-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

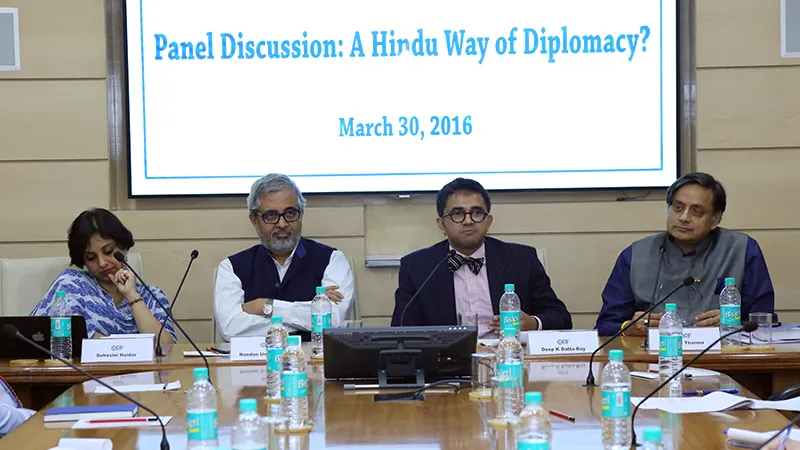

The author of “The Making of Indian Diplomacy”, Mr. Deep K. Dutta Ray, has said that his book’s purpose was to eke out the rationale behind Indian diplomacy, and not propose course corrections. He was speaking at a discussion on his book at Observer Research Foundation, Delhi on March 30, 2016 . Other speakers were Dr. Shashi Tharoor, noted author and Ms. Suhasini Haider, Foreign Affairs Editor of The Hindu newspaper.

Mr. Ray said that popular perception prevailed that when it comes to diplomacy, Indians are naïve and in need of Western tutelage. He cited examples from Indira Gandhi’s nuclear tests, which led to several analysts mocking her. Awe-inspired by the nuclear diplomacy of the West, they were condescending about India’s attempts to do the same.

He said that after the idealism of the Nehruvian era, the realpolitik of the Indira and Rajiv years concerning nuclear diplomacy was considered to be a mimicking of the Western ways by most policy pundits. However, they missed out on a key aspect: that India was practicing a unique brand of diplomacy. The concept of ‘no-first-use’, hitherto unknown, was a unique contour of India’s policy, which effected change on the ‘Mutually Assured Destruction’ (MAD) doctrine in an influential manner.

Mr. Ray then delved into India’s traditional thought by claiming that the Indian approach to the world based on non-violence was not out of weakness. The Hindu spiritual tradition was a distinct philosophical approach to the world, which stressed on the concept of contextualism — categorically different from the intellectual history of the Christian, Muslim and Jewish faiths. The Mahabharata is a prime example of the fact that philosophical Hindu texts did not spell out what is right and wrong. It was a classic case of not going by the book, but adjudging situations based on context and deciding what was right and wrong. Moreover, the Hindu faith placed emphasis on interconnectedness of all beings; consequently arguing that any act of violence was ultimately a form of self-harm.

Moving beyond the Hindu faith to the innate Indian character, Mr. Ray argued that Indian Muslims had proven they were not as susceptible to radical jihadist propaganda as Muslims living in other parts of the world — simply due to the reason that they believed in practicing the ideals set forth by the Holy Quran, thereby eschewing West Asian philosophy. He recounted the story of Akbar, when the Ottomans ejected his wives on Haj on the claim that they were “behaving inappropriately, singing and wearing unsuitable clothing”. Akbar reacted by expelling the Ottoman ambassador and making a treaty with the Portuguese, their enemy. This showed just how far Muslims had become assimilated into Indian society — insofar as to act against their Muslim brethren in collusion with foreigners.

He ended by saying that the British rule brought a close to the Indian practice of contextualism via race segregation and prohibition of allowing princely states to pursue independent diplomacy.

Ms. Suhasini Haider said the very idea of a Hindu way of diplomacy was very exclusive and not palatable to the diverse culture of India. She also claimed that Indian diplomacy was not built on an ancient culture — rather on modern precepts of foreign policy making.

Countering Mr. Ray’s claim of an idealistic Indian spiritual thought, she spoke about the concept of creative truth and the story of Ashwathamma as cited in the Mahabharata — where Yudishthira lied to Guru Drona in order to defeat him in battle. She also expressed her views on “neti, neti” (not just this, not just this) as reflective of Indian foreign policy where it was characterized more by the things it was not. She had severe criticisms to make of the Indian bureaucracy, one she claimed was painfully short of funds and manpower. Regarding the flexibility (or lack thereof) of Indian diplomacy, she said that Indian diplomacy had been accused of both along varying points in time.

She did agree, however, that some ancient systems were deeply embedded in the foreign policy of India, borrowed from traditional Hindu thought. The idea of non-alignment, charted by India, was a concept most sides involved in the Syrian conflict have been pondering over — whether it would have been a better alternative to simply not take sides. The radio address by Jawaharlal Nehru in 1946, where he espoused the ultimate aim of Indian foreign policy to be the emergence of evolution across the world in the manner of vasudeva kutumbaka.

Dr. Shashi Tharoor praised the book for its solid research and unique perspective into the roots of Indian diplomacy before saying that in his opinion, the idea of a ‘Hindu’ way of diplomacy was “cogent, yet contestible”. He argued that the usefulness of categories such as Indian and Western was highly suspicious. Nehru’s was not a Hindu mind; rather being deeply influenced by collective readings of Western works and his education at Harrow and Cambridge, he retained a great impatience with the Indian way of doing things. Some called him the “last Englishman left in India”. Also, the principle of tolerance as espoused by Ray to be an essentially Hindu thought based on the Mahabharata had been applied by Bangladesh following the bitter war of 1971 with Pakistan. In fact, the entire concept of non-violence was becoming alien to India. He cited the raid of Myanmar, stating that there had been nine such raids in the past, but none announced in the bellicose language as the one the current government had chosen to use.

Finally, considering the structure of Indian diplomacy, Dr. Tharoor cited the memoirs of Badruddin Tyabji, an eminent diplomat and thinker, who said that Indian diplomacy was really so much ad-hocism with no coherent strategy, just Nehru’s personal blueprint on foreign policy. Pulling up Ray’s point on Indian diplomacy’s capacity to find reason in the other side’s arguments, Dr. Tharoor cited David Malone in saying that more often than not, Indian diplomats win arguments, not friends.

Yet Dr. Tharoor agreed with Ray in his statement that non-violence did not correspond with passivity, and with Ms. Suhasini Haider in the fact that mere negation of something is not negation, but a vision of what it could be.

This report is prepared by Mikhil Rialch, Research Intern, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.