-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The Centre must proceed with caution as ill–timed and hasty measures can damage the efforts of integration.

The revocation of Article 370 has polarised the global community on issues pertaining to its legal basis and humanitarian implications. More specifically, the lockdown imposed in the Valley and its effects on civilian life is especially worrisome. However, in the discourse — both positive and negative — surrounding the decision, the effect of violence and protests on the cultural loci of Kashmir has been relatively undeserved. Monuments, mosques, galleries and other such cultural centres are an important source of Kashmiri identity that must be preserved. Moreover, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi reportedly keen on reopening 50,000 temples in the Kashmir Valley, an examination of the relevance of the region’s cultural capital and its role in forging a coherent civilian identity is imperative. In light of the growing alienation of the civilian population in Kashmir, the decision to reopen temples must account for the potential dilution in cultural spaces that embody a Kashmiri identity and its potential to further alienate the people India hopes to integrate.

In light of the growing alienation of the civilian population in Kashmir, the decision to reopen temples must account for the potential dilution in cultural spaces that embody a Kashmiri identity and its potential to further alienate the people India hopes to integrate.

Even as the history of the Second World War is vividly etched in public memory, the effect of the violence on the art and cultural centres of the Allied powers evades recollection. According to some reports, the Nazis transferred over five million cultural objects to the Third Reich. More recently, in the protracted conflict taking place in the Middle East, the fate of cultural and religious symbols has been grim. Assad’s Syrian regime and their onslaught on rebel forces in Syria has led to the destruction of numerous archeological sites including the famous historical site of Apello. While during the Islamist expansion in Mali, shrines catering to the Sufi beliefs of citizens was destroyed as it confronted the Islamic inclinations of the occupying forces. The 6th century monumental statues of the Buddhas of Bamyan were similarly destroyed by the Taliban in their pursuit of religious iconoclasm. Thus, either through the doings of the armed forces or the rebelling insurgents, centres of art and culture invariably bear the brunt of the conflict. The aforementioned cases depicting the unfortunate state of art and culture in conflict zones has persisted at a time when legal instruments like the Hague Convention of 1954 and the World Heritage Convention of 1972 has been instituted to protect such interests. Reasons for the grim state of structures embodying the cultural capital of a conflict zone could be twofold. The rationale that monuments, shrines and other such structures would be compromised as a likely consequence of overt war seems plausible but far too simplistic. In some of the aforementioned cases, it was a strategic objective of the occupying force to destroy remnants of culture left in the land. Thus, simply seeing such occurrences as the product of collateral damage due to bombings or violent retaliations is not enough. Often, like in the case of the Islamist occupation in Mali, a systematic ploy to destroy the adversary’s cultural roots exists. It is this troubling pattern observed in certain contexts of conflict that reinstate the importance of preserving centres of religion and culture in the land affected by protracted war so as to help safeguard the cultural identity of the oppressed.

Even prior to the contested revocation of Article 370, the effects of a protracted conflict between two warring nation states on an increasingly aggrieved civilian population has been extensive. A relatively underexplored implication of the conflict pertains to the gradual erosion of Kashmiri cultural history. If one takes stock of how this erosion has taken place, government negligence, Kashmir’s vulnerability to natural disasters and military presence in the Valley has been implicated as key factors. For instance, a shrine built in 1438 in Budgam, around the grave of Sufi poet, Sheikh Noor Din met with an unfortunate end. In the summer of 1995, the conflict in the Valley had escalated and a total of 21 militants used this shrine as a hideout. To kill the militants and succeed in their counterterrorism operation, security forces used gunpowder to set the shrine ablaze. The case of this shrine is one of many such cases wherein cultural centers in Kashmir have been adversely affected by the presence of a conflict. Whether the actions of the security forces was justified or not is a contentious issue. Some may argue that sacrificing the shrine was necessary to fulfil the larger goal of fighting the militancy while others engaging in counterfactuals may believe that forces could have found less damaging alternatives. Irrespective of where one stands on accepting the destruction of heritage and cultural sites as an inevitable consequence of war, its importance in forging in–group identity must not be trivialised. These sentiments were echoed in the UN General Assembly resolution of 2015 that stated, “The destruction of cultural heritage erases the collective memories of a nation, destabilises communities and threatens their cultural identity”.

A relatively underexplored implication of the conflict pertains to the gradual erosion of Kashmiri cultural history. If one takes stock of how this erosion has taken place, government negligence, Kashmir’s vulnerability to natural disasters and military presence in the Valley has been implicated as key factors.

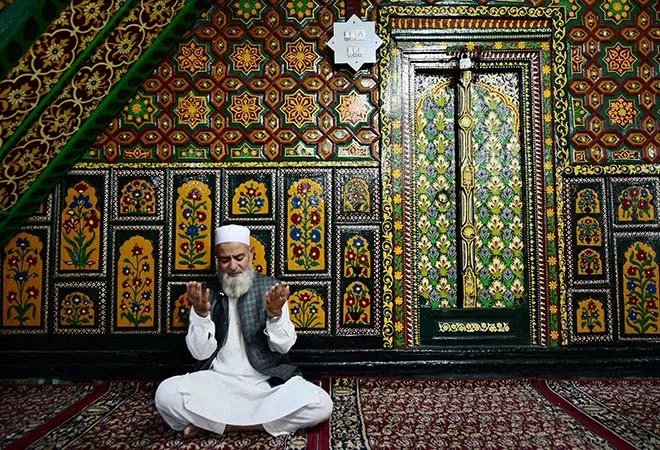

The situation in the Valley is tense and uncertain. In these times, the remnants of culture become especially important in bringing communities together and facilitating social relations. For instance, many Kashmiris have spoken about the importance of local mosques as a means to bring the community together during the lockdown. During the extended curfew post the revocation of Article 370, the local mosque became a storehouse for excess food and other essential supplies. Thus, a religious structure, in the context of a curfew, comes to serve many functions for community building that may not be intuitively associated with its core functionality. Moreover, such mosques, museums and shrines cumulatively help build a sense of pride and belongingness between the local civilian population and the land of Kashmir. It is this aforementioned association that the Centre must internalise as it hopes to integrate the Valley into the ethos of India.

In light of these insights, Prime Minister Modi’s decision to conduct a survey of missing temples, schools and theatres in the Valley in order to inform future course of action for rebuilding purposes must be done with caution. The centre’s decision is certainly laudable as the survey may be a step towards the goal of restoring Kashmiriyat, the Valley’s glorious symbiotic culture of communal and social harmony. However, a dilution in the cultural capital that aligns with the present civilian population in Kashmir as a result of the reopening of temples may not help in the larger goal of integration. Symbols of in–group identity are an essential cog in creating a homogenised cultural identity, which, if threatened, could further alienate a group we hope to call “ours”.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Prithvi Iyer was a Research Assistant at Observer Research Foundation Mumbai. His research interests include understanding the mental health implications of political conflict the role ...

Read More +