The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (

GBF) that emerged from the Conference of Parties (COP15) in December 2022 places the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities (

IPLCs) as ‘custodians of biodiversity and partners in the conservation, restoration and sustainable use.’ In doing so, it builds upon the considerations for the implementation of

Aichi Biodiversity Targets, which were adopted at COP10 in Japan in October 2010.

A review of the progress made under the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 indicates that

not even one out of the 20 Aichi targets has been achieved completely, thus there is a need to review and facilitate discussions on the existing laws and policies and delve into the reasons behind the failure of on-ground implementation.

ICCAs

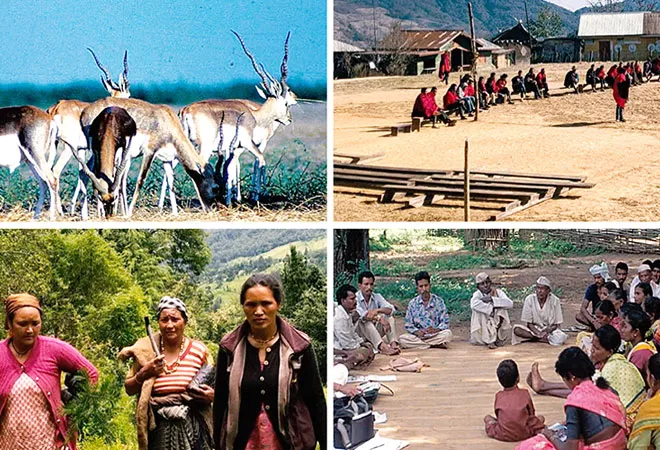

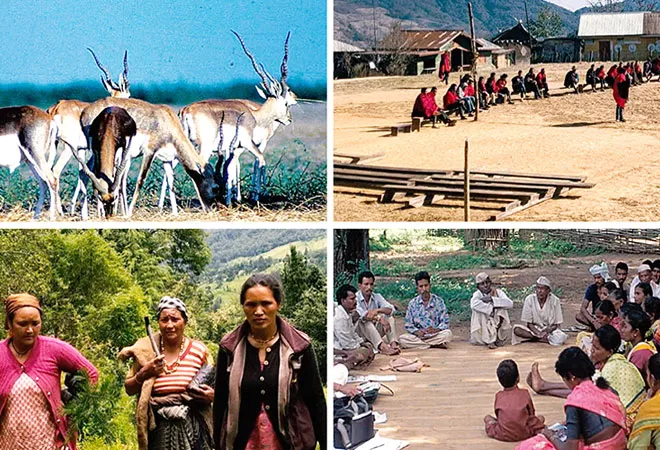

Since time immemorial, IPLCs have conserved their territories through traditional knowledge and diverse systems of governance that sync with the local ecology. Such efforts are persevered till today, but there is an increased role that they play at the global level towards a more secure biodiverse planet while placing livelihoods and cultural diversity at its core.

IPLCs encompass up to 22 percent of the world's land surface, which holds around

80 percent of the planet's biodiversity. The growing body of evidence demonstrates that the majority of the lands under the stewardship of IPLCs are in ‘

good ecological condition’ and the need of the hour is the recognition of their rights over their territories and

support to equitably and effectively participate in these global efforts.

The territories and areas conserved by IPLCs that are globally known as

‘ICCAs’ are much more than species and ecosystem conservation. There exists a deep connection between the area and local communities, which is intrinsically linked to the maintenance of biocultural landscapes and seascapes rooted in socio-economic, cultural, ecological, spiritual, and political spheres of their lives and

identity.

The growing body of evidence demonstrates that the majority of the lands under the stewardship of IPLCs are in ‘good ecological condition’ and the need of the hour is the recognition of their rights over their territories and support to equitably and effectively participate in these global efforts.

In India, such territories are widely called Community Conserved Areas (CCAs).

Why the need to advocate for CCAs?

Although, Protected Areas (PA) have been significant in saving certain species from the verge of extinction and protecting ecosystems from mega-development projects due to their legal status, but the inherent assumption concerning the nature of most PAs comes from the colonial notion of conserving biodiversity that separates humans from nature and leaves little to no space for

co-existence.

Alternatively, CCAs are territories that act as corridors for animal movement and can complement PAs with a focus on landscape management. Additionally, biodiversity conservation is not always a primary objective for communities; however, it is an integral part of their livelihoods or cultural beliefs by virtue of existing systems, which makes

CCAs a key entry point in bridging the gap between local livelihoods with conservation.

CCAs are also essential in maintaining

ecosystem services such as soil conservation, water security, gene pools, and can facilitate linkages between agricultural biodiversity and wildlife, thereby providing larger water/landscape integration.

A

report (2012) by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in partnership with MoEF and the governments of Odisha and Madhya Pradesh documented 52 CCAs in the two respective states. It points out that CCAs have played a central role in biodiversity conservation and have shown the way towards climate change mitigation through diverse governance systems.

Biodiversity conservation is not always a primary objective for communities; however, it is an integral part of their livelihoods or cultural beliefs by virtue of existing systems.

The benefits and values that CCAs encompass resonate directly with numerous targets under GBF. Thus, there is a need to recognise CCAs as a separate legal entity in the Indian context, which will also facilitate a rights-based approach in the implementation of the GBF.

Examining Target 3 under GBF

Target 3 has been widely debated since its inception and it has the potential to bring CCAs to the forefront of conservation laws and policies. Essentially, it calls for the conservation of ‘at least 30 percent of terrestrial, inland water, and of coastal and marine areas’ through the PA network and other effective area-based conservation measures while ensuring the recognition of rights of IPLCs over their territories.

According to MoEFCC, around

27 percent of the country’s geographical area is under conservation. While, at a surface level, this figure might be intriguing but as argued above, given the nature of PAs and how they are notified, there exists a gap between the fulfilment of Target 3 through the PA network and the human rights-based approach that is vehemently advocated under GBF.

There is another question in Target 3 that poses great uncertainty for India. How do we bring areas apart from PAs into conservation that helps in meeting the required target? At a global level, recognising Other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) as a separate category has been instrumental in bringing diverse worldviews on conservation. However, it is ultimately the prerogative of the national governments to ideate on the definition, legal implications, and their engagement vis-à-vis the process of recognition and role of IPLCs in the policy discourse.

Although there are a few provisions (such as Biodiversity Heritage Sites under BDA 2002 and Community Forest Rights under FRA 2006) under the existing Indian laws that are pertinent, there is no national-level policy to recognise CCAs as a separate legal entity.

It is ultimately the prerogative of the national governments to ideate on the definition, legal implications, and their engagement vis-à-vis the process of recognition and role of IPLCs in the policy discourse.

This would have been a great opportunity for India to lead the discourse on biodiversity conservation and meet the GBF targets on ground rather than meeting them only on paper, which might be the case given how OECMs have been conceptualised in the country with no clarity on safeguards for such recognised areas in case they are notified as Pas in the future.

Experiences of community leaders

Malika Virdi, who was the sarpanch of

Sarmoli Jainti Van Panchayat in Uttarakhand, recalls the introduction of the Joint Forest Management (JFM) scheme in the state where people were invited to collaborate with the Forest Department (FD) towards the protection and management of forests; however, the balance of power in the decision-making was skewed towards the FD who dictated land use.

She mentions that “once you displace local use then you also disincentivise the communities to conserve”. She emphasises the threats from multi-purpose projects that don’t account for the areas managed by local communities but often views such areas as ‘wastelands’.

Orans in Rajasthan that are protected for their sacred values and recognised as repositories of biodiversity and providers of ecosystem services also face similar threats. It is estimated that there are over 25,000

Orans in Rajasthan, including

Gauchars (grazing lands), which together occupy a significant

5 percent of the total land area of the state.

Aman Singh, leading the advocacy efforts to conserve Orans, raised the issue of encroachment on Oran lands by solar and wind energy projects, especially in the districts of Barmer and Jaisalmer. It was only until the

order of the Supreme Court of India in 2018 that sacred groves such as Orans and De-vans came to be accepted under the category of ‘deemed forest’, which might act as a safeguard against unbridled mining. However, the term is ambiguous and different people interpret it differently. The response of the government in implementing the law has also been quite poor as only one committee has been formed in the last five years but there has not been any other follow-ups. In the last five years, 88,903 hectares of forest have been

diverted for ‘development’ projects that include road projects (19,424 ha.), and mining (18,847 ha.) etc. Although the provisions under the Forest (Conservation) Act 1980, facilitate the decisions taken by the government, the issues of forest rights, irreversible biodiversity loss and compensatory afforestation, particularly as monoculture to sequester carbon, needs to be discussed with gravitas vis-à-vis GBF.

The response of the government in implementing the law has also been quite poor as only one committee has been formed in the last five years but there has not been any other follow-ups.

The fisherfolk communities inhabiting

Loktak lake in Manipur, have constantly battled against the evictions by the state and the development projects it continues to push. There exists a legislation called the Loktak Lake Protection Act (2006) but it essentially hinders the local communities from using resources for their subsistence needs.

Salam Rajesh, who has been integral in championing the cause of involving the local communities in the decision-making process says that “the communities know how to handle biomass, they know about the seasonal winds, the breeding season of fingerlings and traditional ways of managing biodiversity. It might not be scientific but look at the traditional wisdom of these communities and the effectiveness of their efforts on the ecology of the lake. So, in a way, it is scientific.”

Although India has officially acknowledged

OECMs as a category to recognise diverse models of conservation, it only pays lip service to the efforts of local communities in conserving their territories. This is reflected through some of the above-mentioned examples as well as a CBD

report (2012) and an India-level

directory (2009), bringing issues of restrictive laws and policies, the lack of tenurial security and threats to people and biodiversity due to mega-development projects to the forefront, especially at a time when ‘biodiversity is deteriorating worldwide at rates

unprecedented in human history’.

Conclusion

There is an urgent need to review the provisions of current legislation such as the ‘Community Reserve’ category under the Wildlife Protection Act (1972) where the ambit of tenurial security for local communities needs to go beyond private lands and include government-owned lands as well. Fundamentally, we need to incorporate place-based community-led approaches to biodiversity conservation in our laws.

The recognition of CCAs through laws and policies will enable a process-oriented approach towards achieving the targets under GBF.

Currently, data has become the language to communicate policy negotiations (also reflected in Target 21), so civil societies needs to ensure that documentation of CCAs is integrated with open-source web portals that become an important tool in evidence-based research and advocacy and provide the decision-makers, practitioners and general public with information and knowledge about diverse governance systems and the role of traditional knowledge in biodiversity conservation.

The recognition of CCAs through laws and policies will enable a process-oriented approach towards achieving the targets under GBF. The conceptualisation of ICCAs reflects the need to be more diverse in our understanding of conservation and recognise the rights of IPLCs as custodians of biodiversity.

Now, the only question is whether the political goodwill can percolate in the Indian context and materialise into tangible actions at the grassroots in a way that supports and strengthens such diverse and local institutions.

Rudrath Avinashi works with Kalpavriksh and is part of the team that coordinates the South Asia regional-level chapter of the ICCA Consortium. He is also a member of the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework ( PREV

PREV