The European Union (EU) is unleashing its 12th round of sanctions against Russia; this sanctions package would target both imports and exports, family members of the Kremlin elite, and would focus on secondary sanctions. The evolution of sanctions against Russia has been lethal, and directly proportional to its geopolitical adventurism in Eastern Europe. The Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 saw the commencement of economic sanctions by the West—EU, the United States (US), New Zealand, Australia, and Canada—against the Russian Federation. Since then, Russia has been drifting away from the international political economy.

The coming year will mark a decade since the first tranche of sanctions was imposed. Sanctions, dubbed as ‘economic warfare’ by Woodrow Wilson, aim to subdue an aggressor in the international system using economic means, curtailing the importing/exporting power of a nation. Economic warfare can be launched through embargos, financial exclusion, travel bans, and restricting exports and imports of a state. The history of the imposition of economic sanctions goes back to ancient times, as far as 432 BC when Athens imposed economic sanctions in the form of the Megarian import embargo against the city-states that refused to join the Athenian-led Delian league. In the late 19th century, sanctions were used in the form of export controls on strategic supplies or embargos and blockades on the target countries. France sanctioned Britain during the Napoleonic wars. This form of sanctions remained through the 19th century and received institutional backing with the emergence of the League of Nations. Economic sanctions were used against Italy for its Abyssinian conquest, and against Japan to dissuade it from further eastward expansion. With the end of the Second World War, the League was replaced by the United Nations, with a larger mandate. Between 1950 to 2022, there have been more than 1,325 economic sanctions.

The history of the imposition of economic sanctions goes back to ancient times, as far as 432 BC when Athens imposed economic sanctions in the form of the Megarian import embargo against the city-states that refused to join the Athenian-led Delian league.

With the turn of the century, financial sanctions were introduced, where banks and individuals were targeted with asset freezes. A target state would be deprived of access to the sender—a nation that imposes the sanctions—currencies. Financial sanctions were first introduced against North Korea and were widely used in the Iranian campaign. Since then, the complexity of sanctions has increased with time, giving compliance officers of companies the Herculean task of keeping up with the economic sanctions imposed against a nation, firm, and individual.

The sanctions imposed on Russia need to be analysed, as it manifests the fragmentation of the geoeconomic world order, and exemplifies how sanctions are perceived by the financial institutions of various countries. The imposition of the sanctions on Russia has to be divided into two periods: the first period will look at the sanctions imposed on Russia from 2014-2021, and the second period will look at sanctions imposed since the invasion of Ukraine.

2014 sanctions

Unlike the 2022 sanctions, the 2014 economic sanctions are not unilateral. The EU did not whole-heartedly impose sanctions on Russia due to its economic integration with the Russian Federation’s energy value chains. For instance, the US, Canada, and Australia sanctioned Igor Sechin (CEO of Rosneft), Alexey Miller (CEO of Gazprom), and Vladimir Yakunin (the then CEO of Russian railways). However, the EU did not sanction them. The EU nations were scrambling to complete the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, as the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) was closely monitoring the minute aspects of the project to impose secondary sanctions on the Western firms. In 2015, sectoral sanctions were imposed on Russia, coincidentally with the downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 by Russia-backed separatists. During this phase, the Russian energy sector, the defense sector, and elements of the financial sector were sanctioned. Sectors of the Russian economy were divided into rent-generating sectors (Sector A)—oil, gas, construction of nuclear power machinery, agricultural and defense production—and rent-seeking sectors (Sector B)—automotive industry, aviation, shipbuilding, pensions, and oil and gas operative equipment. Sector B depended on the rents of Sector A. At the beginning of sanctions, the economy was being re-configured and the Kremlin introduced import substitution policies in sectors which was highly dependent on the West. During this period, the poisoning of Sergei Skripal attracted further sanctions on the Russian state and saw minor intensifications till the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

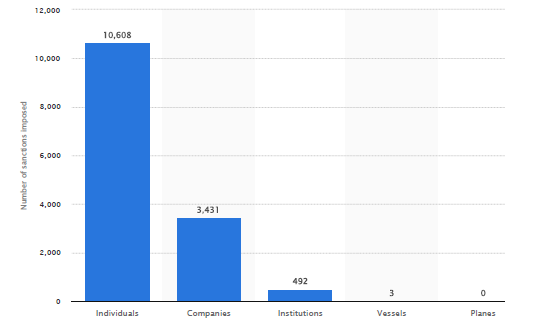

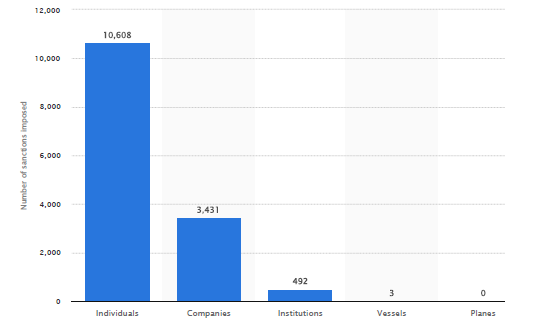

Fig 1.1: Total number of list-based sanctions imposed on Russia by territories and organizations worldwide from February 22, 2022, to February 10, 2023, by target.

Source: Russia; OpenSanctions.org; Corrective; February 22, 2022 to February 10, 2023

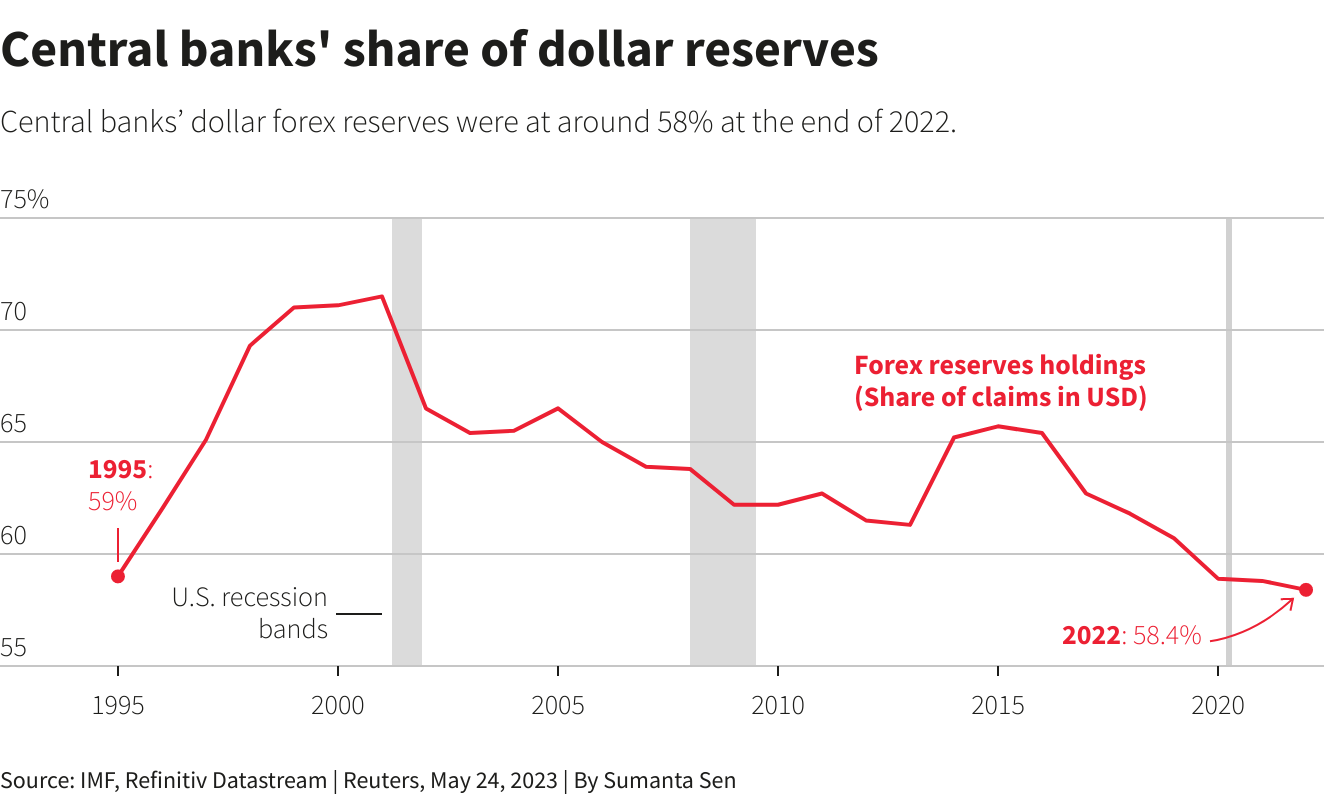

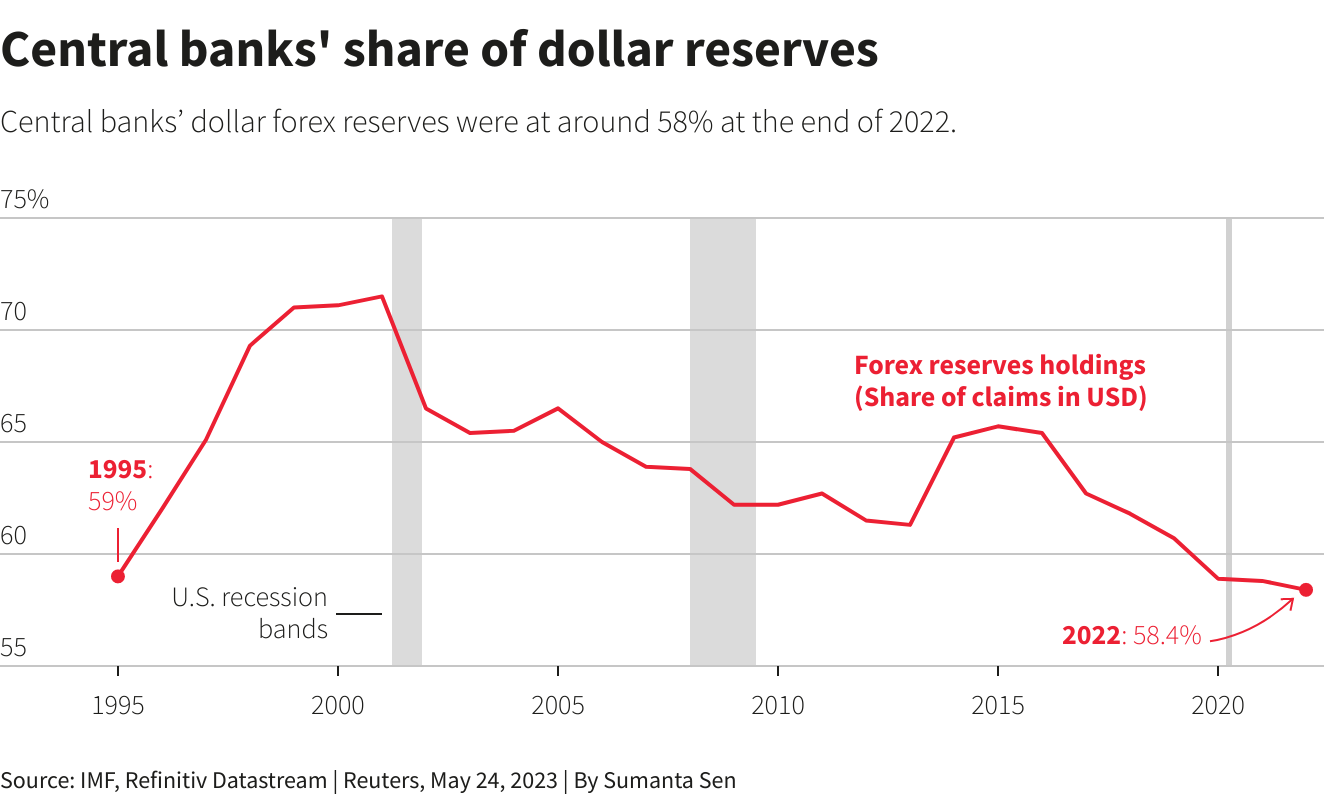

Fig:1.2: Share of dollar reserves (signaling a de-dollarization effect) 2023.

Source: Reuters.

2022 sanctions

Hours after the first troops crossed over the breakaway regions of Ukraine, the US, United Kingdom (UK), Australia, and the EU sanctioned Russian banks. Along with this, Canada and New Zealand imposed export controls on software, equipment, and technology. The EU issued “targeted restrictive measures” against 27 high-profile individuals and entities and “measures” against all members of the Russian State Duma. Even broadcast journalism fell victim to sanctions when the EU banned Sputnik and Russia Today. On 8 March, the US banned the import of Russian oil, gas, and other energy sources. By April 2022, there was a proposed ban on Russian coal by the EU and a further ban on Russian and Russian-operated vessels from entering the European Union countries. Four major banks: VTB, Sovcombank, Novikombank, and Otkrite Financial Corp, which represent 23 percent of the country’s market, share were sanctioned. By June 2022, the European Union adopted its sixth package of sanctions, which saw Sberbank—the credit bank of Moscow, excluded from the SWIFT. By October 2022, the oligarchs, senior military officials, and members of the legislative assemblies of the occupied territories were sanctioned. By 2 December, a price cap of US$60 was set as the price for Russian crude. Nearing a year after the invasion, the G7 agreed on two price caps for petroleum products originating from Russia. Around the same time, the EU banned oil, gas, and other refined petroleum products. Russia’s FATF (Financial Action Task Force) membership was suspended. By mid-2023, secondary sanctions were imposed on firms based in Türkiye and Dubai involved in re-exporting and in the trans-shipment of Russian oil below the price cap. To sum up, Russian finance, energy, civil aviation, defense, trade, and technology were sanctioned by the West. The intent of the post-invasion sanctions was akin to the Iran sanctions package, i.e., to strangulate the Russian economy into coercion. However, this did not happen, as the Central Bank of the Russian Federation had been preparing for such an economic configuration since 2014.

The intervention of the Central Bank and de-dollarisation

Even before the war, the Central Bank aimed to reduce the dependence on the US dollar. These efforts were accelerated by the third quarter of 2022. The share of dollars and euros is declining in the foreign reserves of Russia; one year since the invasion, transactions in dollars and euros have declined from 52 percent to 34 percent and from 35 percent to 19 percent respectively, while the yuan’s share has skyrocketed from 3 percent to 44 percent, and only increasing. At present, Russia holds US$28 billion in assets and reserves with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), US$145 in gold reserves, and US$20 billion in Indian rupees, apart from the frozen assets.

By mid-2023, secondary sanctions were imposed on firms based in Türkiye and Dubai involved in re-exporting and in the trans-shipment of Russian oil below the price cap.

At the current pace of de-dollarisation and the subsequent Yuanisation of the Russian economy, Russian reserves and payments will be influenced by the policies of the People’s Bank of China. While sanctions are weakening the ruble, the yuan’s influence is increasing, and, over a period of time, the yuan has the potential to become a global reserve currency. China’s cross-border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) dubbed as the Chinese version of SWIFT has seen a 75-percent increase in the transactions completed in 2022 in comparison to 2021. Despite the volume of trade being marginal in comparison to SWIFT which moves US$5 trillion a day, the Chinese yuan and CIPS are being favored by several nations and are only set to rise due to the sanctions-happy policies of the US treasury.

Sanctions resilience and busting

Several strategies have been employed to bypass sanctions and continue trade with Russia. Some countries tried legal measures, like Hungary which was able to negotiate an exemption from sanctions for their gas imports from Russia. The share of oil and gas imports from Europe has declined; however, this does not stop nations from buying Russian hydrocarbons. Oil is being re-imported from India, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Türkiye. The latter has dedicated shipping firms that help Russia re-import goods in the Black Sea. In August 2022, Japan’s Liquified Natural Gas volumes in comparison to 2021 increased by 211 percent despite imposing sanctions on Russia. Despite the price cap being imposed to discourage spot trade, some firms still trade Russian oil above the price cap set for Russian crude. The legislation and imposition of sanctions is an easy task. However, the real-time monitoring is a difficult one. To improve import competitiveness, Moscow has placed orders for 29 additional container ships, which are to be delivered this year. These orders would be purchased on behalf of China. This is indicative of the increasing propensity to trade from Moscow. However, despite the resilience mechanisms being set up by the Russian state, it would be incorrect to state that Russia has not been impacted by sanctions.

The share of oil and gas imports from Europe has declined; however, this does not stop nations from buying Russian hydrocarbons.

Conclusion

The sanctions imposed in 2014 gave time for two sides to get acquainted with the new normal. For Moscow, it was to veer back to a cold-war-like geoeconomic configuration and consider a pivot to Asian markets whilst working on import substitution policies. For the West, 2014 was the year that they began thinking about diversifying their energy investments away from Russia. And 2022 was the year when it became clear that the West would have to source its energy from elsewhere. However, both have miscalculated the magnitude of their objectives.

Rajoli Siddharth Jayaprakash is an intern with the Strategic Studies Programme at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV