-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

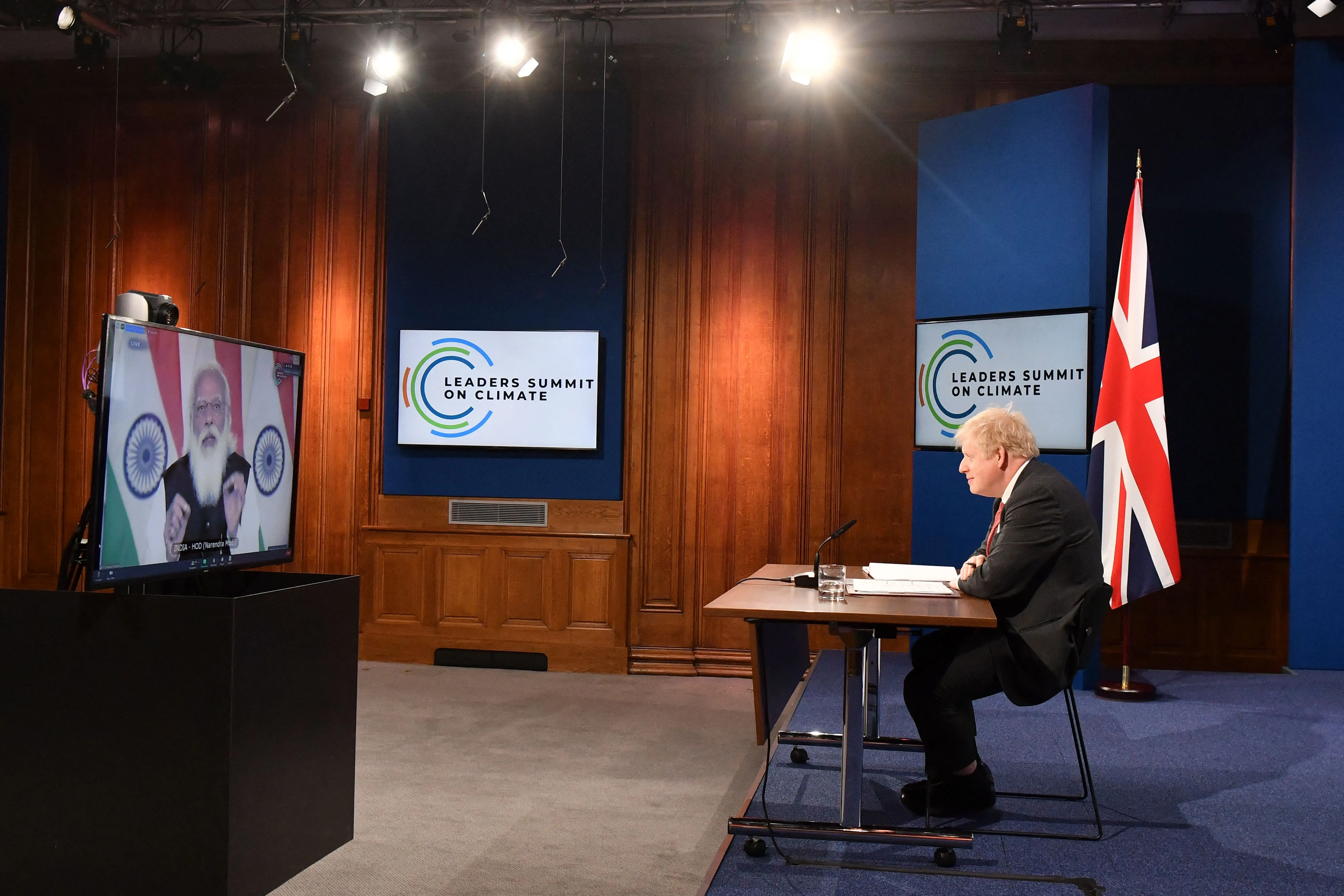

When leaders meet, expect major announcements like a re-set in ties. The “India-UK Roadmap 2030,” unveiled after the virtual summit between Prime Ministers Modi and Johnson on May 4, appears future-perfect. Yet, we can’t be sure if Britain has let go of the past. “There is a whole string of British governments who think there is a special relationship with India. My experience is that the Indians do not have that view of Britain,” says former British chancellor George Osborne.

The summit’s joint statement is long and ambitious, as if Britain and India are specially entitled to hold forth on every issue under the planet. This statement doesn’t state India’s concerns on British interventions in India’s domestic politics—the shielding of anti-India separatists, tolerating violent attacks on the Indian High Commission, providing sanctuary to financial offenders, or holding parliamentary debates on the farmers’ agitation. Kashmir and Britain’s support for the Taliban remain under opaque covers.

When Foreign Secretary Dominic Rabb says, “your politics are our politics,” he means India must live with such interventions. British Pakistanis regularly hold lawmakers to account on Pakistani causes. The interests of British Indians are less aligned with India’s. Thus, the immediate prize of British Pakistani votes outweighs the more distant benefits of a stronger partnership with India. These communities will remain instruments to put pressure on a nation that Britain in the same breath calls “an indispensable partner” and an “international actor of growing importance.”

Nor are Britain’s cost-free statements supporting India’s quest for permanent membership of the UN Security Council (though Britain, like India, supports text-based negotiations on Security Council reforms) matched by intent. No British (or P-5) UN ambassador has made a statement of support for India on the floor of the UN.

During the G-7 summit at Cornwall last week, India signed the “Open Societies Statement”. In past months, there has been breathless talk about the G-7 transforming into a D-10. But non-democratic nations like Russia, Iran and the Gulf monarchies are among India’s strongest partners. Besides, if a coalition against China is the aim, why turn away willing non-democratic states?

India is a revisionist power, and why not? From a reformed Security Council and international financial institutions to revised norms on global warming, India seeks to shape the debate.

For good measure, Robin Niblett, director of the influential Chatham House, in a January 11 paper, observes: “India’s interests rarely align with those of smaller, more economically developed democracies,” and clubs India with China, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey as “rivals or, at best, awkward counterparts”. Strengthening engagement with think tanks does not address the problem, because Britain acts like it is on a higher normative plane.

Why should the structural problems of the relationship surprise us? The world’s 5th largest economy and a P-5 member can’t be happy with an India that is 7th and rising (India had displaced Britain as the 5th-ranked before the pandemic but has now been relegated to 7th). In 2019, India’s share of the world’s GDP was 7.09 per cent and is expected to rise to 7.97 per cent by 2030, making it the world’s third largest economy after the US and China. As Abhijnan Rej says: “Isn’t that future position of India what is allowing New Delhi to improve its present status?” Britain must live with Indian power, so why not nibble away at the seams to delay India’s rise?

This also explains why the USS John Paul Jones in April sailed through India’s Exclusive Economic Zone without consent. Niblett is right—India is different from other democracies like Canada and Australia, whose maritime claims the US also rejects, while refraining from sending warships into their waters and even going public. India is in a different universe when seen from the West.

India is a revisionist power, and why not? From a reformed Security Council and international financial institutions to revised norms on global warming, India seeks to shape the debate. External Affairs Minister Jaishankar calls this a shift from balancing to leading. “The India way,” which he discusses in his book by the same name, counts on India’s ancient precepts to deliver on present ambition. India wants entry into powerful clubs, not an overthrow of the status quo.

Speaking to the British media after the virtual summit, Johnson was quick to trumpet the trade deal. It will create 6,000–6,500 British jobs, more than £ 533 m (US $ 739.2) of new Indian investments in Britain and £ 446 of export deals for businesses, creating over 400 British jobs. Missing was an Indian readout, with one exception. India secured the Migration and Mobility Partnership allowing 3,000 young Indians to avail employment opportunities in the UK yearly without labour market tests. But India had to concede the quid pro quo of accepting undocumented Indians from Britain.

The Enhanced Trade Partnership envisages doubling of trade by 2030 and opens the doors to FTA negotiations. Will Britain lower tariffs to below EU levels, allowing more agricultural exports from India? Will it ease entry of students and skilled workers? Will India lower tariffs? India has scaled back appetitie for free trade deals after mixed returns and has not signed a single such agreement under the Modi government.

India needs to recognise the lack of harmony between different strands of the relationship. Long joint statements and unreachable ambition are not the answer. Arriving at common ground on issues troubling India should be the foremost concern.

Thus, there is a structural problem in the relationship that does not resolve through intentions and papers, and resets and tilts. Past road maps and trade ambitions look like distractions in hindsight. In 2015, the UK–India Defence and International Security Partnership tried to “intensify” cooperation, but results have been modest. The new roadmap may remain just that.

Perhaps, a partnership that creates an additional option on China outweighed immediate gains for India. How would we otherwise explain “diversification of global supply chains” and conduct of joint naval exercises when the British Carrier Strike Group deploys in the Indian Ocean? Combined with Britain’s post–Brexit tilt towards the Indo- Pacific, there is new thinking on both sides. Yet, the lack of a Chinese response to these China–centred moves contrasts with the concerning tone of the Global Times and Chinese scholars when India and the EU announced resumption of FTA negotiations.

We could argue that the foundations for a re-set are substantial. One-and-a-half million British Indians, only 1.8 per cent of the population, contribute six per cent of Britain’s GDP. British figures place trade at £ 23 billion a year, supporting half a million jobs in each country. Between 2000-2020, Britain is the sixth largest investor in India, with US $28. 21 billion.

But the British media’s flattery (consider “rising superpower”) is like wellness pills, distracting India from building its strength. A nation whose per capita GDP in 2019 was US $ 2,100 can’t be in competition with Britain, whose was US $ 42,329. If Britain refuses to release India from its interventions, it must be because of its hard power. Thus, Niblett has a point that relationships between smaller developed democracies and India are awkward.

India needs to recognise the lack of harmony between different strands of the relationship. Long joint statements and unreachable ambition are not the answer. Arriving at common ground on issues troubling India should be the foremost concern. This relegates Britain’s trade ambitions to secondary importance.

Should India rally British Indians for Indian causes? These are Britons, and this would be involvement in British politics, which will be hard to justify when India objects to British interventions in India’s. A more effective approach is to focus on building comprehensive national power and creating British dependencies. This requires time and patience.

India has drawn down expectations of return of heritage owing to legal hurdles. This remains at the core of India’s grievance politics but as India gains confidence, this issue may have a greater salience in the future.

This relationship has had many beginnings. Just to stay in the game, we have to concede to geopolitics. Britain (post- Brexit) and India (with the China challenge) need partners. Given India’s difficulties amid the pandemic, Britain has early advantage. What will happen after the pandemic? We don’t know.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Jitendra Nath Misra is a former ambassador. He is an Adjunct Professor and Distinguished Fellow in the Jindal School of International Affairs O.P. Jindal Global ...

Read More +