This is the 118th article in the series —

This is the 118th article in the series — The China Chronicles.

Read the articles here.

The education sector seems to be in the crosshairs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). New regulations disallow any company that teaches course content listed in the school curriculum to list on overseas bourses, having foreign investment or corner huge profits. In response, the stocks prices of three online education companies listed on New York Stock Exchange plummeted by over 65 percent. The virtual-tutoring business has been one of China’s fastest-growing sectors in recent years, with as many as 27 initial public offerings (IPO) since 2019.

Through business ventures, several entrepreneurs have been able to capitalise on the social institution of ‘bǔkè’ (补课) where parents push their sole progeny (as a result of the one-child policy, which has now been revised) to enrol for extra study to improve scores.

In June, the then Education Minister, Chen Baosheng, announced that a new department would be established to oversee ‘out-of-school education’ programmes. This department will formulate standards for course content and length of online and offline training programmes, set the standards for qualifications of educators and regulate the tuition fees charged. Through business ventures, several entrepreneurs have been able to capitalise on the social institution of ‘bǔkè’ (补课) where parents push their sole progeny (as a result of the one-child policy, which has now been revised) to enrol for extra study to improve scores. The competition for entrance tests for admissions to senior high schools and colleges is intense. Even the state-run media has singled out the such firms for overcharging. Take the case of Zuoyebang, which literally means ‘get help with homework’, streams online classes to over 170 million subscribers every month, counts Alibaba Group Holding as an investor. Buoyed with its success in the Chinese market, the firm had been contemplating a US $500 million IPO in the United States (US). Early on into his term as the leader of China, Xi Jinping had his gaze on the education sector, especially such training organisations. He had called out such practices as detrimental to the growth of students due to their “potential to disrupt the teaching routine in schools,” and for “loading parents with a financial burden.” His prescription for the sector was tighter regulation and getting these training companies to put their efforts into imparting guidance on extra-curricular activities and hobbies.

This has prompted questions about why China was harming the goose that literally lays golden eggs. The CCP seems to be weighing trade-offs between pushing its social programme and economic growth.

While nations in East Asia grew rich on account of such policies, a “virtuous circle” was at play since emphasis on women’s education led to a decrease in the size of families.

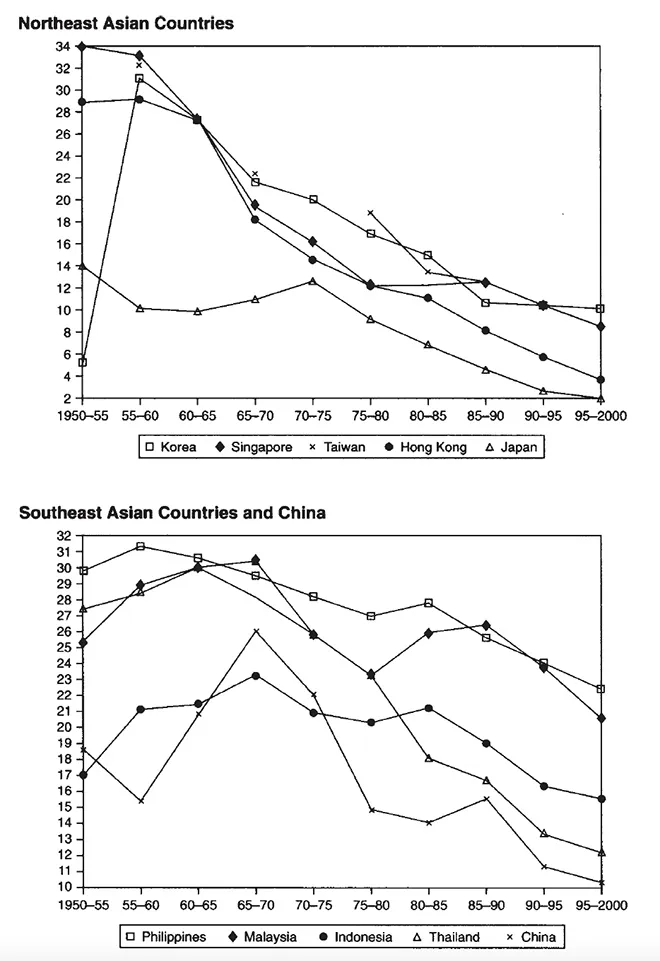

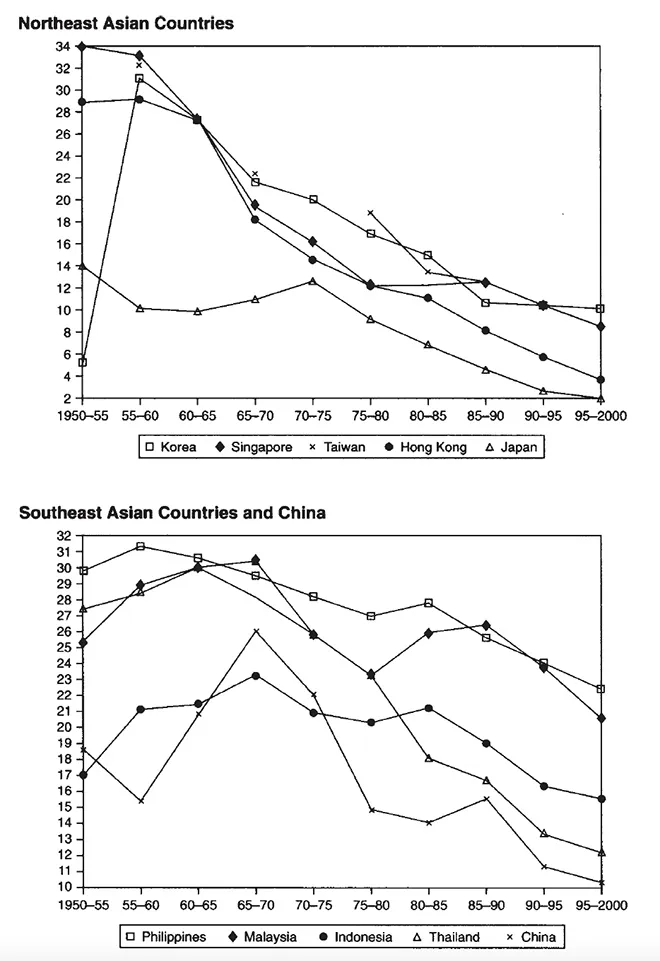

One of the reasons behind the increasing scrutiny of the education sector may be related to China’s population question. Early on during its development trajectory, China borrowed the export-driven development strategy of East Asian nations. While nations in East Asia grew rich on account of such policies, a “virtuous circle” was at play since emphasis on women’s education led to a decrease in the size of families. On the other hand, Mao Zedong’s philosophy that with more “people meant China would be stronger” precluded the nation from developing voluntary family-planning initiatives like in Taiwan or South Korea (see table on ‘natural increase rate’ in China and rest of East Asia).

Source: ‘Behind East Asian Growth’ ed. Henry S. Rowen

Source: ‘Behind East Asian Growth’ ed. Henry S. Rowen

Since embarking upon economic reforms in the late 1970s, Deng Xiaoping introduced the one-child policy to curb China’s rapidly growing population, which was estimated at 970 million at the time. The CCP’s thinking was that the one-child norm would alleviate challenges of limited natural resources caused by a burgeoning population, raise living standards and ensure that the gains made due to opening up of the economy would be shared by a limited pool of people. Over three decades later, China replaced it with a two-child limit, and this year it announced that couples would be permitted to have up to three children, after data gleaned from the census showed a slowing down in birth rates. The 2020 Census revealed that China’s population rose 1.412 from 1.4 billion in 2019; the fertility rate was 1.3 children per woman, well below the ‘replacement level’ of 2.1 required for a stable population. The CCP is apprehensive that a declining labour force will dent the country’s long-term growth. However, a couple’s family planning goals not always be in sync with the CCP’s diktats. While Deng told the Chinese “it was glorious to get rich,” Jack Ma revealed the secret to prosperity — the ‘9-9-6’ culture, where professionals toil 6 days a week from 9 am to 9 pm. Many young professionals surmise that it would be rewarding for them to adopt such an ethic since it worked for the Alibaba founder, but the flipside is that they either defer or put off family planning decisions. Even as China was relaxing population capping, there were debates on the cost of raising a child, a survey in May 2021 revealed that faced with rising debt worries and living costs, more and more millennials in China were putting off having children to circumvent the financial burden. Some aggregates placed the cost of raising a child in China at around RMB 1.99 million (approximately US $300,000). Efforts are being made at a policy-level to address the problem. In an ironic twist, Panzhihua, a city in Sichuan province that is Deng’s birthplace, is one of the first urban centres to dole out benefits to families who have a second or third child. A household will receive RMB 500 per child as a financial inventive, which will cease once he/she turns 3. While education in China is free for children up to the age of 15 years, Xi’s crackdown is directed at ensuring that at least excessive consumerism seen in America where education can be bought and sold does not become a staple in China. Thereby, also ensuring that tech start-ups in education who boasted of their net worth in billions of dollars, do not profit from parents’ anxieties and social institutions like ‘bǔkè’. In part, it may also relieve the burden that discourages couples from having children at all.

Even as China was relaxing population capping, there were debates on the cost of raising a child.

Two more factors that contribute to Xi leaning on the education sector are the CCP’s current priority themes — poverty alleviation and national security. This year as the CCP marks the centenary of its birth, it has showcased “lifting 850 million people” out of poverty as a major achievement. The issue of income disparity has niggled the CCP, and in October 2020, the issue once again came up at the CCP’s Plenum — an annual gathering of top leaders that discusses means to improve governance. China has expanded access to higher education since the 1990s, with the figure of students admitted to universities each year reaching nearly 10 million. The current system of online education start-ups, which give an edge to students whose parents have deep pockets, have skewed the pitch for the poor. Aspirants from underprivileged backgrounds living in the hinterland strain to compete with those from affluent backgrounds, with barely 0.3 percent of rural students make it to the 1 percent of China’s top universities. Xi, who as a teenager was banished to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution understands this, and is perhaps trying to remodel education to make it fair to the poor.

National security considerations too merit closer examination of the education enterprises. Xi sees national security as the foundation of economic development and social stability; in this endeavour, he seeks to construct a “national security framework” that extends to “all aspects of the work of the CCP and the country.” Xi wants campuses and varsities to follow the lead of his own alma mater, Tsinghua, in producing students who are both ‘red and experts’ meaning individuals who will owe allegiance to the CCP and are professionally competent. Hence, the CCP has reasons to fear the presence of foreign capital in a crucial sector like education as its next generation is susceptible to influence and penetration by forces hostile to the CCP. Whatever the motives of the CCP may be, its impulse to control society has mostly led to unexpected outcomes as evidenced in the fall-out of the ‘one-child’ policy. One wonders whether the clamping down on start-ups will really benefit parents or may lead to them engaging tutors privately, which may prove to be costlier. Seeing the adverse reaction, the CCP has tried to reassure investors by taking a line from Mao’s couplets ‘range far your eye over long vistas’. It expects them to take a long-term view of China. One must bear in mind that only a robust system, which protects rights and has predictable rules, can attract capital. China’s system where laws are a means merely to meet the CCP’s governing agenda will hurt it in the long haul.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This is the 118th article in the series — The China Chronicles.

Read the articles

This is the 118th article in the series — The China Chronicles.

Read the articles

PREV

PREV