I. Introduction

In July 2019, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) released its 10th Defence White Paper (DWP), China’s National Defence in the New Era,[1] four years after the Xi Jinping-led military reforms of 2015. The military reforms significantly shrunk the size of Chinese land forces, established the People’s Liberation Army Strategic Support Force (PLASSF), and created five integrated Theatre Commands (TCs) by dissolving and consolidating the erstwhile five Military Regions (MRs). The reforms were consequential, inducing debate about the growth and ambitions of Chinese military power.

The PRC’s 2019 DWP is not very different from the previous DWPs; it remains a mixture of “policy, propaganda and description.”[2] Nevertheless, these official documents are crucial metrics for assessing how the PRC sees the world and the threats it faces, and how the international community must view the PRC.

This paper undertakes an assessment of the latest efforts by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF), People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and the PLASSF to integrate Artificial Intelligence (AI) into its weapons systems, command network, and communications. It evaluates the significance that underlies the changes emerging from the military reforms of 2015 and how the PLA sees its own military requirements, and the implications for India. The analysis also surveys the Chinese military’s Command and Control (C2) structure, and probes the role of AI-enabled weapons systems that the PRC is seeking to integrate as part of its efforts to “intelligentise” the PLA and the other service branches.

A brief caveat is in order: The data used in this analysis are approximations, and the figures are mostly until the year 2018, beyond which the author had no access to relevant data.

II. PLA: From ‘Informationised’ to ‘Intelligentised’ Warfare

The 2015 DWP declared that fighting and “winning informationised local wars” in Preparation for Military Struggle (PMS) was an imperative for the PLA. It established the importance of long-range, precision-strike capabilities and the PLA’s intention to forge ahead with the integration of new strategic technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and cyber capabilities. AI in particular finds a prominent place in the Chinese official discourse. President Xi Jinping, in his address to the 19th Party Congress in October 2017 declared: “We will….speed-up development of intelligent military [AI], and improve combat capabilities for joint operations based on the network information system and the ability to fight under multi-dimensional conditions.”[3]

In the PLA’s immediate radar is the United States (US), which it sees as being bent on pursuing “absolute military superiority.” The PLA is also keeping a close watch on Russia, with its ‘New Look’ military reform initiative, as well as the UK, France, Germany, Japan and India which are strengthening their forces to deal with the demands of warfare in the 21st century.[4] For Beijing, the PLA cannot lag in leveraging the opportunities provided by emerging strategic technologies such as AI. As Elsa Kania, US expert on China’s AI programme pointed out, for the entire length of its history China has been acutely responsive to the evolving character of conflict.[5]

Consistent with Beijing’s previous DWP reports from at least 1993, strategic guidelines have stressed on the need to seize the opportunities of modern technology for application in modern warfare. China’s DWPs have enunciated the staged development of warfare: from mechanisation to informationisation,[6] to intelligentisation.[7] Beijing believes that States that do not build on each one of these phases is likely to be disadvantaged in the evolving military balance of power.

For the PLA, AI finds a prominent focus in what the Chinese call “intelligentised warfare”. China views AI as integral to its efforts to win local wars under informationised conditions. It has a strong desire to not only match the world’s foremost military power, the US, but to surpass it.

China’s Five-Year Plan, called ‘13th Five Year Plan for Developing National Strategic and Emerging Industries (2016-2020)’ lays out the roadmap for R&D, investment and integration of AI with other technical areas, covering robotics, industrial-scale mega projects or ‘AI 2.0’. The document ranks AI 6th amongst 69 major tasks for the Chinese government to pursue. In July 2017, China’s State Council formally announced the ‘Plan for the Development of New Generation Artificial Intelligence’, outlining the three stages for developing AI: 1) establishing a new competitive advantage in the field of AI; 2) generating the development of new industries; and 3) augmenting and strengthening national security. This phased development undergirds the three-step strategy to develop and consolidate AI across all sectors, from the civilian to the military. The first stage requires China to attain a high level of advancement in AI by 2020. In the second, China must become one of the leaders of AI in at least a few technologies by 2025; by that time, AI would have applications in manufacturing, healthcare and national defence. Finally, by 2030, according to the plan, China should become a global leader and hub across the entire spectrum of AI technologies.[8]

In his address to the 19th Party Congress, President Xi made clear the importance of AI in pursuing China’s civilian and military objectives. AI is being studied across the PLA and its officers are particularly following US efforts to leverage this emerging technology.[9] What advantages might this brand of intelligentised warfare bring? Chinese strategists aver that intelligentised warfare enables “shortened” high “tempo”, “accurate” operations, reducing the length of what one Chinese military strategist called “observation-judgment-decision-action”,[10] akin to John Boyd’s conception of the cycle Observation-Orientation-Decision-Action (OODA), or in Mandarin, the “faxian (observation), juece (orientation), jihua (decision), xingdong (action)” loop.[11] The impact of AI on military operations is likely to usher in a “profound military revolution,” according to senior Chinese officer, Lt. Gen. Liu Guozhi.[12] For the likes of Gen. Guozhi, AI, which is central to intelligentised warfare, can trigger dramatic military change, but this process of intelligentisation would build on mechanisation and informationisation. Chinese military writings agree that AI can catalyse transformation in warfare. However, there is ambiguity about whether China sees intelligentisation as a distinct break from the mechanisation and informationisation, or rather a successive phase that builds on the earlier two stages and complements them by helping “develop mechanization and informationization to a higher level.”[13]

Human-Machine Interface

The success of China in effectively integrating AI in its military capabilities is hinged on certain variables, such as the issue of Human-Machine Interface (HMI). This is because the human brain is at the heart of all human activities, including warfare. China refers to ongoing Research and Development (R&D) activities in AI being undertaken by the US Department of Defence’s (DoD) Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). This includes the development in 2008 of the ‘Neuromorphic Adaptive Plastic Scalable System’, undertaken jointly with the American IT multinational company, International Business Machines (IBM). The joint DARPA-IBM project aimed to develop a system whose cognitive capacities will be similar to those found in certain higher-order mammals.[14]

For China’s part, a group of military experts from its Army Command College at Nanjing, Jiangsu has sought to model a combat system or entity, based on a personality. Since psychological and physical behaviour are intricately linked, their study uses Boyd’s OODA loop sequence as a heuristic device by creating corresponding internally driven psychological model along the lines of ‘Necessity-Motivation-Behaviour-Effect’ (NMBE).[15] The experts concluded that AI will help trained commanders, whose personalities are mapped, providing a rich model for algorithm-based genetic optimisation that captures the complexities of commanders and how they respond to tactical situations. It will, according to Chinese analysis, potentially improve combat training for new recruits by creating realistic operational and combat scenarios tailored for a variety of missions.[16] In due course, as the researchers note, AI-driven military training creates an effective virtual environment to hone their skills and this will reduce organisational costs to the Chinese armed services.[17]

In order to comprehensively leverage the advantages of AI or what the Chinese call “intelligent military”, AI has to go beyond developing robotics on land, at sea and in the air. The US in particular, as Chinese analysts point out, seeks to improve C2 and the relay of tactical information through data links using AI. Examples of AI-driven systems, which China is closely monitoring, include the US military’s RQ-4 global reconnaissance aircraft, the unmanned reconnaissance aircraft, the unmanned ground combat vehicle, the unmanned submersible systems, and the Legged Squad Support System (LS3).[18] These are forms of so-called “humanised equipment”, which according to Chinese military experts will have consequences for the balance of military power.[19] It is expected to introduce scientific validity, “fidelity” or reliability and helps, as noted, combat simulation design.[20] Efficiency and the pace of military operations are also important, accruing from the adoption and integration of AI.

Thus, the HMI is equally crucial to understanding why China is investing heavily in AI. For China, AI has to be able to read human intentions and respond rapidly to threats in compressed timeframes with accuracy. Chinese experts point to the role of ALPHA system that featured an Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle (UCAV) that defeated two veteran American fighter pilots in an air-to-air combat simulation exercise. As one of the fighter pilots involved in the simulation, retired Col. Geno Lee of the US Air Force (USAF) observed, ALPHA was “the most aggressive, responsive, dynamic and credible AI [he has] seen to date.”[21]

Civil-Military Integration

For China to ensure effective HMI and fully exploit the opportunities created by AI, its leaders have concluded that the country needs a synergy between civilian industry and the military—or what is known as Civil-Military Integration (CMI). This means that the science and technology that emerges within the civilian industry, must aid innovation and development for the military. After all, AI is dual-use technology: for instance, facial-recognition algorithms can be designed to identify humans walking into a store, as well as identify terrorist activity using UAVs.[22]

To be sure, as Xi Jinping made clear in a speech in September 2017, albeit specifically in the context of the Army’s needs but equally applicable to the other service branches as well—only civilian technology that contributes directly to “actual combat effectiveness” should be adopted and form the basis of the CMI fusion.[23] What the PRC under Xi’s leadership has in mind is a clearly thought-out approach on the military utility of AI. Indeed, China has come a long way in adapting to the changing requirements of CMI.

In the 1990s, the emphasis was more about military contributions to civilian industry and economy. As the 1995 DWP observed, “The transfer of military technology to civilian use has contributed to national economic construction in China.”[24] The economy and technologies which were focused on civilian applications at that time were in need of the military’s technological inputs. There has been a reverse since then, as one American expert on China’s AI efforts noted: “China’s commercial market success has direct relevance to China’s national security, both because it reduces the ability of the United States government to put diplomatic and economic pressure on China and because it increases the technological capabilities available to China’s military and intelligence community.”[25] Therefore, civilian techno-scientific expertise is contributing to military innovation.

To be sure, the strategic context of the 1990s was vastly different from what China faces today. The PRC has also undergone changes in its capabilities and leadership. In the 1990s, Chinese DWPs tended to project a more benign China, whose rise was peaceful and whose leaders were seemingly committed to greater international cooperation in the arenas of arms control and disarmament.[26] In 1993, the strategic guideline was to win local wars using advanced technology. In the 2000s, more emphasis was given to long-range precision strikes, the importance of mechanisation, and applications of Information Technology (IT) on warfare. In a subsequent revision, the 2002 DWP stated that “winning local wars under modern, especially high-tech conditions” was a necessity.[27] Thereafter, the PLA modified it to include the guideline that “local wars are to be fought under conditions of informationization.”[28] The PLA followed this strategic guideline in the subsequent years, until the issuance of the latest DWP in 2019.[29]

Yet the DWPs of the 1990s—and to lesser extent, those of the early 2000s—were also a reflection of China’s relative weakness in the community of nations; today it occupies a position of relative strength. If Deng Xiaoping’s prescription to his country was, “Hide your strength, bide your time, never take the lead,” Xi Jinping’s is more “activist”. As former Australian Prime Minister and Sinophile Kevin Rudd has observed, “Now we see consciously and deliberately a more overtly activist Chinese foreign policy and security policy.”[30] Such shift in China’s foreign and security policy under Xi is an evolution from Deng’s call for a lower profile, rather than a tectonic shift brought about partly by the ascendancy of Xi to the presidency and the chairmanship of the Communist Party of China (CPC).

The Cyber-AI Link

As a consequence of these changes at the helm, China’s military leadership believes that the PLA’s “mechanisation” and “informationisation” were incomplete and in need of “improvement”.[31] Since AI is the cutting-edge technology, it presents unique challenges to Chinese military technologists, strategists and leaders as it does to other countries, including the US and India.

These obstacles include developing “adaptive” software that has built-in learning algorithms that provide parallel transparency and explanations about “decisions, behaviours and factorial affects in real time”.[32] Further, it remains a challenge to develop a genetic algorithm for a given platform such as a UCAV or Unmanned Under Water Vehicle (UUV) that can deal with a multitude of complex problems and cope with randomness and uncertainty that is characteristic of the battlefield.[33] The PLAAF is making serious efforts in this direction by issuing competitive tenders and notices in order to vigorously implement CMI, and the “innovation driven strategy” laid out by Xi Jinping. Notices have been issued for developing, producing and testing autonomous intelligent systems for drone clusters.[34]

Yet, if the PLA and all the other service arms of the Chinese military were to accumulate significant AI-related military capabilities, they could threaten their neighbours and states beyond the Asia-Pacific region. As one Indian expert observed, China faces the challenge of balancing between two competing strains or “contradictory choices”.[35] The first being a grand strategy that limits its aims to the Asia-Pacific region, and the second is due to a growing need and increasing pressures from within to go beyond the Asia-Pacific. The latter would require extending Chinese military power on a global scale, which evokes fears about Chinese imperialism.[36] Whatever the goals of China’s grand strategy, Beijing deems its periphery to be a military priority. Indeed, the Chinese military strategy going back to the early 2000s about “fighting local wars under informationised conditions” would otherwise be meaningless.

Chinese officials sometimes display contradictory views—or at least ambiguity—about whether they treat AI-based intelligentised warfare as a successive stage following mechanisation and informationisation, or as a “composite” of mechanised and informationised warfare. Informationisation, to begin with, is defined by Chinese military officials parlance as consisting of “digitalisation”, “networkisation”, and “intelligentisation”.[37] According to this conception, therefore, intelligentisation is merely a stage within informationisation; it is not a complementary stage. Nevertheless, it is hard to think of a neat separation between informationisation and intelligentisation, given the link between the cyber and AI domains. Indeed, cyber technologies and computer software use AI for better performance. After all, as one of the founders of AI, the late John McCarthy defined AI, it is “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines, especially intelligent computer programmes. It is related to the similar task of using computers to understand human intelligence.”[38] Therefore, informationisation and intelligentisation are inseparable: the former is the basis of developing the latter.

In contrast to humans, cyber networks need to process significantly greater data-processing capacities from multiple sources.[39] AI can enhance security of a cyber-network and computer grid as well by detecting intrusions quickly and accurately—a task that will take humans longer.[40] The PLA thus views cyberspace—with all its associated elements of software and network security on one hand, and AI and machine learning on the other—to be a composite entity.

Financing AI Integration

The PRC has taken specific measures investing heavily in computer chips that are equipped with AI technology. These can optimise graphics, video imagery and speech recognition through Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) by integrating computer hardware and software. A second use of AI chips covers neural networks that enable deep machine learning, which is widely considered the most popular form of AI today. China is also developing neuromorphic-computing chips, another form of AI that replicates the functions of the human brain.[41]

As discussed earlier, the PLA is working to create an AI-driven replication of human military commanders’ action and conduct in the context of battlefield scenarios and conditions. If the PLA is to significantly integrate AI into its combat systems by leveraging the dynamism of the Chinese private and civilian technology sector, it will need an institutional mechanism to do so. Towards this end, the Tsinghua University—China’s premier technical institution—has embarked on a programme called “Military-Civil Fusion for Artificial Intelligence Development.” Under the direction of the Central Military Commission (CMC) Science and Technology Commission, Tsinghua University is establishing the High-End Laboratory for Military Intelligence (HELMI) that will serve as starting point for developing what China calls “AI superpower strategy”.[42] What is most relevant is that Tsinghua University is pushing for greater investments in basic science and applied technology, which will ultimately drive innovation in AI. The creation of HELMI is key to the PLA’s objective of Military-Civil Fusion.[43]

So far, major Chinese technology companies such as Huawei, Baidu, Tencent, and Alibaba have already made substantial investments in AI. They are also collaborating with overseas enterprises. For instance, Baidu, which is China’s top search engine and which has invested in AI, is collaborating with a consortium of Silicon Valley companies. Despite the ongoing trade tensions between the US and China, their tech companies are finding areas of cooperation in AI. There is a view, in fact, that the “AI arms race” between Washington and Beijing may be highly exaggerated given Baidu’s collaborations in AI with American tech giants.[44] To be sure, there are concerns within Washington that Chinese AI is finding its way into Beijing’s state surveillance architecture; still, the private sector enterprises of both countries have forged ahead.[45] Chinese companies have also signed agreements for AI collaboration with various Western universities.

Indeed, China is bullish on its prospects in AI and has significant state investments in this technology for military applications. These investments are believed to dwarf the US’ Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) efforts.[46] The US Department of Defence (DoD) concedes that China and Russia are undertaking more significant initiatives to apply AI to military platforms and missions. This would in turn “leave legacy systems irrelevant to the defence of our people.”[47]

The penetration of AI into PLA military systems is as much about using AI-driven weapons platforms for “remote, precise, miniaturized, large-scale unmanned attacks” as it is about the fundamental method of attack.[48] This point is significant to India. After all, the PRC and the PLA have moved away from attrition-type warfare involving debilitating mass attacks that cause heavy casualties, to non-contact warfare involving long-distance and standoff range delivery of accurate and lethal firepower that enables the PLA to secure a quick, low-cost and decisive victory.[49] AI will augment such capacity. The Indian armed services will face the same dire predicament that the US DoD observed about legacy weapons systems effectively preventing the defence of the nation and its people.

III. Potential Impact of A.I. on the Command and Control of the Chinese Military

While the integration of AI in combat platforms and operations is important, military organisations, including the PLA are likely to face adaptation-related challenges involving their Command and Control (C2).[50]

The military reforms introduced by Xi Jinping in 2015 ushered in substantial changes in the military command system of the PRC. China dissolved the erstwhile seven Military Regions (MRs) and established five Integrated Theatre Commands (ITCs) under a single operational commander. The PLA’s new regional command structure is geographically limited to Chinese territory, which means that it is not exactly the same as the US’ worldwide combatant command system.[51] China has also made efforts to ensure that in the event of conflict, high levels of trans-theatre mobility and logistical supply are sustained.

The newly established military command structures will have to be nimble and flexible to cope with the demands and complexities that come with not just the mechanisation and informationisation of warfare, but now AI’s role in it. The PLASSF is PLA’s organisational entity mandated by the 2015 military reforms to undertake space, cyber and electronic warfare operations. Presumably, the PLASSF will undertake AI-related missions or cyber missions that are AI-enabled. Since the PLASSF’s role is primarily focused on Command and Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) capabilities,[52] it is likely that AI will be brought under the ambit of the SSF. The SFF has a significant outreach programme as part of CMI to engage universities and private software industries for integration with civilian institutions and commercial enterprises. In 2017, the Deputy Commander of the SSF Li Shangfu, who is now a full general, was shifted to the Central Military Commission’s Equipment Development Department, indicating the importance the Chinese military attaches to the acquisition and integration of emerging technologies such as AI.[53] Beyond the civil-military interface to tap opportunities created by emerging technologies, the Chinese military could integrate AI in a number of platforms.

One such platform is the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN) expanding global presence that requires China to partially reconfigure its command system that extends beyond the South China Sea and the Western Pacific. China already has a base in Djibouti, and it is increasing its naval presence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) by replenishing hubs such as Hambantota, which is not yet a base but a port destination for PLAN vessels to secure resupplies and repairs. PLAN submarines have made frequent forays into the IOR, the latest of which was their entry into the Andaman Sea which links the Eastern Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. The frequency of these deployments has surged to ten in the last few years, with longer operational deployments and a more prolonged presence in the Andaman Sea.[54] These activities are telling signs of things to come for India and other IOR littorals. As the PLAN’s reach grows, AI will play a prominent role in the ongoing efforts by all the service branches of the Chinese military. PLAN vessels, as well as the PLAAF and PLA platforms and weapons systems, will soon have AI-equipped capabilities.

Another area of potential is developing current facial-recognition technology to build autonomous military combat platforms that act without human controllers’ intervention based on what it deems a hostile visual appearance and voice.[55] The PRC already deploys facial recognition technology in detention camps to identify Uighurs in the Xinjiang province.[56] There are existing military drones that can fly to a zone where a target is located without the aid of satellite navigation, identify a target visually, deliver ordinance to destroy it, and return to base without any human intervention.[57]

Therefore, the implications AI will have on military C2 requires careful assessment. What role might AI play in weapons systems and C2 structure of the Chinese military in both peacetime and wartime?

Self-Reliance

The real test for China’s command structure is meeting the complexities and challenges that come with the adoption and integration of AI. AI involves autonomous systems of warfare. The C2 architecture could move incrementally from ‘decision-assist’ to ‘decision-enable’, transitioning to platforms with built-in independent decision-making capacities. This is something the Chinese leadership will need to address. At the same time, Xi and the PLA, notwithstanding the 2015 military reforms that altered the C2 architecture for integrated joint operations in wartime, will have to overcome their tendency for excessive centralisation, particularly during wartime operations, if AI-based platforms and sensors are to be fielded. After all, the PLA is the Party Army and not a national military. The CPC and Xi-led leadership’s insistence on “absolute leadership” means that there are bound to be centralising proclivities,[58] which could potentially undermine the effective use of AI while limiting the Chinese leadership’s excessive reliance on AI for command-related decisions during operations. Insistence on the complete loyalty of the PLA to the CPC, as Indian experts have observed, is a reminder to the Chinese armed services that the CPC enjoys and retains primacy.[59] The challenge for China will be in finding the balance between leveraging automated warfare without undermining human command.

While information or cyber technology has substantially penetrated Chinese warfighting capabilities in the areas of C4ISR and there is substantial effort underway for deeper integration across sensors and platforms, AI, at least in part, is the answer. However, challenges remain in securing precise data generated by multiple sensors, improving sensor-to-shooter capabilities, and enabling command decisions to be accurate and swift. AI is considered a means to overcome some of the complexities of fusing and processing data from multiple and varied information sources.[60] China is also focusing on developing AI-integrated platforms; among them are the PLA’s AI-equipped ground combat vehicles,[61] which would be highly relevant to India’s defence preparedness in land warfare. Effective integration of AI can help China tilt the military balance decisively in its favour, or at the very least, along the disputed Sino-Indian boundary.

Nevertheless, China recognises that developing autonomous weapons can generate problems that have not been fully anticipated. There is no evidence yet to suggest that China wants to completely dispense with the human element and pursue the development of exclusively machine and robotic warfare.[62] Despite recent efforts to test unmanned vehicles as part of the “next generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan (AIDP)”, the Chinese technologists concede the difficulties confronting them in developing an autonomous combat vehicle that can identify targets and sustain effective human-computer interaction.[63] Every stage presents its own technical challenges and problems to overcome.[64] Notwithstanding a strong motivation for the development of AI, the PRC sees AI facing several weaknesses. These include the absence of quality talent, poor technical standards, underperforming software platforms, and weakness in semiconductor development. In addition, AI development lags behind advanced industrialised states especially in the development of core algorithms, key equipment, high-end chips, and several other applications of AI in platforms and systems.[65] Based on Chinese espionage cases in the US, American investigators have discovered that China is seeking out propulsion technology, advanced sensors, autonomous operation and data links.[66]

Despite these difficulties and limitations, there are efforts being made to test and integrate AI into military platforms. As part of a Politburo study session conducted in 2018 which is integral to the PRC’s AI strategy, Xi Jinping made clear that he wants to see the PRC become self-reliant in AI and overcome its exposure to “external dependence for key technologies and advanced equipment.”[67]

Offensive and Defensive Systems

Beyond self-reliance, however, some Chinese strategists see enormous possibilities of transcending the OODA Loop to the extent the human element may be reduced significantly with the loop becoming more “automatic and flexible” with AI, facilitating faster and accurate decision-making, based on “information agility” from multiple sensors.[68] Effective command decisions during military operations, however, are based not only on accurate intelligence, but the time the commander has in responding to threats. This is where AI plays an important part as it could shrink decision time and significantly improve the sensor-to-shooter loop. Automated command systems obviate the danger that decision time and accuracy could suffer due to human error. AI helps extract certainty out of uncertainty, thereby making command more effective as well as making autonomous weapons systems more lethal.

Nevertheless, China is cognisant of the need to balance the human and machine dimensions of decisions in military command and operational matters. After all, even the chairperson of Alibaba did caution the Chinese government about the emergence of AI and machine learning as potential triggers of World War III.[69] Consequently, it is fair to conclude that Chinese “intelligent systems” will be driven by high levels of automation for defensive and offensive missions. Defensive capabilities would include air and missile defences, which might not pose a significant threat particularly to states such as India, Vietnam, Japan or the US. However, what China’s adversaries have to be concerned about are the PLA’s autonomous or AI-enabled platforms, geared for offensive missions and operations covering unmanned aerial platforms and AI-driven, long-range rocket launch and ballistic missile systems and, potentially, UUVs. According to one analyst, the Chinese leadership will develop and field intelligent systems geared for “tracking, targeting and attacking” the enemy under clear guidance and intentions of commanders.[70]

Generally, the PLA under the leadership of Xi sees the imperative of creating an ecosystem for cutting-edge, AI-related R&D, leading China’s military leaders to vigorously invest and integrate AI into weapons systems as part of their efforts towards “intelligentisation”.[71] It remains to be seen how much success they can have, but the effort and purpose underlying their quest to attain excellence in the field is undeniable and far surpasses that of India’s.

IV. R&D and Strong Industrial Foundations

The PRC is implementing the application of AI across industries, aided by the country’s strong manufacturing base. Since AI is disruptive technology, it requires bold vision to alter entrenched work cultures and a management that can enable change rapidly. It requires the management of companies to dare and encourage initiative; testing, piloting and even failing will have to happen early in order to test the limits of the technology.[72] AI requires organisational cultures to aggressively push for innovation.[73] (See Table 1 in Appendices for the investments China is making in AI. It is noteworthy that India does not even figure in the table.)

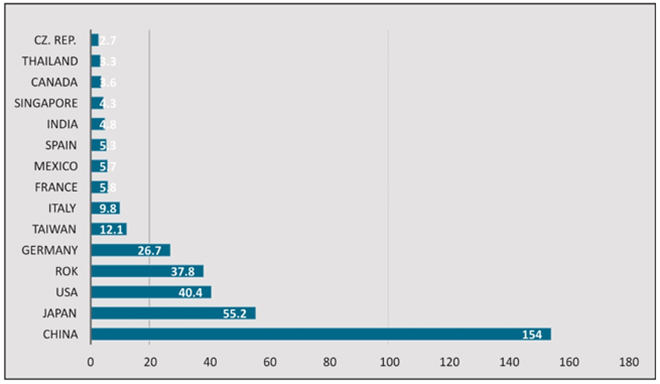

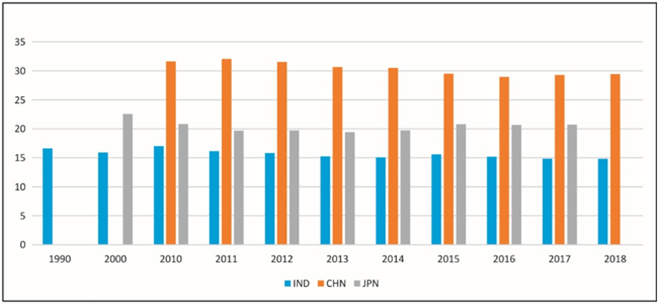

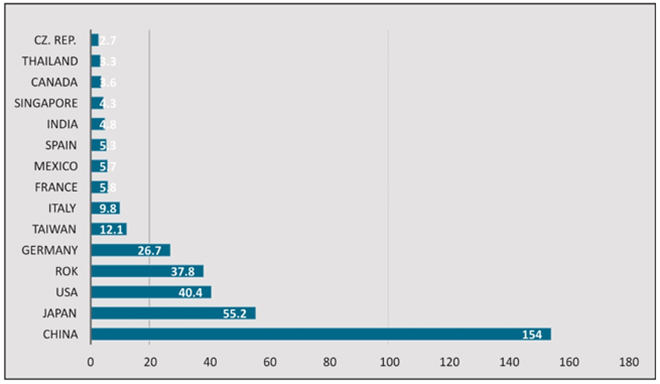

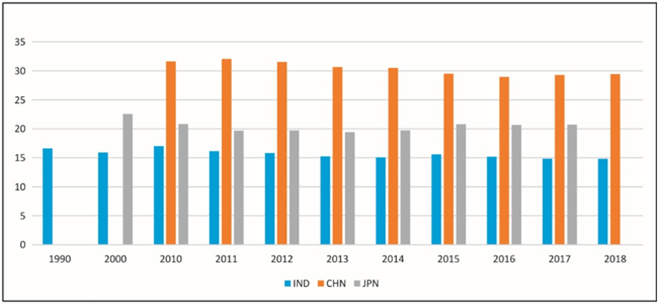

Figure 1, meanwhile, illustrates that amongst the 15 largest end-users of robotics, China is at the top and India is 11th. As of 2018, China has installed 154,000 industrial units as opposed to the 4,800 by India. The top five states in the list have a large manufacturing base that accounts for a sizeable percentage of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Thus, an important factor explaining China’s capacity to expand AI applications across industries is manufacturing. As the Director of the Artificial Intelligence Research Center (AIRC) in Japan Junichi Tsujii observed, “Japan has a number of strengths with regard to AI research. One is its technological foundations in manufacturing.”[74] See Figure 2 for the differential in manufacturing’s contribution to the GDPs of Asia’s three largest economies. India at no stage has crossed 18 percent in the last 30 years.

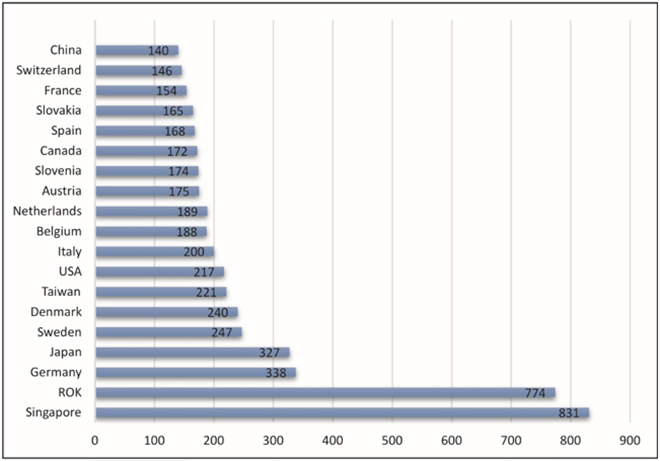

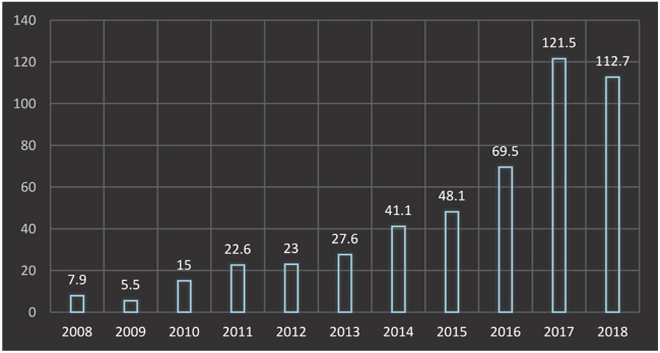

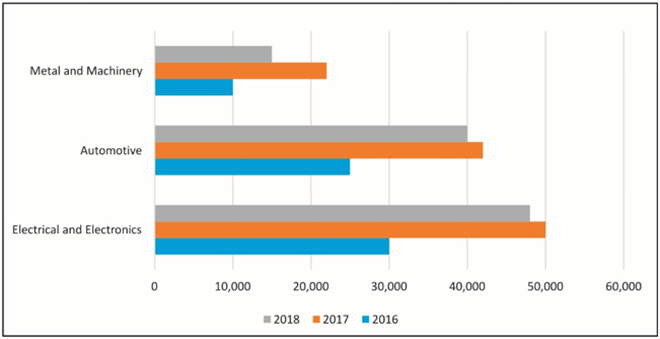

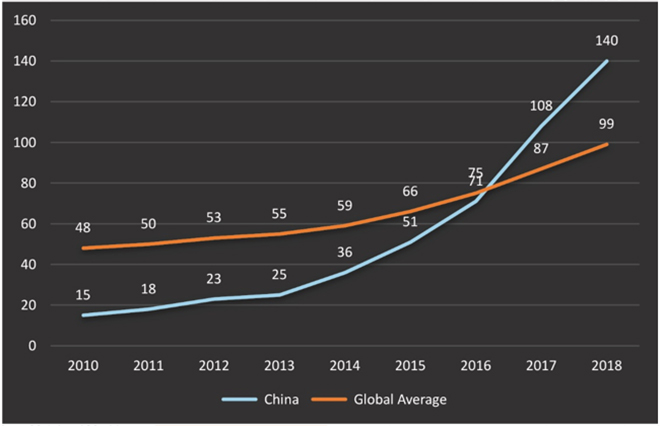

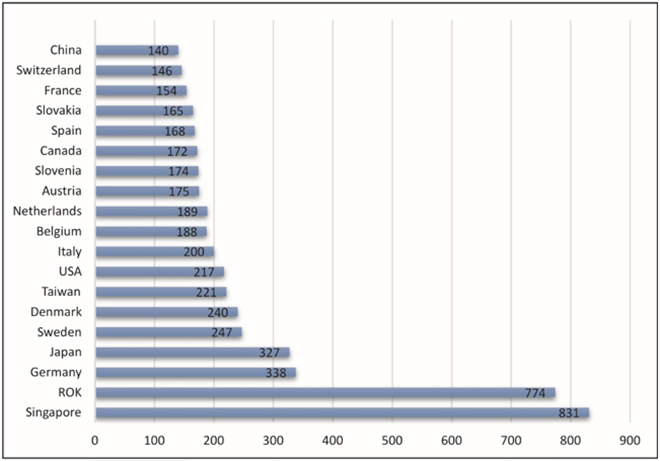

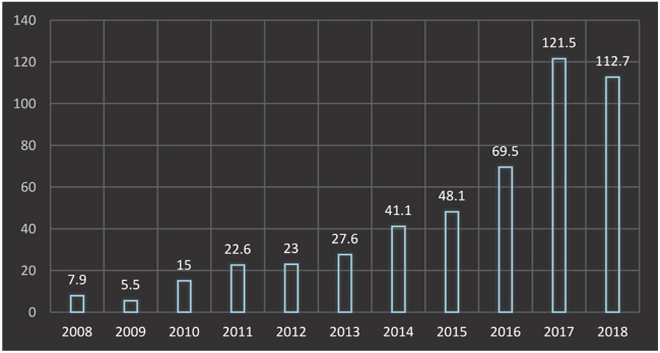

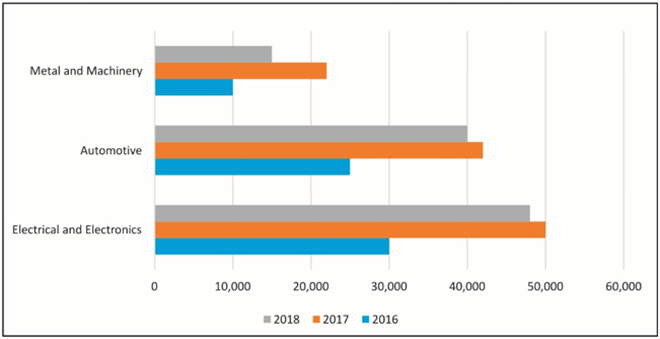

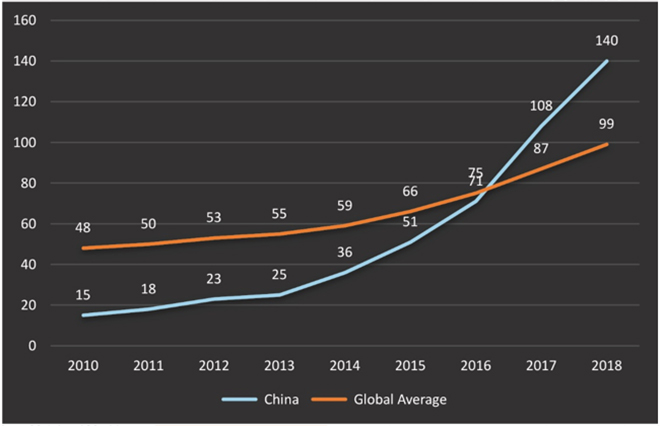

If anything, the contribution of manufacturing to India’s GDP has contracted in the last two fiscal years to under 15 percent of GDP. Robot density is low generally in Asia, and China ranks second from the bottom in the number of robots installed for every 10,000 workers as shown in Figure 3, indicating robotic automation is not as deep as it is in Europe and America. However, Figure 4 shows annual installation of robots in China between 2008 and 2018 has increased by 1326.58 percent, despite a marginal dip in 2018. Installation of robots by industry between 2016 and 2018 also indicates that the PRC, despite a slight dip in 2018 represents a robust increase (See Figure 5). Further, robot density for every 10,000 workers is also a good measure for gauging automation in China. As Figure 6 shows, China’s robot density surpassed the world average in 2017 and 2018.

To be sure, robotics adoption in manufacturing is only one indicator of potential strength in AI. More demanding is cognitive robotics, which goes beyond “industrial production organised around the machine; it is calibrated according to its environment and tolerated minimal variations.”[75] On the other hand, Cognitive robotics necessitates human-like behaviour requiring an optimisation of learning through perception, understanding, learning from experience and imitation, which are still demanding benchmarks for China to achieve or at least a work in progress. Nevertheless, these robotics figures do provide a reasonable indication of the foundation from which China can build an AI ecosystem. Table 2 provides a brief description of the subfields of AI, which are highly complex and evolved.

Finally, China’s absolute spending in scientific Research and Development (R&D) is roughly nine times higher than India’s, and China’s number of qualified researchers is more than seven times higher than India’s (Table 3). A study published in December 2019 concluded that China spends almost US$ 8.5 billion on AI (See Table 4). What is more revealing is that despite the data in Table 4 indicating billions in AI R&D expenditure, China spends only a “small fraction” of US$ 290 million on basic research in civilian AI.[76] Such low expenditure would go to some extent against the prescriptions made by leading faculty at Tsinghua University, discussed in an earlier section of this paper, calling for greater emphasis on research in basic science as the basis for civil-military fusion and innovation. The data is also instructive about the priorities of the PRC: Beijing sees greater value in applied and experimental AI research and defence-related AI research, which are 18 and nine times higher, respectively, than investment in basic AI research (Table 4).

The PRC’s commitment to harness the power of AI rests on relatively firm industrial foundations and R&D in applied and defence AI, receiving a commensurately aggressive push by the leadership in the military domain. In the context of military applications of AI, the American expert on Chinese AI Gregory Allen observed, “Despite expressing concern on AI arms races, most of China’s leadership sees increased military usage of AI as inevitable and is aggressively pursuing it. China already exports armed autonomous platforms and surveillance AI.”[77] Among its most crucial export markets are Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

China is experimenting, developing and deploying Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGVs), AI-enabled satellites, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVS), Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) and unmanned ground warfare platforms. The PRC has several military technological initiatives with AI applications. Across the Chinese armed services, there is a substantial effort underway to develop, integrate and become a world leader in the military applications of AI technology.

The PRC is using and converting what were otherwise manned tanks such as its large inventory of T-59s into unmanned platforms. One might assume fielding an obsolete tank, such as the T-59, is surprising, but China seeks to derive other experimental and mission-related benefits from this platform, such as a test-bed for unmanned future armoured systems or to increase firepower, which inevitably would require shedding protective armour.[78] Indeed, the T-59 lacks protection, making it highly vulnerable to enemy anti-tank weaponry. While protection is important for manned combat vehicles due to the presence of a human crew who are highly exposed and vulnerable and thus need additional armour, an unmanned T-59 tank proffers firepower benefits and eliminates the requirements for protection. However, a firepower-packed unmanned tank poses no risk to human crew and it can help in the early stages of a war by delivering significant ordinance against enemy targets during military operations.[79] While survival of the crew is not the only criteria in war, developing AI-based weapons systems and platforms is consistent, at least in part, with China’s objective of limiting combat casualties. It dovetails well with the PRC’s historical efforts to reduce debilitating and bloody combat engagements by prosecuting operations from great distances, decisively and at low cost. This requires enhanced firepower with increased lethality, which is what AI enables.

On the other hand, the T-59 could simply be a test bed for validating and experimenting with existing and evolving AI technology. China is presumably ascertaining how AI equipment may be integrated into newer unmanned land-based platforms.[80] Other areas where Beijing is making investments is in Underwater Unmanned Vehicles (UUVs). It is building the Wanshan Marine Test Facility on the gateways leading to the South China Sea (SCS) to test underwater systems for surveillance, reconnaissance and combat.[81] The SCS is a source of tensions and potential conflict between the PRC and its neighbours such as the Philippines, Brunei and Malaysia, who have rival claims over the reefs, atolls and islands in the SCS. Just as it is the case with land-based systems, a key rationale behind the development of unmanned underwater systems is to reduce and obviate risks to humans. AI is crucial to this endeavour and integral to the PRC’s innovation-driven strategy for technological excellence that reciprocally benefit the civilian and military domains. As Collin Koh put it, “While the South China Sea is part of the picture, this new test range [Wanshan] isn’t just designed for this dispute. With this test range, China can trial a whole range of unmanned vessels, both for its own use but also in no small part for export.”[82]

China has also sought to expand the use of AI to satellite technology. Given AI’s dual use, China has sought to develop AI-driven military capabilities derived from its decade-long scavenger satellite programme. Equipped with a triple eye sensor, the smaller satellites which can weigh as little as 10 kilograms and determine relative speed, random rotation and shape can, with the help of a single axis robotic arm, latch onto uncooperative targets such as a non-functioning spacecraft that are moving in low earth orbit.[83] Thereafter, the satellite fires its thrusters, allowing it to redirect the dead spacecraft to de-orbit by helping it burn through the earth’s atmosphere.

In the context of military operations, however, these satellites could remain glued to their space junk, eluding detection by the adversary’s ground-based sensors and neutralising anti-satellite measures.[84] In the last decade, China has launched ten experimental Scavenger satellites. Based on declassified information, the Scavengers are designed for clearing space debris—a technology which the European Space Agency (ESA) and the United States have been developing as well.[85] Yet the spin-offs from the PRC’s Scavenger programme have also found applications in the military use of robotics, UAVs and smart weapons. Due to their experimental status, the satellites have yet to meet production requirements and deployment.[86]

Beyond satellites, China has invested, developed and marketed UAVs, which for many years were an American preserve; China today is widely considered a significant actor in drone development and export. The most impressive of China’s aerial platforms is the G-11 stealth drone,[87] considered amongst the most advanced UAVs in the world with a combat radius of 1000 km and a flight ceiling of 18,000 meters. This system has completed development and is in service.[88] In addition, following their initial public appearance as prototypes, China has deployed the WZ drone, which like the G-11 is High Altitude Long Endurance (HALE) UAV, but not stealthy.[89] It is deployed on bases in the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) and was active during the Sino-Indian Doklam military-stand-off in 2017.[90] Chinese military drones are a derivative of American UAVs such as the MQ-Reaper and Predator. The reason for China’s success in military drone technology is due to its extensive espionage against the US, enabling the PRC to close the gap in weaponised UAVs, which are stealthier, carry higher payloads, and are long-endurance platforms.[91] Therefore, a large number of Chinese drones are not exclusively a product of state-led top-down innovation, but AI-enabled systems that are the result of theft.[92]

A final area of AI application is missile technology. China’s next generation cruise missile will be AI-enabled. They are expected to be tailored for specific scenarios according to Chinese military designers. Combat conditions will determine the type of missile to be used. Chinese missile technologists are adopting a ‘plug and play’ approach that will enable military commanders to determine what type of missile to use in a given situation. As Wang Changqing, a senior designer observed, “Our future cruise missiles will have a very high level of artificial intelligence and automation.”[93] Two variants of cruise missiles are on the anvil. The first is a “fire and forget” missile and the second will involve the intervention of the commander either to make in-flight changes or terminate a mission.[94] Evidently, China is pursuing missile capabilities that are flexible, cost-efficient, modular, and AI-enabled.[95]

V. Implications and Challenges for India

1. Investing in basic science as foundation for AI. In order to develop and consolidate an emerging technology such as AI, India will need to invest in the basic sciences. As CNR Rao, one of India’s premier scientists stressed in 2013, “India has to learn to use the latest results of science and technology for innovation. The future of India is secure if it invests in basic science and science education. Only countries that have advanced scientifically have made progress, while those who neglected it are not known.”[96] To be sure, India has improved its standing in the Global Innovation Index (GII) since Rao made those comments—it has climbed from 67 in 2013 to 52 at present, and is performing above expectations given the limited funding it allocates for research. Nevertheless, there is immense scope for improvement, and bigger funding must be allocated to the basic sciences[97] if it aims to even come close to China in innovation. Investments in both hardware and software are required. The hardware dimensions include a strong manufacturing base, and the software elements include the formulation and development of algorithms, vision, language, analytics, Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) that seeks to understand and integrate human perceptions.[98]

2. Creating a government-driven public organisation for AI. Among the core functions of such an organisation should be to raise public awareness about AI and its importance across sectors. For instance, a NITI Aayog discussion paper on AI released in June 2018, while focused on the commercial and civilian aspects, also dwelled on the military applications of AI. The paper documented the lack of awareness about AI, the high resource cost, and the absence of an AI ecosystem and of core research in fundamental AI technologies.[99] Although the report saw considerable value in AI’s contribution to manufacturing, it saw it as a “beneficiary” rather than as a foundation for the development of AI. India might end up becoming a mere importer of AI rather than an innovator, developer and incubator.[100] China, meanwhile, has a robust manufacturing base which has served as the basis for its adoption of AI across sectors including the military. Japan is another AI-capable country, primarily due to its potent manufacturing sector and historical experience in investing and developing robotic technology. India will also need a government-supported institutional equivalent of both Japan’s and PRC’s Artificial Intelligence and Research Center (AIRC). On the military side of AI, India will need to demonstrate greater purpose and emulate China by establishing an institutional equivalent of the National Innovation Institute of Defence Technology under the aegis of a National University for Defence Technology (NUDT).[101]

3. Nurturing AI across the government and the private sector. AI has only recently gained the attention of the Indian government. While private sector enterprises do exist, they have only started making investments in skilling human capital, educational institutions have begun preparing curricula and coursework for AI, and professionals within the technology sector are only starting to update their skills sets.[102] Even as India’s approach is state-led like China’s or the US’, it is far less aggressive. A key impediment for AI gaining traction is the cost of failure, which is steeper in India relative to the PRC or let alone the US. Although in the US, AI innovation is largely driven by the private sector, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is playing a key role in AI defence R&D. Historically, with a few exceptions, such risk-aversion has blighted Indian innovation and entrepreneurship across sectors.[103] Indeed, as the Indian industrialist and entrepreneur Baba Kalyani who runs the world’s largest forging company Bharat Forge put it, the relationship between the government and the private sector is a two-way street: the government creates the incentives and regulatory mechanisms and transparency, but industry must take risks and deliver.[104] Developing, nurturing and retaining human talent is crucial to success in AI.[105] Further, as AI is cutting-edge technology, the Indian penchant and proclivity for Jugaad or low-cost innovation will not suffice in making India a leading developer and user of AI technology in the civilian and military domains.

4. Expanding AI Defence R&D. While India’s premier Research and Development (R&D) organisation, the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) runs the Center for Artificial Intelligence and Research (CAIR) focused on the development AI for defence, its adoption of AI and AI-enabled systems is still in its nascent stage. It is hard to ascertain the funding the CAIR receives and status of its AI initiatives and programmes. So far, the DRDO has developed a few unmanned systems, one visible example of which is the Mission UNmanned TRAcked called the Muntra, which has three variants – reconnaissance, mine detection, and surveillance.[106] More than even China, the challenge lies in determining how much India spends on AI-related defence R&D. This paper has already drawn attention to the wide gap between China and India in general spending in scientific research in absolute terms (See also Table 3 in Appendices). This may be the best indicator of China and India’s relative strengths in AI, particularly in defence. Despite limitations such as an absence of technical maturity and other constraints including attracting and developing human talent, as one American AI analyst recently put it, “the defence enterprise is ripe with areas that are appropriate for the application of AI.”[107] China is already well placed to exploit the emergence of AI and its applications to defence; India will need to demonstrate greater urgency on the matter.

VI. Conclusion

In the recent few years, the PRC has been engaged in intensive efforts to integrate artificial intelligence (AI) in its military capabilities, at least into the weapons systems and cyber networks of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the other service branches. The country has made significant investments in these efforts. So far, however, the role of AI in the command architecture remains unclear and uncertain; indeed, there have even been conflicting evidence.

China may want to test AI-based weapons that reduce human intervention to a degree that many countries including the US might not be inclined to doing. Relative to China’s, too, India’s efforts are modest, if not outrightly negligible. New Delhi will need to be strategic in its own efforts to integrate AI applications in its weapons systems. This requires identifying, first, which weapons systems should be the focus of AI investments, and also in what missions AI may be appropriate. One area where India should seek to emulate China is the acquisition of AI-enabled capabilities that contribute to military effectiveness.

In addition to selectivity and effectiveness, there is a case to be made for expanding collaboration with an AI-capable state, such as Japan. At home, India needs better data: not only collecting it and processing it with the help of human talent, but also nurturing human talent to engage in Big Data analytics. After all, human brain power is as important for developing an emerging technology such as AI.

While governments generally tend to withhold data on defence R&D, at a minimum, the Indian government needs to practice transparency over data, as well as the investments it is making in basic civilian AI research. This will help not only with maintaining an audit on civilian AI research, but equally important, in measuring progress, assessing priorities, and identifying new initiatives.

Appendices

Table 1. Share of Active and Major Players in AI

|

AI Piloting |

AI Adoption |

Share of Active Players in AI |

| China |

53 percent |

32 percent |

85 percent |

| USA |

29 percent |

22 percent |

51 percent |

| France |

29 percent |

20 percent |

49 percent |

| Germany |

29 percent |

20 percent |

49 percent |

| Switzerland |

31 percent |

15 percent |

46 percent |

| Austria |

29 percent |

13 percent |

42 percent |

| Japan |

28 percent |

11 percent |

39 percent |

Source: Boston Consulting Group

Table 2. Subfields and Technologies Underpinning Artificial Intelligence

| Subfields |

Brief Description |

| Neural Networks |

Build on the area of connectionism with the main purpose of mimicking the way the nervous system processes information. |

| Deep Learning |

Is part of machine learning and is usually linked to deep neural networks that consist of multilevel learning of detail or representations of data. |

| Fuzzy Logic |

Focuses on the manipulation of information that is often imprecise. Most computational intelligence principles account for the fact that, whilst observations are always exact, our knowledge of the context, can often be incomplete or inaccurate as it is in many real-world situations. |

| Evolutionary Computing |

Relies on the principle of natural selection, or natural patterns of collective behaviour. The two most relevant subfields include genetic algorithms and swarm intelligence. |

| Statistical Learning |

Is aimed at AI employing a more classically statistical perspective, e.g., Bayesian modelling, adding the notion of prior knowledge to AI. These methods benefit from a wide set of well-proven techniques and operations inherited from the field of classical statistics, as well as a framework to create formal methods for AI. |

| Ensemble Learning |

Is an area of AI that aims to create models that combine several weak base learners in order to increase accuracy, while reducing its bias and variance. For instance, ensembles can show a higher flexibility with respect to single model approaches on which some complex patterns can be modelled. |

| Logic-based artificial Intelligence |

Is an area of AI commonly used for task knowledge representation and inference. It can represent predicate descriptions, facts and semantics of a domain by means of formal logic, in structures known as logic programs. |

Source: AI and Robotics, UK-RAS

Table 3. Absolute R&D Investment

|

Absolute R&D in USD Billions |

Number of Researchers |

| China |

409.2 |

3,923 |

| India |

50.3 |

546 |

Source: UBS Research

Table 4. Consolidated Estimates of China’s AI-related R&D for 2018

| Civilian AI R&D – Basic Research |

– 650 million RMB (USD 90 million) to – 2 billion RMB (USD 290 million) (low to moderate certainty) |

| Civilian AI R&D – Applied Research and Experimental Development |

– 11 billion RMB (USD 1.6 billion) to – 37 billion RMB (USD 5.4 billion) (low certainty) |

| Defense AI R&D – All |

1.8 billion RMB (USD 300 million) to – 19 billion RMB (USD 2.7 billion) |

| Total AI R&D |

– 13.5 billion RMB (USD 2.0 billion) to – 57.5 billion RMB (USD 8.4 billion) (very low certainty) |

Source: Center for Security and Emerging Technology, Georgetown University

Figure 1. Largest end-users of industrial robots (Units ‘000)

(World Robotics 2019)

Figure 2. Manufacturing Value Added (percent of GDP) (World Bank)

Figure 3. Robots installed per 10,000 employees (World Robotics 2019)

Figure 4. Annual Installation of Robots in China for ‘000 Units

(World Robotics 2019)

Figure 5. Annual Installation of Robots in China in three major industries, 2016-2018

(World Robotics 2019)

Figure 6. Robot Density in China Relative to World Average

(International Federation of Robotics)

Endnotes

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV