This year’s COP27 climate conference elaborated on the growing inequalities, which were exacerbated by the COVID pandemic. While 51 percent of the world’s population living in high- and upper-middle-income countries is responsible for 86 percent of

global emissions, the 49 percent living in low- and lower-middle-income countries contribute only 14 percent. Similarly, while high- and upper-middle-income countries administered about 214 doses of the

COVID vaccine per 100 people, low-income countries managed only 31 doses. The daily per capita

protein consumption in low-income countries is only about 60 percent of that seen in high-income countries, and globally, about

800 million people are undernourished, of which almost 90 percent live in Asia and Africa.

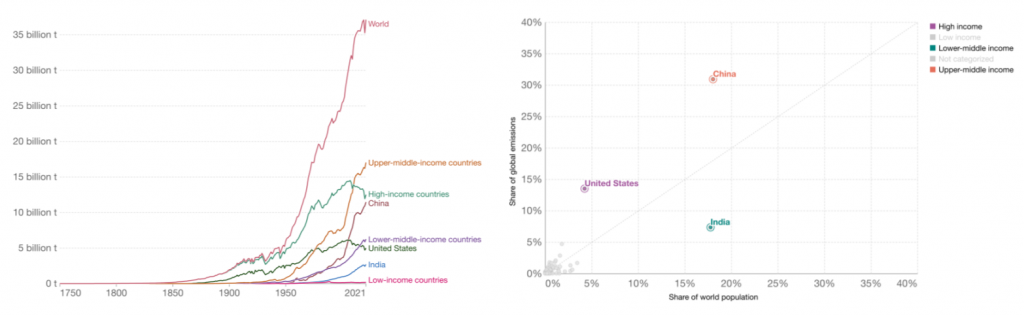

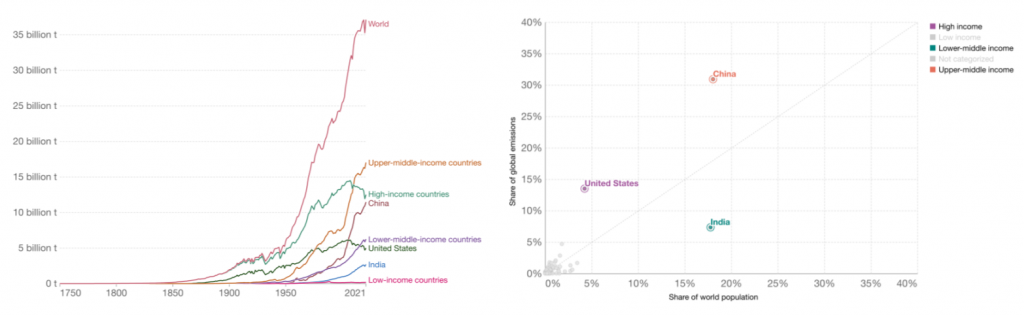

Measurements show the top three carbon dioxide (CO

2) emitting countries to be China, the United States (US) and India. Of the 37.1 billion tonnes of CO

2 emitted in 2021, China contributed 11.5 billion tonnes (31 percent of global emissions), the US, 5 billion tonnes (13.5 percent) and India, 2.71 billion tonnes (7.3 percent) (Figure 1). However, a different picture emerges when

per capita emissions are calculated— the US emits nearly 14.86 tonnes; China, 8.05 tonnes; India, 1.93 tonnes. Against a world average of 4.69 tonnes of CO

2 emissions per capita in 2021, high-income countries produced 10.727 tonnes, upper-middle-income countries produced 6.69 tonnes, whereas lower-middle-income countries produced 1.83 tonnes and low-income countries 0.28 tonnes. However, climate-related impacts go the other way,; and for sustainable mitigation, this global inequity must be addressed.

Figure 1. (Left) Growth in CO2 emissions coming from China, USA and India against global emissions and other world groupings by 2021. (Right) Plot of share of global Co2 emissions in 2021 versus share of world population.

Figure 1. (Left) Growth in CO2 emissions coming from China, USA and India against global emissions and other world groupings by 2021. (Right) Plot of share of global Co2 emissions in 2021 versus share of world population.

Decoupling of economic development and emissions

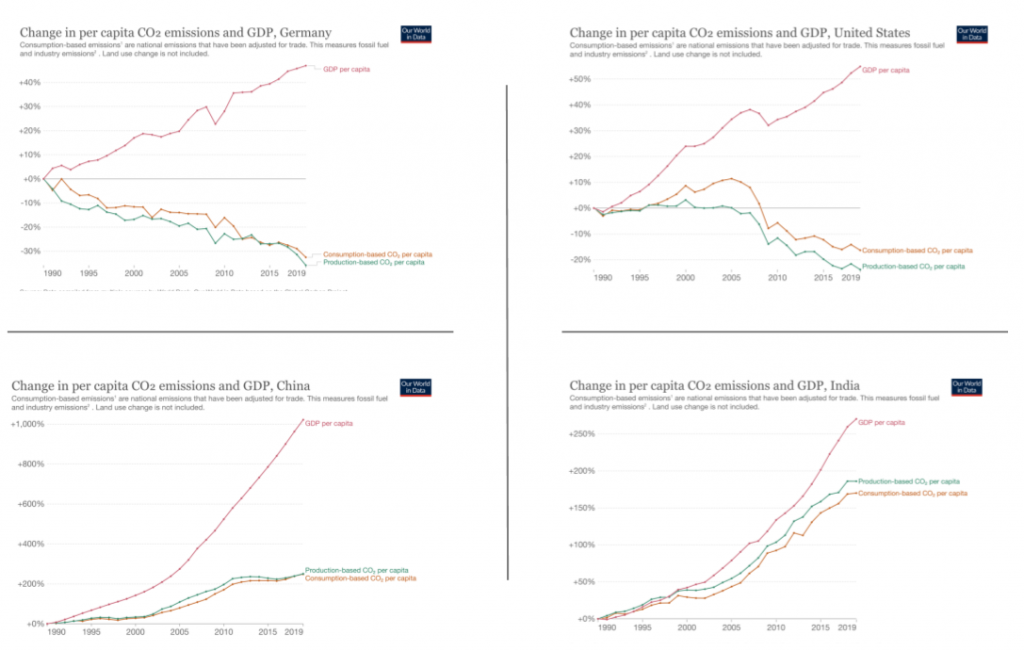

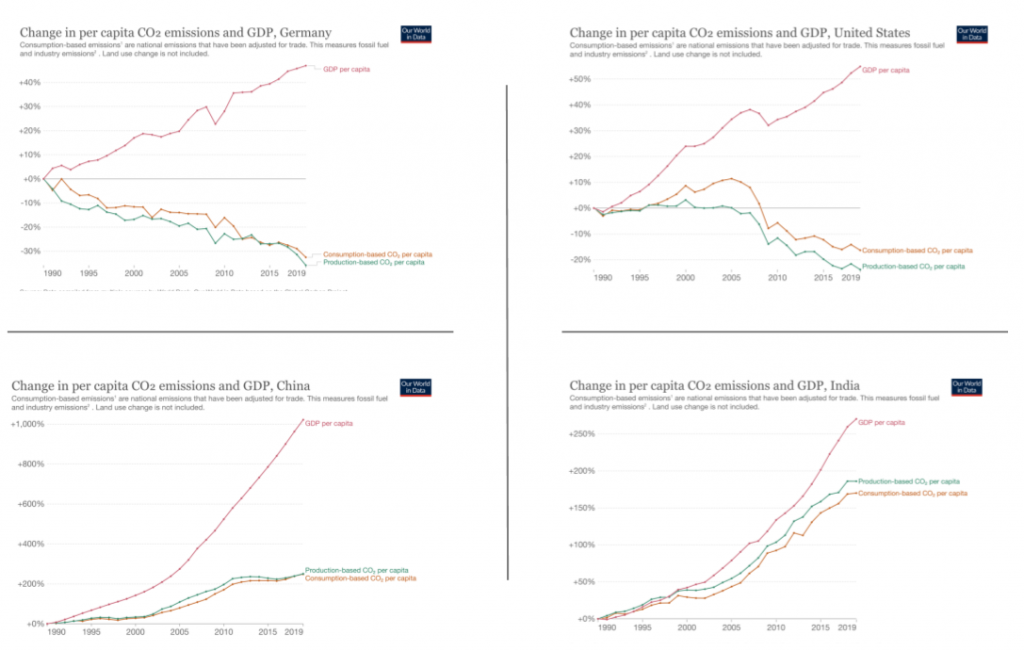

Prosperity is historically linked to GHG emissions. Increased production pushes up the GDP but also increases emissions due to energy needs and use of fossil fuels. Increased prosperity also pushes up consumption, which comes at the cost of emissions. But, this direct relationship is no longer true as several high-income countries have managed to

decouple economic growth from emissions. Over the past 30 years, several Western European and Scandinavian countries have increased their GDP substantially while reducing emissions. Others such as the US have done this more recently, even for consumption-based emissions and not just production-based emissions, which accounts for moving production (and its resulting emissions) overseas. However, the other big emitters—China and India—continue to show concordance between GDP growth and increasing emissions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Changes in per capita CO2 emissions and GDP show decoupling for some countries (e.g., Germany, USA) but not for others (e.g., China and India).

Figure 2. Changes in per capita CO2 emissions and GDP show decoupling for some countries (e.g., Germany, USA) but not for others (e.g., China and India).

The key reason rich nations are able to decouple their economic growth from emissions is

replacing fossil fuels with low-carbon energy. Producing more energy, without the customary emissions can make a real impact if we can decarbonise quickly, and across more countries. This could be done by

reducing costs of low-carbon technologies.And this is where India can make a real impact with the projected increases in capacity and investments in

renewables and

hydrogen. Developing countries will need investments to transition from fossil fuels to clean energy, and decouple GDP from emissions. Due to their

historical contributions to emissions, it makes economic, ecological, and most importantly, ethical sense for rich economies to come up with the money.

Developing countries will need investments to transition from fossil fuels to clean energy, and decouple GDP from emissions.

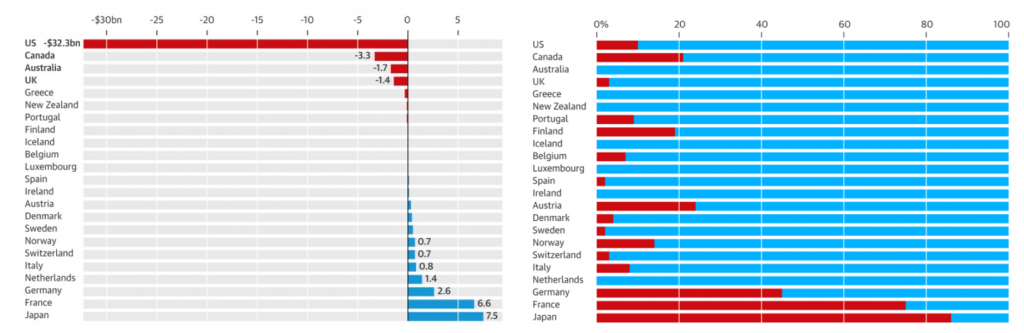

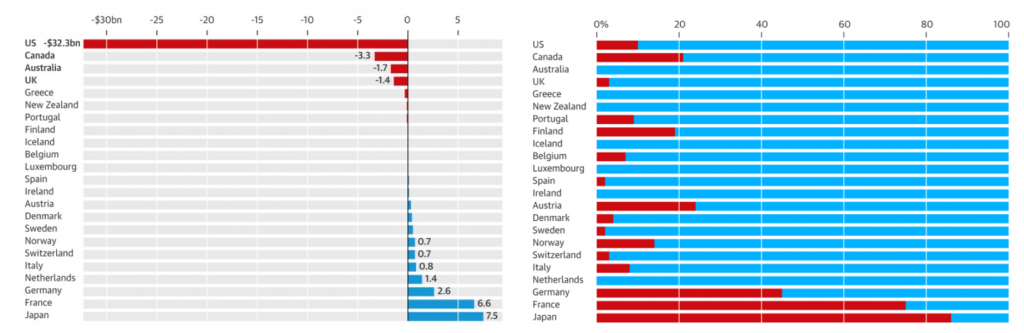

But like vaccines, climate commitments have faced challenges. At COP15 in 2009, developed countries agreed to mobilise US$100 billion annually by 2020, to help developing countries adapt to climate change. Between 2013 and 2020, resource US$50-80 billion annually, but the actual value was much less since most came as loans. The

Indian Finance Ministry disputed the estimated US$57 billion climate finance in 2013-14, saying that the real figure was only US$2.2 billion. A recent

assessment by Climate Brief showed how most rich nations fell short of their fair share of climate funding. The US led with a US$32.3-billion deficit, followed by Canada (US$3.3 billion), Australia (US$1.7 billion), and the UK (US$1.4 billion). Some countries like Japan, France, and Germany provided more than their assessed share, but largely as loans and as not grants (Figure 3). Just as vaccine donations through

COVAX could barely vaccinate 20 percent of the populations of low-income countries, the US$100-billion annual fund falls short of addressing climate change in an equitable and sustainable manner. New data suggests that

by 2030, about US$2 trillion will be needed annually to help developing countries reduce their GHG emissions and cope with the effects of climate breakdown.

Figure 3. (Left) Climate finance shortfall or surplus in 2020 for countries based on their assessed contributions to the $100 billion target. (Right) Percentage of climate finance from 2012 to 2020 given as loans (in red) and grants (in blue).

Figure 3. (Left) Climate finance shortfall or surplus in 2020 for countries based on their assessed contributions to the $100 billion target. (Right) Percentage of climate finance from 2012 to 2020 given as loans (in red) and grants (in blue).

COP27 was a missed opportunity

A

mixed result of COP27 made it clear that while the tools are available, the will to act proactively is missing. The “loss and damage” agreement to help developing countries overcome climate impacts was a breakthrough at COP27. How will loss and damage be quantified, the funds disbursed, and who will pay the compensation remains unclear. Nature and biodiversity were recognised as key resources with a strong political will to

protect forests, and food finally made it on the COP27 agenda through the Food and Agriculture for Sustainable Transformation (

FAST) Initiative. However, there was no progress on cutting fossil fuels, and the US$100-billion Climate Fund continues as a largesse of rich nations.

Although several options exist to address the troika of climate change, health, and food systems, there are difficulties in developing implementable and sustainable policies. Policymakers face interlocking decisions that are often unpopular. For example, reducing meat in the diet lowers emissions but also impacts the livelihood of livestock farmers. The climate, health, and food communities suffer from fragmented decision-making, vested interests, and power imbalances, and a lack of joint vision and leadership. Understanding the who and how of decision-making, the science of global warming and the implementation pathways are important. We must also improve communications around the linkages between climate, health, and food, and address it as one system.

The climate, health, and food communities suffer from fragmented decision-making, vested interests, and power imbalances, and a lack of joint vision and leadership.

The

UN Secretary General rightly summed it up at the opening of COP27 when he said, “We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot on the accelerator.” He also added that “The global climate fight will be won or lost in this crucial decade—on our watch.”

Time is running out. We must act proactively and not just react to ‘loss and damage’.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This year’s COP27 climate conference elaborated on the growing inequalities, which were exacerbated by the COVID pandemic. While 51 percent of the world’s population living in high- and upper-middle-income countries is responsible for 86 percent of

This year’s COP27 climate conference elaborated on the growing inequalities, which were exacerbated by the COVID pandemic. While 51 percent of the world’s population living in high- and upper-middle-income countries is responsible for 86 percent of

PREV

PREV