-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Globalisation has always been the main theme of the annual conference in Davos, Switzerland every January and it has been zealously advocated by the developed countries. But today, it is under threat, according to reports from Davos 2017. And strangely the defender of globalisation today is Chinese President Xi Jing Ping and not any longer the US, the champion of freed trade earlier.

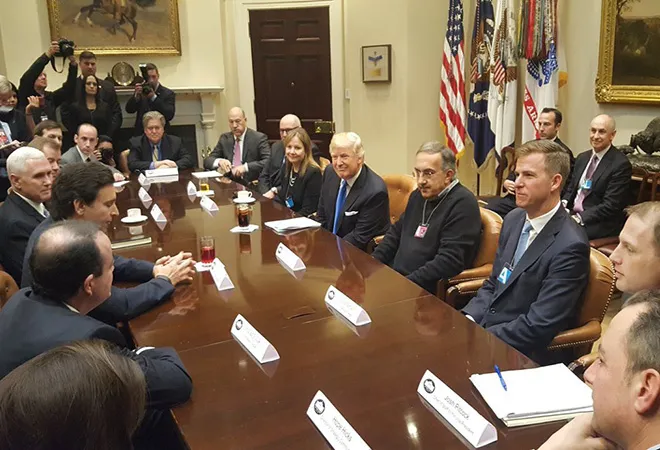

With Brexit in Britain and US President Donald Trump’s vehement objections against outsourcing by American manufacturers, there has been much discussion recently about the fate of globalisation. Is it going to be reversed in the next few years and will the US and other developed countries retreat behind protectionist walls?

Globalisation has benefited the rich and the top layers of society in most countries. In the past few years, especially after the Global Financial crisis of 2008, however a lot has been written about the rising inequalities between countries and within countries. Recently, Oxfam reported that just 8 men from the industrialised world had more wealth than half of the global population of more than 3.6 billion. Rising inequality of incomes between regions in Britain and between the rich and the middle classes as well as the perception that immigrants are taking away all the new jobs led to Brexit in June 2016. It is yet to be seen whether Brexit will solve Britain’s economic and social problems.

Similarly, Trump has also said that he will make America great again by creating and bringing back jobs in the US and he will put a stop to all outsourcing of services which will hit India. But this is an unrealistic short term view considering the past global trends. As long as costs keep rising, it is economically better for American companies to keep prices down by outsourcing parts of their production or the entire product to cheaper labour-intensive destinations which are located in developing countries. The US garment trade, for example, has flourished by outsourcing to Bangladesh and many well-known branded goods are also being outsourced to China and other countries in Asia where wages are lower. Otherwise, consumers would have to pay higher prices for products in the US and they will refuse to do so. American consumer spending will shrink and this will affect adversely its GDP growth.

Globalisation has taken place via trade through several millennia. Ancient India exported to Europe beautiful artefacts, semi-precious stones and textiles, to Africa, cloth and beads. In the late Eighteenth and mid Nineteenth century France, Indian Kashmiri shawls were a rage and every society lady possessed one. But its trade stopped due to the Franco Prussian War in 1870-71. Globalisation in the form of migration took place in the 18th and 19th centuries on a massive scale to the New World from Europe. US received 32.6 million of Europeans from 1800s to 1990s. Indians also went as indentured labour to Fiji, South America and Africa.

But the real globalisation in the form of free trade was initiated in the 19th century after the industrial revolution by the repeal of the Corn Laws in England in 1840s and corn was allowed to be imported into Britain to overcome a shortage. There has been an increase in world trade and finance ever since, though there have been highs and lows.

Globalisation suffered a setback during the great Depression of the 1930s when many countries turned protectionist. But after the Second World War, the US became the champion of Free Trade and the pace of globalisation picked up since the end of the Cold War. It is human nature to want variety and change. During the Cold War, the Soviet Bloc was isolated from global trade and commerce. The Russians as a result were craving for western consumer goods and lifestyle till the Soviet Union collapsed in 1990. In India also, during the protectionist era that ended in 1991, people hungrily bought foreign goods from abroad for their use in India. Now there is hardly anything which is not available in India.

In the last two decades, China emerged as the biggest producer of consumer goods. After it joined the WTO in 2001, China became supplier of cheap but good quality products all over the world, including India. The US was flooded with cheap imports from China which helped the US to keep inflation down. American companies established factories in China and goods were transported back home and sold at much higher retail prices, fattening the corporate wallets and increasing the profits of transnational corporations.

Read Also | < style="color: #960f0f">The world system going through a serious churn

American factories in mid-West, meanwhile, closed down as production was shifted to Mexico and Asian countries where labour, whose living standards was much lower, worked at lower wages, for longer hours and with fewer holidays than their American counterpart. The US companies found to their advantage that Asian and Chinese labour was willing to work at a fraction of the cost of American labour.

Since the global financial crisis, globalisation ran into roadblocks. According to US-based Peterson Institute, the era of globalisation was not accompanied by a general commitment to liberalising flows of people and it mainly focused on trade and finance. Since the global financial crisis, the ratios of world trade to output have been flat, making this the longest period of such stagnation since World War II. The volume of world trade has stagnated recently between 2015 and March 2016 even though the world economy has continued to grow. Global trade grew at 1.7 per cent and is likely to slow down further in 2017. Inflows of FDI have remained well below 3.3 percent of world output attained in 2007, though the stock continues to rise albeit slowly relative to output.

Cross border financial capital -- both inflows and outflows -- are growing more slowly and are down significantly in absolute terms from 2009 levels. It is mainly cross border bank lending and borrowing that have fallen. Regulations have played a part in curtailing cross border business as it affected the value of national currencies. But cross border lending and borrowing through stock and bond market remains as before the financial crisis.

Investment and spending has fallen sharply everywhere since the global financial crisis. Investment spending in the US is trade intensive and relies disproportionately on a relatively small handful of producers like Germany for technologically sophisticated products. Increased spending on infrastructure by the governments will boost investment and growth directly. Hence growth promoting policies are needed in the US and Trump wants to spend on infrastructure.

Due to protectionist policies in many parts of the world, trade liberalisation on a multilateral basis has also stalled. WTO’s Doha Round remains in the cold storage. Could this signal a reversal of globalisation? According to Barry Eichengreen, trade has slowed because GDP growth has slowed in many countries and not vice versa. Slow trade growth in the world reflects China’s economic deceleration. Until 2011, China was growing at double digit rates and exports and imports were growing very fast. China’s GDP growth has slowed in recent years leading to slower growth of Chinese trade. The other engine of world trade has been supply chains. Trade in parts and components benefited from falling transport costs, reflecting containerisation and related advances in logistics. But efficiency in shipping is unlikely to improve faster than efficiency of what is being shipped, slowing trade.

Yet, today Trump’s denigrating WTO and trashing NAFTA and wanting to build a wall between Mexico and US and imposing punitive tariffs on Chinese imports to US reflect his disdain for globalisation, but going it alone will not help US or any other country. Globalisation is bound to continue even if there are more protectionist measures taken by Trump. It may, however, mean that China will take a leadership role in global trade and investment at least among developing countries and Asia in particular. China is already outsourcing many production lines to Vietnam and the Philippines. It wants to enter the Indian market also in a big way for outsourcing. India too is outsourcing many products from abroad.

China has been happy that Trump will scrap the biggest treaty of all, TPP (Trans Pacific Partnership) agreement which engulfs US and 11 countries in the Pacific and East Asia. It would not have made much difference to the trade liberalisation of the region per se because the US already has FTAs with all 11 members. But it would have led to job losses all around, according to a paper by noted Malaysian economist Jomo Kwami Sunderam. This was to be the mega treaty of this century and it was to be a treaty that would benefit the corporations and not the workers. According to one macroeconomic model, if implemented, the treaty would have cost loss of around 800,000 jobs over a decade and almost half a million jobs in the US alone. TPP is more about regulatory behaviour by the big corporations imposed on the partners’ firms. Many have opposed it in the past, except for Barak Obama who championed it. The TPP would have led to the rise of essential pharmaceutical drug prices manifold.

The TPP ( and the TTIP) according to some other economists requires more stringent enforcement requirements of intellectual property rights, reducing exemptions (like allowing compulsory licensing only in the case of emergencies), preventing parallel imports, extending exclusive rights to test data, making IPR provisions more detailed and prescriptive. Under the Treaty, Patent linkages would make it more difficult for many generic drugs to enter markets. This would make even life- saving drugs more expensive and would strengthen the pharmaceutical monopolies on cancer, heart disease and HIV/AIDS drugs.

If it went through, it would have increased the power of corporations relative to states and could prevent states from engaging in countercyclical measures to boost domestic demand. Macroeconomic stimulus packages that focus on boosting production would be prohibited by such an agreement. It would allow and enable corporations to litigate against governments that are perceived to be flouting these provisions because of their own policy goals. China may well assume the leadership of TPP if invited to do so in a new form in the face of US backing out.

There is also another important regional agreement: the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) which will enhance regional trade instead. It is a mega regional Free Trade Agreement between 16 Asia-Pacific countries, including India, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and 10 members of the ASEAN bloc. It may be able to create the largest regional trading bloc in the world. It aims to cover trade in goods and services, investment, competition and intellectual property. It aims at countering protectionism. It accounts for 3.4 billion people with a total GDP of $ 17 trillion approximately 40 per cent of the world’s trade. It has China and India as members. Already China is an important participant in industrial and infrastructural production in the ASEAN and South Asian region. Now it will forge ahead with its huge investment kitty of $4 trillion to $8 trillion under OBOR over an unspecified time horizon.

Members of the RCEP, including India, are worried that China may dump its excess capacity in many goods including steel as well as other highly subsidized items on the partners thereby harming the local industry and distorting trade in the process. The negotiation process begun three years ago is unlikely to be concluded in 2017.India is seeking greater market access in services as it is a leading services supplier. India with many competing industries is defensive about eliminating all tariffs and opening up goods trade especially to China.

Read Also | < style="color: #960f0f">What Obama has wrought

It is not just trade which is growing slowly and causing unemployment, but the advances in technology are causing job losses. Western businesses are pushing towards automation, digitalisation, robotics and 3 D printing that will undermine low wage countries’ biggest comparative advantage. It is responsible for the return of jobs in America. In state of the art plants, a bicycle can be produced with just 12 employees per shift. The same operation in China would need 60 people. Thus automation is helping jobs return to countries which developed the technology viz. the advanced countries. But Reshoring is bad news for developing countries that transformed themselves for export led manufactured growth. Now they may be seeing a reversal. Training workers in high tech manufacturing may be the order of the day in the future. For that to happen, there has to be a big push towards higher education and technical training which is lacking in many developing countries including in India.

The growth of regionalism and increase in regional trade is a clear possibility with India and China playing a pivotal role in increasing trade and investment in the ASEAN and South Asian region. China already has huge investments in Africa and Latin America. It can even help US in selling goods in China and other parts of the world.

China’s Alibaba, one of the biggest internet companies, is now offering an olive branch to Donald Trump in the face of a tariff hike which will upset Chinese business. Jack Ma, the chairman of Alibaba, has offered to sell small and medium US companies’ products on its portal for Chinese consumers. There will indeed be a big demand for American dairy and fruits as the Chinese have been suffering from problems of adulterated and poor quality food. There could be many other American goods which Jack Ma can sell and which will create jobs in America. High tariffs with a hike of 25 per cent imposed on Chinese goods on the other hand will most likely lead to retaliation.

India is somehow blessed by its huge size and resources which means a big domestic market and a growing prosperous middle class. Globalisation has increased growth no doubt and added variety to most Indians’ everyday life and consumption pattern, but there are many who have not been votaries of globalisation like the Bombay Club in the past. But now most industrialists concede that globalisation has enhanced competitiveness and have led to the improvement in the quality of their products. India is also undertaking foreign investments in other countries. Outgoing FDI is important for many Indian companies. Many Indians have found jobs abroad and NRI remittances are significant and highest in the south Asian region. Yet it is universally accepted that globalisation has led to sharp inequalities in incomes and the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer in India also.

According to a report by South Africa based New World Wealth, India is the second most unequal country globally with millionaires controlling 54 per cent of its wealth. With a total individual wealth of $5600 billion, it is among the 10 richest countries in the world. According to another source, Credit Suisse, the richest 5 per cent own 68.6 percent while the top 10 percent have 76.3 percent. Also the data shows that the richest 1 percent owned 36.8 percent of the country’s wealth in 2000 while the share of the top 10 percent was 65.9 per cent but by 2015 the top 1 percent owned more than 50 per cent.

To reduce inequality, the cushioning safety net to protect the poor and the vulnerable has to be strengthened though there are multiple social security schemes for the poor. Plugging leakages will reduce the number of poor and will make them shift to the middle classes. Public investment has to rise in healthcare and education as well as on infrastructure. This is all the more needed because private investment has been falling in recent years. There is need to implement reforms that are inclusive of the poor. There has to be progressive taxation and more people in the tax net which can bring more revenue to have public works and a more egalitarian society. If poverty is reduced drastically, the demand factor as a result of such a huge economy will help the regeneration of global trade in goods and services in the future.

Since attracting FDI seems to be a focal point, it can be targeted to industries that are labour intensive. This may lead to job creation for the unskilled. Otherwise, with nearly 1 million people joining the labour force every month, only service trade and the informal sector will be the available option for them.

India’s manufacturing sector is small (16 percent of the GDP) as compared to China and it has been the aim of the government to increase it to 25 per cent of the GDP. Only more jobs in the manufacturing sector can solve the problem and higher productivity will lead to an increase in its share.

India accounts for only two percent of the global trade. India’s exports can grow if the direction of trade changes. India can look towards Africa, South Asia and Latin America as export destinations because as long as the world remains full of poor people, there will always be demand for labour intensive cheap consumer goods, electronics, chemicals, machinery and pharmaceuticals-- India can fill the gap which China is likely to vacate.

Failure to create more jobs in highly populated countries may force labour to migrate to developed countries in a big way. Such migration may create more tensions in Europe and lead to the rise of right wing parties and their coming to power. Even if Trump succeeds in reshoring jobs back to the US especially from Mexico, it will not be easy to resist an increased flow of Mexican immigrants into US.

On the whole globalisation is likely to continue in a different and perhaps more beneficial form. China and India can play important roles even as US wishes to behave more protectionist and retreats behind tariffs and walls and move towards the Asian century.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

David Rusnok Researcher Strengthening National Climate Policy Implementation (SNAPFI) project DIW Germany

Read More +