Introduction

Their remote locations, limited land area, and minimal human and capital resources make small island developing states (SIDS) highly vulnerable to the adverse impacts of climate change,[2] such as rising sea levels that threaten their existence and extreme weather events (for instance, hurricanes and cyclones) that can cause widespread destruction, loss of life and property, and economic setbacks.[3] Climate change also often affects SIDS’ water resources, agricultural output, and fisheries, directly impacting their food security, sustainable development, and economic agendas. Notably, climate change also impacts SIDS’ indigenous livelihoods, cultural heritage, and practices, causing economic marginalisation, discrimination, and unemployment.[4]

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated an already precarious situation for most SIDS, widely affecting society (particularly health) and the economy, and amplifying existing sustainability challenges.[5] It also slowed the effects of climate change adaptation and mitigation in the SIDS and elsewhere,[6] forcing the SIDS that had been pursuing climate-resilient strategies to divert already-scarce financial resources to support socioeconomic initiatives undertaken to combat the pandemic.[7] The United Nations notes that carbon emissions around the world are returning to pre-pandemic levels, and greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations are now at record-high levels.[8] Notably, SIDS are responsible for just under 1 percent of these GHG emissions.[9]

Given the challenges posed by their limited land area, small population sizes, reliance on natural resources, and the high vulnerability of their fragile ecosystems, SIDS have turned to their large ocean territory to attempt to control the adverse effects of a changing climate through the blue economy framework.

Pioneered by economist Gunter Pauli, the blue economy concept is rooted in the sustainable development of the ocean and seeks to balance social equity, economic growth, and environmental conservation.[10] Although SIDS have lower emissions levels than more developed countries, they are disproportionately impacted by climate change. As such, the blue economy model seeks to offer these countries a framework for sustainable development. The model relies on a commitment to the sustainable use of ocean resources, such as sustainable fisheries (for example, a reduction of bycatch and increased science-based fisheries management) and responsible aquaculture (essentially, preserving marine biodiversity while ensuring a continuous food supply).[11] The blue economy model can help chart a development pathway for a resilient and prosperous future for SIDS based on the principles of conservation and social equity. As such, it aligns with most of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those related to poverty (SDG-1), food security (SDG-2), gender equality (SDG-5), energy (SDG-7), decent work (SDG-8), climate action (SDG-13), and life below water (SDG-14).[12]

As of February 2024, several countries, including some SIDS, have integrated blue economy principles into their development strategies.[a] For example, India and Seychelles—which have vastly diverse geographies, economies, and population sizes—have recognised the significance of their ocean space in driving economic growth, ensuring food security, and mitigating climate change.[13],[14] In these countries, the blue economy strategy is focused on sustainable fisheries management, harnessing renewable energy, leveraging marine biotechnology, promoting responsible aquaculture, and developing sustainable tourism.[15] As such, the blue economy model can help SIDS and other coastal countries address climate change by promoting a sustainable and climate-neutral economy.

Climate Change Financing: A Persistent Challenge

Although promoting the blue economy is increasingly crucial for the sustainable development of SIDS, blue financing remains a significant challenge for these countries. Most SIDS struggle to secure adequate climate financing to implement mitigation, adaptation, or resilient strategies because their unique geographical and environmental characteristics often necessitate higher implementation costs.[16]

Climate finance refers to international or local financing measures that seek to support climate change mitigation or adaptation actions. Several facilities exist to provide such financing to countries that are facing the impacts of climate change. For instance, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) has operated as a financial mechanism since 1994, and it manages two special funds, the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF) and the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), which were created to provide additional funding for SIDS and LDCs; the Green Climate Fund (GCF) came into existence under the Paris Agreement to channel finance to developing countries and is the world’s largest international fund dedicated to supporting climate action in developing countries;[17] and the Adaptation Fund (AF) was created under the Kyoto Protocol in 2001 to provide financing to countries impacted by climate change.[18] Additionally, several multilateral and regional development banks and bilateral donors, such as the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and Climate Action, provide climate financing.[19]

While the emergence of such funds since the early 1990s should have alleviated climate financing issues, it has remained a persistent challenge for developing countries and SIDS. A 2022 report by the United Nations Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States noted that the current financing systems fail to consider SIDS’ unique needs and vulnerabilities, resulting in fewer funding options for these countries.[20] SIDS’ access to such finance is also impacted by bureaucratic hurdles, complex application processes, high transaction costs, small project sizes, and data limitations for adaptation projects.[21] Some SIDS—such as Aruba, Barbados, Puerto Rico, and Seychelles—tend to be ineligible for concessional financing due to their classification as high- or middle-income countries despite their severe climate, capacity, and structural challenges.[22] However, all SIDS face a looming debt crisis, as their vulnerability to climate change increases the cost of borrowing to finance much-needed long-term investments.[23]

According to the United Nations, the annual cost for SIDS to adapt to climate change is estimated to be between US$22 billion and US$26 billion.[24] As such, a critical financing challenge for most SIDS is differentiating between what is considered to be climate finance for adaptation projects and what is for investments in their development agenda independent of climate impacts. The lack of clear guidelines and methodologies to define these issues and estimate the benefits of climate financing puts SIDS at an inherent disadvantage.[25]

Alternative Blue Financing Mechanisms

Given the challenge of raising financing through the existing systems, SIDS are now adopting alternative and innovative financing mechanisms, including blended financing.[26] Some of these mechanisms, and associated case studies reflecting their use and impact, are discussed below:

Blue bonds allow SIDS to raise funds for environmentally sustainable and ocean-related projects. The funding can then be allocated towards supporting fisheries, marine conservation, renewable energy, and other sustainable blue economy sectors. These bonds attract socially responsible investors and provide a dedicated funding source for blue economy projects.

However, such bonds also have some disadvantages. The lack of a standardised framework for green and blue bonds can lead to challenges defining which activities qualify as environmentally sustainable. The bonds also have a limited market size and appetite. Additionally, robust monitoring and reporting are required to ensure that the funds from these bonds are used for their intended purposes.[27]

Nonetheless, blue bonds have gained increasing attention in recent years for successfully supporting the transition of marine protected areas, through initiatives such as marine spatial planning, coral reef restoration, and fisheries and tourism management.[28] Currently, blue bonds are funding conservation trusts in Belize, Ecuador, and the Seychelles.[29]

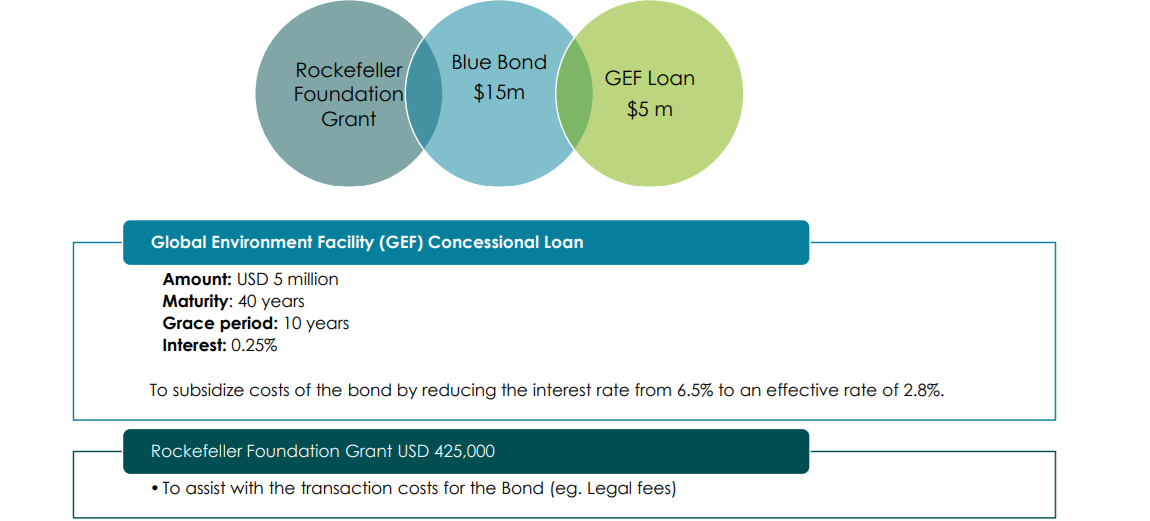

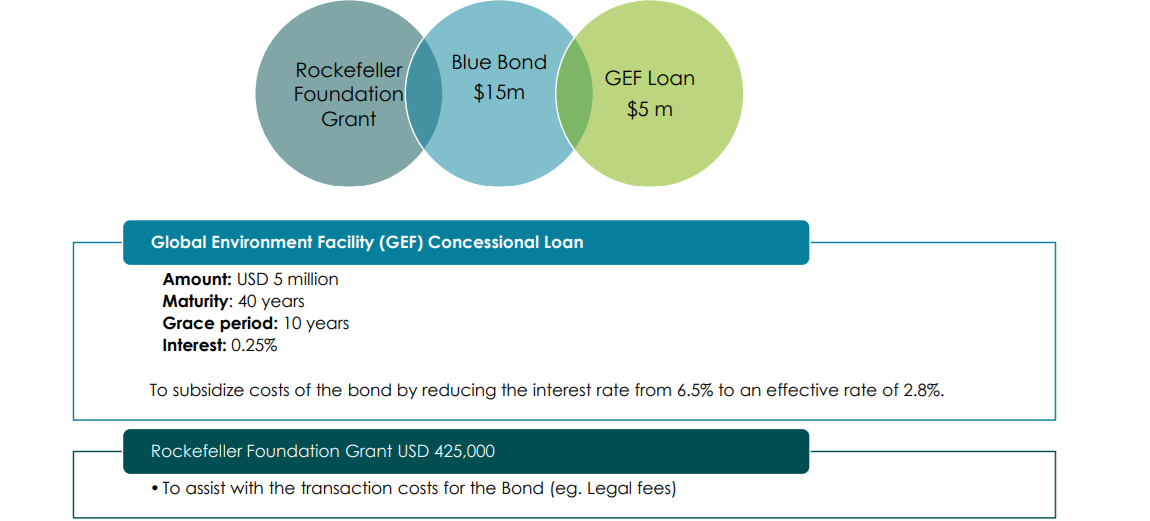

The Seychelles was the first country in the world to launch a blue bond, amounting to US$15 million (see Figure 1). The bond was partially guaranteed by the World Bank by a sum of US$5 million and further subsidised by the GEF with a US$5 million concessional loan.[30] The proceeds of the blue bond are administered by two bodies: US$3 million from the Seychelles’ Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust (SeyCCAT) is used to provide grants, and US$12 million from the Development Bank of Seychelles is used to provide loans.[31] The Rockefeller Foundation was also involved as a donor, granting US$425,000 to assist with the transaction costs for the bond.

Six other countries (Belize, Fiji, Palau, Portugal, Barbados, and Indonesia) have adopted similar bonds.[32]

Figure 1: The Structure of Seychelles’ Blue Bond

Source: Blue Bond: The Seychelles Experience[33]

This is a debt instrument that involves purchasing a developing country’s debt at a discounted rate and cancelling the debt in return for environment-related action. Debt-for-nature swaps are beneficial when the debt amounts are marginal. However, research has shown that debt swaps alone may not counter climate change or generate new capital; therefore, needs covered by sovereign debt must still be addressed.[34] Nonetheless, the instrument has been promoted to generate greater awareness among policymakers on accelerating environmental degradation.[35]

In 2015, the Seychelles closed its first debt-for-nature swap. This finance swap, also known as the ‘dolphins for dollars deal’, now funnels a stream of the country’s repayments into the SeyCCAT trust to invest in schemes contributing to its blue economy strategy.[36] In 2020, a third of Seychelles’ ocean territory was effectively declared a marine protected area. This was the result of the Seychelles Marine Spatial Plan, which was an output of the debt-for-nature swap.[37] Seychelles has thus exceeded its commitment to protect 10 percent of its exclusive economic zone under SDG-14.5 (by 2020, conserve at least 10 percent of coastal and marine areas, consistent with national and international law and based on the best available scientific information).[38]

In 2023, the International Institute for Environment and Development noted that the world’s most climate-threatened countries spent billions more to pay their debts than they received to tackle climate change.[39] Private-sector investors have been providing blue sector companies (sectors relating to aquaculture, renewable energy, ports and shipping, and sustainable fisheries), and entrepreneurs with impact investments for their blue economy strategy and contributing capital towards projects with social and environmental impacts.[40] Impact investments mobilise private-sector funding and expertise towards development finance that may be lacking through public-sector mechanisms, often aligning these investments to meet the SDGs.[41]

Several impact investment funds have gained attention in recent years, including the Sustainable Ocean Fund, which focuses on marine-related industries; the Ocean Assets Fund, which invests in companies working to use ocean resources sustainably; and the Blue Ocean Partners investment firm, which invests in companies working on the blue economy strategy.

Other forms of financing for the blue economy framework include public-private partnerships, which can involve joint investments, risk-sharing, and long-term commitments. Additionally, oceans and fisheries insurance provide financial protection against risks such as natural disasters, overfishing, and climate change impacts.[42] SIDS can also explore opportunities to generate carbon credits through blue carbon projects, as seen through conserving mangroves and seagrass meadows. While the blue carbon offset market remains nascent, these credits could potentially be sold to climate-conscious entities seeking to offset their carbon emissions. The Blue Peace Financing Initiative launched by the United Nations and the Swiss Agency for Development also indicates the changing landscape of blue financing.[43] For instance, the initiative proposes to transform global perceptions around water from a conflict-based resource into a peaceful instrument for multisectoral investment and promote access to capital for non-sovereign entities.[44]

To effectively promote the blue economy strategy in SIDS, a combination of these financial instruments, tailored to the specific needs and circumstances of each country, may be necessary. Additionally, enhancing financial literacy, governance structures, and regulatory frameworks can create an enabling environment for successful implementation.

Conclusion

International collaborations and national-level linkages will be crucial for SIDS to finance their blue economy agenda in a post-pandemic era. Notably, COP28 was viewed as a potential catalyst for global action that could support SIDS’ blue economy strategies by mobilising resources, fostering partnerships, and raising investments in fisheries, marine conservation, and resilience projects.

In December 2023, the United Arab Emirates pledged US$30 billion to a new fund to invest in climate-friendly projects worldwide, with US$5 billion earmarked for the Global South.[45] This followed the announcement at COP28 that the Loss and Damage Fund, a long-sought fund to help economically weaker countries deal with climate change, had received over US$726 million in contributions.[46] However, this pledge is equivalent to less than 0.2 percent of the irreversible economic and non-economic losses that developing countries face from global warming each year.[47] Additionally, pledges have fallen short of what is needed, with some estimates for the loss and damage incurred in developing countries from climate change thought to be greater than US$400 billion a year.[48]

The GCF also received pledges of US$3.5 billion at COP28. This might help the fund establish a dedicated envelope for SIDS within its Enhanced Direct Access pilot, a programme that seeks to channel more immediate climate funding to developing countries.[49] This recommendation comes from the need for a dedicated financing mechanism for SIDS and may present a solution that will also serve to facilitate access by building robust regional and country systems and strengthening institutional capacity.

Still, SIDS are confronting the fallouts from climate change, which is testing their economic and social resilience.[50] Notably, the theme for the upcoming Fourth International Conference on Small Island Developing States (scheduled to be held in May in Antigua and Barbuda) is ‘charting the course toward resilient prosperity’. The SIDS are expected to collaborate to form a robust negotiation group to advance their joint interests by calling for an urgent and clear way forward. Despite ambitious nationally determined contributions, SIDS recognise that international collaboration on climate change financing will continue to be the cornerstone for resilience building. To that end, a more substantial and accessible framework that integrates the principles of international collaboration and efficient fund utilisation is required for SIDS to withstand climate impacts.

This report is published under the SUFIP Development Network. The SUFIP network is a joint collaboration between the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) and the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) aimed at fostering cooperation and knowledge exchange for strengthening responses to developmental challenges in the Indo-Pacific.

Endnotes

[a] These countries include Australia, Bangladesh, Belize, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Denmark, Fiji, France, India, Indonesia, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, Madagascar, Malaysia, Maldives, Mauritius, Mexico, Mozambique, Namibia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Portugal, and Seychelles.

[1] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Small Island Developing States and Climate Change, 2005, Bonn, Germany, United Nations, 2005, https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/publications/cc_sids.pdf

[2] Leonard Nurse et al., “Small Islands,” in Climate Change: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability, ed. Michael Field et al., (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 1613-54.

[3] Nurse et al., “Small Islands”

[4] United Nations, “Climate Change,” https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/climate-change.html#:~:text=The%20effects%20of%20climate%20change%20on%20indigenous%20peoples&text=Climate%20change%20exacerbates%20the%20difficulties,rights%20violations%2C%20discrimination%20and%20unemployment

[5] Aideen Foley et al., “Small Island Developing States in a Post-Pandemic World: Challenges and Oportunities for Climate Action,” WIREs Climate Change 769, no. 13 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.769

[6] Julian Walcott, Impacts on COVID-19 on SIDS and their Biodiversity, Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies, University of the West Indies, 2021,

https://nairobiconvention.org/clearinghouse/sites/default/files/Final%20Report_SIDs_draft.pdf

[7] Walcott, “Impact on COVID-19 on SIDS and their biodiversity”

[8] Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States, Vaccinations and COVID-19 Funding for Small Island Developing States, 2021, New York, United Nations, 2021, https://www.un.org/ohrlls/content/covid-19-sids

[9] UNDP, Small Island Developing States: The State of Climate Ambition, 2022, New York, United Nations, 2022, https://climatepromise.undp.org/sites/default/files/research_report_document/Climate%20Ambition-SIDS%20v2.pdf

[10] Gunter Pauli, “The Blue Economy,” Japan Spotlight, February 2011, https://www.jef.or.jp/journal/pdf/175th_cover04.pdf

[11] Matthew Burgess et al., “Five Rules for Pragmatic Blue Growth,” Marine Policy 87, no. 1 (2018), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308597X16307916

[12] SINAY Maritime Data Solutions, “Which SDGs are linked to the sea and how to support them?”,

https://sinay.ai/en/which-sdgs-are-linked-to-the-sea-and-how-to-support-them/

[13] Blue Economy Department, “Seychelles Blue Economy: Strategic Policy Framework and Roadmap,” 2018, https://seymsp.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/CommonwealthSecretariat-12pp-RoadMap-Brochure.pdf

[14] Government of India, India’s Blue Economy: A Draft Policy Framework,” Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister, 2020, https://incois.gov.in/documents/Blue_Economy_policy.pdf

[15] The Borgen Project, “Countries with Blue Economy Strategies,” May 1, 2023, https://borgenproject.org/blue-economy/

[16] Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States (UN-OHRLLS), Accessing Climate Finance: Challenges and opportunities for Small Island Developing States, July 2022, New York, United Nations, 2022, https://www.un.org/ohrlls/sites/www.un.org.ohrlls/files/accessing_climate_finance_challenges_sids_report.pdf

[17] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Green Climate Fund, https://www.greenclimate.fund/

[18] United Nations Climate Change, “Introduction to Climate Finance,” 2019, https://unfccc.int/topics/introduction-to-climate-finance

[19] United Nations Climate Change, “Bilateral and Multilateral Funding,” July 2016, https://unfccc.int/topics/climate-finance/resources/multilateral-and-bilateral-funding-sources

[20] UN-OHRLLS, “Accessing Climate Finance: Challenges and opportunities for Small Island Developing States, July 2022”

[21] UN-OHRLLS, “Accessing Climate Finance: Challenges and opportunities for Small Island Developing States, July 2022”

[22] Ritu Bharadwaj et al., Sinking Islands, Rising Debts: Urgent Need for New Financial Compact for Small Island Developing States, London, IIED, 2023, https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/2023-09/21606IIED.pdf

[23] Dr. Uli Volz, “Using Debt-for-Climate Swaps to Solve Two Crises at Once” (panel speech, Boston, January 13, 2022), Global Development Policy (GDP) Center, https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2022/01/18/webinar-summary-using-debt-for-climate-swaps-to-solve-two-crises-at-once/

[24] United Nations 4th International Conference on SIDS, “About SIDSS4,” https://sdgs.un.org/smallislands/about-sids4#:~:text=The%20fourth%20International%20Conference%20on,St%20John's%2C%20Antigua%20and%20Barbuda

[25] UN-OHRLLS, “Accessing Climate Finance: Challenges and opportunities for Small Island Developing States, July 2022”

[26] OECD, Capacity Development for Climate Change in Small Island Developing States, November 2023, Paris, OECD, 2023, https://www.oecd.org/dac/capacity-development-climate-change-SIDS.pdf

[27] Food and Agriculture Organization, FAO’s Blue Growth Initiative; Blue Finance Guidance Notes, 2020, Italy, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2020, https://www.fao.org/3/ca8745en/ca8745en.pdf

[28] The Nature Conservancy, “Blue Bonds: An Audacious Plan to Save the World’s Ocean,” Perspectives, July 27, 2023, https://www.nature.org/en-us/what-we-do/our-insights/perspectives/an-audacious-plan-to-save-the-worlds-oceans/

[29] Stuart Barrowcliff and Lydia Knoll, “Are ‘Blue Bonds’ Causing a Sea Change in Marine Conservation?” AXA XL, August 16, 2023, https://axaxl.com/fast-fast-forward/articles/are-blue-bonds-causing-a-sea-change-in-marine-conservation#:~:text=Marine%20conservation%2Dlinked%20bonds%2C%20also,%2C%20and%20most%20recently%2C%20Gabon

[30] The Commonwealth, Case Study: Innovative Financing – Debt for Conservation Swap, Seychelles’ Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust and the Blue Bonds Plan, Seychelles, United Kingdom, The Commonwealth, 2020,

https://thecommonwealth.org/case-study/case-study-innovative-financing-debt-conservation-swap-seychelles-conservation-and

[31] Andrew Wright, “Seychelles Leads the Way with First ‘Blue Bond’ to Finance Adaptation,” Global Center on Adaptation, January 03, 2020, https://gca.org/seychelles-leads-the-way-with-first-blue-bond-to-finance-adaptation/

[32] “Bue Bonds, A Blueprint for Ocean Conservation,” Nomura Greentech, May 2023,

https://www.nomuragreentech.com/insights/blue-bonds-a-blueprint-for-ocean-conservation

[33] Dick Labonte, “Blue Bond: The Seychelles Experience,” Collaborative Africa Budget Reform Initiative,

https://www.cabri-sbo.org/uploads/files/Documents/Session-3-Presentation-of-Dick-Labonte-Seychelles.pdf

[34] FAO, Blue Growth Initiative, 2020, https://www.fao.org/3/ca8745en/ca8745en.pdf

[35] Stein Hansen, “Debt for Nature Swaps: Overview and Discussion of Key Issues,” World Bank Environment Department Working Paper No. 1, 1988, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/823691493257754828/pdf/Debt-for-nature-swaps-overview-and-discussion-of-key-issues.pdf

[36] Small States Centre of Excellence, “Case Study: Debt-for-Nature Finance Swap,” https://seyccat.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/SSCOE-Debt-for-Nature-Seychelles-Case-Study-final.pdf

[37] State House Seychelles, Government of Seychelles, “Seychelles Designates 30% of its EEZ as Marine Protected Area,” https://www.statehouse.gov.sc/news/4787/seychelles-designates-30-of-its-eez-as-marine-protected-area

[38] Sedrick Nicette, “Implementation of Marine Protected Areas to Begin in 2022,” Seychelles News Agency, September 22, 2021, http://www.seychellesnewsagency.com/articles/15303/Implementation+of+Seychelles%27+Marine+Protected+Areas+to+begin+in+%2C+official+says

[39] International Institute for Environment and Development, https://www.iied.org/poorest-countries-spending-billions-more-servicing-debts-they-receive-tackle-climate-change

[40] Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, European Commission, https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/news/blueinvest-new-investor-report-features-ocean-investment-opportunities-sustainable-blue-economy-2023-03-09_en

[41] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Investing in the SDGs: An Action Plan for Promoting Private Sector Contributions, October 2014, New York, United Nations, 2014, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2014ch4_en.pdf

[42] Nguyen Nham and Le Thanh Ha, “The Role of Financial Development in Improving Marine Living Resources Towards Sustainable Blue Economy,” Journal of Sea Research 195 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seares.2023.102417

[43] The Blue Peace Financing initiative opens a new and innovative market in sustainable finance. It creates new ways for regional non-sovereign entities managing natural resources, such as river basin organisations, to access financial capital.

[44] United Nations Capital Development Fund, “Invest in Peace through Water: The Blue Peace Financing Initiative is Innovative Sustainable Finance in Action,” https://www.uncdf.org/article/8012/invest-in-peace-through-water-the-blue-peace-financing-initiative-is-innovative-sustainable-finance-in-action

[45] “Who is Pledging Climate Finance at COP28, and How Much?” Reuters, December 7, 2023,

https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/who-is-pledging-climate-finance-cop28-how-much-2023-12-06/

[46] Pollination, “Top Triumphs and Trials from COP28, and What They Mean for You,” December 15, 2023,

https://pollinationgroup.com/global-perspectives/top-triumphs-and-trials-from-cop28-and-what-they-mean-for-you/

[47] Nina Lakhani, “$700m Pledged to Loss and Damage Fund at Cop28 Covers Less than 0.2% Needed,” The Guardian, December 6, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/dec/06/700m-pledged-to-loss-and-damage-fund-cop28-covers-less-than-02-percent-needed

[48] Lakhani, “$700m Pledged to Loss and Damage Fund at Cop28 Covers Less than 0.2% Needed”

[49] UN-OHRLLS, “Accessing Climate Finance: Challenges and opportunities for Small Island Developing States, July 2022”

[50] United Nations 4th International Conference on SIDS, “About SIDSS4”

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV