-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Months after Climate Minister Chris Bowen hailed Australia as “the green hydrogen capital of the world,” several projects have stalled, and many remain in doubt.

Image Source: Getty Images

One of the most promising pathways towards a clean energy future, green hydrogen (H₂) emerged as a pillar of decarbonisation, particularly for hard-to-abate industries like steelmaking and heavy transport. Green H₂ is produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using renewable electricity. Grey H₂, which is produced from fossil fuels such as natural gas, emits substantial amounts of greenhouse gases. Blue H₂ combines this method with carbon capture mechanisms to reduce emissions. Green H₂, on the other hand, results in zero emissions and has been projected to become a major global export in the future.

After a year of regulatory inconsistency and political uncertainty in the backdrop of a hard-fought election, the nascent green H₂ industry has faced a number of hurdles.

Australia was on track to become one of the leading producers and exporters of green H₂, with Australian green energy giant Fortescue having already put pen to paper on a deal to supply German energy company E.ON with the renewable energy source. Why then, has the industry suddenly stuttered?

After a year of regulatory inconsistency and political uncertainty in the backdrop of a hard-fought election, the nascent green H₂ industry has faced a number of hurdles. In recent months, a wave of cancellations, disinvestment, and scepticism has cast a pall over the sector.

Major projects have collapsed as several Australian state governments pulled financial backing due to ballooning costs and shifting priorities. The cornerstone CQ-H2 project was terminated after a critical US$1 billion funding request was rejected, following the Liberal National Party’s election victory in Queensland. In New South Wales, Origin Energy backed out of plans for establishing a ‘hydrogen hub’ in Hunter Valley. South Australia also saw the dismantling of the dedicated hydrogen office planned at Whyalla, with nearly 600 billion Australian dollars (A$) being redirected away from the sector.

Damaging rhetoric by sceptics in the opposition has further complicated the decarbonisation outlook in the country. In the run-up to the Australian elections in May, the conservative coalition slammed government spending on what has often been dubbed a “fantasy” in conservative discourse. In a nation scarred by high rates of inflation and rising energy prices, this sort of campaign talk resonated with a significant voter base. When green energy is politicised, made into a partisan issue, and vilified for rising costs, the unfortunate outcome is that it becomes more challenging to advocate for — and even more so to secure government funding.

Although Labour, which has previously championed Australia’s green hydrogen revolution, ultimately emerged victorious, the perception of clean energy has most certainly shifted. The green hydrogen ambition will remain a part of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s government’s Future Made in Australia policy; yet, work remains to be done. Addressing the transition, as well as Australia’s rising coal exports, with clarity will go some way in allaying fears. Backing clean energy projects with policy coherence and state finance can further help revive the sector.

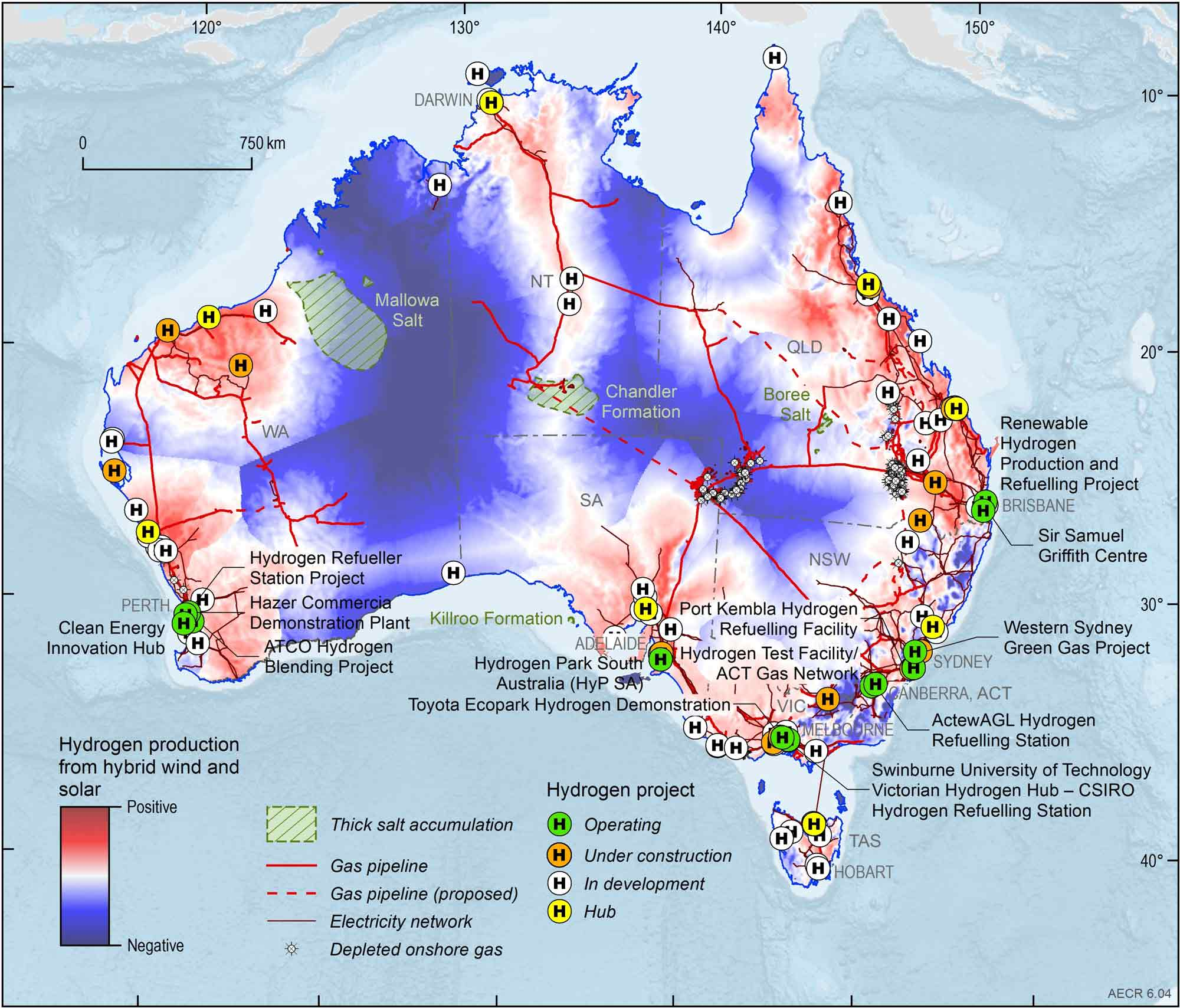

Locations and status of hydrogen projects and proposed hydrogen hubs in Australia. Salt caverns have high Green H₂ storage capacity. (March 2023)

Source: Australian Government | Geoscience Australia

Aside from the surging coal exports, the Albanese government has also been criticised for continuing to allow the expansion of Australian coal mines. Labour’s plan for a federal environment protection agency was also shelved by Albanese before the last election, fearing it could provoke backlash in Western Australia. However, there has been a recent breakthrough, as a New South Wales court blocked the state’s largest coal mine expansion. Experts say that the industry has entered something of a disillusionment phase, common with any new disruptive technology following the initial hype. While green hydrogen is not the catch-all solution it was touted to be, its role in hard-to-abate industries isn’t speculative. Green H₂ is already in action, and its use will inevitably continue as supply chain vulnerabilities and surging costs of grey steel become more pronounced.

Aside from the surging coal exports, the Albanese government has also been criticised for continuing to allow the expansion of Australian coal mines.

Australia and the rest of the world should not be deterred by the setbacks the industry has faced down under; such challenges are to be expected. When left entirely to market forces, the transition to clean energy is likely to be controversial in most countries and expensive in the short term. With robust policy support and adequate financing, costs will decline in the medium and long term as industry practices improve. Green hydrogen projects will not become more affordable until the initial hurdles are overcome with adequate state support. Governments have to step in to support clean energy in the interest of their own energy security.

What the rest of the world can learn from Australia’s experience is that the road to a green energy future is not always linear, and the effort is very likely to face setbacks. These are often compounded by shifting government priorities, insufficient policy backing, and fiscal uncertainty. A long-term vision that prioritises energy security through renewables rather than subsidising legacy fossil fuels for short-term political gain is the need of the hour. Following the US retreat from any meaningful climate action, Australia must realise it can play a pivotal role in decarbonising the Indo-Pacific. Fostering cooperation with Japan, where green H₂ is increasingly in demand, would be a welcome step. Indo-Australian collaboration in sustainable steelmaking projects can also be scaled up to strengthen Indo-Pacific climate cooperation.

Krishna Vohra is a Junior Fellow with the Centre for Economy and Growth at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Krishna Vohra is a Junior Fellow at the Centre for Economy and Growth. His primary research areas include energy, technology, and the geopolitics of climate ...

Read More +