-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The world community cannot hope to get a grip on this situation without finding a way of putting a price on carbon.

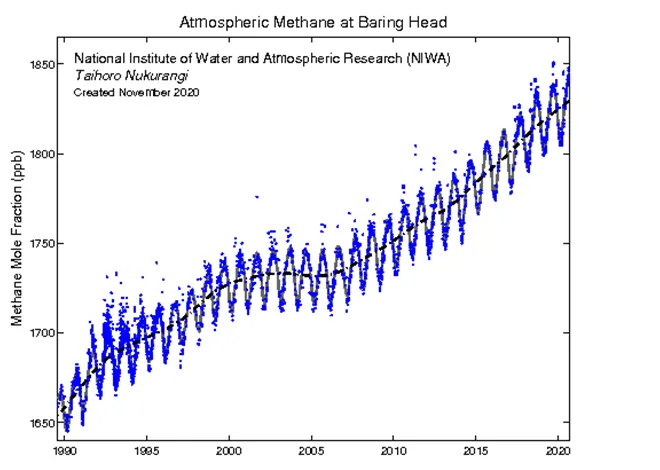

Climate change is the biggest threat that humanity has ever faced. Warming of the troposphere as a result of releasing man-made greenhouse gases into the atmosphere was predicted as long ago as 1896. Levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere have been measured continuously since 1958 at the Mauna Lao Observatory in Hawaii. CO2 has risen from a pre-industrial level of 280 parts per million (ppm) to 415 ppm (2021). Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas and has risen from a pre-industrial level of 722 parts per billion to 1,866 (2019). Methane levels plateaued in the ’90s, but have started rising again since 2008 as shown by the observatory at Baring Head in New Zealand.

Methane Graph courtesy of Dr Hinrich Schaefer, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), Wellington, New Zealand.

Methane Graph courtesy of Dr Hinrich Schaefer, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), Wellington, New Zealand.This has alarmed scientists who are, as yet, unsure as to the cause(s). Studies by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) favour a fossil fuel origin, and it is certainly true that the rise coincides with increased gas extraction globally, notably fracking. Other authorities favour tropical wetlands, but it is difficult to separate this from agricultural sources such as rice production in paddy fields, or methane released by ruminants such as sheep, cattle and goats. The latest data presented by Hinrich Schaefer at the first Mayday C4 Conference in London (May 1-3, 2021) indicates that agriculture is contributing significantly to these methane increases. Lurking in the background is the certainty that large quantities of methane will be released from thawing permafrost as temperatures in the Arctic continue to increase. An even more catastrophic scenario is the release of methane from the Arctic seabed where roughly 500 billion tonnes is stored in the form of clathrates. In 2013, Peter Wadhams and his colleagues from Cambridge University predicted that the release of just 50 billion tonnes from the East Siberian Ice Shelf would raise global temperatures by 0.6 degrees Centigrade (C). In October 2020, scientists reported significant methane releases from this precise area of the Arctic Ocean where the continental shelf is only 30 metres below the surface. Scientists are unsure whether this is a new phenomenon or whether they are observing something that has been happening for many years; other observers regard this event as signalling the start of irreversible climate change.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) does not include release of methane from the Arctic seabed in their climate projections, as they regard it as a “high impact, low probability event.” This approach may need to be revisited.

In the late ’70s, the US Government asked the Jason Committee to advise on global warming. The committee concluded that a doubling of CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere would lead to a rise of temperature to 2–3 degrees Centigrade. However, the committee did not make policy recommendations, and there is considerable dispute as to why nothing more was done at that time.

Global temperatures are monitored and measured by a number of different organisations and these have generated a number of data sets that are in remarkable agreement. The latest findings show that temperature increases are not evenly distributed across the surface of the planet. Air heats up quicker than water, so air temperatures over land are rising quicker than sea surface temperatures. Because most of the Earth’s land mass is located in the Northern hemisphere, temperatures in the North are higher than the South. The greatest temperature changes are being witnessed at the poles as the melting of sea-ice allows greater heat absorption by the oceans. Thus, whilst the average global temperature has increased since 1850 by only 1.2°C worldwide, over Europe the increase is 2°C, and in the Arctic, it is more than 3°C since 1900.

Other phenomena not previously witnessed are afflicting the Arctic region including progressive thinning of the sea-ice, record-breaking loss of sea-ice during the summer, temperature fluctuations up to 30°C above the seasonal average, and wildfires within the Arctic Circle. These not only release carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, they also darken the snow leading to loss of albedo, and further heat absorption.

Another IPCC prediction that is proving to be overly cautious is melting of the ice-caps; four trillion tonnes of ice has been lost from Greenland since 1990, and a trillion tonnes in the past four years. Currently, ice is melting at 8,500 metric tonnes per second, a rate of loss that was not supposed to occur until 2040 according to the IPCC. Much of the sea-level rise (SLR) that has occurred thus far is due to thermal expansion of the oceans, but it is apparent that ice-cap melting will contribute an increasing percentage of SLR. The following is an original graph showing data from 1750 to the present day prepared by Professor Philip Woodworth at the National Oceanography Centre in Liverpool.

Source: The National Oceanography centre in Liverpool

Source: The National Oceanography centre in LiverpoolIt is significant that the mean SLR since 1900 is 1.7 millimetres per annum (mmpa), but since 1993, this has increased to 3.2 mmpa. This process can only end badly for coastal cities and low-lying areas such as Bangladesh, Vietnam, and the Nile delta, not to mention Pacific islands whose average height above sea level is less than 2 metres. It should be recognised that sea levels do not need to flood communities before towns or cities are abandoned. Storm surges and increasingly frequent or ferocious hurricanes will persuade communities to move long before the sea actually reaches their front door, as Storms Katrina and Sandy demonstrated in New Orleans and New York.

Approximately 10 percent of the world’s population live in coastal communities that are less than 10 metres above sea level, so the number of displaced persons could approach 1 billion.

This year the UK Government will host the 26th Climate Change Conference, known as COP26, in Glasgow from 1-12 November inclusive. The President is Alok Sharma, Secretary of State at BEIS, but there is also a COP26 Cabinet Committee chaired by the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, whose stated purpose is to “oversee arrangements for COP 26.” This division of responsibility could cause problems if areas of responsibility are not clearly demarcated.

Another organisation which without a clearly defined hierarchical structure is Extinction Rebellion (XR), which exploded onto the scene in 2018 with a series of eye-catching demonstrations in Central London and elsewhere. At the same time, Greta Thunberg started a protest outside of her school in Sweden. These two events achieved in one year what 30 years of lobbying and hundreds of other environmental groups had conspicuously failed to do, which was to move global warming up the political agenda.

XR has been wrongly accused of being a terrorist organisation. In reality, it is a global movement that believes in and practices non-violent direct action and civil disobedience, an approach that has was advocated by leaders such as Nelson Mandela, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, luminaries of civil rights movements whom one imagines, even the current Home Secretary does not regard as terrorists.

XR have been frustrated by the COVID-19 pandemic, but it has also allowed time for reflection as to what tactics will be most effective in the run-up to COP26. The incident at Channing town underground station in 2019, where a protestor was dragged from the roof of a tube train, has served as a wake-up call for XR, and a recognition that disruptive tactics that prevent people from getting back to work, or even putting their lives back in order post-COVID could backfire badly.

The potential for repeated confrontations between XR demonstrators and the forces of law and order are obvious, and would defeat the purpose of XR’s primary purpose: To find a solution to global warming and to prevent climate breakdown and societal collapse. The best way of achieving those goals is to make COP26 a resounding success because, until now, every COP event has been a failure. We need COP26 to be different if we are to have any chance of saving ourselves and most other species from extinction.

The graph below shows greenhouse gas emissions over a 40-year period, from 1970–2010. In 1990, the base-line year for Kyoto, GHG emissions totalled 38 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) world-wide. By 2010, this had risen to 49 billion CO2e of which only 65 percent (31.6 billion tonnes) was due to CO2 emissions from energy production and other industrial activities such as cement manufacture. CO2 emissions from agriculture, forestry, and other land use (AFOLU) accounted for another 11 percent. Other greenhouse gases such as methane (16 percent), nitrous oxide (6 percent) and trace gases such as halocarbons (2 percent) represented the remaining 24 percent. In 2019, industrial emissions of CO2 peaked at 36.6 billion tonnes, which indicates that total GHGs were slightly over 56 billion tonnes of CO2e, a figure that is seldom discussed by politicians or the media as they are not published on an annual basis.

Industrial emissions of CO2 in 2020 have fallen by 2.4 billion tonnes due to the COVID pandemic but that is only equivalent to a reduction of 7 percent. In order to limit global warming to the preferred limit of 1.5℃ agreed in Paris in 2015, the IPCC estimate that reductions of 7.7 percent are required every year over the coming decade. The only government to recognise this requirement is the Scottish government that has announced its intention of reducing carbon emissions by 75 percent by 2030 compared with 1990. Joe Biden has offered only 50 percent by 2030, and that is from a 2005 base-line, making the target easier to achieve.

There are two further concerns that are worrying the scientific community. Firstly, due to the thermal inertia of the oceans, we are already well beyond the 1.5℃ limit because there is another 0.6℃ of "committed warming" built into the atmosphere if GHG levels stay at their present level. Recent modelling demonstrates that if all GHG emissions stop tomorrow (a rather preposterous scenario) OR if we found an energy efficient way to capture carbon directly from the atmosphere, then it might be possible to keep temperature rises below 1.5℃.

The other major concern is that temperatures are rising more rapidly than predicted. A paper published in Nature in 2018, predicted that we will reach 1.5 degrees of warming by 2030, rather than the IPCC estimate of 2040.

Source: Nature

Source: NatureThe deviation from IPCC forecasts is partly due to rapidly rising methane and possibly a reduction in sulphur emissions from power stations and shipping. Lower sulphur emissions rapidly result in lower concentration of sulphate aerosols in the atmosphere, which normally exert a cooling effect. It is difficult to prove this as the Republican leader of the Ways and Means Committee refused funding for NASA in the 1990s to put sulphate monitoring equipment on their satellites.

However, temperatures have confounded even the authors of this paper. In 2020, we reached 1.2℃ of warming. The World Meteorological Organisation forecast in June 2021 that there was a 90 percent chance of breaching 1.5C of warming before 2026.

It is obvious that the Kyoto Protocol has proven a political failure. Annual CO2 emissions have risen by 60 percent since 1990, and more anthropogenic CO2 has been emitted since 1990 than in all the previous years going back to the start of the Indutrial Revolution. The world community cannot hope to get a grip on this situation without finding a way of putting a price on carbon; and this leads us to the next stage: The Global Carbon Incentive Fund. Meanwhile, we absolutely must do everything in our power to make COP26 a success, and that means every country in the world recognising the extreme urgency of the climate situation. As I wrote in a Lancet editorial published in April 1989: “The costs may be considerable, but the costs of doing nothing are incalculable”.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Robin Russell-Jones is the facilitator of the 2021 St Georges Climate Consultations at Windsor Castle. He is the Founder of Help Rescue the Planet (hrtp.co.uk) ...

Read More +