-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The HAC advocates for a strong Plastics Treaty which would also bring developing countries like India under a similar binding timeline to end plastic pollution. This is a major obstacle in reaching a consensus.

Canada is all set to host the fourth session of negotiations to frame a legally binding multilateral instrument aimed at ending plastic pollution. This will be the last session for negotiators before November’s final session in Busan, South Korea, where the negotiations are currently mandated to end with a final negotiated treaty document. The session in Canada is scheduled for 23-29 April and is expected to remain a contestation between countries that are seeking a treaty that imposes a global target to end plastic pollution with a blanket application on all party nations on the one hand, and countries that have strongly resisted such negotiating options by proposing that national circumstances of every party must be accounted for before any targets are imposed on individual nations. Another major obstacle in reaching a consensus is finding a common approach towards ending plastic pollution.

India’s stance is akin to this downstream approach as our negotiators have clearly expressed that ‘plastic per se is not menace’, and it is unmanaged and littered waste that causes adverse impacts on the environment.

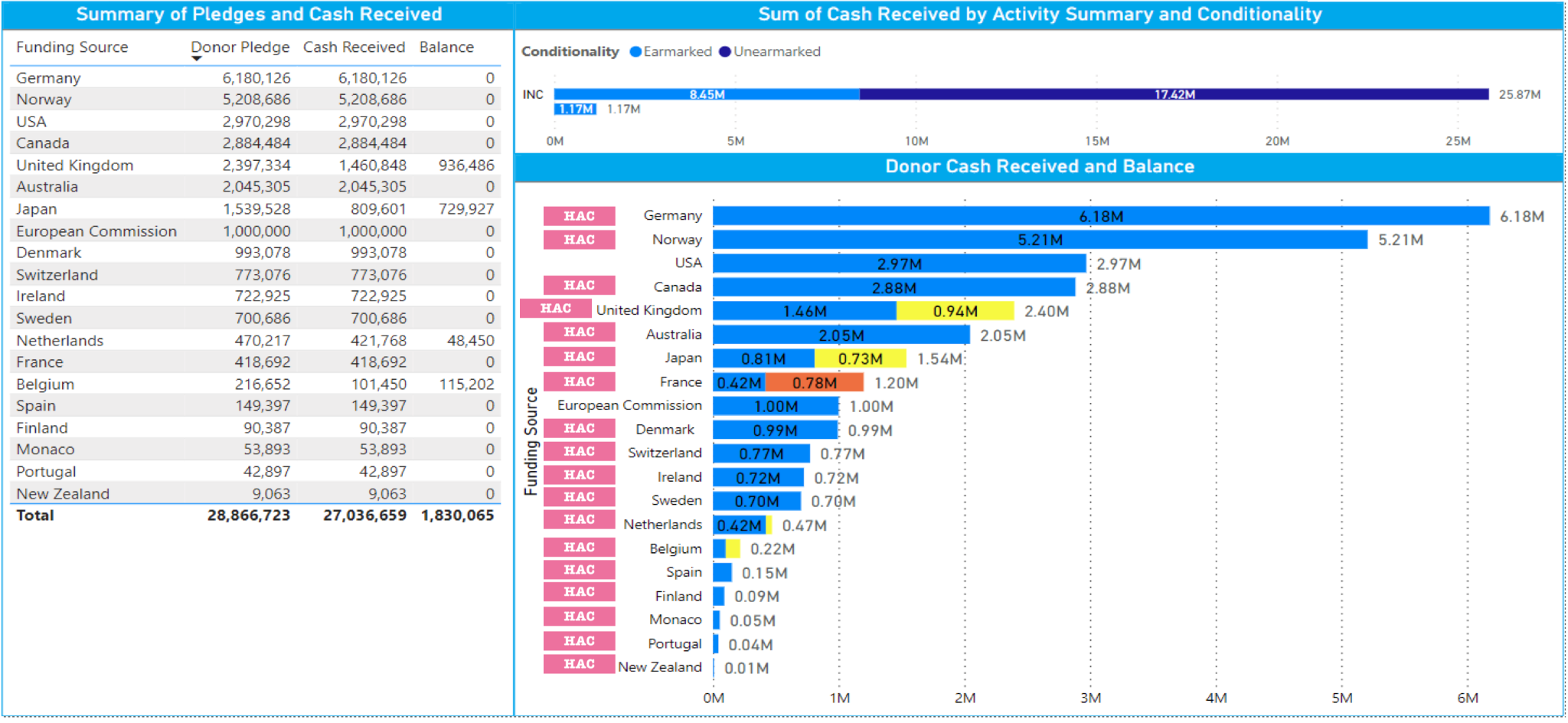

One approach taken by the Global Coalition for Plastics Sustainability, a group of like-minded states—Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Cuba, China and Bahrain—in the last negotiations that took place in Nairobi in November 2023, is based on a ‘downstream approach’ that identifies plastic pollution as a direct consequence of unscientific plastic waste disposal. India’s stance is akin to this downstream approach as our negotiators have clearly expressed that ‘plastic per se is not menace’, and it is unmanaged and littered waste that causes adverse impacts on the environment. It directly contends with the ‘upstream approach’ adopted by negotiators from the 64 nations that form the High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution (HAC) which is upstream-heavy since they aim to end plastic pollution by 2040, by not only focusing on waste disposal but also by putting a cap on the production capacities of plastic manufacturing nations. It must be highlighted that the nations driving the High Ambition Coalition are also the largest funders of the Secretariat hosting the negotiations on the Plastics Treaty (Figure 1), making the High Ambition Coalition member states key financial drivers of the treaty negotiations. Therefore, they also form the dominant narrative that is aimed at galvanising support for a strong and binding Plastics Treaty.

Figure 1: The Nations Funding the Negotiation Meetings and Conferences. (HAC member states are tagged)

Source: UNEP

The High Ambition Coalition has mobilised commendable traction to bring the issue of plasticsand marine pollution onto the multilateral high table, and is also supported by the Pacific Islands Forum which issued a communique to its 18 island member states to join the Coalition while negotiating the Plastics Treaty in UNEP. Yet, the policy stance adopted by High Ambition Coalition states has been opposed by India and those in the Global Coalition for Plastics Sustainability. It has led to some commentators labelling India as favouring the petrochemical industry over environmental concerns, primarily because petrochemicals provide the feedstock for plastics manufacturing and are estimated to save the oil and gas sector growth in the face of a decline in the demand due to adoption of cleaner fuel alternatives. Since the treaty negotiations are also aimed at curbing the production of plastics, they conflict with the expansion of the Indian petrochemical industry. Although these concerns around India remain valid, they remain focused on a propagation of the narrative used by the High Ambition Coalition states, which at the end of the day is one side of the negotiation in a broader collaborative multilateral effort. The logic behind the stance adopted by Indian negotiators is not of a collusion with the petrochemical lobby, but of facilitating multilateral collaboration with High Ambition Coalition states on terms which do not ignore the difference between the developmental levels of key High Ambition Coalition states like Norway, Germany, UK, Canada, Japan and those of India.

The policy stance adopted by High Ambition Coalition states has been opposed by India and those in the Global Coalition for Plastics Sustainability.

The most glaring red line drawn by India during these negotiations is that the treaty must retain a differentiation between the developed and developing countries. Consequently, Indian negotiators have repeatedly proposed the inclusion of the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) into the treaty. It has been supported by similar voices from Brazil, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, Panama, Gabon, Senegal, and Tunisia, among others. On the contrary, most High Ambition Coalition nations want a stronger treaty that does not dilute the aim of ending plastic pollution. High Ambition Coalition states like New Zealand and the EU are also of the view that raw materials for plastic production must also be brought under regulation via the treaty, something India does not completely concur. These negotiations also bear an uncanny resemblance to the climate negotiations where the principle of CBDR was only introduced because the United States (US) managed to get it through the adamant Western nations which wanted a strong climate agreement that equally binds all, irrespective of developmental differences. The same set of Western nations now form the HAC and advocate for a strong treaty that means that developing countries like India must also be brought under a similar binding timeline to end plastic pollution, similar to the one set for the developed countries, i.e., 2040. Even a glance at the per capita GDP of High Ambition Coalition states (Figure 2) tells us that they do not hold the overriding priorities of development that India holds.

Figure 2: Per Capita GDP (in US $) of key HAC member states (right) comparative to the states negotiating for CBDR (left)

Source: World Bank

Another point of contention for Indian negotiators has been regarding the Rules of Procedure as HAC states like Norway, the UK, Switzerland and the EU countries wanted the negotiation decisions to be taken by a two-third majority voting. It is widely believed that the HAC strategically pushed for this two-third voting criterion as they were well aware that it would be difficult to garner consensus on a treaty that binds all parties on an equal footing, irrespective of the inter-party developmental gaps. On the contrary, India wanted the principle of consensus to be the bedrock of adopting decisions as it reflects the essence of multilateral collaboration where all voices have a say in adopting decisions. Owing to India’s push, treaty negotiations now operate on provisional rules of procedure under which all decisions on matters of substance are to be agreed by consensus. It is crucial for non-Western developing states like India as it allows for the agreement of all parties before any binding treaty design is finalised.

Owing to India’s push, treaty negotiations now operate on provisional rules of procedure under which all decisions on matters of substance are to be agreed by consensus.

The friction between HAC members and those of the Global Coalition for Plastics Sustainability is bound to play a crucial role in moulding the final structure of the Plastics Treaty. It would be better to model the treaty on the lines of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) which divides countries into various categories and puts them into different Annexes. Though the HAC states are justified in trying for a ‘strong’ treaty that binds all and regulates all, they must come to terms that to achieve a multilateral instrument ready by the end of 2024 all parties must arrive at consensus in the negotiations. Alhough the developed Western nations of the High Ambition Coalition may not see the Paris Agreement as the best prototype to be followed while advocating for a Plastics Treaty, they must not ignore the accommodative capacity of the agreement that got the developing nations on board with the developed. It must also be acknowledged that players like India are not opposed to the treaty but seek recognition of their national circumstances. This nature of India’s call for including CBDR in the Plastics Treaty is intrinsically collaborative as it calls for accommodation so that the less developed countries can be onboard and curb pollution from plastic as they themselves suffer from its negative effects. The broader negotiations must also account for the possibility of a Trump administration in the US and should design the treaty to be reasonably safe from a US pull-out. The upcoming negotiations in Canada will provide enough clarity on whether negotiators gravitate towards finding common ground or allow ambition to stymie accommodation and collaboration.

Angad Singh Brar is a Research Assistant at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Angad Singh Brar was a Research Assistant at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. His research focuses on issues of global governance, multilateralism, India’s engagement of ...

Read More +