-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

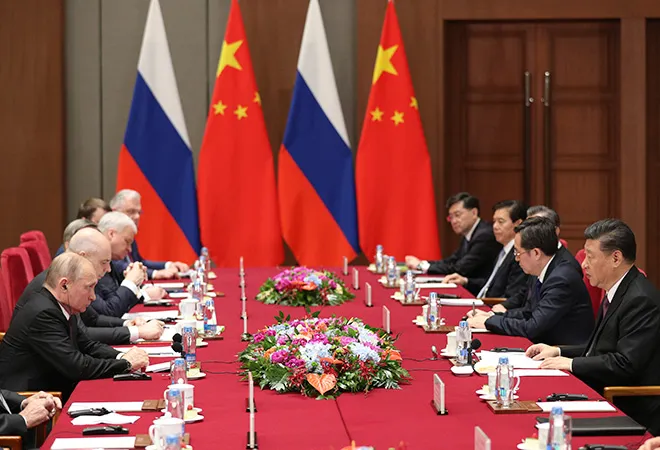

The great power rivalry between the US, Russia and China has an interesting history, Beijing being highly volatile of the trio by frequently changing camps. During the Cold War, Soviet Union and China initially opposed the capitalist West before China ganged up with the US to balance their common enemy, USSR in early 1970s. China again seems to be with Russia due to current American aggression against them, but, Central Asia is a common area of interest and a sensitive spot for both. Due to security reasons, Russia treats the region as its sphere of influence while for China, Central Asia is critical for its trade, energy and security of its Uighur-dominated secession prone Xinjiang Province. Under its March West policy, China is moving into Eurasia to break out of its encirclement by the US and its allies in the eastern front. China, which was portrayed as an enemy of Islam by the Soviets in Central Asia during the Cold War has now made massive inroads in the region. Russia dominates security, cultural and historical memory of Central Asia while China’s massive economy allows Beijing to build leverage in the region, especially through its Belt and Road initiative (BRI). The Russia-China cooperation in Central Asia started mainly in 2001, when Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) was established by Beijing. In the same year, the US and NATO military intervention in Afghanistan brought fears of encirclement for both, Russia and China and set the stage for their regional cooperation in Central Asia. However, for Russia, the reality has been to manage China’s rise in its backyard, ceding its traditional influence in the region in some areas like trade and energy. Now, that the US President Donald Trump is desperate to pullout his troops from Afghanistan, there are chances that Russia and China’s competition for Central Asia may heat up. Such signs are already visible in the regional geopolitics.

BRI has caused certain concerns in Moscow, and Russia did not miss the point that China announced launch of BRI in Kazakhstan in 2013, not in Russia. In 2018, China became biggest trade partner of three Central Asian countries – Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Financially, the Russians cannot compete with the Chinese, who have very deep pockets. America, under President Donald Trump has shown no interest in Central Asia leaving the region almost free for Chinese penetration. Russia, however, won’t throw in the towel yet. President Vladimir Putin came up with post-Soviet economic integration initiative, the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). It is not a coincidence that when the US started to withdraw its troops from Afghanistan in 2014, both China and Russia announced their respective initiatives (BRI in 2013, EEU in 2015). The security matters in the region are overseen by Russia led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) where China is not a member. In the trilateral great power dynamics of Russia, the US and China, EEU is often seen as a Russian attempt to geopolitically reintegrate the post-Soviet countries in order to maintain Russia’s relevance in times of US-China’s fight for supremacy. However, the idea has not generated the expected results and the BRI challenges framework of EEU. Possibly, that is why; Russia and China agreed to link their initiatives in 2015 to avert hiccups in their overall relationship, but problems persist.

The EEU is a regional organization with a regulatory and legal framework as well as membership criteria. The BRI, on the other hand, has a light institutional architecture and remains an amorphous idea. China has been leaning toward bilateral negotiations with EEU nations over BRI, to Russia's disadvantage. Russia, on the other hand, prefers China should adopt multilateral approach for SREB through groupings like EEU and SCO where it has a better chance to safeguard its interests by shaping China’s dealings with former Soviet republics. In this context, Russia has also proposed ‘Greater Eurasian Partnership’ focusing on multilateral cooperation between regional initiatives like EEU, SCO, CIS, ASEAN and countries like Iran, Turkey, India, Japan and South Korea to dilute China’s hegemonic ambitions in Eurasia. Another difference between EEU and BRI is that with its high external tariffs, the EEU is designed to stimulate internal trade. It does not have the outward-looking focus of the BRI. Concerned about China’s manufacturing prowess and huge economy, Russia and the Central Asian countries have long resisted Beijing's attempts to create a SCO free trade area and SCO Development Bank. Russia may be struggling to keep its flock together but recently, Uzbekistan has hinted it may join EEU as 70 percent of its trade is with EEU members and once the grouping adopts common product making standards, Uzbek exports would face problems in entering EEU market.

There is no clarity on how the two Eurasian giants would reconcile their problem of transportation in the region. China's standard rail gauge is 1435 mm against Russia's 1520 mm. Railway is a strategic asset as it can also be used for troop mobilization apart from trade and Moscow has not been too enthusiastic about initiatives like China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway. Some quarters in Russian policy circles also fear that the BRI would become the main land transit route between Asia and Europe at the expense of Russia's Trans-Siberian railway, in which Moscow plans to infuse billions of dollars to reinvigorate it. But given Moscow’s economic woes, it may find difficult to do so. In order to have some leverage over China, Russia wants to ensure that the planned rail link connecting China and Europe should pass through its territory, instead of circumventing it via Central Asia only. However, Russia’s troubled relations with European Union could cast a shadow over such ambitions prompting China to bypass Russia. China, of late, is breaking out of Russia's shadow and stepping up its security presence in the region. China inked an anti-terror alliance with Pakistan, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, excluding Russia in 2016. Moscow had made an attempt at a similar agreement with the three countries in the past, and there were several meetings between the nation's leaders from 2009 to 2012, but nothing materialized. China’s debt-diplomacy may also be a concern for Russia. Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan owe almost half of their public debt to China. With limited means to repay this debt, the strategic assets of both the Central Asian countries are vulnerable to China’s control. Of late, Western media has highlighted presence of a Chinese military base in Tajikistan setting off speculation that Beijing may have pulled off a ‘Hambantota’ sort of deal with Tajikistan. It is in this context that constant media reports about Russia’s plan to have a second military base in Kyrgyzstan has become important. Russia has been overplaying the threat of Islamic State in Afghanistan to further strengthen its military presence in Central Asia. Make no mistake; it has a Chinese angle to it

Russia’s problems with Europe and NATO have kept Moscow’s focus on its western flank allowing China to sneak into post-Soviet space. Russia is very sensitive to its great power tradition but problems with the West have deepened its rapprochement with Beijing. However, big powers like Russia are unlikely to quietly bandwagon with another power and in its dealings with China; Russia shows signs of tactical bandwagoning where there are areas of disagreement, Central Asia being one of them. This is akin to multi-polarity at global level with areas of influence at regional level. Russia has tried to build a European identity and to an extent, has followed European model as it talks of diversity, plurality and no universal model of development. Driven by the Middle Kingdom mentality, China, on the other hand, poses an alternative to Europe without following its model of development and is also technologically advanced. In this sense, Russia and China are different and in the long run, may not come together against the West. As China's power grows in Central Asia, this could well become the area where latent differences between Russia and China become prominent in times to come, especially as the US loses interest in the region. The development, of course, would be welcomed in New Delhi.

Dr Raj Kumar Sharma is a Consultant, Faculty of Political Science, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr Raj Kumar Sharma is a Visiting Fellow at United Service Institution of India New Delhi. Prior to it he was Maharishi Kanad Post-Doc Fellow ...

Read More +