This essay is part of the series “Reimaging Education | International Day of Education 2024”.

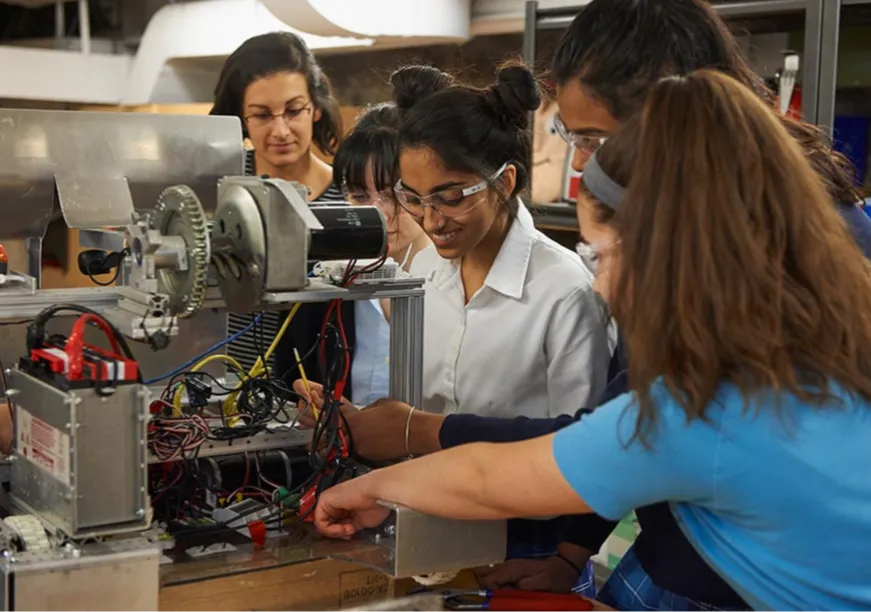

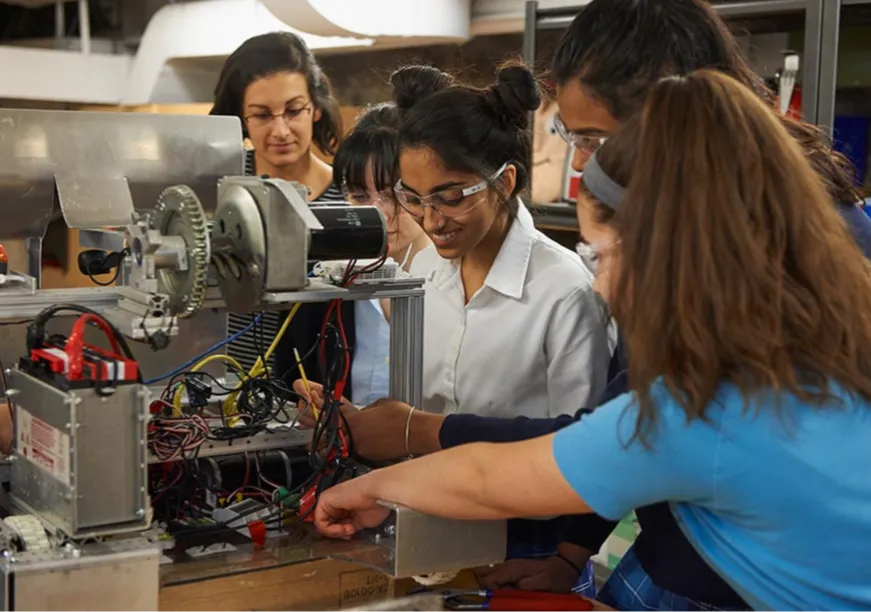

The widespread adoption of technology in everyday life has made STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education a prerequisite for achieving sustainable and inclusive growth, and social well-being. Equal access and participation in STEM for women and girls is key to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. However, progress on SDG 4 (to ensure equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all) and SDG 5 (to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls), in STEM sectors has been slow.

The underrepresentation of women in STEM is common in every region of the world. A 2020 report by the World Bank on global trends in the participation of women and girls in STEM found that even though graduation rates are higher among women than men, women are less likely to undertake studies in STEM fields, particularly engineering, Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and physics. Women who study STEM fields are less likely to enter into STEM careers and exit these careers earlier than male peers. Women in STEM fields publish less and are likely to be underpaid. Women comprised 29.2 percent of the STEM workforce in 146 nations evaluated in the Global Gender Gap Report (2023), even though women made up 49.3 percent or almost half of the total employment across non-STEM occupations.

Women who study STEM fields are less likely to enter into STEM careers and exit these careers earlier than male peers.

An interesting paradox that recurs globally is that the gender gap in STEM widens with the increase in country income and gender equality, according to the World Bank report. While women in low-income countries are 7 percentage points less likely than men to enrol in tertiary programmes in engineering, manufacturing, and construction, the gaps widen to 15 and 17 percentage points respectively, in upper-middle-income and high-income countries. Keeping with the trend, Myanmar, Azerbaijan, Thailand, and Georgia are among the countries with the highest number of female researchers.

India has the highest number of STEM graduates in the world, and the number of women choosing STEM courses has been steadily increasing, even though India lags in women’s participation in the STEM workforce. A great number of women drop out as they shift from STEM education into careers.

According to the All India Survey on Higher Education by the Ministry of Education, which tracks enrolment in graduation--, post-graduation-, and PhD-level programmes, the number of female graduates rose from 38.4 percent in 2014-15 to 42.6 percent in 2021-22. Quite simply, India has the highest number of female STEM graduates in the world, a vast and relatively untapped human capital resource.

In relative terms, the percentage of women who opt for STEM education is higher than in most countries. Data by the World Bank show that India’s share of female graduates in STEM at 42.7 percent in 2018, was higher than comparable data available for the US at 34 percent in 2016, Australia at 32.1 percent in 2017, and Germany at 27.6 percent in 2017.

Policies that support women in STEM

The gender inequality in STEM has been addressed in several intergovernmental forums, starting with the Beijing Declaration by the United Nations. The underrepresentation of women and girls in STEM has been an ongoing concern for policymakers in India. National assessments have been undertaken to identify the reasons for the lower participation of women and to take corrective action. A recent assessment by the government showed India has 18.6 percent of women researchers in R&D activities and attributed the lower participation to familial responsibility faced by women which leads to career breaks and prolonged absence from work.

The gender inequality in STEM has been addressed in several intergovernmental forums, starting with the Beijing Declaration by the United Nations.

Several policies seek to address these issues. The Science, Technology, and Innovation (STI) Policy 2013, promotes gender parity in STI activities. The Department of Science and Technology has different programmes under the scheme ‘Women in Science and Engineering-KIRAN (WISE-KIRAN)’, like the ‘Women Scientist Scheme’ to encourage women to return to the workforce after career breaks, and ‘Consolidation of University Research through Innovation and Excellence in Women Universities (CURIE)’ programme for development of infrastructure and research facilities for women.

The Gender Advancement for Transforming Institutions (GATI) programme aims to assess gender inequality and transform institutions towards gender-sensitive approaches. The SERB-POWER (Promoting Opportunities for Women in Exploratory Research) addresses lower participation of women scientists in research activities through grants and fellowships. The Vigyan Jyoti programme encourages high school girl students to opt for STEM focusing on rural areas.

The Indian Institutes of Technology have driven up female enrolment in recent years by introducing additional seats. The All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) has been running two schemes, the Pragati Scholarship and the TechSaksham Programme for women, which enhances their employability in the labour market.

Many of these programmes have been impactful in driving up the numbers of women in STEM education, but have not been able to address the issues they face in the workforce.

Addressing the gender gap in the STEM workforce

Despite the high proportion of female STEM graduates, women account for less than a third of the STEM workforce in India at 27 percent, according to World Bank data. This phenomenon of underrepresentation of women, common to many countries, has been defined as the “leaky pipeline”, which is to say that despite the ability to succeed in STEM careers, women tend to not pursue or gradually drop out of the workforce.

Aside from individual choices that women may make due to domestic and care burdens, they face biases, stereotypes, and systemic barriers, at home and workplaces. These biases also affect STEM products and innovations, as has been widely documented.

Despite the high proportion of female STEM graduates, women account for less than a third of the STEM workforce in India at 27 percent, according to World Bank data.

To support women to enter and remain in the field, fighting cultural biases by raising awareness is necessary along with policy interventions. Aside from scholarships and programmes that support their education, workplaces need to promote women through training and mentoring initiatives and investments in providing care infrastructure and leave-related policies.

Several alliances and initiatives have been newly launched to increase the number of women in STEM education and workforce in India. India is already a global STEM leader in the making. All it needs is to ensure that its female STEM graduates are retained in the workforce.

Sunaina Kumar is a Senior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV