The health shock of COVID 2.0 seems to be seeping into the economic domain and attenuating the pace of our V-shaped recovery. After coping with the first wave of the pandemic, the economy finally showed some signs of recovery from Q3 FY-21. The second COVID-19 wave has now hit the country hard, pushing more than half of the Indian states into lockdown. This brings major headwinds to the economic recovery and downside risks to the possible green shoots.

With this background, it becomes imperative to analyse the incoming economic indicators of India and make sense of where we are headed.

A growth mirage

One needs to be cautious before reading into the economic growth numbers that are reported on a Year-over-Year (YoY) basis, especially those which are reported from March-21 onwards. The low base effect will continue to impact economic data in the coming months and will obscure the true reflection of the Indian economy. YoY-based growth parameters like quarterly GDP figures, Index of Industrial Production (IIP), and external trade would yield stellar, outlier performance for these months, which is why one should read Q1-Q3 FY22 numbers from a different perspective. An alternative approach could be to compare the FY22 numbers with pre-pandemic years.

Industrial performance measured by IIP grew by 22.35 percent in March-21 in comparison to last year. This number is inflated due to the low base, so when the index was compared with the pre-pandemic year, it turns out that IIP showed a contraction of 0.5 percent YoY in March-21 over March-19, reflecting the slowing down of industrial performance. Similarly, merchandise exports grew by 197 percent in April-21 based on a low base. Export performance when compared to the pre-pandemic levels has grown by 16 percent YoY in April-21. This data suggests that though industrial activity slowed due to the domestic headwinds, export growth still firmed up reflecting a steady global demand. Within the domestic economy, the second wave has disproportionately hit the unorganised sector of the economy.

A strong K-shaped trend

The initial months of the first wave had adversely impacted both the organised and the unorganised sector of the economy. However, in subsequent months, the organised sector adapted to the new normal with alacrity, while the unorganised sector, which was limping back to life, has now been served another blow. This idiosyncratic impact of COVID has deepened the dualism between the organised and the unorganised sector; this is also evident from the data which reflects these sectors.

Considering the organised sector—in just four months, India added a dozen startups in the coveted unicorn club. In the capital market, the market capitalisation of listed companies has jumped 60 percent from April-20 to April-21. The GST collections have remained above the one trillion mark for seven consecutive months, hitting an all-time high in April-21. What we observe in India is in line with the global trend where those who are at the top of the economic pyramid have consolidated their wealth. But things have not been so sanguine for those at the middle and the bottom of the pyramid.

In terms of employment, as per Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) survey, the economy was in its worst phase in May-20 with a 24 percent unemployment rate. By January 2021, this figure recovered to around 7 percent. However, in the wake of the second wave of the pandemic and subsequent regional lockdowns, the unemployment rate in May-21 has scaled to 9 percent.

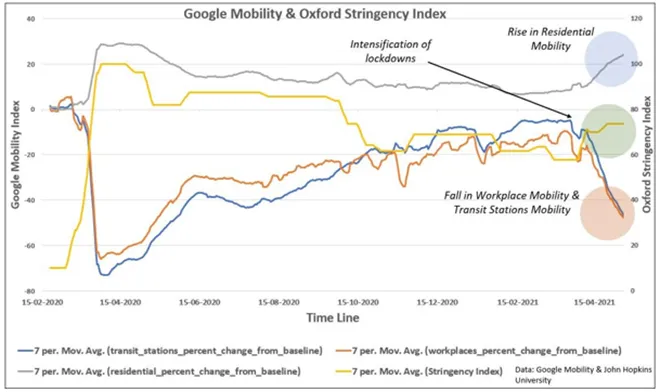

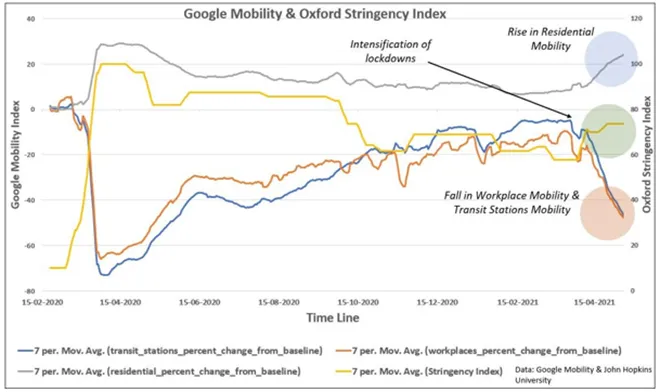

A part of unemployment can be explained by the local movement restrictions put in place by various state governments. Trends in the Google Mobility Index show that the mobility (between third week of March-21 to second week of May-21) to workplace has reduced by around five times, mobility for transit has reduced by a multiple of nine times and residential mobility has increased by a multiple of two-and-a-half times. This finding further correlates with the Oxford Stringency Index, measuring the enforcement of lockdown, which for India has increased from 58 to 74 between March and May-21. These COVID 2.0 induced restrictions will have an impact on income and hence, consumption expenditure as well. Perhaps, this explains the precipitous fall in the CMIE–Urban Consumer Sentiment Index in the month of April-21.

Other high frequency indicators which show possible headwinds to a nascent recovery process are the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) and the E-way bills. While the headline print of PMI manufacturing for the month of April-21 marginally improved to 55.5 from 55.4 in March-21, a slightly deeper dig into this data shows that the PMI held up as there was a faster upturn in international orders. In contrast, the domestic output and sales increased at the slowest rates since last August due to an intensification of the COVID-19 crisis. With the second wave hitting hard and state governments announcing partial lockdowns, the movement of goods and services was impacted adversely. E-way bills for the month of April-21 contracted by 17.5 percent sequentially showing a slowdown in economic activity.

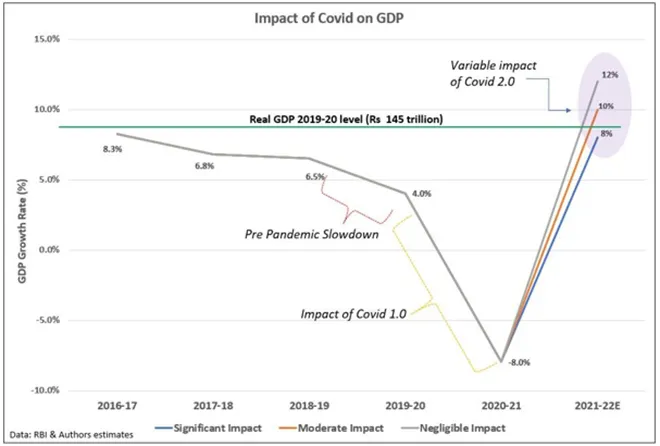

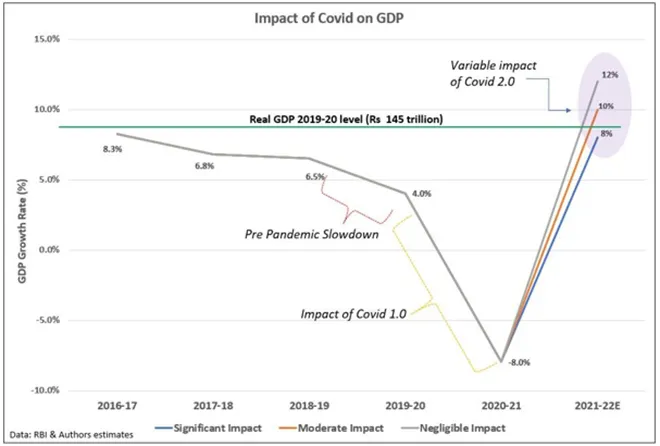

These downside risks are no longer ephemeral and can potentially have a significant impact on our recovery process. Consider this, the economy at the end of FY 20 was at INR 145 trillion (GDP at constant prices). Further, it is estimated that the economy will contract by 8 percent due to the impact of the first wave. Now, with a low base, most forecasters had estimated the economy to grow between 11 percent–13 percent. However, in light of the impact of the second wave, most have revised their forecast to 8–10 percent. What is worth noting is that a sub 8.6 percent performance will leave the economy worse off than it was in March 2020. To overcome these downside risks, the government needs to coordinate its pandemic management strategy—not only with respect to the second wave but also the subsequent ones.

Road to sustainable recovery

Last year, in the absence of a vaccine, the government had to make a binary choice between livelihood versus life. By choosing to protect the latter over the former, the peak of the COVID 1.0 was delayed to the month of September and its intensity was much lower than what most epidemiologists predicted. Our positivity rate—the percentage of all coronavirus tests performed that are actually positive—was around 13 percent at its peak in September 2020. And by January-21, with vaccination options in sight and positivity rate declining to around two percent, we declared victory over the pandemic.

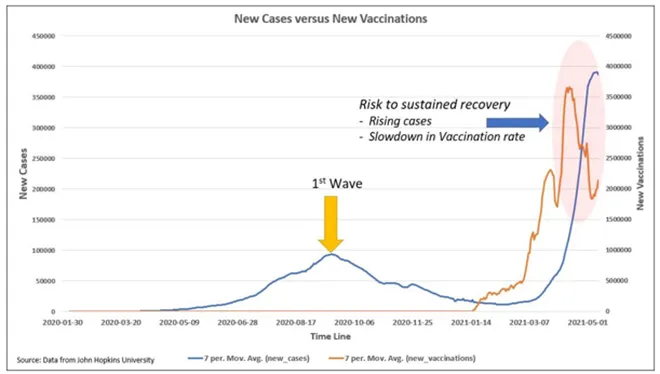

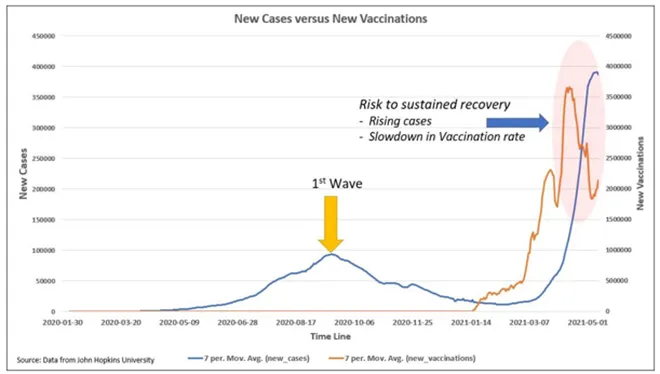

Aided by a virulent mutation, the second wave has struck India with an unanticipated force leading to the crisis that we are in today. However, the national COVID curve seems to have peaked in the first week of May (23 percent positivity rate). Yet, there are two threats which might delay a sustained economic recovery.

The first threat to recovery is the regional pandemic-induced crisis, the kind which we are observing currently in states like Haryana, West Bengal, Karnataka, and Goa—this might lead to further extension of regional lockdowns and, hence, limit the pace of economic recovery. The second threat emanates from the fall in rate of vaccination (seven-day moving average) which has been falling since mid-April-21 due to shortage of vaccine supply. Without inoculating a significant portion of our labour force, the threat of the virus disrupting the real economy is very real, which is apparent from the worldwide experience of multiple COVID waves.

If we have to move forward towards a sustained and real economic growth as against a V-shape or K-shape or a W-shape, it is paramount for the Centre and states to form a cooperative strategy to ramp up the vaccination drive and inoculate the entire adult population in the coming months.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV