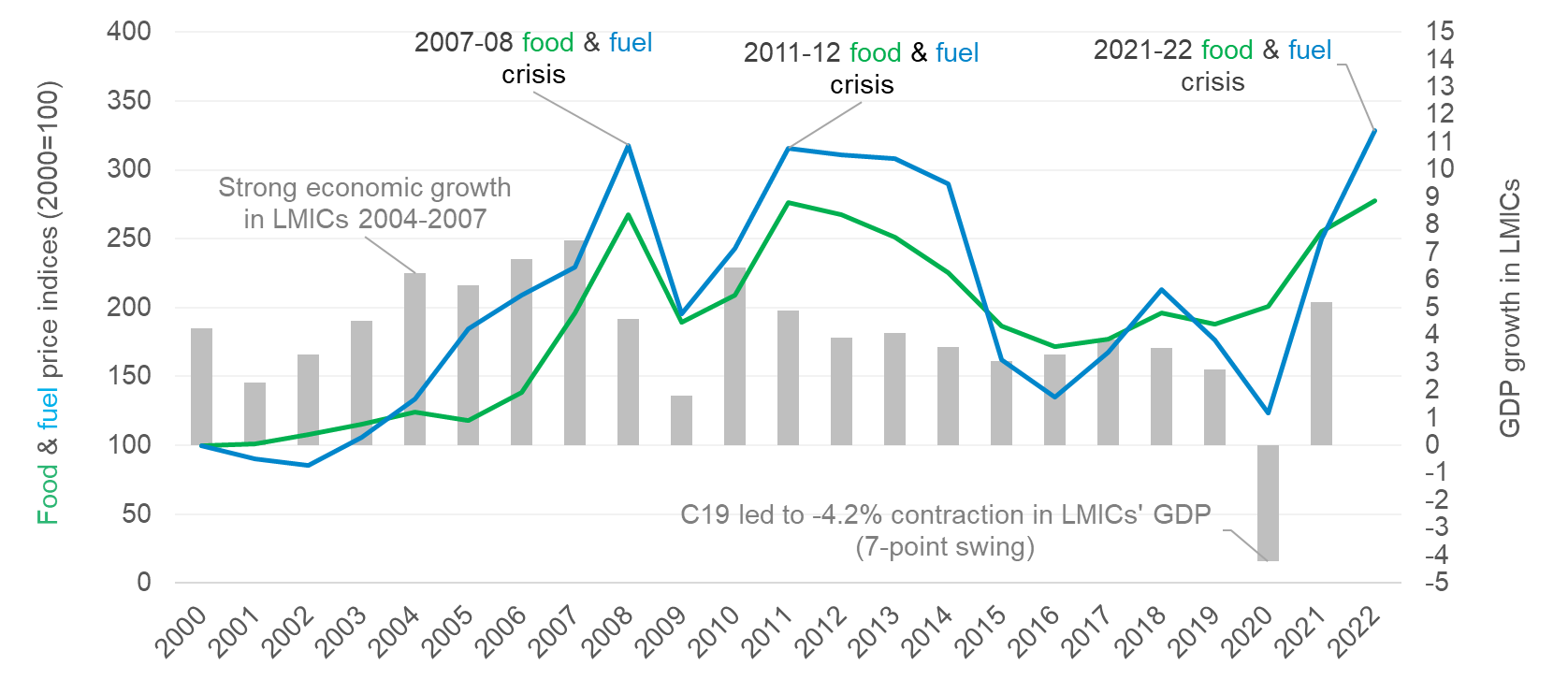

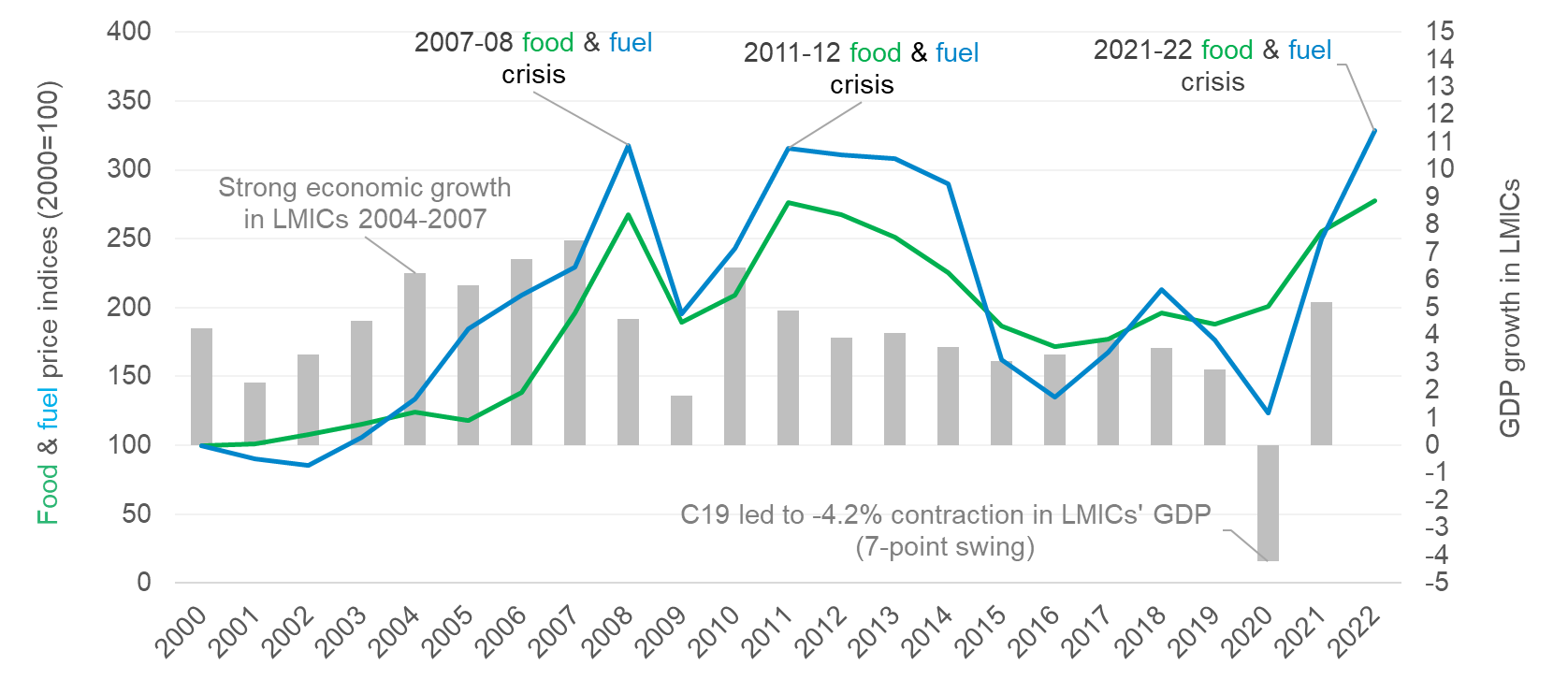

The figure below indicates the uneven economic growth in lower-middle-income countries since the end of the first decade of the millennium, with particularly large growth slowdowns in many poorer countries and regions. This macroeconomic environment has also been marked by significant volatility. Over the past 15 years, there have been three food and fuel crises (2007–08, 2010–11, and 2021–22), marked by substantial increases in the price of food and agricultural inputs on both the local and foreign markets. The COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in sharp drops in income and restricted access to food for many poor households worldwide in 2020, was the catalyst for the most current food crisis.

Since 2015, when the SDGs were announced, there have been several calls for action to address  the food and diet crisis. Also, the commitments to actions have been made by governments in the high-income as well as low- and middle-income countries to address food security. However, at the mid-point of the 2030 SDG Agenda, it is not very clear as to which of these commitments is best fit for the purpose and also fit for the future.

the food and diet crisis. Also, the commitments to actions have been made by governments in the high-income as well as low- and middle-income countries to address food security. However, at the mid-point of the 2030 SDG Agenda, it is not very clear as to which of these commitments is best fit for the purpose and also fit for the future.

Against this backdrop, the existing commitments were analysed to examine which are most important to focus on given the current challenges and also the anticipated future scenarios that could shape the global action at this critical juncture. In light of the above, the Observer Research Foundation in collaboration with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) South Asia organised a regional consultation on ‘Analysing Global Commitments on Food Security and Diets: Implications for South Asian Countries’ on 2 February 2024. This discussion was attended by 50 participants such as government officials, academics, development partners, international organisations members, and members of civil society from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. It sought to draw learnings from the experience of other nations to help us shape the final recommendations and also support the development of advocacy around SDG 2.

Findings of the analysis

The analysis of 107 intergovernmental declarations stemming from nine global fora seeking to address hunger, food insecurity, and healthy diets found that stated intentions to solve the global food security and hunger challenges have become more pronounced at global meetings over time, especially amidst a polycrisis. At the same time, we find that the intent to act is not consistently matched by commitments to specific actions that could help accelerate reductions in hunger. A lot of commitment statements are unclear on what policy interventions should be increased in scope for SDG 2 action or how to improve the capacity of various stakeholders to carry them out. While horizontal coherence was mentioned across the majority of global fora, it was only present in approximately half of the commitment statements, with even less recognition of the necessity for vertical coherence from global to local levels. Furthermore, while raising funding is frequently acknowledged as being necessary to achieve SDG2, few commitments made in international forums provide information on the precise amount of funding required. Despite global efforts that convey the importance of accountability and monitoring, usually by way of progress reports, we find few consequences for governments that do not act on commitments made in global fora.

Key takeaways from the discussion

- A robust social protection system is essential for enhancing child nutrition outcomes.

- In the comprehensive agenda encompassing climate finance and social protection, a pivotal component is nutrition-sensitive social protection, underscoring its crucial role in addressing nutritional challenges within communities.

- Scale-up strategies are often overlooked, and there is a notable lack of emphasis on capacity strengthening within discussions.

- While strong findings have been established, there is a need for specific sub-activities tailored to the region. We eagerly anticipate learning about the precise details of these actions to disseminate them to country-level decision-makers, particularly those participating in WTO and other relevant working groups, with a specific focus on nutrition-related matters.

- Understanding hunger within the context of SDG2 has become increasingly complex due to its intersection with climate change. It's imperative to gain clarity on how to proceed with the joint agenda addressing hunger and climate change. Previously, the focus was on support flows from high-income countries to low- and middle-income countries, but now we recognise resource challenges even in high-income countries. There's a need to draw lessons from climate financing, where estimations are abundant to address climate change requirements. Given the inherent relationship between SDG2 and climate change, it is essential to ensure that resources are directed not only towards addressing climate change but also towards promoting food security and nutrition.

- Civil society should strategise on enhancing their preparation for participation in global events. This could involve planning the creation of collaterals, supporting relevant movements, and organising participation strategies leading up to these events. Collaborating with ideal partners is crucial to contribute effectively to shaping the overarching narrative.

- To initiate action on commitment areas, we can begin by anchoring declarations with explicit commitments. Traditionally, COP discussions have not centred on food systems, yet when climate and food security/nutrition intersect, a unique perspective emerges. Bridging COPs together requires a concerted effort to understand the interconnectedness and identify shared priorities, fostering collaboration across sectors for effective action.

- We seem to be overlooking the critical issue of corruption. The recent Corruption Perception Index Report by Transparency International for 2023 reveals a concerning trend: except for Bhutan in South Asia, all member states have experienced a decline. While there's discussion about securing fresh funds and new financing, the effective utilization of existing resources remains problematic. It's imperative to address internal fund utilisation and optimise existing resources before seeking external or additional funding.

- Need for advocating for increased investment in this area as a crucial step towards effectively addressing hunger. Investing in infrastructure such as irrigation systems and cold storage facilities can significantly mitigate the challenges posed by unpredictable weather patterns.

- Overconsumption and wastage present significant issues amongst the rich, while the poor communities suffer. The global community must intervene in addressing this issue effectively.

- Promoting dietary diversity is crucial, and alongside, we must also encourage the cultivation and consumption of traditional Himalayan crops, which are rich in nutrients and contribute to a balanced diet.

- Community-based initiatives such as cooperatives play a vital role in fostering collective actions and resource sharing, thereby strengthening resilience against food insecurity. Additionally, promoting ecotourism can provide an alternative source of income for people in these communities.

- Common issues in the region include production, supply chain, market challenges, and soil health degradation. Moreover, the region has recently faced three consecutive shocks. It is essential to identify and disseminate good practices while learning valuable lessons on data sharing, information exchange, innovation, and optimising the use of climate financing to foster a systemic approach towards addressing these challenges.

- Due to climate change, promoting smart agriculture is imperative, especially where conventional farmers lack the capacity and capability. In this context, private investment and engagement are crucial, but it must not disregard conventional farmers. Therefore, an interactive governance mechanism is essential to ensure inclusivity and sustainability in agricultural development.

- Given that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) encompass a broad spectrum of interconnected objectives across economic, social, and environmental dimensions, the challenges of coordination and integration loom large. Progress toward these goals demands seamless collaboration among governments, businesses, civil society, and international organizations.

- The global community must prioritize increasing food availability and addressing the impact of inflation on food prices. Additionally, efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change are essential in ensuring food security for all.

- When considering accountability, allocative efficiency and utilisation efficiency are equally significant, alongside the allocation of new resources. Moreover, countries in South Asia have the potential to collaborate as a union, not only in terms of food production but also in the sharing of food through market mechanisms.

- Ensuring the transformation of policies into actionable practices at the ground level should be a paramount commitment area.

- Another essential commitment area could involve placing a special focus on reaching out to the most marginalized communities within the scope of universal coverage, addressing strategies, financing, and ensuring accountability measures are in place.

- It is imperative to establish a robust system or mechanism that ensures the uninterrupted flow of food from production to consumption, is resilient to potential crises and disasters that may occur periodically.

- We need to formulate a short-term strategy involving targeted social protection for those experiencing undernourishment, and a medium-term plan addressing issues related to prices, distribution, and nutrition security, while also prioritising sustainable agriculture to meet future demands.

- Food security should be integrated into all policy discussions, as it is essential for holistic development. This should encompass leveraging CSR funds in India towards initiatives promoting access to healthy diets, supporting local food production, and raising awareness about nutritious foods and healthy dietary practices, while also highlighting the importance of addressing non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

- Climate financing requires a greater emphasis on adaptation measures, alongside mitigation efforts, underscoring the crucial role of global funding agencies in facilitating this shift. Additionally, promoting crop diversification plays a pivotal role in addressing issues related to hunger, nutrition, and water security in the face of climate change.

- The disproportionate allocation of funds towards climate mitigation, with only a fraction dedicated to adaptation, poses a challenge for promoting climate-resilient agriculture, particularly in regions like the Global South where adaptation funds are crucial for addressing food security issues. There is an urgent need for a more balanced allocation that prioritises adaptation efforts to effectively tackle the challenges posed by climate change in agriculture.

This event report was written by Shoba Suri, Senior Fellow, Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

the food and diet crisis. Also, the commitments to actions have been made by governments in the high-income as well as low- and middle-income countries to address food security. However, at the mid-point of the 2030 SDG Agenda, it is not very clear as to which of these commitments is best fit for the purpose and also fit for the future.

the food and diet crisis. Also, the commitments to actions have been made by governments in the high-income as well as low- and middle-income countries to address food security. However, at the mid-point of the 2030 SDG Agenda, it is not very clear as to which of these commitments is best fit for the purpose and also fit for the future.