ISIS influence in a post-geography terror threat

The ISIS’ conception in the post-Iraq war of 2003, its growth in the succeeding many years and, finally, its supposed ‘demise’ a couple of years ago—resulting in the geographical end of the so-called Islamic State—is a narrative that has been repeated both by governments and independent analysts alike over the past few months. This author has himself written a paper, ‘The Fall of ISIS and its Implications for South Asia’, that studied the future trajectory of ISIS and the form in which it will now strive.[i] As the year 2018 opened, the fight against ISIS—both military and in the realm of narratives—had taken the backseat in mainstream and regional media. However, questions remain on not only the finality of the so-called ‘defeat’ of the Islamic State but the fate of the ideology itself. After all, such ideology was successfully disseminated not only in Iraq and Syria but also to a global audience via the group’s impressively organised internet outreach.[ii]

Despite the prevailing narrative, there is no consensus amongst those who study ISIS and the Syrian civil war on what the future holds, and whether this celebrated defeat means only a geographical suppression or a larger, ideological breakthrough to break the backbone of the movement. “Beneath this mask, there is more than flesh. Beneath this mask, there is an idea, and ideas are bulletproof,” so says the lead in the American fiction film, ‘V for Vendetta’, based loosely on British anti-establishment revolutionary Guy Fawkes who tried to blow up the British parliament in 1605. The ethos behind this quote, generously provided by American pop-culture, resonates with the basic question over the future of ISIS. Theology plays a critical role within ISIS despite being underappreciated in public discourse as a pivotal reasoning behind the group’s success.

The life of the Islamic State in its post-geography phase will likely be the subject of many case studies, as the group evolves and trains its sights on regions beyond Iraq and Syria. Indeed, it has already garnered some degree of success in this sphere—with ‘lone-wolf’ attacks attributed to IS in Europe, US and other regions—and the coming of ‘ISIS 2.0’ has become an accepted fact amongst scholars and analysts who follow the organisation.[iii] While it is imperative to remember that ISIS works strongly on a psychological level, and is expected to intensify its approach of radicalising potential recruits online, the post-geography era of the group offers a bigger challenge than that which can be defeated by military operations against a semi-defined proto-state. The relapse of the Islamic State into its original form, that of an insurgency, is inevitable. Current responses by regional powers, non-state militias and external powers are proving to be nothing more than a Band-Aid over a scrape; what is required, however, is major surgery and rehabilitation.

While Iraq has arguably witnessed a more successful approach to plugging political vacuums in the wake of defeating ISIS in prominent cities such as Mosul and Tikrit, the prevailing situation in Syria was always going to have a polar-opposite outcome. However, the effects of ISIS on global debate, the war on terrorism and how states approach tactical outcomes of both military and political insurgencies and terror groups alike is expected to drastically change based on the strategies employed—and now institutionalised—by ISIS.

India is often highlighted as an ‘anomaly’ as far as the influence of ISIS is concerned. As a country with the world’s third largest Muslim population (after Indonesia and Pakistan), the number of ISIS cases that have been, or are currently being probed by investigative agencies remains just above 100, with liberal estimates hovering around the 200 to 300 range. Even with the higher estimates, the numbers are lower than most European countries that have seen foreign fighters move towards Iraq and Syria in sizeable numbers. The number of Indians who managed to travel to either West Asia or Afghanistan to answer ISIS’ call between 2014 and 2016 is around 10 to 15.[iv]

These trends often raise the question of whether ISIS failed in India. How deep were its organised attempts to develop a presence in India, and what threat perceptions persist from a geographically depleted organisation? This paper dissects the Indian cases and picks out patterns about what have led individuals to join the so-called Islamic State’s ‘caliphate’. The research relies predominantly on data provided by government and state investigation agencies, due to a lack of other, independently verifiable sources.

The Initial Pro-ISIS Cases in India

During the period of 2012-2013, New Delhi under the government of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was proactive in the international multilateral efforts to develop a global consensus in ending the hostilities in an increasingly ravaging Syrian civil war. In 2014, then Indian Foreign Minister Salman Khurshid addressed the Geneva-II meeting, reiterating India’s stance on a peacefully negotiated end to the war and New Delhi’s commitment to humanitarian efforts in Syria. “India believes that societies cannot be re-ordered from outside and that people in all countries have the right to choose their own destiny and decide their own future,” the minister said.[v] “In line with this, India supports an all-inclusive Syrian led process to chart out the future of Syria, its political structures and leadership. There can be no military solution to the crisis. India’s stand on various resolutions in the Security Council and General Assembly has been in support of efforts to bring about an end to violence by all parties. India has important stakes in the Syrian conflict. It shares deep historical and civilizational bonds with the wider West Asia and the Gulf region. We have substantial interests in the fields of trade and investment, diaspora, remittances, energy and security. Any spillover from the Syrian conflict has the potential of impacting negatively on our larger interests.” Since then, the Geneva talks have served as a monument to the utter failure of the United Nations and the international community to bring an end to the civil strife.[vi]

During the same year of India’s participation in Geneva, the first few cases of Indians getting involved in pro-ISIS activities started to come to light. From 2011 till 2013—the timeframe during which the erstwhile Al Qaeda hierarchy in Iraq re-branded as ‘ISIS’—Indian approach towards the crisis was largely based around the paradigm that it was contained within the Middle East region. This gave Indian security agencies a false sense of security on the precise nature of the group and how it planned to expedite its own strategies, which from the beginning included establishing a geographic foothold in Iraq and Syria followed by global outreach methods. To be fair, however, New Delhi’s blind-spot to the development of the so-called Islamic State was not unique; the group’s rapid advances both geographically and using the internet as its second battlefront took the entire world by surprise.

The first two prominent cases of Indians being involved in pro-ISIS activities occurred in Singapore and the town of Kalyan in Maharashtra. Two childhood friends, Haja Fakkurudeen Usman Ali, a manager at a grocery store in Singapore and Gul Muhamed Maracachi Maraicar, a software engineer in a multinational firm became part of a plot to join ISIS and travel to Syria. Both Ali and Maraicar, born and brought up in Cuddalor, Tamil Nadu, witnessed the Syrian crisis unfold from 7,600 km away and were moved by the plight of the Muslims suffering in the conflict. This being the earliest in the timeline of the rise of ISIS as a global phenomenon, Maraicar and Haja’s radicalisation seems to have been rooted in witnessing images and consuming news via mainstream media before attempting on their own to access ISIS propaganda online. The plan was built by the two between 2011 and 2014, with trips to India in the middle to consult family members and plan their move to Syria. In this duo, it was Gul with a steady job and the financial resources, who prodded Haja to carry out the travel. In 2013, Haja visited Cuddalor to seek blessings from his parents and prepare his family to travel with him. Despite his parents’ attempts to dissuade him, Haja left for Syria along with his family. (There is little clarity on the route they had taken, but it was likely via Turkey which was the preferred transit for most foreign fighters.)[vii] Haja would later be featured in ISIS propaganda videos in 2016.[viii]

Meanwhile, Singapore authorities arrested Maraicar and deported him back to India. During investigations, Maraicar had revealed that both him and Haja had planned to expand recruitment for ISIS and had looked into tapping into educational institutions in Chennai. The fallout of Maraicar and Haja’s plans were visible even in 2017, four years after the latter left Indian borders. In September 2017, at least five individuals were arrested in Tamil Nadu, with one of them, Ansar Meeran, being found as the financier behind Haja travelling to Syria with his family.[ix] Meeran and associates worked towards furthering the agenda, arguably failing to do so in the four years they remained at large.

The other, popular pro-ISIS case to emanate from India was of the four young men who left their homes in Kalyan, Maharashtra in 2014 and successfully made it to Syria. Amongst the four was Areeb Majid, son of an unani doctor, whose radicalisation story predated the formulation of ISIS in all its forms. The others who fled with Majid were Fahad Tanveer Shaikh, Aman Naeem Tandel and Shaheem Tanki. All four of the Kalyan men faced different fates as members of the so-called Islamic State. Majid was the only one of the four who eventually surrendered and was brought back to India from Turkey, tried and jailed; Tandel, Shaikh and Tanki were reported killed over the period 2014 – 2017.

ISIS in South Asia: Ideology vs Ground Reality

On 27 February 2018, the US State Department announced a host of ISIS ‘affiliates’ to be designated as terror organisations.[x] From South Asia, Bangladesh for the first time appeared in an official communique of this kind. The group is called ‘ISIS-Bangladesh’, which by accounts will represent an umbrella to include all factions of the Neo-Jamaat-Ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh (NJMB) and smaller groups if further terror acts are committed in allegiance to ISIS.[xi]

The neo-JMB in Bangladesh would not have had much difficulty as far as recruitment goes, with there being enough interest in Bangladesh to market the Islamic State’s ideology. In 2016, one Mohammed Mosiuddin (alias Abu Musa), a 26-year-old grocer from West Bengal’s Burdwan region was arrested for allegedly planning lone-wolf attacks in the name of ISIS, including those against Western targets.

Mosiuddin took to online platforms in 2014 to get in touch with more like-minded people, and scope out the activities of pro-ISIS supporters in the region. During this search, he came in contact with many such individuals, including Shafi Armar (alias Yusuf al-Hindi, founder and self-appointed Emir of Junud-Al Khalifa-e-Hind), also known to be a resident of West Bengal and a known former Indian Mujahideen operative seen as the Islamic State’s predominant ‘recruiter’ for India. However, during this period, Mosiuddin also came in contact with Abu Sulaiman, a former member of the Jamaat-Ul-Mujahideen (JMB). Initial communications took place via Facebook and then switched to various other platforms such as Nimbuzz, Surespot and Trillian. The communications between Mosiuddin, Sulaiman and others took form fast, albeit in an unorganised and ad-hoc manner. In 2015, the JMB joined these conversations while Mosiuddin attempted to get financing and help in obtaining a passport from Armar in order to plan his travel to Syria. Meanwhile, Sulaiman paid Mosiuddin a visit from Bangladesh to decide the course of action they wanted to initiate for setting up ISIS’ presence in the region. It is unclear how Sulaiman arrived in India (though taking conventional modes of transport such as air or road would have been most likely).

People like Armar are guided by ISIS to become effective recruiters, giving them access and information on how to convince probable candidates into joining their brand. While the differences between the likes of Al Qaeda and ISIS are mostly glaring, some strategies are common between the two, including the weaponisation of the internet via selective militarisation of the Quran. Jesse Morton, who was a former online recruiter for Al Qaeda and went by the name Yonus Abdullah Mohamed, has explained the three-point agenda that is used (at least by him and the radicals he was in contact with) to pull potential recruits towards their ideology. The entry point, as explained by Morton and one that occurs repeatedly in examples of radicalisation of individuals across the board—is personal grievance, a dent in a person’s psyche that can be nurtured in a negative manner and used to contribute to a broader cause.[xii]

This strategy is divided into three silos. The first is Tawheed al-Haakimiyyah, or the promotion of undisputed idea that Allah and his judgement and legislation (Sharia law) is supreme. Second, Kufr bin Takhud or the complete rejection of ‘false gods’, which includes idols, elected democracy, parents if they stop you from joining the greater cause, and so on. Lastly, Al-wallah-al-Burrah, complete loyalty to Muslims and only Muslims. These tenets to radicalisation, mixed with global events such as the Syrian civil war—images of which are livestreamed on television and even more easily available online—offer a potent concoction for recruiters. The flip side of the coin is that the targeted individual also needs to have more than just the sense of social, cultural or political disillusionment. The sense of ‘purpose’ and, perhaps surprisingly, boredom and the lack of achievements and purposelessness are also highlighted as personal traits that jihadist recruiters pry on.

Between Mosiuddin and Sulaiman, the former also tried to recruit two others—Saddam Hossein, a 25-year-old unemployed youth and Shaikh Abbasuddin, a 22-year-old daily wage plumber. Mosiuddin demanded complete loyalty to him of both the men, and set out to build an agenda. This included, in consultations with Sulaiman, recce trips to New Delhi and Srinagar in 2015 via train, where failed attempts were made to rile up protests with ISIS flags, video clips on YouTube and trying to make space for the Islamic State’s ideology in the valley. Mosiuddin’s JMB-sponsored trips pushed him to pursue his initial ideas further, to fight in Syrian soil. It never came to fruition due to financial problems and Armar’s inability to provide them with monetary support, even via JMB, who described Sulaiman as an ISIS cadre.[xiii]

On the other geographic side is Afghanistan: while posing much less of a threat to India directly, it has become a battleground as far as ISIS goes and is home to the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP). Both the JMB and ISKP’s relations with ISIS are distinctive enough for the mandate for them to have a separate dedicated study. However, Afghanistan already has the second largest pro-ISIS presence outside of Syria and Iraq. This presence has more to do with Afghanistan’s local jihadist ecosystem and domestic and regional political dynamics than a devout allegiance towards the caliphate. Here, many jihadists know of no other way to make a living other than waging a war, and ISKP has taken advantage of this talent pool, as have others. For example, Iran hired hundreds of fighters from the Liwa Fatemiyoun, an Afghan Shiite militia largely funded by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), and deployed them on the frontlines in Syria. Meanwhile, ISKP largely comprises of former Pashtun fighters of the Taliban displaced by Pakistan’s military operations along its borders with Afghanistan.

Mosiuddin’s example highlights not just an Indian case, but one of the many South Asian and South East Asian examples of pro-ISIS people looking to undertake hizrat, or the holy trip to Syria to fight in ISIS in the name of God. While the men from Kalyan in Maharashtra were economically more stable, Mosiuddin, a small grocery store owner, had to repeatedly ask Armar for monetary help, not just for his intended travels but to procure small locally manufactured weapons as well, including knives, swords and machetes (tools often seen being used for grotesque violence in ISIS propaganda videos). The important aspect in this case, however, was the seemingly easy way that Mosiuddin and Sulaiman were able to collaborate across the border. These recent worries of Islamist radicalisation in Bangladesh on the back of the Rohingya crisis in neighbouring Myanmar also provoked a barrage of reports—mostly unsubstantiated and uncorroborated—detailing the supposedly rising influence of ISIS amongst the refugees, in refugee camps and in the general Rohingya population. The more direct threat of radicalisation remains with the tapping of local organisations such as the N-JMB by larger global jihadist factions such as Al Qaeda, empowering them economically, ideologically and militarily to use the Islamic State brand and orchestrate jihad. (A comparative case is militant group Abu Sayyaf’s allegiance to ISIS and the impending battle with the state in Marawi, Philippines). The trend of multiple parties claiming attacks to both hijack and confuse narratives is commonly observable in examples from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and even in India’s Jammu & Kashmir.

Mosiuddin’s case highlights an important factor—that a person’s ability to understand and tackle day-to-day life issues also plays a role in their planning abilities to either commit an act of jihad or attempt to travel abroad to join a terror group. Dealing with the system for simple tasks such as obtaining a passport was a failed exercise for Mosiuddin. It remains unclear to what extent Armar was willing to help Mosiuddin. However, it can be safely presumed that the distance and the limited worldliness of Mosiuddin made sure Armar either failed in equipping him or eventually gave up.[xiv]

Despite the number of pro-ISIS cases being relatively negligible, the Indian political and social environment remains conducive for Islamist activities with multiple social and political pressure points. However, there remains a distinction between the Indian cases who bought into the caliphate’s marketable jihad and the historic connotations of what has fueled Indian jihad—which largely has been the issue of Kashmir.

Mapping Pro-ISIS cases in India

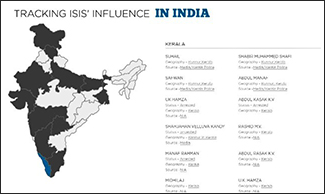

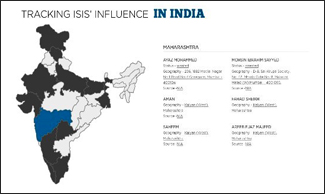

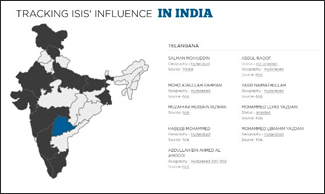

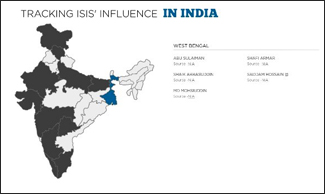

(Snapshots of ORF’s ISIS Influence Tracker project showing data from the states of Kerala, Maharashtra, Telangana and West Bengal as examples)

According to research conducted as part of this paper and the ones preceding this, the number of pro-ISIS cases attributed to both the National Investigation Agency (NIA) and the media stand at 112. The process of collecting the data was challenging despite some of it being made publicly available by the NIA. It was difficult to formulate a clear hypothesis on both the outcome of a concentrated effort by either ISIS or pro-ISIS individuals to set up an exclusive India entity, which in turn made it harder to adhere to systematic (or traditional) use of research methodologies.

The mapping of the 112 cases in India threw both interesting data and expected trends. Kerala, the most literate state in India, led the number of pro-ISIS cases with 37 out of 112. The numbers are expected to be higher, however, as per corroboration done for this research, the count that includes cases that could not be fact-checked does not exceed 150. These cases are of those in India, or that began in India. The number of Indians who have or may have joined ISIS or travelled to Syria or Iraq from within West Asia or other foreign points remains a grey area with little to no data available. More than seven million Indians reside in the larger West Asia region, and this lack of data is problematic both for mapping trends and in the overall attempt to study ISIS’ influence and alleged footprints in India and its neighbourhood.

It is hardly surprising that Kerala leads the number of cases of radicalisation towards the Islamic State. Despite its literacy rates, as a state, Kerala depends on remittances from the Gulf region for much of its economic well-being, which in turn translates into the Gulf’s political influence as well. Other states such as Maharashtra, Telangana and West Bengal have also witnessed comparatively higher incidence of radicalisation. The seriousness of each case, however, varies—from being a concentrated effort to simply wishful thinking.

There are few commonalities between the cases but they do help construct some patterns that may be of significance in studying counter-terrorism from an Indian perspective. As it is known, radicalisation online promoted by the Islamic State’s well-orchestrated media propaganda arms became the easiest platform to access both for jihadists and potential jihadists. Almost 95 percent of all cases in India started from the online sphere, and not necessarily ended in contact with either ISIS or pro-ISIS recruiters, but with access to the hordes of general propaganda that includes text documents, videos of executions, speeches by prominent clerics, well-produced glossy magazines such as Dabiq (later renamed Rumiya after the town of Dabiq fell away from the caliphate’s control), and other such paraphernalia.[xv]

The most common apparatus for contact and outreach between most cases has been Facebook, which is an anomaly given global trends. The uses of Facebook range from direct messaging, to creating new profiles specifically for pro-ISIS activities using dedicated mobile phones and numbers, to having a relatively free access to both like-minded folks and materials shared by them as the platform itself struggles to curb misuse of its services. One commonality that can be sketched out from the available data is the fact that potential pro-ISIS individuals seem unwilling to work alone. Like any ‘fan club’ that works online for celebrities, the method to rally support for pro-ISIS ideology does not involve specialised tactics as far as most Indian cases go. Other chat programs such as Telegram has become popular as official ISIS channels and pro-ISIS activities started to use the Russia-based software more often due to its higher encryption levels that make it harder for governments to break into it and orchestrate surveillance against its users. Initially, non-encryption of the popular messaging app WhatsApp (owned by Facebook as of 2014) was one of the reasons pro-ISIS figures did not use the service. Absent empirical studies, an argument can be made that this allowed India’s nearly 200 million WhatsApp users a deterrent via the lack of a privacy option that was fast becoming common amongst other providers.[xvi]

The need to work in a group rather than alone in trying to plan attacks locally or attempting to travel to Syria has both commonalities and anomalies to how potential ISIS recruits behave. Europe has seen what has come to be known as ‘lone-wolf’ attacks, where a radicalised individual commits an act of terror in the name of the Islamic State, using daily items such as knives for stabbings or a vehicle to mow down pedestrians on busy city streets.

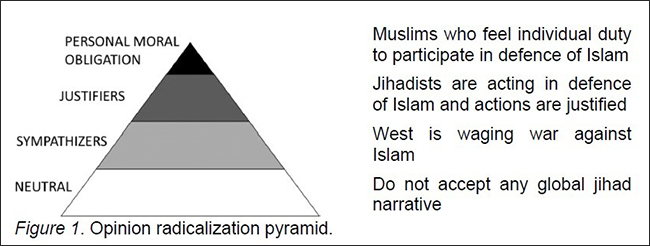

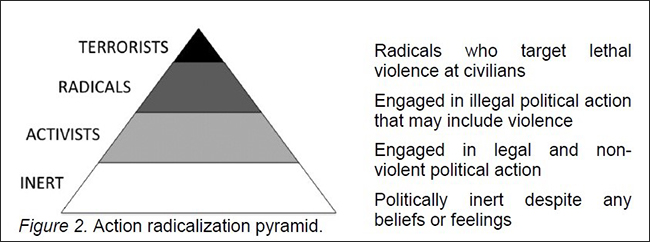

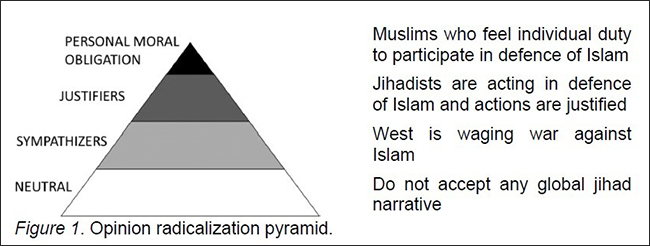

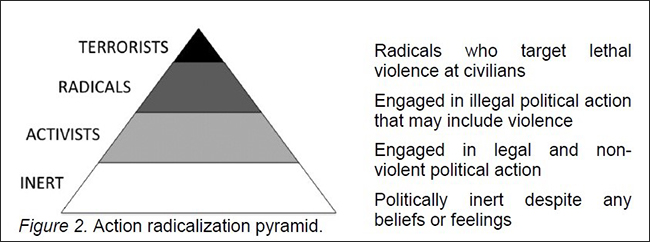

The concept of lone-wolf attacks was discussed by people such as Mosiuddin. However, it did not materialise in any of the cases studied for this paper. Before delving further into this aspect of Islamic State’s effect on people being radicalised towards jihad, it is imperative to clarify what a lone-wolf attack is and how it is identified. Clark McCauley and Sofia Moskalenko in their research have theorised two schools of thought, illustrated via the top-down pyramid approach—one to decipher Radicalization of Opinion (Figure 1) and the other, Radicalization of Action (Figure 2).[xvii]

Researcher Lewis W Dickson recognises the fact that the process of understanding terrorism conducted by solitary persons—and how they moved from harbouring opinions on a matter to conducting an act of violence—is a transition that may not have any systemic variables.[xviii] Often, definitions of lone-wolf attacks, such as one formulated by Ramon Spaaji, highlight the fact that the attackers do not belong to organised terror networks and the person operates only on the behalf of themselves.[xix]

Despite the fact that most researchers have been unable to come to any concrete framework on how to define a ‘lone-wolf’ attacker, the lack of such incidents in the name of the Islamic State in India can indeed be seen as an anomaly. While not many detailed sociological or cultural research exists to quantify this from an Indian point of view, the fact is that most cases in India mostly involve groups of people.

At the beginning of this research it seemed that the ‘only-groups’ argument could either be common to Indian cases due to socio-cultural factors or other unknown reasons. Yet, similar trends were observed in a Canadian study released by the country’s Security Intelligence Service (CSIS).[xx] The output analysed Canadian cases over a three-year period to outline select findings, specifically looking into what pushed the people who travelled to Syria and Iraq to fight with ISIS from “talkers” to “walkers”, and what the factors were that bridged the process between thought and action.

The CSIS study found that the tendency for younger people to work in groups and not alone is one that was commonly observed. This hews to observations made in most Indian cases as well. The following section from the CSIS puts things in perspective from a common experience point of view between India and Canada. “The Service’s analysis found that young adults (under the age of 21) and minors mobilize more quickly than adults. The mobilization process for youth, especially young travelers, is a relatively minimalistic endeavor. In extreme cases, it requires nothing but a passport, plane ticket and cover story for the travel. Young adults and minors have fewer obstacles to overcome in their process of mobilization and they also tend to mobilize to violence in groups, which can also help them overcome any existing obstacles by pooling resources and expertise.”

Further, the analysis highlights that group mobilisation is faster, and offers better cover to hide violence indicators. The research also showed that socio-cultural factors such as marriage, relationships, and others play an important role in mobilisation patterns, specifically for women, who rarely move about on their own, given cultural norms.[xxi]

The pattern of moving in groups from an Indian perspective also has similar points of experience as those seen by Canada. The age demography studied by CSIS and the median age in the Indian cases are comparable, other than the fact that there were hardly any cases in India of minors either travelling or showing signs of pro-ISIS activities. Both the Indian and Canadian experiences are distinct from those of European nations. For example, the Paris attack in November 2015 was a concerted effort between a group of young men residing in Brussels, Belgium, led by 26-year-old Salah Abdeslam, who is a Belgium-born French national of Moroccan descent.[xxii] While the attack was effective, it was also one of the less common types of violence committed in the name of ISIS in that country. The terror strike claimed 130 lives, and symptomatically, was much different than the debated fear of lone-wolf attacks in European capitals, specifically as the number of Syrian refugees looking to enter the continent grew significantly during that period. All the attackers knew each other and belonged to the same locality in the Belgian capital’s impoverished and mostly Muslim-populated Molenbeek area. Some of them were childhood friends.

A comparative to the Canadian and European examples is the Indian case of a short-lived, 12-hour-long siege in March 2017 between the Uttar Pradesh Anti-Terror Squad (ATS) and terror suspect Saifullah, who was alleged to have links with ISIS and was killed in the operation in UP’s capital Lucknow’s Thakurganj area. This particular case had other political and sociological commonalities as well when compared to other pro-ISIS cases in Western countries.

The Case Studies: Comparatives and Trends

On 7 March 2017, a crude, home-made low-intensity pipe bomb was used to orchestrate a terror strike on a passenger train operating between Bhopal and Ujjain in Madhya Pradesh. More than ten people were injured. Some of the accused were arrested over the next few hours, and investigation agencies uncovered an alleged connection to the Islamic State. The men behind the bombing chargesheeted by law enforcement were Atif Muzaffar, Mohd Danish (alias Jaafar), Syed Mir Hussain (alias Hamja Abu Bakkas) and Ghous Mohammad Khan. Subsequent investigations pointed to Muzaffar as the ring-leader, with the other three and another man, named Saifullah, as collaborators.[xxiii]

Following the attacks, media reports were quick to point out that this was considered to be the first ever “full-scale Islamic State operation in India.”[xxiv] The men involved were in contact with each other via social media platforms, and were reportedly being monitored by a web of central and state intelligence and police agencies. In cases prior to this one, foreign intelligence agencies monitoring pro-ISIS radicalism worldwide in more than one instance had alerted Indian authorities about such chatter. It not only highlighted cyber-security blind spots from an Indian intelligence point of view but also proved just how easy it had become for potential jihadists to use popular social media platforms for initial connections with like-minded people, before attempting to take the conversations to mobile messenger services or offline.

In Lucknow, recovered in the house where Saifullah was killed were weapons, a flag of ISIS, cartridges and videos of pro-ISIS materials. All the men arrested in this case had unconfirmed common threads with not just each other, but a ring that Shafi Armar may have been trying to build across the sprinkled sections of the rapidly growing Indian penetration of the internet and mobile services. All the accused in the Lucknow case also came from modest backgrounds, and did not have the financial resources to travel to Syria or Iraq despite showing inclination to do so via Dhaka in Bangladesh.[xxv]

It is known via investigations that Saifullah and the others as well during questioning raised the issue of the rise of the Hindu far-right and groups such as the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) being threats to Muslims in India. This point is not exclusive to the Lucknow case, but is brought up in nearly 45 percent of all cases studied as part of this research.[xxvi] The news cycles in the Indian media of the mob-lynching of Muslims in the recent past and attacks on Muslims due to events related to consumption or sale of beef are also common trends flagged throughout this exercise. While these issues are contentious, there is no empirical evidence available or no such conclusions achievable whether these were at the forefront of radicalisation, or just one of the many factors that lead a person to taking a resolve to join the Islamic State.

One of the most interesting aspects visible throughout has been the fact that the fascination of joining the geographical entity of the “caliphate” in Iraq and Syria by far trumped any will of these people to represent ISIS domestically instead. While the above particular case can be registered as an anomaly, the foremost attempt has been to try and travel to the Middle East. Out of the majority of the cases studied here, very few had ever stepped outside India, and most of them did not even have valid passports. The biggest obstacle for these cases looking to fly out of India was, for better or worse, the Indian bureaucracy itself. Many of these cases had rejected passport applications due to lack of address proof or an actual permanent address, inconsistent documentation, and lack of understanding of the application processes. Those who reached the part of the process that required police verification as well had little success beyond that.

The fact that most cases came from people who had never left India before may have added to the increased arrest rates. Online visibility and collaboration remained the primary method for accessing ISIS’ robust, effective and well-produced media propaganda; even in ISIS’ downturn stages, such propaganda was available easily enough for both recruiters and consumers to distribute and access. For example, websites such as Jihadology.net, an academic repository of jihadist propaganda maintained by researcher Aaron Y. Zelin of the Washington Institute in the US, is banned in India by the Department of Telecommunications after interrogations revealed some of the cases had accessed the database for propaganda materials including speeches and videos.[xxvii]

The cyber sphere has been cultivated and used by ISIS not only to disseminate its propaganda, but to shape thought and play up the narrative of Muslims around the world needing their own land under the ISIS’ interpretation of Sharia. The design of ISIS messaging for its intended consumers, according to researcher Haroro J Ingram, works on two main factors. The first is the pragmatic side of the propaganda, which perhaps is the most important as it highlights the aspects of “security, stability and livelihood”. The second factor is largely based on the self, tapping into a person’s identity, highlighting the narrative—“we are champions and protectors of Sunni Muslims”— and offering protection of integrity.[xxviii]

However, a pattern, once again, cannot be determined on what exactly within the available ISIS propaganda materials convinced the Indian cases to take the step of joining the Islamic State. The anomalies, more than anything else, highlight the innate complexities in attempting to conduct scholarly studies of terrorism and radicalisation, especially narrowing the syllabus down to a few particular trends beyond theology and geo-politics. One hypothesis that can be constructed, yet not corroborated with empirical evidence within the bounds of this particular study, is that in most cases pre-existing disillusionment (or standing right on the cusp of the ‘line of radicalisation’) is key in nudging the person over the edge. While many reports highlight that friends and family tend to not notice any signs of abnormal behaviour in the person, discontent in the person’s mind had indeed been brewing either on domestic, international or personal issues. In the cases examined for this study, the reasons for crossing the line and looking to join ISIS range from fear of the rise of the Hindu right, the plight of Muslims in the post-9/11 world, and the suffering of Muslims in the Middle East in the hands of foreign powers. The latter is in itself vague, since most people who have died in the hands of the Islamic State have been Muslims themselves. The advent of the ISIS media machinery was a valid and safe stepping stone towards further radicalisation. In certain cases, the Indians involved were already members of groups such as Indian Mujahedeen, Ansar ut-Tawhid fi Bilad al-Hind (AuT), Popular Front of India (PFI), and other more marginal prior to the existence of ISIS. They used the opportunity to brand themselves with this latest global jihadist offering, and became part of a small but existing pool that ISIS unknowingly tapped into.

Kashmir and the Influence of ISIS

Despite the various theories and arguments being offered in an attempt to understand pro-ISIS radicalisation, the issue of Jammu & Kashmir remains a perplexing question. According to discussions with Indian cases by investigative agencies, there seems to be no single narrative within ISIS on the issue of Kashmir. Even as ISIS flags have sporadically been waved at protests in the Kashmir valley, in some instances the imagery itself has been wrong[xxix] and the effects of it on the ground have been minimal. The failure of attempts to construct a narrative around ISIS influence in the valley, despite various news reports suggesting the same, is grounded in the fact that jihad in the region is completely different ideologically and militarily than what the Islamic State looks to achieve.

The illustration of different narratives within the jihadist paradigm of Kashmir seen here highlights three main points on why the Islamic State will have difficulty to set up an official wilayat in India. First, the reasons for jihad are polar-opposite to the ones propagated by ISIS. Second, both the Indian state and Pakistani state are too heavily ingrained in the Kashmir issue, specifically institutionally, to allow space for any other organised narrative to take root. Third, the narrative of azaad Kashmir which also holds significant space is directly at odds with ISIS strategy and theology itself.

The predominant jihadist narrative in Kashmir is two-fold. The first are the pro-separatists who fight for ‘azaadi’, or freedom from the rule of both India and Pakistan. The second group consists of organisations supported by Pakistan, who hold in their nationalist discourse that Kashmir is part of Pakistan beyond just the Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (PoK). These two discourses leave little space for any other agendas by international groups such as ISIS, Al Qaeda, and others. However, this does not mean attempts have not been made, or are not being made, to install the principles of the caliphate in the valley.

“In my view, Kashmir was deliberately not chosen by Islamic State to launch their ‘Quest for Caliphate’ in al-Hind. Had it been chosen, there would have been two-front battles. First, with Indian Kuffar Army and second, with Pakistani nationalists, so-called jihadi groups Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT), Hizbul Mujahideen, Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) etc. Wallahi, these factions would never accept merger with Islamic State as their foundation is based on ‘nationalism’ or ‘patriotism’[xxx],” pontificated Mohammed Sirajuddin, a resident of Jaipur, Rajasthan, in a text message to a fellow radical. Sirajuddin was booked for promoting ISIS, inciting others to become part of the Islamic State and spreading pro-ISIS propaganda online.[xxxi]

Sirajuddin’s radicalisation was rapid, and he confided in his wife that he did not want to stay in India and that Kashmir was to become an Islamic State. He collected ISIS propaganda such as issues of Dabiq, had largely uncontested online reach in order to lure potential recruits and had built an online discussion group that included people from countries such as Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Indonesia, and even as far as Argentina. He often wrote “ISIS Welcome in Kashmir” on Indian currency notes and circulated pictures across social media. Like many in India, Sirajuddin was also obsessed with TIME magazine’s annual listing of ‘Person of the Year’, and advocated in his social media outreach that people hack TIME magazine’s website to declare al-Baghdadi winner of the said title. His affinity for ISIS had nothing to do with Kashmir, and was purely based on his outlook of Islam and where the religion stood in the global narrative. He also looked into travelling to Ramadi, Iraq, an oddly specific aim for a place from where ISIS was driven away in January 2016.

More than any success of an orchestrated effort to create pro-ISIS entities, what is noteworthy is the sporadic incidence of militant groups pledging allegiance to ISIS. For example, Nida-e-Haq, which was nothing but a pro-ISIS channel on Telegram which came into being, as per open-source intelligence (OSINT), after certain other channels dedicated to translating ISIS propaganda into Urdu were deleted from social media.

(An image released in 2017 by Nida-e-Haq via Telegram showing Kashmir draped in an Islamic State flag[xxxii])

As part of a video released by the group, a man identified as Abu-ul-Braa al-Kashmiri called on the people of Kashmir not to support either India or Pakistan, and also criticised the Pakistani government and its intelligence agency ISI for events such as the Lal Masjid (Red Mosque) siege of 2007 in Islamabad and the Pakistani military’s operations against militants in its restive Waziristan, FATA and other such regions. Ul-Braa made clear in his statement that his mandate is to dissociate Nida-e-Haq, which in effect was seen as ISIS in Jammu & Kashmir (ISJK) from all states, the United Nations and all other governmental factions and the international order. Nida-e-Haq is considered closer to ISKP’s hierarchies in Afghanistan and comments on what could be seen as a broader narrative not just for Kashmir but Pakistan as well. Its sister-entity, Al Qaraar, again on Telegram was known to purely focus on Kashmir and acted more as a hyper-local distributor of pro-ISIS propaganda instead of just another broad-stroke announcer of ISIS political and religious noise. (It is not known whether or not it is still functioning.) Some of the writings released by Al Qaraar were titled ‘Realities of Jihad in Kashmir and Role of Pakistani Agencies’ and ‘Apostasy of Sayed Ali Shah Gilani and others’—content that targets jihadist nomenclature in the valley.

With its new outreach, Unl-Braa also called on fighters from Ansar Ghazwat al-Hind, the group led by Zakir Musa, a Kashmiri militant, who announced the formation of the organisation via pro-Al Qaeda channels and propelled him to become one of the most recognisable names in the valley overnight. However, the elevation of Musa as one of the top five most wanted jihadists in Kashmir[xxxiii] also initiated a peculiar intra-jihadist battle between the likes of Al Qaeda and ISIS (via its Amaq News agency) attempting to lay claim while Pakistan sponsored groups such as Hizbul Mujahideen, which had expelled Musa from its ranks earlier attempted to reign him back to curb his growing prominence with the big-brands of global jihad.

The above example, along with that of Sirajuddin, present the two distinct narratives of how Kashmir is either viewed, or could be viewed by the jihadist norm culture in what is a restive and socially delicate state. The fact that Musa’s overnight fame was a direct result of being linked with global jihad’s two biggest brands in fact quantifies the phenomenon on what the brands themselves, or being associated with, are capable of without anyone actually either confirming, denying or acting in their name. To further pencil this argument in, the case of Eisa Fazili, a freelance jihadist thought to be a former Ghazwat al-Hind member in the valley who killed a policeman in Srinagar allegedly took it upon himself to sell his crime to Amaq News, which then pushed it as the first ISIS attack perpetrated in India. Fazili was killed in an encounter with Indian security forces along with two other militants, Syed Owais Shafi and Mohammed Taufiq. The latter, Taufiq, from Telangana, became the first non-Kashmiri militant to be killed in the valley in over a decade.

Trendlines

Despite having more than 100 cases to study, one of the most difficult tasks for this research is to highlight trends, in concrete terms, in order to develop actionable policy recommendations. The fact that the Islamic State’s approach towards ideological, territorial and propaganda expansion is backed by dividing its operations into what can be examined as a two-sphere approach. The first is the theologically backed hierarchical structure of the Islamic State, where the Sharia interpretations reign supreme and a member’s movement within the hierarchy depends on both their religious and organisational skills. The second is propaganda approaching those who may not have completely religious reasons, but the said paraphernalia appeals as much to a person’s religious beliefs as to irrational whims, from boredom to the need to do something with life.

The patterns observed in the Indian cases had a few peculiar features that other geographies around the world, particularly Europe, did not have in common. First, all cases are those of Indian citizens. Europe, for its part, has seen a mix of two types of radicals who have committed attacks: those fighters that travelled to Iraq or Syria to fight for ISIS and made their way back; and Iraqis, Syrians or others who were ISIS but made it into Europe as part of the refugee influx (a strategy advertised by ISIS propaganda machines). While Indians suspected of joining ISIS have previously been arrested at Indian airports, none of the cases studied highlight individuals committing terror attacks in the name of the Islamic State after travelling back into India from the Middle East.

The internet has been the predominant driver of the radicalisation process, and this has been a global trend barring the Middle East region. The people who made the choice of subscribing to the Islamic State’s call can be seen as individuals who were in two frameworks—they were either already radicalised whether due to international or domestic events, or they were on the cusp of radicalisation and were convinced by the pro-ISIS online propaganda machinery that this was the correct step to make as a Muslim.

While the very idea of the ‘caliphate’ is the crowd puller, so to speak, for foreign fighters, the ambition for most is to be frontline fighters in the caliphate. Including Indian cases, not many examples of foreigners travelling to Iraq or Syria to be part of ideological nurturing of the group have come to light, with enforcing the military aspect seemingly being the major draw. For example, cases such as that of Areeb Majid from Maharashtra as discussed earlier shines the light on the difference between expectation and reality. Majid’s experience was contrary to what others were getting, and while it is difficult to establish empirical support for this hypothesis, the fact that he did not get to experience the war front as a representative and fighter of the Islamic State may have led him to feel humiliated by not just ISIS but his peers as well. ISIS fighters were kept together in groups of 20 each, while they trained for acts such as assassinations, beheadings, and executions. Majid was clearly not part of this group, and such an outcome may have led to his surrender on the Turkish border and eventual deportation to India where he faced trial. However, the other three young men who travelled with Majid and were killed in Syria over the past years of war, seemingly did manage to take their place within the ranks of ISIS.

The use of internet as well has had changing and diverse reactions, however, more than consumption of propaganda materials, it is in fact the ease of use of the World Wide Web as a communications tool that poses a bigger challenge for authorities. In most Indian cases, social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter have provided the initial platform for the commonality of radicalisation to find people with similar intentions, or at least inclinations towards ideological or practical advances. Some of the most common discussions pro-ISIS people in India had not just with people from India or South Asia, but all over the world, was in fact to inquire about how to plan the final move to the caliphate.

These plans had neither geographical strategy nor leadership. While the likes of Shafi Armar tried to bring some order into the interest emitting from Indians on joining ISIS, little success was achieved. This ad-hoc approach observed is common to almost all the cases studied for this exercise. The traction of social media for potential Indian recruits also ran into roadblocks with the people themselves, with little to no institutional practical approach given by ISIS recruiters online beyond pedestrian advice on purchasing weapons, moving money, and others. In some cases, individuals took it upon themselves to form small groups and train themselves a la guerilla outfit. In one particular case in the state of Telangana, one Naser Mohamed from Tamil Nadu attempted to form a pro-ISIS module using a collaboration of social media and mobile phones (with various numbers) which caught the eye of Armar as well. Naser formed a group called Junood-ul-Khilafa-Fil-Hind which held intra-state meetings between five people from states such as Telangana, Kerala, Uttar Pradesh. The first meeting took place in the forests of Tumkur, Karnataka. Forests were chosen due to their obscurity and the availability of space to build training areas where the recruits could stimulate attacking targets handpicked for them by Armar. This cell was broken only a few months after its formation in 2015.

The approach by ISIS’ online mujahids towards Indian recruits has the uncharacteristic stamp of disorganisation and poor planning and approach. Two thoughts can be drawn here—one being that India was simply a much more difficult environment to break through, with majority of Muslims shunning the ISIS ideology and methods of its approach towards Sharia, and second that most radical Islamist thinking within India has connotations to regional issues and conflicts. This analogy can be argued and sustained despite the fact that the states and cases studied here were predominantly from southern Indian states, with Kerala leading the way. The cases within Kerala, barring one or two, had a connection with the Middle East one way or the other, such as locals coming into contact with returning Indians and getting informed about the Islamic State. This availability of information was not necessarily in support of ISIS, and could well have been simply an explanation of what is going on in the region or plainly against the narrative of supporting ISIS that said person may have come across during his or her time there. As per analysis of these cases, a person’s understanding of their own personal status of thought, or where they stood between thinking and action, played a significant role on their eventual perception, or clarity, of the Islamic State.[xxxiv]

Decoding the Future Threat

Today, analysing the threat posed by ISIS comes from the fact that it is next to impossible to quantify it. While the so-called caliphate has lost next to almost all territory it once held, the terror group has now institutionalised itself not only in the Middle East, but in regions of Africa, the Philippines and most importantly, Afghanistan.

The fall of ISIS is a misnomer, rushing into a conclusion backed by the fact that Western coalition and Russian air campaigns in Syria have indeed managed to disband much of the caliphate. Yet that does not translate into the “end of ISIS”. While Iraq has handled its post-ISIS situation well for now, Syria, on the other hand is in complete chaos. While fighting and dismantling ISIS from territory had become the singular task of many rebel groups partaking in the civil war, the geographical destruction of the caliphate out of ISIS hands meant these groups have now turned to serve their own self-interests.

One of the main questions raised during this period was what happens with the remaining ISIS fighters, specifically the foreigners who travelled from across the world to help govern the new proto-state during 2014-15. This has been the most prominent argument from Moscow on explaining its involvement in the Syrian war. “Terrorists should be eliminated where they are. One of the major reasons why Russia is in Syria, there are many questions why Russia is in Syria. The major reason why is because those terrorists who are in Syria have intentions to go to Russia, to Trans-Caucasus, to Central Asia. We better eliminate them there, not in places where they want to go. So, don’t let them go, eliminate them where they are,” a top Russian leader said, highlighting the justification offered on intervening in the conflict.[xxxv]

However, there are two main fronts of ISIS that are going to be critical for both ISIS and the effects it will have as a terror group. First, the fact that the Syrian conflict has now moved away from fighting ISIS to other intra-regional, intra-jihadist and long existing sectarian fractures. The destruction of the caliphate acted as the nucleus towards which most actors of the Syrian conflict gravitated, now, having pushed ISIS away from a proto-state to a guerilla outfit, the Syrian war has become a host of miniature wars being fought in a broader framework. This, however, also gives the likes of ISIS an opportunity to regather their strategies and orchestrate a rebound. The probability of this happening is not farfetched; political vacuum offers a good environment for terror movements to bounce back on. This has been witnessed before in Afghanistan, as post-9/11 American bombings pushed Al Qaeda and Taliban into the Tora Bora mountains, and the Afghan landscape is today once again less in control of the civilian government in Kabul and more in favour of the Taliban and other local warlords.[xxxvi]

For India, the rise and success of ISKP in Afghanistan, and in some instances Pakistan as well, is a worrying sign. After the destruction of the caliphate’s self-declared capital Raqqa, the most powerful, well organised and increasingly operationally successful clone seems to have been set up in Afghanistan. To understand ISKP and its potential influence on jihad in India, the divisions within the organisation from the context of Afghanistan’s domestic politics and its relations with Islamabad need to be contextualised. While the research on ISKP is so far limited, some critical work published by the likes of Antonio Giustozzi at the Centre for Research and Policy Analysis in Kabul highlight the levels of division within the ISKP framework.

ISKP has regularly claimed major terror attacks killing dozens of people in the Afghan capital. This has raised questions on how a relatively new group is capable of making such large advances in a short period of time, specifically when the likes of the Taliban and Al Qaeda claim much of the political and military space.

The ISKP feeds off as an entity from various regional sources and in all likelihood has the support of certain state actors at least, without which it could not have succeeded in penetrating Kabul and Taliban and Al Qaeda strongholds. Giustozzi, in his paper titled ‘Taliban & Islamic State: Enemies or Brothers in Jihad?’, highlights the politics of ISKP that played out in the summer of 2017 when the organisation went through a split between former Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT) commander Aslam Farooqi and former Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) commander Moawiya battled over the position of governor of Khorasan. The Central Asian outfit, after a vote that went in favour of Farooqi, seemingly built a narrative that the former LeT commander still held on to links with the Pakistani state, including getting funding from the ISI.[xxxvii]

LeT, of course, is a prominent tool of Pakistani policy on Kashmir and has largely been deployed on the country’s restive borders with India. While no empirical evidence was made available for this paper, trends of ISI along with a well-funded ISKP can try to infiltrate the second-strain of jihad in the valley, which is largely religious and not political. The ‘second strain’, while dormant in much of the history of extremism in Kashmir, is finding its feet amidst all the chaos. The notion of ‘fighting for Islam’ and not ‘Pakistan’ or ‘Kashmir’ has appeared in various narratives, including nationalist militant groups from Pakistan. While these views do not have much space within existing jihadist groups in Kashmir, they do hew well with narratives peddled by the likes of ISIS. For example, the case of Eisa Fazili as mentioned earlier, had seeds of this particular narrative. After his funeral in Srinagar, one of Fazili’s friends on social media highlighted that he used to get angry whenever someone criticised ISIS continuing to blame the Wahabi preachers that misled him, the Tehreeki leaders that encouraged him and the “careless” friends and relatives that let him become what he was.[xxxviii]

The alignment towards fighting for Islam and not for Pakistan or azaadi in the valley will, in fact, give more leverage and space to the likes of Al Qaeda and ISIS. Despite the global marketing appeal that ISIS wields, it is in fact Al Qaeda that may benefit more, in Kashmir, than its new global counterpart. While ISIS currently has the global narrative on its side, Al Qaeda with its history and more institutionalised and targeted agendas could be poised to become a larger threat in a bid to outpace ISIS. According to a new report by the Council on Foreign Relations, Al Qaeda has been restructuring and reorganising itself in the wake of the rise and fall of ISIS. Of course, ISIS itself came out of the ashes of Al Qaeda in Iraq, however the post-Bin Laden era saw Zawahiri push for a stronger foothold in Syria and sent an experienced Syrian jihadist named Abu Muhammed al-Julani to establish Jabhat al-Nusra. The resurgence of Al Qaeda is seen as a byproduct of the Arab Spring, with the terror group being labelled as one of the big winners emerging from the failed popular movement.

According to the same report, India, Afghanistan and Pakistan account for more than 800 Al Qaeda operatives while, perhaps more consequentially as an area that gets sidelined on both analysis and data front, Bangladesh accounts for more than 300 operatives. Al Qaeda’s footprint—despite the Dhaka attacks in July 2016 claimed by ISIS, which killed 29 people including 18 foreigners—is deeper with a stronger sense of longevity and institution. The organisation has survived and strengthened its core despite decades-long military interventions by Western forces in the terror group’s traditional bastions and new ones as well such as in Libya.[xxxix] The battle of influence, wits and narrative between Al Qaeda and ISIS is one that is being fought in-between blurred lines, and claims and counter-claims by both may become a common irritant in tracking Islamist attacks around the world.

Conclusion

A question often asked by scholars studying West Asia and Islamist terrorism is how India, with 14.2 percent of its population being Muslim, have such few cases of pro-ISIS activities, and how that narrates to threat perceptions and counter-terrorism strategies of the Indian state.

Understanding the influence of ISIS on Indian jihadist discourse and on general variables by studying the few cases we have seen brings up two main streams for future discourse. First, a deep-dive into individual cases, their histories, community connections and habits as single entities, which is a traditional approach to counter-terror theories still remains the most effective way to decode a threat as dynamic as ISIS. Even though, as this paper discussed, there is a pattern of group work between potential ISIS recruits mostly due to the ease of access to communication technologies and the internet, most answers within the said group dynamic tend to lie with the ability to identify the leader or the individual most vibrant and active in propagating ideology or travel to the caliphate and nip the bud from there.

The cases studied in this exercise offered both interesting information and access into the intent and mindset of the people willing to join ISIS from India. They also showed the challenges to build counter-narratives to such ad-hoc radicalisation which is less relatable and different from previous organisations such as Indian Mujahideen, which were inherently local, or insurgencies in Kashmir that had localised political aims as well.

Such outcomes make it difficult to put the influence of ISIS on Indian society and polity under any specific brackets, and do not allow forming specific conclusions out of the exercise. This, in turn, both highlights the problematic areas and challenges that policy-makers have faced globally in the fight against ISIS. While some European countries were able to better equip themselves at a faster pace due to the refugee rush towards their borders, countries farther away from exposure to ISIS had the luxury of slow observations and regional threat-based assessments, often only on a case-to-case basis. This also led to losing sight of just how important ISIS’ weaponisation of the internet was. In India’s case, policies, capacity and technologies are still catching up to get ahead of these threats.

Policy practitioners need to approach, not just the threat of ISIS, but new terror and insurgency threats alike, on two main fronts. First is technology. While in most cases it is the state that is almost always far ahead in technological superiority, it is the selective use of said technologies and their narrative-led intent that often is enough to cause public scare and gain global media attention for a said violent outfit. The threat perceptions are much beyond the physical aspects of counter-terrorism, human intelligence, and military force. Open-source intelligence (OSNIT), cyber security, battle of perceptions, narratives, fake news and even emotions, all have the potential of manipulation using digital information and access. These challenges are today common between policy-makers, law enforcement agencies and scholars alike.

The threat ISIS poses to India, and South Asia in general, is as real as it is for any other major region or state. This does not come from an organisational pattern from the so-called caliphate or al-Baghdadi himself, but the ecosystem that has been created that allows open-source access to ISIS as a brand which is a powerful enough tool to make global headlines at the smallest of an incident, committed even by a petty criminal. The internet remains the main propagator of pro-ISIS activities, and will continue to be one even after a complete “defeat” of the so-called Islamic State. Building capacity to tackle this is the biggest challenge facing India, South Asia and the rest of the world collectively. It is no longer only about ISIS, but new trends in terrorism that will be replicated by others in the future.

ENDNOTES

[i] Kabir Taneja, “The Fall of ISIS and its Implications for South Asia”, Observer Research Foundation, January 4, 2018.

[ii] Charlie Winter and Haroro J. Ingram, “Terror, Online and Off: Recent Trends in Islamic State Propaganda Operations”, War On The Rocks, March 2, 2018.

[iii] Paul Mcleary, “SitRep: ISIS 2.0 On The Way”, Foreign Policy, October 18, 2017.

[iv] Much of the first-hand research used for this paper was done using the tracker project, “Tracking ISIS’ Influence in India”, Observer Research Foundation.

[v] “External Affairs Minister’s Statement at the International Conference on Syria (Geneva-II)”, Ministry of External Affairs, 2014.

[vi] Ammar Abdulhamid, “What the Failure of Geneva Talks Mean”, Lawfare/Brookings, April 25, 2016.

[vii] Zakir Hussain, “How ISIS’ Long Reach Has Affected Singapore”, Straits Times, July 16, 2017.

[viii] National Investigation Agency Press Release, Charge-Sheet filed in RC-03/2017/NIA/DLI (ISIS/Daesh Chennai Case), March, 2018.

[ix] Vicky Nanjappa, “ISIS in Tamil Nadu: NIA secures arrest of key accused”, One India, February 13, 2018.

[x] “State Department Terrorist Designations of ISIS Affiliates and Senior Leaders”, U.S. Department of State Press Release, February 27, 2018, accessed March 2018.

[xi] Joyeeta Bhattacharjee, “The Face Of Terror In Bangladesh”, The Pioneer, February 23, 2018.

[xii] Matthew Levitt, “The Zarqawi Node in the Terror Matrix”, The Washington Institute, February 6, 2003.

[xiii] Excerpt from charge sheet accessed by ORF on Mosiuddin Sulaiman.

[xiv] Excerpt from charge sheet accessed by ORF with information on Mohammed Shafi Armar.

[xv] Harleen K. Gambhir, “Dabiq: The Strategic Messaging of the Islamic State”, Institute for the Study of War (ISW), August 15, 2014.

[xvi] “Number of monthly active WhatsApp users in India from August 2013 to February 2017 (in millions)”, Statista: The Statistics Portal, accessed March 14, 2018.

[xvii] Lewis W. Dickson, “Lone Wolf Terrorism – A Case Study: The Radicalization Process Of A Continually Investigated & Islamic State Inspired Lone Wolf Terrorist” (PhD diss., Malmo University, 2015), 7.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Ramon Spaaji, Understanding Lone Wolf Terrorism (New York: Springer, 2012), 34.

[xx] “Mobilization to Violence (Terrorism) Research”, Canadian Security Intelligence Service, accessed February 27, 2018, .

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Ralph Ellis and Saeed Ahmed, “Europe’s Most-Wanted Man Captured”, CNN, March 19, 2016.

[xxiii] “Bhopal-Ujjain Train Blast: NIA Chargesheets Four Men Linked To ISIS”, Hindustan Times, August 8, 2017.

[xxiv] Ashish Pandey, “Lucknow Siege: How 4 States – UP, Telangana, MP, Kerala – Worked Together To Bust ISIS Khurasan Module”, India Today, March 8, 2017.

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] Excerpt from a charge sheet accessed by ORF highlighting anti-VHP communications between pro-ISIS people, https://www.scribd.com/ document/379380787/Vhp-Pisis.

[xxvii] Data from www.jihadology.net, academic database on jihad and Islamist groups banned in India.

[xxviii] Haroro J Ingram, “Islamic State’s English-language Magazines, 2014 – 2017: Trends and Implications CT-VE Strategic Communications”, International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, March 12, 2018.

[xxix] Kabir Taneja, “Islamic State Merits High Caution But Not Careless Alarmism in Kashmir”, Scroll.in, October 20, 2014.

[xxx] Excerpt from charge sheet accessed by ORF on Mohammed Sirajuddin case.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] Accessed via Telegram by ORF.

[xxxiii] Neeta Sharma, “Zakir Musa Tops New List of 5 Most Wanted Terrorists In Kashmir Valley”, NDTV, October 5, 2017.

[xxxiv] All trends are outcomes of the ISIS tracker study. “Tracking ISIS’ Influence in India”, Observer Research Foundation.

[xxxv] Dr. Vyacheslay Nikonov Speaking on Terrorism during the Raisina Dialogue, Observer Research Foundation, May 7, 2018.

[xxxvi] Quarterly Report to the US Congress, prepared by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, October 30, 2017.

[xxxvii] Dr. Antonio Giustozzi, “Taliban and Islamic State: Enemies or Brothers in Jihad?”, Centre for Research & Policy Analysis, December 15, 2017.

[xxxviii] Rayan Naqash, “From Srinagar, A New Crop Of Militants Who Kill And Die In The Name Of Religion, Not Politics”, Scroll.in, July 9, 2018.

[xxxix] Declan Walsh and Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Strikes Qaeda Target in Southern Libya, Expanding Shadow War There”, The New York Times, March 25, 2018.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV