-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Patrick Walsh was a visiting Australian researcher at Observer Research Foundation (ORF). He studies at the University of Queensland, and came to New Delhi in 2016 on the New Colombo Plan Scholarship, facilitated by the Australian government’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). Patrick has a strong interest in Pacific affairs, spending the first half of 2016 studying at the University of the South Pacific (USP) and working within the region’s international relations sector. During his time at ORF, Patrick also published with the East Asia Forum, The Lowy Institute, and The Diplomat. This Occasional Paper was written in November 2016 and does not cover events that may have transpired since the time of writing.

Image Source: A guidebook on Pacific diplomacy: India looks to the ‘Far East’

Introduction to the Pacific

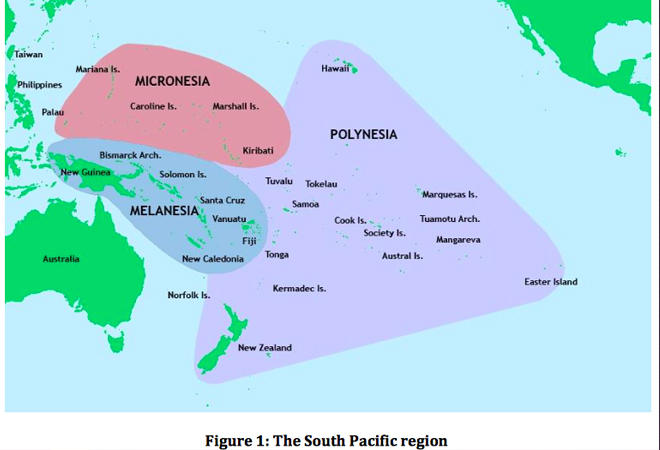

A smattering of islands connecting Asia with the Americas, the Pacific region accommodates a mosaic of states and non-states with varying degrees of self-governance: sovereign nations, recognised colonial territories, non-recognised colonial territories (West Papua, Bougainville), states of ‘compact association’, and states of ‘free association’. The 14 independent nations are approximately sub-divided into three ethnographic and political regions: Micronesia houses the nations of the Federates States of Micronesia, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Nauru and Palau; Melanesia includes Fiji, Papua New Guinea (PNG), the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu; and Polynesia comprises the Cook Islands, Niue, Samoa, Tonga and Tuvalu. The Pacific Ocean is also home to the non-self-governing inhabited territories of Tokelau (New Zealand), New Caledonia (France), French Polynesia (France), Wallis and Futuna (France), American Samoa and Guam (USA), Pitcairn (Britain), Rapanui (Chile), as well as a collection of non-inhabited bases in the Northern Pacific administered predominantly by the US.

The Pacific islands region was one of the last in the world to undergo decolonisation, with Samoa first to declare independence in 1962, followed by a wave of other Pacific island societies ending centuries-long colonial rule: Fiji (1970), Papua New Guinea (1975), the Solomon Islands (1978), Tuvalu (1978), and Vanuatu (1980). Independent regional political representation of the Pacific islands did not occur until their split in 1971 from the colonial-led South Pacific Commission (SPC). The new ‘South Pacific Forum’ (in 1999 renamed the Pacific Islands Forum) was a commitment to independence and self-determination in the Pacific, as well as regional integration and collaboration, and intentionally excluded the SPC colonial powers: France, the Netherlands, Britain, and the US. [i] The remaining two powers in the SPC, Australia and New Zealand, were invited to join the South Pacific Forum after debate; Fiji led support for the two regional neighbours as strategic partners for the newly sovereign Pacific island states. [ii]

Pacific Island States: Geographic and Ethnographic Groupings

Today, the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) is still the premier political organisation of the Pacific island nations, and has become more confident in its engagements with its own region, and the world. The PIF currently has 18 members: the 14 independent Pacific island states; Australia and New Zealand; and, most recently, France’s French Polynesia and New Caledonia which attained full membership last year at the 47th annual Pacific Islands Forum. [iv] Significantly, the Pacific is also experiencing strong sub-regional political organisation and lobbying, with the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), the Pacific Islands Developing Forum (PIDF) and the Polynesian Leader’s Group (PLG) as principal examples. [v] The Pacific engage with the international community (United Nations) through key lobbying groups such as the Pacific Small Island Developing States (PSIDS), the G77 (+China), and the Association of Small Island States (AOSIS). [vi]

It is a fair assertion that the Pacific is generally underappreciated and misunderstood by the wider world, and such lack of insight has caused many diplomatic blunders and failed attempts of cooperating with the region. The historical — and perhaps still conventional view of the Pacific as the ‘backwater of international relations’ — is outdated and inaccurate; [vii] a growing trove of literature is taking heed of the increasingly outspoken and activist Pacific presence at international fora and rightfully regards the Pacific islands as complex, fierce and high-achieving global actors. [viii] Importantly, the Pacific should not be confused as a vague annex to the broader geographic areas of ‘Asia-Pacific’ and ‘Oceania’; such terms usually never appreciate Pacific island states as a diverse grouping of vital, able and increasingly relevant global actors. In fact, using such semantics when liaising with Pacific island states quickly reveals a lack of understanding of the region and the absence of imagination for bilateral or multilateral engagement with Pacific actors.

Despite such frustrations and its many developmental challenges, the Pacific states have forged ahead, particularly in the last decade, to capitalise on the increased leveraging power afforded to them by a changing world order. Indeed, the Pacific has become a leading voice of the 21st century. [ix] This is particularly in reference to the Pacific leaders’ consistent politicking at the United Nations (UN) on mitigating the effects of climate change and pushing for a global commitment to carbon emission reductions. The PSIDS-led ‘High Ambition Coalition’ at Paris’ COP21, headed by then Foreign Minister of the Marshall Islands Tony De Brum, has been widely credited for driving the Paris Agreement within the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). This agreement committed parties to limiting the warming of ocean temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius. [x] As the region is home to some of the world’s countries most vulnerable to extreme weather events and rising sea levels, Pacific leaders have long been agitating for greater global collaboration on matters of renewable energy, maritime resource management, and sustainable fisheries. [xi]

In recent years, the Pacific region has also been gaining significant representation in positions of high office: Fiji’s Peter Thomson assumed the Presidency of the UN General Assembly in September 2016, [xii] Marlene Moses of Nauru recently concluded her successful chairmanship of the Association of Small Island States (AOSIS), [xiii] Fiji chaired the G77 (+China) from 2012-2014, [xiv] and Samoa hosted the 2014 International Conference of Small Island Developing States. [xv] Such formidable positions within the international community reflect both the Pacific’s rising power and its capability to lead.

More than just a rising global agitator, though, the Pacific’s global significance emanates from its natural wealth. After all, the Pacific is home to a lion’s share of the world’s tuna supply, as well as vast swaths of untapped, underwater mineral deposits such as iron ore, phosphate and oil. Coming into force in 1994, the UN Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS) lent the Pacific greater significance through the delineation of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which stipulates sovereign control over the waters, continental shelf and sea bed within 200 nautical miles (nm) from a state’s coast. [xvi] Such delineation of maritime sovereignty greatly transformed the Pacific islands’ global position; as Modi eloquently stated at the second Forum for India-Pacific Island Cooperation (FIPIC) in 2015 in Jaipur, the Pacific islands are “not small island states but large ocean states with vast potential.” [xvii] As an example of the power of the EEZ, Kiribati is one of the smallest countries in the world by landmass (approximately 811 km2), but its EEZ (approximately 3, 550, 000 km2) makes it a larger state than India. [xviii] Other scholars cite the pooled landmass and EEZ of Pacific island nations to be as large in area as the African continent. [xix] Such characterisations of the Pacific explain to a significant degree the increasing global interest in the island states, and the desire to exert influence in the region.

Pacific partners

The Pacific island states cannot be discussed comprehensively without acknowledging the influence and investment of various partners to the region (both traditional relationships and new linkages). Given that the majority of Pacific island states are dependent on foreign aid, the quality, character and history of key partnerships is crucial in understanding how the islands posture themselves and seek political leverage, despite their dependencies.

Australia and New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand play dominant roles in Pacific relations and have traditionally been regarded as either ‘pseudo-Pacific’ island states or ‘big brothers’ to the region. Their long-standing partnership with the region is based on their stance as two developed powers acting as local hegemon: neighbourhood watchmen, security guarantors, and distributors of aid and disaster relief.

While often forgotten in the contemporary context, Australia and New Zealand’s involvement in the Pacific began through colonisation and, in Queensland’s case, a particularly brutal labour trade. [xx] Australia was the administrating power of New Guinea and Nauru until their independence, and New Zealand had a similar control over Samoa and currently governs Tokelau and partially administers the governments of Niue and the Cook Islands. While Australia and New Zealand have been historically (and contemporarily) characterised as imperial-style powers in the Pacific, New Zealand is much more aligned with Polynesia and self-identifies as a nation of the Pacific. This is in part due to its ethnically Polynesian indigenous population, its geographic location in Polynesia, as well as its leadership role amongst the so-called ‘Polynesian brotherhood’ of Tonga, Samoa, the Cooks Islands, Niue and Tokelau.

Traditional images of Australia and New Zealand in the Pacific, however, have recently been challenged for a variety of reasons. The December 2015 issue of New Pacific Diplomacy of the Australian National University (ANU) authoritatively argues that the Australian and New Zealand-led suspension of Fiji from the PIF in 2009 instigated the emergence of a new diplomatic order in the Pacific, characterised by the estrangement of Australia and New Zealand from the region and the streamlining of Pacific interests. [xxi] Since 2009, Fiji, as the second largest economy in the Pacific (by GDP) and an established regional leader, has been active in organising Pacific-exclusive platforms of engagement, such as the aforementioned PIDF and PSIDS, which deliberately bar Australia and New Zealand. Such behaviour by the Pacific island states reflects a long-held and mounting frustration with the ‘big brothers’ as overbearing regional powers — throwing their weight around within the Forum and taking for granted the Pacific as their territorial backyard or, in former Australian Prime Minister John Howard’s words, “our patch”. [xxii]

While such an estrangement might not be reflected in Australia and New Zealand’s trade and investment portfolio, [xxiii] intimations have been made by Pacific island countries to remove Australia and New Zealand from the PIF due to the diverging interests of the two regional blocs. [xxiv] This is in particular reference to Australia’s notorious resistance to supporting climate change policy, causing Deputy Chief Executive of the Climate Institute Erwin Jackson to infer that Australia was a “low-ambition county” when squared up against the ‘High Ambition Coalition’ at COP21. [xxv]

In sum, while sections of the literature on the Pacific still characterise it as the ‘American Lake’ dominated by the ANZUS (Australia, New Zealand, United States) treaty powers, such a view belongs to a bygone era. While the Australia and New Zealand pact still has significant influence over the region, a changing global order has opened the Pacific not only to other interested Pacific Rim countries, but to leading global powers as well. [xxvi]

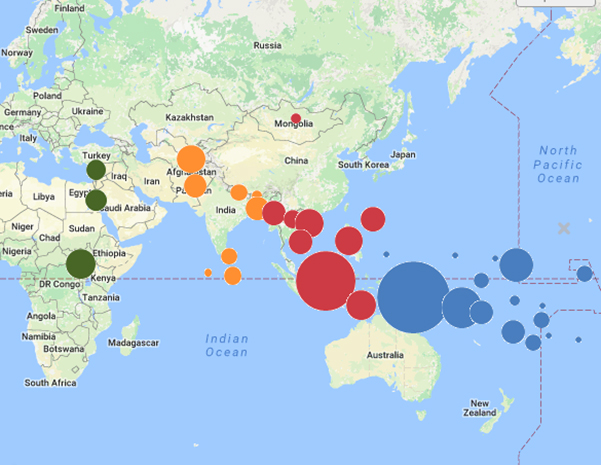

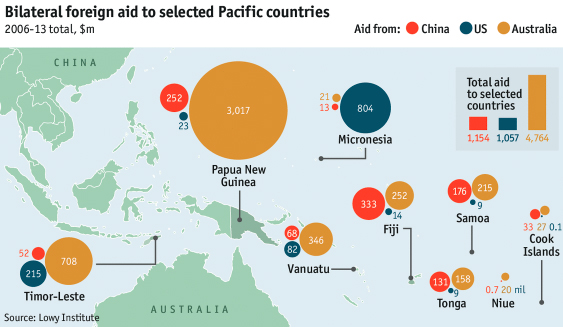

Australian foreign aid distributions

China and Taipei

One of the major themes in Pacific island relations, and arguably another key catalyst of the Pacific’s rearranging diplomatic dynamic, is the rise of China and its increasing involvement in the region. While yet to surpass Australia and New Zealand’s clout (Australia is still the dominant total trade partner and aid donor to the Pacific and, by most judgements, is not likely to be unseated any time soon), [xxviii] China is regarded as the next biggest competitor. Its increasing association with Pacific island states is correlated with its rise as a leading global economy and its keen recognition of the area as being highly strategic. Further, it can be argued that China has been greeted with a warm reception in the Pacific due in part to the Forum Island Countries’ (FICs) aforementioned dissatisfaction with Australia and New Zealand as regional partners. [xxix]

Comparison of Australian, Chinese and US aid to Pacific countries

China’s engagement in the region is typical of its involvement in other parts of the developing world: soft, delayed-interest loans (without Western-style conditionalities for ‘good governance’), gifts to those in power, and bail-outs to defaulting economies. [xxxi] In the Pacific, China has been seen funding large infrastructure projects, such as government buildings, sports fields and educational/cultural precincts, as well as numerous smaller projects, like equipping the Cook Islands’ Members of Parliament with a fleet of quad-bikes, and arranging for a new suite of prime ministerial office quarters for Vanuatu. [xxxii] Chinese aid to the region has also increased significantly, now outperforming Australia as the largest aid contributor to Fiji. Australia is also about to be usurped by China as the largest aid donor to Samoa and Tonga. [xxxiii] Moreover, Chinese migration has increased to the Pacific island countries, along with soft diplomacy measures. In 2014, for example, the Confucius Institute opened at the region’s premier tertiary institution (the University of the South Pacific), to offer language training and education in Chinese culture. [xxxiv]

It is evident that China’s influence in the Pacific (in terms of both hard and soft diplomacy) is multifaceted and widespread, and challenges the development paradigm established by powers like Australia, New Zealand, Japan and the EU. Such ‘western-style’ development policy is characterised by a long-term socio-economic vision. China’s behaviour, on the other hand, is more akin to a ‘cashed-up’ godfather, distributing funds easily and without concern for how it is spent. [xxxv] In the eyes of the Pacific’s long-term development partners, such an approach to the Pacific is both threatening and undermining; not only are promises of (conditional) aid less appealing to Pacific countries, but the careful process of Pacific development is at risk of unravelling in the wake of ready Chinese investment. This is of particular concern to Australia and New Zealand who have long been concerned about ‘failing states’ in the neighbourhood as repositories for drug trafficking, human-trafficking and terrorism. Australia is still implicated in the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI), which stands as Australia’s’ earnest (and long-term) attempt at restoring regional order and good governance in the Pacific. [xxxvi]

Lastly, China’s presence in the Pacific is significant for how it has restructured the region’s diplomatic landscape. Quite simply, now that the FICs have secured another interested and steady global partner, they can begin employing the classic small-state geopolitical strategy of playing larger powers against each other. Historically, the Pacific island states are at their most powerful when they exist in the liminal space of shifting global power dynamics and multi-power orders. When they exist under a hegemony, the Pacific are limited in their ability to bargain and negotiate. The most frequently cited example of such a phenomenon was the Australian ‘containment’ of the Soviet Union in the Cold War Pacific, in some instances quadrupling aid contributions to countries that were liaising too closely with Russian warships, trading and fishing boats. [xxxvii] While China’s presence is undoubtedly democratising the Pacific by widening access to international finance, China’s money is nonetheless being greeted with caution by Pacific island countries, particularly those, like Tonga, Samoa and Vanuatu, who are at risk of suffering ‘debt distress’. [xxxviii]

Taiwan’s role in the Pacific deserves at least a brief mention, given its fierce competition with China in the region against the One China Policy. Of the twenty-one UN member states in the world that recognise Taiwan, six come from the Pacific region: Tuvalu, Nauru, the Solomon Islands, Kiribati, Palau and the Marshall Islands. Some Pacific nations, most notably Kiribati, have been known to swap allegiances between Beijing and Taiwan based on the most lucrative and appealing partnership at the time; yet another example of a small island state using two larger powers to its own advantage. Other than its contest for primacy with China, Taiwan stands as a key East-Asian partner to the Pacific, maintaining amicable diplomatic ties with Pacific island states.

France

France’s position in the Pacific has both historical and contemporary relevance; France was a particularly brutal colonial force in the 19th and 20th centuries, and still retains four Pacific bases in the Pacific Ocean (New Caledonia, French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna, and Clipperton). The French have always retained a strong, albeit under-the-radar, presence in the Pacific, and have mostly been represented though the European Union (EU) as development partners to the region, their respective diplomatic missions within the FICs (Fiji, PNG, Vanuatu), and also through the SPC, of which they were founding members.

The role of the French in the Pacific has recently been pulled into greater focus given the controversial admission of French Polynesia and New Caledonia into the PIF. Such a decision came as a surprise to followers of Pacific regionalism, given that PIF membership has always been reserved for fully self-governing and independent nations. In fact, the PIF has often reiterated in its annual communiques such a position, and granted New Caledonia and French Polynesia observer status, and then associate membership in acknowledgement of their inextricable (and undesirable) connection with metropolitan France. To many, the recently buttressed France within the PIF legitimises the French as a regional power, and precipitates increased regional involvement by the French Republic and its three inhabited territories. While New Caledonia and French Polynesia have always been considered accessories to the region, significant scope now exists for their full incorporation as Pacific island states.

Support for the French in the Pacific comes from Australia and New Zealand which, reportedly, engaged in intense lobbying at the Forum in favour of accepting the French territories as full members. The Prime Minister of France, Manuel Valls, paid strategic visits to Australian and New Zealander Prime Minsters Malcolm Turnball and John Key immediately prior to the last Forum, which further indicates a clear Australia/New Zealand/France grouping within the PIF. [xxxix] This is consistent with the already close defence and security partnership between France, Australia and New Zealand in the Pacific Ocean. Another partnership worth flagging is the humanitarian-based FRANZ alliance in the Pacific, with scope for aid, disaster relief and development assistance. [xl] It is expected that there will be further collaboration between Paris, Canberra and Wellington both within and external to the Forum, particularly as a counterbalance to China’s rising influence in the region.

Other major partners in the Pacific

The Pacific are engaged with many other regional and extra-regional states. The remaining key partners are listed briefly in the following sections.

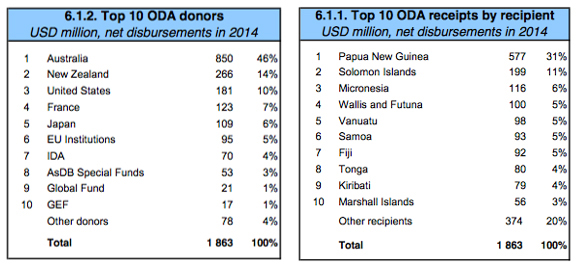

1. Japan has maintained consistent involvement in the Pacific since its occupation of many territories (mainly Micronesia) in the second World War. Its major agency for development is the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which has widespread impact throughout all three regions in the Pacific, maintaining headquarters in nine FICS.[xli] The PIF Secretariat marks Japan as the third largest ODA donor to the region. Japan maintains 10 diplomatic missions within Oceania (including Australia and New Zealand). [xlii]

2. Indonesia is an emerging partner in the Pacific, with particularly strong economic and security links with Australia, Fiji and Papua New Guinea. Importantly, much sensitivity exists within the Pacific region on the issue of West Papua. The Free West Papua campaign claims the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua to be the sovereign land of the resident Melanesians, and also accuses the Indonesian government of subjecting the Melanesians to genocide. The Free West Papua campaign has created considerable tension between Pacific island nations and Indonesia, and sits as an unresolved issue within the PIF. [xliii]

3. The European Union (EU) are most active through the European Development Fund (EDF11). The EU administer the Regional Indicative Program (RIP) which strives for the realisation of development goals within the Pacific. The EDF RIP commits 166 million Euro to the Pacific for the 2014-2020 period. [xliv]

4. The United States of America (USA) is still, unquestionably, the dominant maritime power of the Pacific, with numerous military bases in the northern Pacific, as well as in Japan (Okinawa, Kanagawa [Sasebo]) and Australia (Darwin). It administers the colonial territories of Guam and American Samoa, and maintains a close relationship with the Micronesia states of ‘compact association’ — Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), and the Marshall Islands. Its ODA contribution to Pacific is minimal, aside from its contributions to the compact states. [xlv] Importantly, then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton attended the 2012 post-forum dialogue in the Cook Islands (Rarotonga), reiterating the Pacific’s importance to America. Clinton concluded her visit by donating an additional US$32 million for sustainable development programmes. [xlvi]

Figures 4 & 5: Main ODA Donors and Recipients in the Pacific, minus China.

India in the Pacific

Within the context of both key Pacific regional dynamics, as well as major Pacific partnerships, it is pertinent to examine India’s involvement in the region.

Indian Diaspora in Fiji

Historically, India’s entrance into the Pacific Ocean was through neither conquest nor trade, but by the colonial system of indentured labour. Between 1879 and 1916 (when indentured labour was abolished), approximately 60,000 Indians were brought to Fiji to work on sugar plantations to fuel the British colonial economy. [xlviii] Whilst some of the labourers returned home at the end of their contracts, a greater portion decided to settle in Fiji given that their repatriation to India would be at their own expense. The exploitation of the ‘girmityas’ (indentured labourers) was rife and their wages were low (if at all given), so the decision to settle in Fiji was often a necessity. [xlix] In the ensuing years, the descendants of the girmityas came to form the largest minority population within the islands and now claim a unique ‘Indo-Fijian’ identity. Indo-Fijians are one of India’s most dominant diaspora populations; in 2016, approximately 38 percent of Fiji’s population were of Indian origin, which has decreased from the 45-47 percent Indo-Fijian population of earlier years. [l]

Throughout Fiji’s history, significant tensions have existed between the indigenous Fijians (Itaukei) and the Indo-Fijians, with the Indian population being branded in the past as vulagi (foreigners) and regarded as a threat to the sovereignty of the Itaukei. To be sure, ethnic tensions have eased by 2016 (relative to the chaotic earlier era of the coup d’etats of 1987 and 2000) and Indo-Fijians now enjoy the rights to citizenship and political representation, although not the rights to ownership of native land. There is still, however, a significant cultural divide between the Itaukei and Indo-Fijians in language, industry, custom, and marriage. [li]

The Indian diaspora in the Pacific, and particularly in Fiji, has been of key interest to India though, until recently, India has had little involvement with the Indo-Fijians. Apart from a brief visit by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1981, India has maintained relations with Fiji from afar, and sometimes barely had any relations at all, particularly around the time of 1989 when thousands of Indo-Fijians were migrating away from Fiji out of fear of racial persecution. [lii] Jha marks 1991 as the year in which relations between India and Fiji were “completely severed” when the Fijian parliament made it unconstitutional for Indo-Fijians to form a majority political party within parliament. [liii]

Contemporary relations between India and Pacific Island states

Tense histories aside, India-Fiji and India-Pacific relations have entered a period of recovery and acceleration, particularly under the administration of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and also with Fiji’s return to democracy in 2014. During Laisenia Qarase’s prime ministership (2000-2006), Fiji supported India’s (and Japan’s) bid for permanent membership to the UN Security Council [liv], and in 2006, India became a post-Forum dialogue partner at the annual PIF. [lv]

In 2014, Modi became the first prime minister to visit Fiji since Gandhi’s visit in 1981, holding bilateral discussions with Fiji’s Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama. [lvi] During this visit to Suva, Modi also met with 12 other Pacific island leaders in the first Forum for India-Pacific Island Cooperation (FIPIC). Modi hosted the second FIPIC in Jaipur in 2015 with all 14 Pacific island leaders in attendance, where the major themes were sustainable blue-water economies, the bolstering of renewable energy industries, as well as climate change adaptation and resilience for Pacific island communities. India committed to doubling aid contributions to all Pacific island nations (an increase from US$100,000 to $200,000 from 2006-2014), [lvii] as well as creating further scope for various other areas of joint cooperation, such as a ‘Pan Pacific islands e-network’, Indian navy hydrological surveys in the region, disaster-relief cooperation, and a space technology partnership. India has also proposed to assist in the training of diplomats from the Pacific, and expressed interest in collaborating on oil and natural gas mining research in the Pacific.

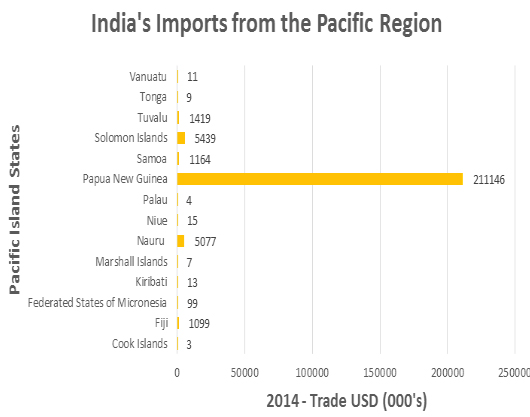

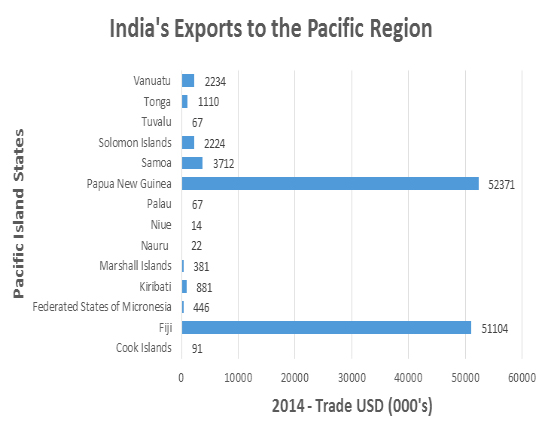

The recent articulation of the India-Pacific island partnership appears broad and far-reaching, but in reality, most of the suggestions for cooperation remain gestures of amity rather than realised joint operations. In fact, Modi’s suggestion at the 2015 FIPIC in Jaipur to organise in New Delhi in 2016 an international conference on Pacific island states and the blue water economy has yet to happen, which arguably is leading some to wonder about a stalling momentum in India-Pacific islands relations. [lviii] Should Modi and the Pacific islands build upon their warm exchanges at the FIPIC in Suva and Jaipur and engage in all of the proposed ventures, India would still be regarded as a minor partner to the region, with minimal economic or diplomatic ties binding the regions together. As it stands, India has only four diplomatic missions in the entire Pacific region (Australia, New Zealand, Fiji and Papua New Guinea), and India’s trade portfolio is mostly limited to exports to PNG and Fiji, and imports from PNG (PNG and Fiji being the Pacific’s two largest economies). [lix]

India’s Imports from the Pacific Region

India’s Exports to the Pacific Region

Importantly, the India-Pacific partnership needs to be viewed relative to the myriad other partners to the region, as India’s role in the region is, comparatively, infant, timid and not well-defined.

Articulating a Closer Relationship for India and the Pacific

India is well placed to act as a more serious stakeholder in Pacific affairs, and to engage the Pacific island countries in a more meaningful manner. While of course India’s entrance into Pacific relations is relatively recent and the relationship perhaps needs more time to mature, Modi can still add more structure and direction to arguably amorphous pledges to engage.

Differentiating between the ‘Pacific islands’ and the ‘Pacific partners’

One of the first recommendations for Modi in achieving a more streamlined approach to India-Pacific islands relations is to differentiate his foreign policy between the Pacific island states and the ‘Pacific Partners’. The term ‘Pacific Partners’, in this instance, refers to Australia, New Zealand and France as the major (and traditional) stakeholders in the region.

Australia and New Zealand

As alluded to earlier, the Pacific island states and the FICs are, at present, consciously pulling away from their ties with Australia and New Zealand and moving toward a more Pacific-first policy. Such a phenomenon has been noted quite extensively in the media and in authoritative academic sources, with the vanguard work, The New Pacific Diplomacy, noting a new era in Pacific island relations.

India should be careful to avoid engaging the Pacific islands through the lens of a multilateral partnership with Australia and New Zealand which, arguably, could restrict their movement in the region. Based on the rhetoric of Pacific island leaders like Fiji, [lxii] a direct association with Australia and New Zealand might not be received favourably by the Pacific island states, which are firmly insisting on forging relationships on their own terms, and outside of the Australia-New Zealand paradigm. The Pacific-only FIPIC was a strategically sound step for Modi and it is suggested that Modi continue such a Pacific-focused approach to the island states.

The French Republic

Perhaps of greater concern to India’s good relationship with the island states is the India-France partnership which has been widely acclaimed for its warmth, flattery and comprehensive strategy. [lxiii] While French-Indian collaboration in the Indian Ocean has been sealed through joint statements on counter-terrorism, defence and security, a bilateral strategy has yet to be articulated in the context of the Pacific Ocean.

Some could argue that the time is ripe for India and France to propagate the close Indian Ocean-style relationship into the Pacific region; the recent PIF decision to incorporate two French territories as full members herald the French Republic as a legitimate and rising power in Pacific regionalism. For India, the four French bases in the Pacific could represent well-placed stepping stones across the Pacific Ocean, which could be a welcome foothold into an otherwise unfamiliar region. Moreover, the French hold influential seats within the EU outfit in the Pacific as well as the long-established SPC (also known as Pacific Community). As one of the largest maritime powers of the globe, and boasting the second largest EEZ, France has a concerted stake in the Pacific Ocean as the next frontier of marine research and marine management.

This paper argues, however, that India should instead act with caution before aligning with the French, given the long (and ongoing) history of French colonialism in the Pacific. Aside from its exploits as a particularly brutal 19th and 20th-century imperial force, France’s political aspirations in the Pacific are still encumbered by Kanak-led independence movements in New Caledonia and, to a certain extent, in French Polynesia. Both French Polynesia and New Caledonia are inscribed on the UN decolonisation list, [lxiv] and New Caledonia anticipates in 2018 a long-awaited referendum for independence from metropolitan France. [lxv]

The PIF decision to incorporate the two French territories as full members departs from the Forum’s founding premise that membership is to be reserved for independent and fully-self-governing nations of the Pacific. While evidently, there was enough support within the Forum for the PIF’s apparently unanimous decision to discard its criteria and accept the French territories, it can be argued that such a welcome by the Pacific Island states is a welcome in theory but not necessarily in practice. [lxvi] While the dust is still settling on the latest round of PIF mandates, it is likely the PIF will, at least initially, place the newly buttressed French into the category of ‘others’, alongside Australia and New Zealand. Such an in-house characterisation of the French is even more likely given the aforementioned closeness of partnership between Australia, New Zealand and the French Republic.

It is recommended that India continue to engage the Pacific in a Pacific-specific manner, and maintain the desirable position as a non-aligned actor. While of course Indian relations with France, Australia and New Zealand are integral to their global agenda, India would do well to avoid presenting themselves to the Pacific as one of the ‘Pacific Partners’; a two-pronged approach to the Pacific Islands and Pacific Partners will ensure that India retains the advantage of neutrality with the island states whilst also furthering long-held partnerships with Australia, New Zealand and France.

Which Pacific Island States should be targeted?

The next step in streamlining Modi’s Pacific partnerships involves identifying which Pacific island countries should be engaged specifically, in order to maximise India’s capital and influence within the region. The suggestion to target particular islands is not intended to discount Modi’s whole-region approach reflected by FIPIC, but rather a suggestion that strategic bilateral relationships should be pursued alongside holistic regional engagement.

Fiji and PNG

As seen through Modi’s bilateral visit to Suva in 2014, and Indian President Pranab Mukherjee’s official visit to Port Moresby in 2016, the current Indian administration evidently has a strong interest in furthering partnerships with Fiji and PNG as the two largest economies within the region. [lxvii] The latest trade flow data between India, Fiji and PNG suggest that economic linkages are on the rise, with key exports to the Pacific being pharmaceuticals and textiles, with the Pacific mostly exporting iron ore, phosphate, gold and timber. [lxviii] While the Pacific are limited in their export capacity, there is significant scope for India’s trade profile to broaden in Fiji and PNG, for instance, by exporting speciality, low-cost items such IT products and services.

Another key area of opportunity for India’s engagement is through capacity building. The Pacific face some of the most common developmental challenges of small island states — most notably, aid-dependent economies, limited onshore resources, a vulnerability to natural disasters, as well as a raft of other socio-economic barriers. Pacific communities are small and there is, quite simply, a reduced ability to develop national expertise. The Pacific countries often elect to channel their internal resources into developing niche areas of expertise (such as climate change diplomacy and fisheries management) and reach out to their partners for capacity building in other areas of statecraft.

At the time of writing, a delegation from Fiji, as well as personnel from Fiji’s High Commission in New Delhi, are meeting with leading think tanks in New Delhi in consultation on matters of Pacific security and maritime surveillance. It is reported that Fiji is moving to draft its first white paper, and their movements in New Delhi suggest that Fiji views India as a prospective partner to assist in the formulation of its defence strategy. Nothing yet has been reported to confirm a Fiji-India collaboration in this regard, but it goes without saying that this presents a prime opportunity for India to deepen ties with Fiji’s Ministry of Defence. This possible joint venture should be taken as a valuable example of how India can target its own strengths toward Pacific island capacity building. In addition to collaborating with the Pacific on matters of defence, India could also market themselves as partners in information technology (IT) connectivity in the islands, as well as training in peacekeeping exercises and military organisation. Significantly, India should not dismiss such outreach by the island states and take further initiative in instigating capacity building ventures.

It is also worth briefly covering the Indian diaspora in Fiji, and to question its value as a point of engagement between India and Fiji. Modi’s foreign policy places a strong emphasis on India’s diaspora links, but it can be argued that Indo-Fijians have been relatively neglected throughout their history of settlement, and are consequently less loyal than other diaspora populations around the world, particularly recent migrants. [lxix] It has been argued by some that a strong focus by Modi on the Fijian diaspora might alienate other Pacific Islands with fewer cultural links to India. [lxx] Given the various other points of cooperation between India and the Pacific, as well as myriad other prospective ventures, perhaps it is enough to state that India does not need to emphasise the diaspora in Fiji and should instead view this historic link as merely a complement rather than a founding block for regional engagement.

Polynesia

The suggestion for India to enhance relations with PNG and Fiji is an obvious one, but perhaps less obvious is the idea to look beyond Suva and Port Moresby, and to not confuse these countries as the only Pacific powerhouses. Undoubtedly, Melanesia does serve as a kind of gateway between the deeper Pacific and the wider world. Fiji and PNG boast: the largest share of the region’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP); more than three-quarters of the entire population of the Pacific (PNG approximately eight million, Fiji approximately one million); the largest landmasses (PNG is largest, Fiji is 3rd largest); and the greatest number of diplomatic ties, connections and missions abroad.

Despite Melanesia’s relative wealth and higher capacity to participate in the international community, it can be argued that India should also pursue more unlikely relationships in the Pacific, in the interest of developing relations with equally important, but more neglected corners of the ocean. This is with particular reference to Polynesia, which arguably stands as the most insulated subsection of the Pacific region. Unlike Micronesia, which is still firmly within the economic, bureaucratic and military grasp of the United States, Polynesia is relatively unaligned and available for new partnerships. Aside from Australia’s overarching influence, New Zealand, and now China, stand as the major partners to Polynesia, with New Zealand sitting as perhaps the power with the most political capital. A suggestion for India is to engage New Zealand with a mind to further ties with Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu and, to a lesser extent, the Cook Islands. Recent reports signal there is a great lack of trade competition in Tonga and Samoa, with most markets dominated by high-cost Chinese and Japanese imports. [lxxi] There is wide scope for India to open up trade routes with Tonga and Samoa, and to engage in a manner similar to Fiji and PNG, as laid out above.

India could also suggest a dialogue partnership with the PLG. Given that the PLG liaise with the likes of American Samoa and even Easter Island as Polynesian entities, India could find many new opportunities to increase their exposure to eastern Pacific Rim countries.

Small Island States

India should also realise Small Island States (SIS) as an emerging Pacific (and global) identity which has come to lobby within the UN under the ad-hoc grouping of SIDS (Small Island Developing States). Much of the same advice listed earlier applies to India and the SIS — while seemingly insignificant in terms of economic weight or hard political power, the SIS are a growing voice in multilateral fora and command moral weight and momentum. The SIS in the Pacific have begun meeting separately from the all-member PIF structure, in recognition of the unique challenges and abilities of Pacific SIS. [lxxii] Looking now to the global scale, India should take notice of Sweden’s example of collaborating with Fiji to organise the UN Conference on Oceans. [lxxiii] India should present itself to the SIS as a prospective partner for various projects, whether it be the organisation of conferences, support at the UN, or development projects.

Faultlines in Pacific regionalism

By way of concluding this ‘Guidebook on Pacific Diplomacy’, it is appropriate to flag some faultlines within the region, and the PIF, which are likely to influence diplomatic dynamics within the region. India should keep abreast of the topics mentioned in the following sections, in the interest of maintaining a high literacy in Pacific affairs.

West Papua

Currently, the issue of West Papua is a significant source of tension within the Pacific. The Free West Papua campaign has rising influence and popularity in the Pacific and the wider world, and are calling for the recognition of the rights to self-determination of the Melanesians resident in the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua (formerly Irian Jaya and West Irian Jaya). The Free West Papua Campaign claims that indigenous West Papuans are experiencing a slow genocide in the hands of the Indonesian government. While the PIF have expressed concern at alleged human rights abuses against Melanesians in Indonesia, they have consistently recognised the sovereignty of Indonesia over former West Guinea. [lxxiv]

The Forum’s lack of progress and activism on West Papua is a key source of frustration within Pacific communities and also within a selection of members within the Forum. At the last UN General Assembly (71st), seven leaders of Pacific countries raised their concerns about the plight of Indonesian West Papuans. These countries were the Solomon Islands, the Marshall Islands, Vanuatu, Tuvalu, Tonga, Palau and Nauru. Significantly, the prime ministers of the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Tuvalu broke with tradition by associating human rights abuses in West Papua to the Melanesian’s inherent rights to self-determination and sovereignty. [lxxv] Another recent development worth mentioning is the likely acceptance into the MSG of the amalgam resistance group and political entity, the ULMWP (United Liberation Movement for West Papua). It was reported in October that Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands and the FLNKS (Front de Liberation Nationale Kanak et Socialiste) were moving to incorporate the ULMWP into the MSG despite reluctance from Fiji and PNG as the remaining two members. [lxxvi]

For India, it is important to note that West Papua is a current wedge within the region (in both the PIF and the MSG), with many differences of opinion rendering the regional forums inert by internal stalemate. For the PIF, maintaining good relations with Indonesia is of utmost importance. Australia, Fiji and PNG particularly have strong economic and defence partnerships with Indonesia and, based on their behaviour within both the PIF and MSG, are unwilling to compromise such a relationship by advocating for the sovereignty of indigenous West Papuans.

PIF Membership

Another point of confusion, or uncertainty, within the PIF is their criteria for membership, which was recently abrogated by the inclusion of French Polynesia and New Caledonia at the 47th annual Forum in Pohnpei. [lxxvii] PIF membership has always been restricted to fully self-governing independent nations, with Observer and Associate Member criteria deliberately designed for invested non-self-governing island groups, like New Caledonia and French Polynesia, to participate in Forum events. Aside from opening a kind of Pandora’s box — inclusion of the French territories encourages other non-sovereign nations like American Samoa, Guam and Tokelau — this recent Forum decision also sits at odds with the PIF’s historic support for decolonisation. The PIF even supported the inscription of New Caledonia and French Polynesia on the UN’s decolonisation list (Committee 24). [lxxviii]

The confusing membership decision, as well as the aforementioned tension on West Papua, hints at a larger discrepancy within the PIF — their collective stance on decolonisation. In the space of a few series of annual PIF mandates, the regional Forum has apparently retreated from its historic identity as a champion for independence and self-determination of Pacific islanders.

It remains unclear how French Polynesia and New Caledonia will be welcomed into the Forum. It is fair to observe, though, and important for India to note that the PIF is undergoing a troubled period and have morphed into an organisation that arguably resembles the former SPC: the first regional forum of the Pacific which was predominantly managed by the imperial powers, and which inspired the formation of the independent PIF. While the PIF is still undoubtedly the premier political body of the Pacific and is unlikely to lose its function in the short term, [lxxix] some have indicated that the Pacific voice within the PIF is being diluted by the demands of Australia and New Zealand (and now perhaps France), thus rousing reflections on PIF’s split from the SPC in 1971.

Sub-regionalism

Related to the changing political dynamics within the PIF is the rise of sub-regional identities within the Pacific. This paper has already discussed the rise of the MSG and PLG as examples of diverging and strengthening ethnic and political characters within the region. Whether this phenomenon serves as a complement or a threat to regionalism has not yet been settled by the literature, and it appears that professionals in the field are currently trying to accommodate sub-regional initiatives while still preserving the integrity and legitimacy of the whole-region Forum.

Based on the dynamic and sensitive nature of these regional faultlines, India is advised to remain up-to-date on regional affairs and to remember that bilateral and sub-regional engagement is perhaps their best strategy and asset in the region. While it is unlikely that the PIF will fall from its position as the premier forum for regional conversation and cooperation, [lxxx] it is important for India to understand that the PIF should not be their sole source of contact with the Pacific. To develop a comprehensive, intelligent and long-lasting Pacific strategy, India should understand the relevance of all the individual actors and appreciate their unique identities and abilities.

Conclusion

This paper has given a comprehensive background to Pacific affairs and India’s relationship with the region. It was suggested that India continue engaging with the Pacific in a Pacific-specific manner and to ensure that it retains its advantage of being a relatively neutral partner. While India’s heightened involvement with Fiji and PNG is of course advisable, India should also engage with all the Pacific island states in order to broaden its influence within the region. India can increase trade to the region and support capacity building measures. While there are many active partners in the region, Polynesia is more available for a comprehensive partnership with India, given its insulation in the Pacific and its relative lack of competition. The Pacific is a rapidly changing landscape, and India must remain abreast of particular faultlines in its regional architecture. Knowledge of key points of tension will help India avoid making diplomatic blunders, while also demonstrating a higher-than-normal literacy in Pacific affairs — a literacy very much lacking in many international partners.

Endnotes

[i] Wellington. Pacific Islands Forum, Official Communique 1971, http://www.forumsec.org/resources/uploads/attachments/documents/1971%20Communique-Wellington%205-7%20Aug.pdf.

[ii] Man Mohini Kaul, Pearls in the Ocean: Security Perspectives in the South-West Pacific (New Delhi: UBSPD Publishers, 1993).

[iii] Darryn Webb, “China’s South Pacific Expansion and the Changing Regional Order: A Cause for Concern to the Regional Status Quo?,” Australian Defence College, Centre for Defence and Strategic Studies, 2015, http://www.defence.gov.au/ADC/Publications/IndoPac/Webb_IPS_Paper.pdf.

[iv]Pohnpei. Pacific Islands Forum, Official Communique 2016, http://www.forumsec.org/resources/uploads/embeds/file/2016_Communique_FINAL_web.pdf.

[v] Greg Fry and Sandra Tarte, “Introduction,” in The ‘New Pacific Diplomacy,’ ed. Grey Fry and Sandra Tarte (Canberra: ANU Press, 2016), 6.

[vi] Fulori Manoa, “The New Pacific Diplomacy at the United Nations: The rise of the PSIDS,” in The ‘New Pacific Diplomacy’, ed. Grey Fry and Sandra Tarte (Canberra: ANU Press, 2016), 89; H.E President Anote Tong, “Charting its Own Course’: A Paradigm Shift in Pacific Diplomacy,” in The ‘New Pacific Diplomacy’, 22.

[vii] Niranjan Chandrashekhar Oak, “South Pacific: Gaining Prominence in Indian Foreign Policy Calculations,”(Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, May 10, 2016), http://www.idsa.in/backgrounder/south-pacific-and-indian-foreign-policy_noak_100516.

[viii] Manoa, The ‘New Pacific Diplomacy’, 89.

[ix] Nicollette Goulding, “Marshalling a Pacific Response to Climate Change,” in The ‘New Pacific Diplomacy,’ 191.

[x] Sara Phillips, “Paris Climate Deal: How a 1.5 Degree Target Overcame the Odds at COP21,” ABC News, December 13, 2015, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-12-13/how-the-1-5-degree-target-overcame-the-odds-in-paris/7024006.

[xi] Dame Meg Taylor, “Pacific Regionalism” (Keynote Address Presented at the Australian Council for International Developments National Conference, Melbourne, October 26-27, 2016), http://www.forumsec.org/pages.cfm/newsroom/speeches/2016-1/secretary-general-dame-meg-taylors-keynote-address-at-australian-council-for-international-development-acfid-national-conference-melbourne-26th-october-2016.html.

[xii] United Nations. “Peter Thomson of Fiji President of Seventy-First General Assembly,” September 13, 2016, http://www.un.org/press/en/2016/ga11816.doc.htm.

[xiii] The Alliance of Small Island States, last updated 2015, http://aosis.org/about/.

[xiv] Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme, “Fiji, Chair of G77- “We, as Small Islands Can Do This,” November 19, 2013, http://www.sprep.org/climate-change/fiji-chair-of-g77-qwe-as-small-islands-can-do-thisq.

[xv] Manoa, The ‘New Pacific Diplomacy’, 89.

[xvi] United Nations. “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea,” http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.

[xvii] Narendra Modi, “Welcome Speech” (Opening Remarks at Forum For India Pacific Island Countries (FIPIC) Summit, Jaipur, August 21, 2015), http://www.narendramodi.in/pm-s-opening-remarks-at-forum-for-india-pacific-island-countries-fipic-summit-jaipur-282251.

[xviii] Pacific Community, “Kiribati,” https://www.spc.int/climate-change/fisheries/assessment/chapters/summary/8-kiribati.pdf

[xix] Fry and Tarte, “Introduction,” in The ‘New Pacific Diplomacy,’ 5.

[xx] Ian C. Campbell, “Melanesia: Sandalwood and ‘Blackbirding’,” in A History of the Pacific Islands (USA: University of California Press, 1990), 101, 115.

[xxi] Fry and Tarte, “Introduction,” in The ‘New Pacific Diplomacy,’ 12.

[xxii] Joanna McCarthy, “China Extends its Influence in the South Pacific,” ABC News, September 10, 2016, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-09-10/china-extends-its-influence-in-the-south-pacific/7812922; Sandra Tarte, “Australia and the Pacific Islands: A Loss of Focus or a Loss of Direction?” East Asia Forum, April 29, 2011, http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2011/04/29/australia-and-the-pacific-islands-a-loss-of-focus-or-a-loss-of-direction/.

[xxiii] Australia. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. “Aid Investment Plan: Pacific Regional 2015-16 to 2018-19,” http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/pacific-regional-aid-investment-plan-2015-19.pdf; New Zealand. Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. “New Zealand Aid Programme Strategic Plan 2015-2019,” https://www.mfat.govt.nz/assets/_securedfiles/Aid-Prog-docs/ASEAN/New-Zealand-Aid-Programme-Strategic-Plan-2015-19.pdf.

[xxiv] Rowan Callick, “Fiji Wants Australia out of Pacific Islands Forum,” The Australian, April 6, 2015, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/foreign-affairs/fiji-wants-australia-out-of-pacific-islands-forum/news-story/5f1551ee2361b0bce27c2c997502d286

[xxv] Tom Arup and Adam Morton, “Australia Snubbed by “High Ambition” Group at Climate Talks in New York,” The Sydney Morning Herald, April 22, 2016, http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/australia-snubbed-by-highambition-group-at-climate-talks-in-new-york-20160421-gobk58.html.

[xxvi] Fry and Tarte, “Introduction,” in The ‘New Pacific Diplomacy,’ 6.

[xxvii] Australia. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Where We Give Aid,” last updated 2016, http://dfat.gov.au/aid/where-we-give-aid/pages/where-we-give-aid.aspx.

[xxviii] Lowy Institute for International Policy, “Chinese Aid in the Pacific,” http://www.lowyinstitute.org/chinese-aid-map/; Lowy Institute for International Policy, “Australian Aid,” November 6, 2016, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/issues/australian-foreign-aid.

[xxix] Fry and Tarte, “Introduction,” in The ‘New Pacific Diplomacy,’ 12.

[xxx] The Economist, “Big Fish in a Big Pond,” March 25, 2015, http://www.economist.com/news/asia/21647169-chinese-aid-region-expandingas-its-immigrant-community-big-fish-big-pond.

[xxxi]McCarthy, “China Extends its Influence in the South Pacific,” ABC News, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-09-10/china-extends-its-influence-in-the-south-pacific/7812922.

[xxxii]McCarthy, “China Extends its Influence in the South Pacific,” ABC News, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-09-10/china-extends-its-influence-in-the-south-pacific/7812922; Radio New Zealand, “China to fund renovation of Vanuatu PM’s Offices,” May 16, 2016, http://www.radionz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/304024/china-to-fund-renovation-of-vanuatu-pm’s-offices.

[xxxiii]McCarthy, “China Extends its Influence in the South Pacific,” ABC News, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-09-10/china-extends-its-influence-in-the-south-pacific/7812922.

[xxxiv] The University of the South Pacific, “Confucius Institute at the University of the South Pacific,” https://www.usp.ac.fj/index.php?id=10988.

[xxxv] McCarthy, “China Extends its Influence in the South Pacific,” ABC News, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-09-10/china-extends-its-influence-in-the-south-pacific/7812922.

[xxxvi] Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands, http://www.ramsi.org.

[xxxvii] Greg Fry, “The Politics of South Pacific Regional Cooperation,” in The South Pacific: Problems, Issues and Prospects, ed. Ramesh Thakur (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), 176.

[xxxviii] McCarthy, “China Extends its Influence in the South Pacific,” ABC News, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-09-10/china-extends-its-influence-in-the-south-pacific/781292.

[xxxix] Paul Soyez, “French Presence in the Pacific Reinforced by the PIF,” The Strategist (The Australian Strategic Policy Institute), September 28, 2016, http://www.aspistrategist.org.au/french-presence-pacific-reinforced-pif/.

[xl] New Zealand. Mistry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “The FRANZ Agreement,” https://www.mfat.govt.nz/assets/_securedfiles/Aid-Prog-docs/Franz-Arrangement-Brochure.pdf.

[xli] Japan International Cooperation Agency, https://www.jica.go.jp/english/.

[xlii] Pacific Island Forum Secretariat, “Japan Fact Sheet,” last updated 2016, http://www.forumsec.org/pages.cfm/strategic-partnerships-coordination/post-forum-dialogue/japan.html.

[xliii] Pohnpei. Pacific Islands Forum, Official Communique 2016, http://www.forumsec.org/resources/uploads/embeds/file/2016_Communique_FINAL_web.pdf.

[xliv] Pacific Island Forum Secretariat, “European Union Fact Sheet,” last updated 2016, http://www.forumsec.org/pages.cfm/strategic-partnerships-coordination/post-forum-dialogue/european-union-1.html.

[xlv] Pacific Island Forum Secretariat, “United States of America Fact Sheet,” last updated 2016, http://www.forumsec.org/pages.cfm/strategic-partnerships-coordination/post-forum-dialogue/united-states.html.

[xlvi] Hilary Clinton, Remarks at the Pacific Island Forum Post-Forum Dialogue, Rarotonga, August 31, 2012, http://www.state.gov/secretary/20092013clinton/rm/2012/08/197266.htm.

[xlvii] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Development Aid at a Glance- Statistics by Region: Oceania, 2016,”http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/documentupload/6%20Oceania-%20Development%20Aid%20at%20a%20Glance%202016.pdf.

[xlviii] Pankaj K. Jha, India and the Oceania: Exploring Vistas for Cooperation (New Delhi: Pentagon Press, 2016), 114.

[xlix] Ibid.

[l] Ibid.

[li] Jha, India and the Oceania, 115.

[lii] Ibid., 183.

[liii] Ibid., 183.

[liv] Statement during the high-level plenary meeting of the 60th session of the United Nations General Assembly, Speech of Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase, September 16, 2005. Available at: www.un.org/webcast/summit2005/statements16/fiji050916eng.pdf.

[lv] Ibid., 183.

[lvi] Narendra Modi reaches Fiji, first visit by an Indian PM in 33 years,” The Times of India, November 19, 2014, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Narendra-Modi-reaches-Fiji-first-visit-by-an-Indian-PM-in-33-years/articleshow/45196980.cms.

[lvii] Pacific Island Forum Secretariat, “India Fact Sheet,” last updated 2016, http://www.forumsec.org/pages.cfm/strategic-partnerships-coordination/post-forum-dialogue/india.html.

[lviii] Patrick Walsh, “India’s Pivot to Oceania: Modi and the Pacific Island Nations,” The Diplomat, September 20, 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2016/09/indias-pivot-to-oceania-modi-and-the-pacific-island-nations/.

[lix] Pacific Island Forum Secretariat, “India Fact Sheet,” last updated 2016, http://www.forumsec.org/pages.cfm/strategic-partnerships-coordination/post-forum-dialogue/india.html.

[lx] Ibid.

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Rowan Callick,“Fiji Wants Australia Out of the Pacific Islands Forum,” The Australian, April 6, 2015, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/foreign-affairs/fiji-wants-australia-out-of-pacific-islands-forum/news-story/5f1551ee2361b0bce27c2c997502d286.

[lxiii] Patrick Walsh, “India, France and the Pacific: Where Old Friends Might Get in the Way of New Partnerships,” The Lowy Institute of International Policy, October 19, 2016, https://www.lowyinterpreter.org/the-interpreter/india-france-and-pacific-where-old-friend-might-get-way-new-partnerships.

[lxiv] The United Nations and Decolonisation, “Non Self-governing Territories, “http://www.un.org/en/decolonization/nonselfgovterritories.shtml.

[lxv] “New Caledonia Profile,” BBC News, June 16, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-16740838.

[lxvi] Barbara Dreaver,“Fiji PM’s Boycott of the Pacific Islands Forum was Perfect Timing,” Radio New Zealand, September 10, 2016, https://www.tvnz.co.nz/one-news/new-zealand/opinion-fiji-pms-boycott-pacific-islands-forum-perfect-timing.

[lxvii]Indian Ministry of External Affairs, “India-Papua New Guinea Joint Statement During the State Visit of President to Papua New Guinea,” April 29, 2016, http://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/26717/India+Papua+New+Guinea+Joint+Statement+during+the+State+Visit+of+President+to+Papua+New+Guinea.

[lxviii] Pacific Island Forum Secretariat, “India Fact Sheet,” last updated 2016, http://www.forumsec.org/pages.cfm/strategic-partnerships-coordination/post-forum-dialogue/india.html.

[lxix] Balaji Chandramohan, “Political Crisis in Fiji and India’s Concerns,” (Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, August 19, 2010), http://www.idsa.in/idsacomments/PoliticalCrisisinFijiandIndiasConcerns_bchandramohan_190810.

[lxx] Tevita Motulalo, “India’s Strategic Imperative in the South Pacific,” (Gateway House- Indian Council on Global Relations, October, 2013, p22), http://www.gatewayhouse.in/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Indias-Strategic-Imperative-in-the-South-Pacific.pdf.

[lxxi] McCarthy, “China Extends its Influence in the South Pacific,” ABC News, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-09-10/china-extends-its-influence-in-the-south-pacific/7812922.

[lxxii] “FSM Joins Smaller Islands States of the Pacific Islands Forum,” Pacific Islands Report, September 9, 2016, http://www.pireport.org/articles/2016/09/08/fsm-joins-smaller-islands-states-pacific-islands-forum.

[lxxiii] “Fiji and Sweden to Host Oceans Conference,” Radio New Zealand News, October 5, 2015, http://www.radionz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/286098/fiji-and-sweden-to-host-oceans-conference.

[lxxiv] Pohnpei. Pacific Islands Forum, Official Communique 2016, http://www.forumsec.org/resources/uploads/embeds/file/2016_Communique_FINAL_web.pdf.

[lxxv] “Pacific Leaders to Take Papua up at UN,” Radio New Zealand News, September 15, 2016, http://www.radionz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/313397/pacific-leaders-to-take-papua-up-at-un.

[lxxvi] “West Papua to Join MSG,” Fiji Times, October 11, 2016, http://www.fijitimes.com.fj/story.aspx?id=374239.

[lxxvii] Pohnpei. Pacific Islands Forum, Official Communique 2016, http://www.forumsec.org/resources/uploads/embeds/file/2016_Communique_FINAL_web.pdf.

[lxxviii] Nic Maclellan, “Pacific Diplomacy and Decolonisation in the 21st Century,” in The ‘New Pacific Diplomacy,’ ed. Grey Fry and Sandra Tarte (Canberra: ANU Press, 2016), 266.

[lxxix] Bruce Hill, “Removal of Australia & NZ from PIF Unlikely Says Academic,” ABC News, September 14, 2015, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-09-11/removal-of-australia–nz-from-pif-unlikely-says/6772748.

[lxxx] “New Study: Pacific Island Forum Still Relevant and Effective,” Pacific Islands Report, November 6, 2016, http://www.pireport.org/articles/2016/11/06/new-study-pacific-island-forum-still-relevant-and-effective.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Patrick Walsh was a visiting Australian researcher at Observer Research Foundation (ORF). He studies at the University of Queensland, and came to New Delhi in ...

Read More +