The Cabo Delgado province in northwestern Mozambique, bordering Tanzania, was once the heartland of Mozambican national liberation struggle. It is in this province where guerrillas fought Portuguese colonialism, sowing the seeds for socialism in Mozambique. The province catapulted into prominence in 2010 when United States energy company – Anadarko - discovered major gas reserves in the Rovuma basin, hidden beneath offshore deep waters in the Indian Ocean. The following year, Italian energy company ENI also found a massive gas field in the area. These valuable natural resource discoveries attracted the interests of international capital and Mozambique was soon touted to become a gas supplier to the world. Since the discoveries, foreign energy companies have been continuously poaching for lucrative contracts. Many hoped the discoveries would bring prosperity to the impoverished region. But the arrival of the gas industry has failed to bring prosperity to local community. Rather, it has led to large-scale forced displacement, loss of livelihoods, inadequate compensation, and increasing violence from local armed insurgent groups. The curse of natural resources has struck.

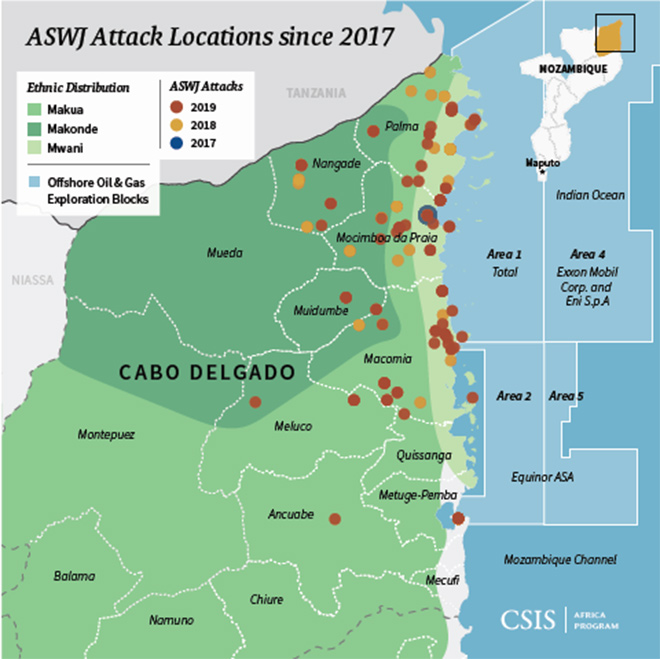

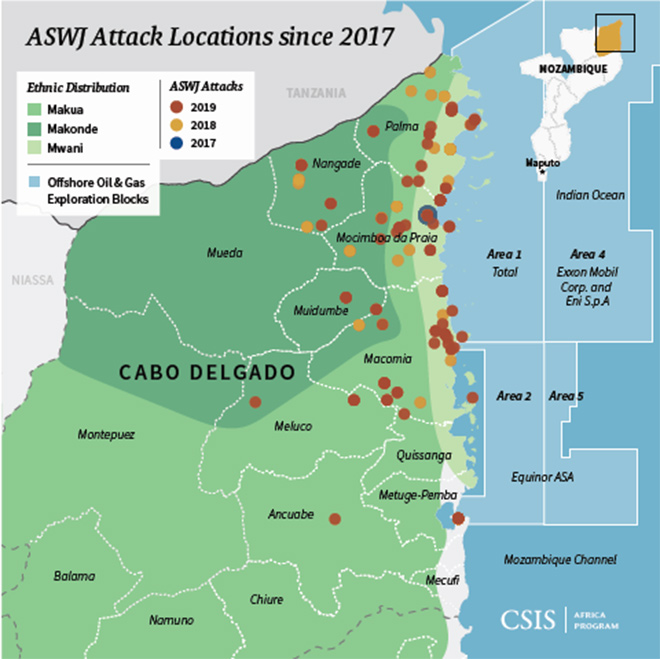

The situation started to worsen from October 2017 when Islamic extremists simultaneously launched violent attacks on police and military installations in the province of Cabo Delgado. What started as a local religious sect has turned into a violent Islamic insurgency, led by local jihadist group commonly referred to as Ahlu Sunnah Wa-Jama’a (ASWJ) – largely translated means adherents of the prophetic traditions. However, there is no consensus on the name or construct of the group committing these atrocities. Some locals call it ‘al Shabaab’ (the youth) while others call it ‘Swahili Sunna.’ The group’s activities have been concentrated on the coast of Cabo Delgado stretching from Pemba to the Tanzanian border. More worryingly, the ASWJ has possibly developed linkages with the dreaded international Islamic terrorist organisation – Islamic State (IS). Both the Islamic State and its offshoot – Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP) have claimed responsibility for several attacks. This raises questions for analysts about how IS and ASWJ are related. Is Islamic State simply claiming responsibility to boost its public stature or is the ASWJ a local affiliate of the IS? Whatever the answers might be, one thing is certain: the ASWJ is essentially a domestic phenomenon rooted in Cabo Delgado, one that has morphed into a brutal terror campaign.

The attacks mainly started in response to weak governance and rule of law, and a desire to be free of an alleged ‘corrupt’ system. In addition, years of grinding poverty, and a deep sense of marginalization and inequality between locals and the elite down south in Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, and elsewhere in the country, contributed to the problem. The locals claimed they were being denied economic opportunities and a right to choose the way of life they believed in.

Source: CSIS Africa Program, October 2019

Source: CSIS Africa Program, October 2019

These domestic compulsions have forced disenfranchised local youths to take up arms and fight for a cause they deem is just. At the heart of the problem lies the question of mass appropriation and redistribution of wealth. The insurgents believe that the government is ‘unfair’ as it ‘humiliates’ the poor and allocates money to the rich. Their desire is to implement an ‘Islamic government, not a government of non-believers (Kafir).’ In addition, climate changes have further exacerbated existing tensions. The 2019 cyclones Idai and Kenneth, which came in quick succession, were devastating to local communities. What started as a simmering Islamic revolution in a remote corner of Mozambique has now erupted into open warfare, especially since March 2020, with reports of beheadings, massacres, and brief seizure of two towns in Cabo Delgado province – Mocimboa da Praia and Quissanga.

Government’s response

Thus far, the Mozambican government’s responses have been extremely militarized and heavy-handed, often riddled with allegations of human rights abuses. It took days before any public acknowledgment of the attacks or presence of ISIL affiliated fighters in Mozambique by President Filipe Nyusi was forthcoming. Since the first reported incidents, the government shuttered mosques and has carried out large-scale arbitrary detentions and in few instances, extrajudicial killings. Press freedom has also been severely threatened and restricted. The government’s initial counter-insurgency tactics mostly depended on thuggish police action, and hired Russian mercenaries – Wagner Group. Most of the security forces are not trained in counter-extremist operations, and lack equipments and intelligence information to effectively fight the ASWJ alone. In some instances, security forces did not defend or resist against the occupation of the two towns. Some even apparently shed their uniforms to blend in with local civilians to avoid combat. After suffering tactical defeats and losses from ambush attacks, the Russian mercenaries – who do not understand local culture or traditions and are ill-accustomed to fighting in a jungle environment – are now backpedaling.

For any responses to succeed, the Mozambican government needs to develop a holistic whole-of-government counter-insurgency strategy by integrating the different government ministries into its response strategies. In these times of coronavirus-induced financial strains, the government needs to identify areas where financial assistance by international partners would be most impactful – be it equipments or intelligence information sharing. Accountability within the security forces for the treatment of civilians also needs to be reinforced. What the Mozambican government needs an approach that incorporates proportionate military actions and programs that will address the fundamental economic and societal issues that drove the youths of Cabo Delgado to take up arms. Building dialogues between community leaders (especially the neglected Muslim-minority Mwani ethnic group from where most recruitment has taken place) and international organisations is essential.

The nexus

What complicates the insurgency in Cabo Delgado is the brazen and unabashed undertones the recent spate of attacks has taken shape. The attackers have openly asked civilians to reject the flag of current ruling party Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO). More worryingly, very less is known about ASWJ and its political motives and agenda. Most of the ‘taking credit’ for the attacks has been ostensibly done by IS and its regional offshoot ISCAP. Moreover, the Mozambican government completely restricts access to the conflict zone for researchers or media persons. Freelancers and foreign correspondents based in the country are charged lofty amounts for media accreditation. This makes it nearly impossible to ascertain a clear link between the ASWJ and IS or ISCAP.

Although there is a dearth of evidence to directly link the ASWJ with IS, borrowing a global dimension as an IS franchise will boost its prestige, in addition to potential transfer of deadly technologies as well as a ready supply of reinforcements. The insurgency threatens to destabilize regional security and stability and can have a ‘spillover effect’ in the neighbouring East African Community countries. By enforcing repressive tactics, the Mozambique establishment risk repeating the same mistakes in responding to extremist insurgencies as was the case in Nigeria (Boko Haram) and Somalia (Al Shabaab). Heavy-handed repression is most likely to backfire and will only serve to amplify religious and ethnic tensions. Such situations provide fertile breeding grounds for extremist recruiting. Lessons unlearned will prove fatal.

The ASWJ group is unorganized and does not have a clear hierarchy. There are no poster boys for the group. Rather, in recent weeks, it has become immersed in smuggling operations through gems, timber, and drugs. Such tactics does not show sophistication of a cross-border terror network with credible links to international connections (i.e. Islamic State). Rather, the ASWJ is likely to remain a localised organisation, one that is caught between organised crime and extremism.

Possible Indian collaboration on counter-terror

As the insurgent attacks continue to grow in both frequency and intensity, the Filipe Nyusi government has reached out to foreign partners for security assistance. Apart from Russia, Mozambique has hired mercenaries from South Africa and United States to fight the insurgents. Another possible security partner could be India, with whom Mozambique has long-established defence partnership. Both have been victims of radical terrorism from extremists for many years. Therefore, cooperation on counter-terrorism operations has figured extensively in our recent engagements. Mozambique was one of the participating nations’ in the inaugural Africa India Field Training Exercise (AFINDEX-19) and the first ever India Africa Defence Ministers Conclave held in February 2020. Defence Minister Rajnath Singh’s visit to Maputo in July 2019 was significant as both partners agreed to work together towards tackling the growing menace of terrorism and radicalization. India has been an ardent supporter of Mozambique’s Disarmament, Demobilisation, and Reintegration (DDR) peace process and also handed over 44 SUV to Mozambique’s National Criminal Investigation Agency in an effort to boost safety and security of the Mozambican police forces. The best way India can help Mozambique in its counter-terrorism operations is by assisting Mozambican security personnel with communications equipment, i.e. robust sharing of information, intelligence, and surveillance, in its fight against violent insurgency in Northern Mozambique.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV