-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The COVID-19 outbreak spread to Europe earlier this year, and the initial response to the same was driven by urgency due to rapidly spreading COVID cases. This meant that the executive decisions made by national leaders on a country-by-country basis formed the first leg of the response to COVID. However the open borders and travel rules and the nature of goods shipping within the EU also necessitated a collective, pan-European response. While member states are largely responsible for their public health policies, the EU failed to take collective preventive measures to reduce the possibility of transnational infections. Even if the domestic responses of each nation are beyond the typical purview of the EU as a whole, the Union as a regional body did not immediately either curtailed travel or closed its borders, ensured equitable and adequate distribution of medical personnel and equipment; not even it imposed a Union-wide lockdown to minimise the chance of the spread of the virus.

The initial wave of COVID-19 cases in Europe was therefore faced not by the action of the European commission or Parliament, but by the responses of individual nations and leaders. It has even been argued that the subsequent response from the European commission and the approval of the proposed aid package by the European Parliament were simply piggybacking on the initial responses of the EU leaders. This was a significant deviation from the EU’s usual policy of transnational cooperation and regional collaboration. The deviation resulted in excessive strain on the medical and healthcare resources for nations like Italy and Spain.

While this is not to say that the EU must take over the healthcare systems of its member states, supporting them by distributing supplies and establishing a centrally-coordinated plan would have bettered the response to the outbreak and perhaps also de-escalated the rate of infection. Until Italy became the European epicentre of the COVID-19, EU nations were operating almost exclusively on their own, to the extent that Germany imposed a ban on exporting supplies essential to COVID-19. The nation subsequently also prevented critical medical supplies from reaching Italian medical professionals. This incident caused a loss of credibility for the EU in general, and Germany in particular, as the guarantor of European solidarity. However, upon escalation, Germany and France initiated cross-border cooperation by sending protective masks to Italy. Germany then went further, taking in patients from Italy and France.

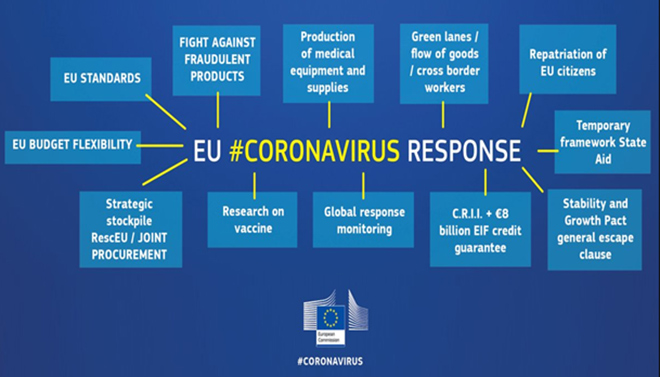

The EU’s collective response to COVID-19 began with the European Commission’s proposals being passed near-unanimously through the European Parliament. The Coronavirus response team established in the beginning of March – led by five commissioners – has overseen the EU’s collective efforts to address the COVID-19 outbreak thus far. The EU instituted a “Coronavirus Response Investment Initiative,” to mobilise funds for national healthcare systems and created a strategic rescEU stockpile of medical equipment (such as ventilators, protective masks etc.) to help countries overcome their shortages. To protect unemployment, the SURE initiative (Support mitigating Unemployment Risks in Emergency) was set up along with a Temporary Framework that ensures the availability of sufficient liquidity to businesses and preserves the continuity of economic activity. Other programmes include Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) worth €750 billion – launched by the ECB in an attempt to counter the monetary risks that may arise during this pandemic – and an advisory panel composed of epidemiologists and virologists to formulate EU guidelines on science-based and coordinated risk management measures.

Source:European Commission’s Response to Coronavirus

Source:European Commission’s Response to CoronavirusTogether with the €120 billion decided on 12 March, the emergency stimulus amounts to 7.3 percent of euro area GDP. Though the initial response was relatively delayed – the COVID-19 cases in Italy began rising rapidly in the third week of February, whereas the EU’s response packages were launched nearly three weeks later – the EU’s subsequent collective response was comprehensive. The closing of outer borders, limitations on travel within the EU, the institution of strict quarantining and social distancing measures, provisioning of essential supplies to the citizens, etc., addressed the major needs of the population. Though the efficacy of these measures can only be gauged with time, the outlook is believed to be favourable.

However, concerns have arisen over the long-term financial implications of the EU’s decisions thus far. The widespread nature of the COVID-19 cases in the EU necessitates a deeper response than the provision of aid and closure of borders. Though priority access lanes now ease the passage of medical supplies, food imports and general exports within the EU, nations are already struggling with the extended nature of this pandemic, and the financial burdens its imposition has created. Various EU-level financial systems have been altered to address this problem. State aid regulations have been eased for member states to subsidise businesses hit by the crisis and general Eurozone rules on government debt sizes have been temporarily suspended, allowing spending as required.

These measures are temporary and to combat the long-term financial risks for national economies as well as for the euro, nations may need to share the debt that will accrue during this crisis. Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte – along with France, Spain and seven other nations – has called for the “debt-sharing mechanism” as a means to raise funds and allow for greater spending on public healthcare in the short-term. The proposal for the conversion of the European Stability Mechanism into a “coronavirus crisis emergency bank” has been fiercely debated and the idea for funding this through “coronabonds” has been met with severe opposition from Germany, Austria and the Netherlands. This opposition to having shared European debt hints at the fractures present in the EU’s previously cohesive structure and a possible weakening in the sense of “European solidarity” at a time when cohesion and collective action are imperative.

Despite a lacklustre initial response, the measures instituted by the EU have provided a solid framework upon which the deeper response to the outbreak can be built. Now, the European Commission and the European Central Bank must act simultaneously to produce favourable results. The need for an effective, pan-European response cannot be understated, but to do so, the equalising nature of the pandemic must first be accepted. The debt-sharing mechanism is one way to ensure the protection of the Euro and allow high spending on public health in the short-term, even if northern EU states must later bail out poorer or worst-affected southern neighbours.

The European Union’s largest challenge is ensuring that the shared financial package is equitably and swiftly distributed despite differing national responses to the outbreak, but its largest roadblock is the quibbling over “debt-sharing.” The pandemic has placed all nations on an even playing field, and they must all be properly equipped to survive it. This is a particularly bitter pill to swallow for those nations that are strongly affected by the outbreak. French President Emmanuel Macron has stated that the failure to agree “could spell the end of the EU,” a sentiment that has been echoed by Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez.

Furthermore, sub-regional blocs that typically exemplify efficient regional cooperation, such as the Visegrád Four – the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia – attempted to come together for a collective response but failed to do so due to the spread of the virus. The uncoordinated nature of their national responses led to the spill-over of the virus across borders, resulting in increased tension between nations. The cooperation that has been effective in peacetime has come under severe strain due to the pandemic.

In the absence of an all-round, cohesive action, rifts in the macroeconomic framework of the EU are beginning to develop, which has opened the door for influence from other nations. Some European nations such as Italy and Spain have begun accepting aid from beyond European borders. Chinese medical teams and supplies have been sent to these countries to assist and are expected to be delivered to France shortly. This has given the Chinese a greater foothold in Europe and has furthered its “the Belt and Road Initiative” agenda, which may potentially compromise the EU’s broader strategic interests.

If the EU is unable to check the spread of COVID cases in Europe, the likelihood of foreign aid will rise and so will the potential for foreign influence. To mitigate this, the EU needs member states to agree on cohesive action and to do so quickly, not only to reduce the massive number of COVID-19 cases, but also to curb the potential of foreign influence in the region.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.