-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

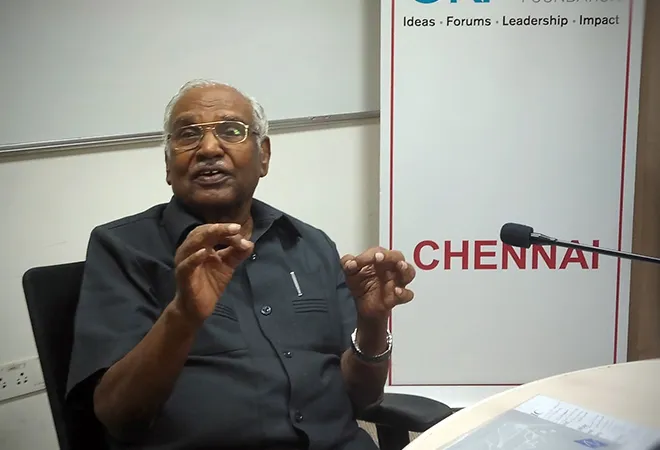

“There is an urgent need for the government and the private sector to create and nurture a scientific eco-system that is multi-faceted and multi-talented,” observed Dr M Anandakrishnan, educationist and science expert, who was also a former Chairman of IIT-Kanpur and also of the Madras School of Development Studies (MIDS).

Initiating a discussion on the challenges and opportunities involved in creating a scientific eco-system at ORF, Chennai on 1 September 2018, the nonagenarian expert said that though India was becoming an economic power-house in its own right, there has been a dearth of world class scientific inventions and investigations. This was because the nation has not succeeded in meeting the challenges faced in creating a scientific eco-system.

Just like in the natural world, a scientific eco-system can remain static or be dynamic, can flourish or deteriorate, depending on several factors that impede or encourage it, Dr M Anandakrishnan said. It was incumbent upon both the government and the private sector to ensure the creation and maintenance of an eco-system in which the scientific community in India can make enormous strides and in turn contribute to the scientific world at large, he claimed.

“Three main factors can affect a scientific eco-system – namely, leadership, resource-input and scientific-temperament,” Dr Anandakrishnan said. Pointing to the importance of good leadership, he explored the positive impact made by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi during the Pokhran-I nuclear experiment in 1974, and later by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee during Pokhran-II in 1998. Their leaderships faced off all fears and anxieties nearer home and international pressure, on the two occasions, he recalled, spelling out the details and specifics.

On both occasions, the interpersonal relationships between the nation’s political leadership and the scientific community tasked with those sensitive experiments stood out, Dr M Anandakrishnan recalled further. It had begun with Prime Ministers, Jawaharlal Nehru and Homi J Bhaba, Indira Gandhi and Vikram Sarabhai, and Vajpayee and the later-day President A P J Abdul Kalam and the rest. In this context, he also related to the contributions of the late C Subramaniam and Dr M S Swaminathan towards ‘Green Revolution’, Dr Sarabhai, Dr Satish Dhavan and Prof U R Rao on the space front, and of Prof M G K Menon in terms of ‘particle physics’, the latter at the abandoned mines of the Kolar Gold Fields (KGF).

They were all pioneers, who kept alive the scientific eco-system, demonstrating the need for strong leadership and visionary thinkers. These research successes under their strong leadership helped the nation to become a hub of Information Technology (IT), when the opportunity arrived with attendant challenges, he said.

In this context, Dr Anandakrishnan also recalled how in the case of Pokhran-I, the strained equation between Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and then US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger too contributed to the American view on the subject, though that was not the only factor. The Indira Gandhi leadership standing up to the global dominance of the US in general and Secretary Kissinger in particular also added to the nation’s image. On balance, he credited the leaderships of Mrs Gandhi and of Vajpayee later on, for sustaining the momentum in the nation’s scientific progress, he added.

Dr Anandakrishnan felt that the lack of visionary leadership could be felt since in core sectors like agriculture, particularly at the State-level. In 1967, Tamil Nadu, for instance, had 42,000 lakes, tanks and large water bodies, for irrigation, but today their numbers have been reduced to 7,000. In the intervening decades, many of them have been encroached substantially or have turned into filthy cesspools owing to neglect. Dr Anandakrishnan lamented that de-silting was not taking place in the canals and their waters remained murky. Compared to the progress made in space and nuclear technology, agricultural development and progress had failed the nation, he said. This, he recalled, was so after the great strides that the nation had made in the era of ‘Green Revolution’.

Scientific temperament was the key to maintaining a scientific eco-system. Dr Anandakrishnan felt that there was abundance of scientific temperament in ancient India and the range of it was evident looking at the works of Aryabhatta and at the brilliance of architecture and engineering seen in temples such as Rameswaram. While there was scientific temperament in contemporary the country, as evidenced by the progress made by world-class multi-disciplinary research organisations such as ISRO, BARC, Chennai Mathematical Institute and the Indian Statistical Institute, he criticised the universities in the country for lagging behind when it came to research. This was so because they were all more focused on teaching. This trend had to change, he said.

Resource input and funding was equally important in creating a scientific eco-system, and this is where the nation faced the most challenges, regretted Dr. Anandakrishnan. Philanthropic money is often essential for getting scientific projects off the ground, while Government funding comes in at a later stage.

“Institutes like MIT in America are able to attract billions from the private sector. Why don’t the billionaires in India give to the scientific community?” asked Dr. Anandakrishnan. In this context, he said that private funding for scientific research in percentile terms against the GDP, was higher in China and Japan and other East Asian countries than is being made available in India.

Scientific eco-systems, much like natural eco-systems, in times of stress, break down and new ones evolve in its place. The crucial elements to keep them alive were a passion for learning described as “scientific temperament”, leadership at the political level and the level of founders and leaders of research institutes, and finally financial resources/funding. Without big-time monetary support, a scientific eco-system cannot sustain itself, concluded Prof Anandakrishnan.

This report is prepared by Dr Vinitha Revi, Research Associate, ORF, Chennai

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.